A 400 Year History of Scientific Innovation

advertisement

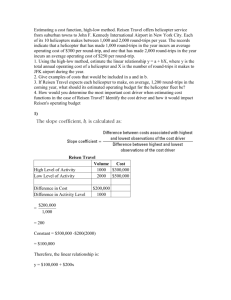

Sean Summers WRIT 340, Warford Illumin Article The Helicopter: A 400 Year History of Scientific Innovation Throughout history, one creation that has seemed to go relatively unnoticed is the helicopter. Undervalued and understudied, the helicopter is a facet of the aerospace industry that has always been overshadowed by the more well-known creation, the airplane. When did this wacky invention come about? What useful purposes did it actually serve? Its 400 year history is a tale of scientific innovation, engineering creativity, and the pursuit of the unknown. 1 THE HUMBLE BEGINNING The helicopter has a history that stretches back centuries. Many historians believe that the idea of a helicopter originated from Milan, Italy, sometime in the 1480’s [1]. Its creator was the philosopher, artist, and scientist, Leonardo Da-Vinci. Da-Vinci had a fascination for inventing flying machines. Many of his machines modeled the flight characteristics of birds, with a flapping motion and wings, called “ornithopters”; however, buried in his hundreds of drawings was one creation that looked nothing like the rest. It was a machine that had a screw-like linen wing structure, which is now Figure 1: Original Drawing of Da-Vinci's Helicopter and a Modern Day Computer Model [3], [9] commonly known as the aerial screw, with a wooden standing platform on the bottom, seen in Figure 1. Da-Vinci proposed that if the spiral was spun fast enough, the machine would Sean Summers WRIT 340, Warford Illumin Article essentially use the momentum of the air it forced downward to lift itself. The idea of the helicopter was born. Though it was never constructed, many models exist today. Da-Vinci’s idea was a radical and creative start; yet, it did have a few flaws. Firstly, the contraption allowed the floor underneath the operators to move. This meant that only half of the power generated by the users would be transmitted to moving the air, while the other half moved the ground underneath them; this is because of Newton’s First Law of Physics, for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. What would later become a concern to engineers, this phenomenon was called torque reaction. The second flaw was that the screw design requires lots of power in order to take flight. As of today, no full size replica has actually been flown. Unfortunately, the helicopter wouldn’t see progress for another 270 years. 2 THE INDUSTRIAL AGE It wasn’t until the Industrial Revolution that the interest in rotary winged aircraft was sparked again. New materials, like metals and plastics, allowed for lighter and more intricate designs. Da Vinci’s idea of an aerial screw had been scrapped and was replaced by a set of rotating wings, called rotors. During the 1700’s, engineers and scientists used spring powered systems in an attempt to master the physics of rotary winged aircraft, countering the torque reaction, as well as keeping the body steady. One such invention is presented in Figure 2. Dating back to 1784, this invention took advantage of a bowdrill system Figure 2: A drawing of Launoy and Bienvenu’s dual rotor model [3] Sean Summers WRIT 340, Warford Illumin Article attached to two rotors of turkey feathers that rotated in opposite directions [1]. It was found that two rotors spinning in opposite directions eliminated their torque reactions, allowing the body to which they were attached to remain steady and in flight. The mechanisms became larger and larger, until the invention of the steam engine brought about the era of full sized crafts. During the 1800’s, the rotary winged aircraft slowly began to evolve and more closely resemble what we consider today to be a helicopter. In fact, the word helicopter was invented during this time, in 1863, when Viscount Gustave de Ponton d'Amécourt from France combined the Greek words helicon and pteron, meaning “spiral” and “wing” [1]. Through decades of bulky and awkward inventions, some large contraptions were able to attain flight by the end of the 19th century, but none with a pilot. It wasn’t until the 1900’s when helicopters gained their success. 