Nietzsche and Morality

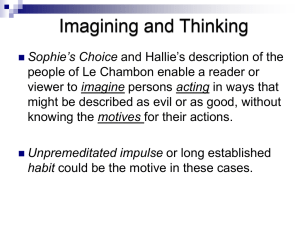

advertisement