The Library of Congress. American Memory. The Learning Page

advertisement

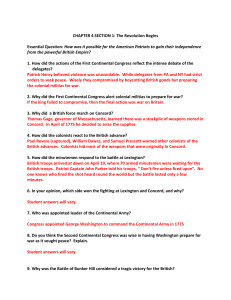

1) The Library of Congress. American Memory. The Learning Page. The American Revolution, 1763-1783. First Shots of War. Depositions Conserning Lexington and Concord, 1775. Deposition of John Parker, 25 April, 1775 John Parker was the captain of the Lexington militia and as such was the commander of the patriots that gathered on Lexington green on the evening of April 18th and the morning of April 19th, 1775. He gave this deposition by order of the Waterford Congress, the illegal Massachusetts colonial assembly that formed after King George III disbanded the Massachusetts assembly. The Waterford Congress had judges take depositions from every Massachusetts resident who had the least amount of information to contribute to what occurred in the battles of Lexington and Concord and delivered these depositions to the Second Continental Congress for their review. In his deposition, Captain Parker swears that he did not order his men to fire, but rather to disperse. He also states that while his men were leaving the green his men were fired upon by the British. 2) The Library of Congress. American Memory. The Learning Page. The American Revolution, 1763-1783. First Shots of War. Depositions Conserning Lexington and Concord, 1775. Diary of an unknown British Officer, 19 April, 1775. This diary from an unnamed British officer states that the British marched onto Lexington green and only engaged the Lexington militia after one or two shots were fired by someone he believed to by a militiaman. The officer also states that the British troops were not ordered to engage the patriots, but rather that the British officers lost control of their soldiers once the first fateful shots were fired. The first paragraph contains all the information about the incident at Lexington green, however the last paragraph offers an interesting insight into what the British officer thought about his mission. He thought it was ill-conceived and poorly executed. 3) The Library of Congress. American Memory. The Learning Page. The American Revolution, 1763-1783. First Shots of War. Depositions Conserning Lexington and Concord, 1775. Deposition of Solomon Brown, Jonathan Loring, Elijah Sanderson, 25 April, 1775. The Deposition of Solomon Brown, Jonathan Loring, Elijah Sanderson is an account of militiamen that were detained by the British army. They were held against their will for no known crime for four hours on the night of April 18th and questioned about the location of the militia weapons stores in Concord. This particular account does not describe the action at Lexington, but gives students background information on what was going on in and around the route from Boston to Lexington. 4) The Library of Congress. American Memory. The Learning Page. The American Revolution, 1763-1783. First Shots of War. Depositions Conserning Lexington and Concord, 1775. Deposition of Elijah Saunderson, 25 April, 1775. The Deposition of Elijah Saunderson is the conclusion to the previous deposition. Elijah Saunderson had previously been detained by British regulars and arrived in Lexington shortly before the action began. He describes a British soldier yelling, “Damn them, we will have them.” This statement is described as causing the British troops to run at the militia and give fire. Elijah Saunderson was a by-standard and not involved in the fighting, but he was a resident of Massachusetts, a colony with a long history of dislike for British soldiers. 5) The Library of Congress. American Memory. The Learning Page. The American Revolution, 1763-1783. First Shots of War. Depositions Conserning Lexington and Concord, 1775. Deposition of Edward Thoroton Gould, Lieutenant in the King's own Regiment of Foot, 25 April, 1775. Edward Thoroton Gould was a British soldier wounded in the fighting at Concord. He was left for dead by the British and nursed back to health by the families of Concord, whose homes his soldiers had just burned down. Edward Thoroton Gould also gave his deposition by order of the Waterford Congress and is the only British account of the events in Lexington that does not say the patriots fired first, but rather that the British troops rushed towards the militia shouting and huzzaing prior to the shots being fired and that he was uncertain of who actually fired first. As an interesting detail to increase student interest, it is worth mentioning that Lt. Gould was shot in the foot at Concord and knocked unconscious by a member of the Concord militia to put him out of his screaming agony. The British would report an exaggerated version of this detail to the people of England in the London Gazette, saying that the patriots had scalped Lt. Gould. 6) The Library of Congress. American Memory. The Learning Page. The American Revolution, 1763-1783. First Shots of War. Depositions Conserning Lexington and Concord, 1775. Deposition of Hannah Bradish, 26 April, 1775. Hannah Bradish was a resident of Menotomy, a town on the road from Boston to Concord. She had given birth to a child the week before and was in bed sleeping in the early morning hours of April 19th, 1775. She did not witness the fighting at Lexington or Concord, but heard the British army and minutemen fighting as the British marched back to Boston. Mrs. Brandish and her children hid in their kitchen as her home was hit by stray bullets from the fighting outside. In her deposition, Mrs. Brandish stated that her home was hit by no fewer than 70 bullets and that the British army looted her home, stealing her clothing and nightgowns. The patriots would exaggerate this questionable deposition and the Boston Gazette would later report that the British soldiers drove women in childbirth from their beds.