3 SUCCESS The first manned rotary winged vehicle to take flight, and what is widely considered to be the first ever helicopter, was flown on November 3, 1907 by French engineer and bicycle maker Paul Cornu [2]. The aircraft, seen in Figure 3, utilized two vertical rotors to compensate for torque reaction and ran on a 24 Figure 3: The Cornu Helicopter (1907), what is considered to be the first helicopter [7] horsepower gasoline engine [3]. However, the flight was only for thirty seconds at one foot off the ground. After this success, development of the helicopter really took off. Only four years later, the first design of a main vertical rotor and a horizontal tail rotor was published (the design many helicopters are based off of today) [1]. Until Sean Summers WRIT 340, Warford Illumin Article this point in history, the full potential of a vertical flight aircraft had never been realized. Engineers had only pursued the idea of a helicopter for their pure love of science and technology. However, what really got helicopters off the ground had a much more malevolent intention. 4 THE MILITARY AGE Soon after the first helicopter was flown, World War I began, which further fueled the research of rotary winged aircrafts. The US military was in need of a vehicle to replace their balloon surveillance craft, and they were looking to the helicopter as a solution. Furthermore, the quality and quantity of building materials, as well as engine technology, were rapidly improving during this time due to the war effort. Though much funding was directed toward the study of helicopters, no successful craft was made during the war. The US Army didn’t have their first helicopter until 1922; it was called the Jerome-de Bothezat Flying Octopus [1]. Though it was much improved from Cornu’s helicopter in 1907, and could sustain flight, it still lacked maneuverability and altitude. From the 1920’s to the 1930’s, fuselages were added to helicopters, and the design of a tail rotor was catching on; the tail rotor was a new adaptation to counter torque reaction. In just a mere 20 years, the first production helicopter was born. The year was 1939, and Igor Sikorsky, who would later be known as the father of helicopters, had invented the VS-300, the world’s first fully controllable helicopter, seen in Figure 5. It utilized the iconic design of a main rotor and tail, and incorporated a powerful 75 horsepower engine [2]. It also was fitted with pontoons, making it the first Figure 4: Sikorsky's VS-300 (1939) [2] Sean Summers WRIT 340, Warford Illumin Article amphibious helicopter as well [1]. The race was now on for the best military helicopter. In 1940, Germany released the Flettner FL 282 Kolibri, which was the first helicopter to be used in combat [1]. It looked much like Sikorsky’s VS-300 and served many roles, like rescue, artillery spotting, and submarine escort. Just three years later, Sikorsky released the R-4, shown in Figure 5, the world’s first helicopter to be mass produced [1]; in 1943, as World War II was underway, the US Army jumped on board, ordering 29 prototypes to be built. The realization of the helicopter’s full potential was now catching on. In 1944, the first combat rescue via Figure 5: Sikorsky's R-4 (1944) [8] helicopter was attempted by U.S. Army Lieutenant Carter Harman in the China-Burma-India theater. He was successful in rescuing three British soldiers. The popularity of the R-4 spread worldwide, as the Royal Air Force had begun purchasing their own. In just ten years, the helicopter had become a highly desired commodity across the globe. It was desired purely for its military applications, and by the end of 1950, fully functioning vehicles were seen in Germany, Canada, the USSR, Britain, France, and the United States. The aviation industry was booming and numerous companies, some of which are still in operation today, were being born: Sikorsky (founded by Igor Sikorsky), Lockheed, Canadair, Mil, and Hughes [3]. The 1950’s saw the invention of the turbine powered helicopter, further powering the rotorcrafts and enhancing their flight capabilities. Their ability to land in hard to reach areas and hover for long durations of time served many purposes outside the military sector. Aircraft could now carry more than one passenger, and fly at speeds up to 190 miles per hour [3]. Sean Summers WRIT 340, Warford Illumin Article The Vietnam War saw the first fully incorporated military action of the helicopter with the Bell UH-1 Iroquois (nicknamed the “Huey”). The iconic helicopter, shown in Figure 6, was used in a wide array of missions, from medical evacuation to bombing runs. However, the helicopter was not yet perfect. During its rise to fame, weapons technology had also evolved; Figure 4: The Bell UH-1 Iroquois "Huey" (1965), serving in Vietnam [8] heavy gun fire and missiles could easily take down the aircraft, and in total 3,305 of the 7,013 UH-1s that served in Vietnam were destroyed [4]. In total 1,074 Huey pilots were killed, along with 1,103 other crew members. The need for an evasive military helicopter was evident [4]. The rise of computer technology was the last development for the helicopter. Computer aided flight controls, night vision, autonomous engine adjustment, and advanced weaponry, all made the helicopter a serious threat from above, as well as a versatile vehicle for other nonmilitary groups. Nearly all modern societies have uses for helicopters: search and rescue, fire control, police enforcement, news footage, an even construction. 5 TODAY The helicopters of today are extremely advanced, highly utilized pieces of machinery. Their uses range from medical evacuation, search and rescue, news reporting, construction, wildlife conservation, and military action. Modern helicopters can reach speeds upwards of 250 miles per hour and can lift payloads of 22 tons [3]. Even more experimental aircrafts are combining the Sean Summers WRIT 340, Warford Illumin Article characteristics of airplanes and helicopters, bringing about a new era in aviation that further pushes the envelope of rotary wing engineering. The idea is to combine the long range and fast flight abilities of the airplane with the vertical takeoff and maneuverability of a helicopter. One such aircraft that has done just that is the Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey, shown in Figure 7 [1]. Known as a “tiltrotor” aircraft, this vehicle takes off with two vertical rotors, but transitions to airplane flight by tilting its rotors forward to become propellers. It has already seen its debut in war efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq and is continuing to prove its mission capabilities. Another development in helicopter design is the incorporation of stealth Figure 5: Bell-Boeing V-22 Osprey (2005), transitioning between vertical and horizontal flight [11] technology. The most current stealth helicopter is the HAL Light Combat Helicopter [5], which features radar absorbent materials, radar deflecting geometries, and noise reduction. The other area of helicopter innovation involves small remote control helicopters that incorporate three or more rotors. Popularly known as “quadrotors,” these small devices are extremely quick and nimble, performing aerial acrobatics never seen before. These small devices can also send video feeds to their controllers. However, unmanned miniature helicopters like these are more than just a hobby for some; they are currently being applied in military surveillance and search and rescue missions. 6 THE FUTURE The future of helicopter aircrafts is far from certain. With technology developing at such a rapid rate, little is known of the capabilities or possible advances that the aerospace industry might see. In a video produced by the US Army titled Aviation 2050 Vision – Technology for Tactics, a sci-fi like future is projected for rotorcraft. The video claims, "Future vertical lift Sean Summers WRIT 340, Warford Illumin Article aircraft will fly further, faster, and perform in a wider range of environmental conditions while carrying heavier payloads. Aircraft may be manned or unmanned. Flight operations will be automated, and the pilot will assume more of a mission commander role." It is very likely that the future will see the incorporation of unmanned, jet propelled helicopters, much like the one presented in Figure 8. Larger aircrafts might incorporate more rotors, as seen in the Figure 6: Aviation 2050 Vision - Technology for Tactics (Video) [10] video, to add larger payload capacity. The technology and engineering of helicopters has seen a radical change over its lifetime. Similarly to how Da Vinci’s idea was much unlike the helicopters of the 1900’s, our ideas of helicopters today may be much different than what the future holds. It is likely the current trend of innovation may even lead to solutions we don’t even know we need yet. Sean Summers WRIT 340, Warford Illumin Article 7 REFERENCES [1] "Helicopter History Site," [Online]. Available: http://www.helis.com/pioneers/. [Accessed 6 Feb 2014]. [2] J. Rumerman, "U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission," [Online]. Available: http://www.centennialofflight.net/essay/Rotary/early_20th_century/HE2.htm. [Accessed 4 Feb 2014]. [3] "Aerospaceweb.org," [Online]. Available: http://www.aerospaceweb.org/design/helicopter/history.shtml. [Accessed 29 Jan 2014]. [4] "Vietnam Helicopter Pilots Association," [Online]. Available: http://www.vhpa.org/heliloss.pdf. [5] "Defense Aviation," [Online]. Available: http://www.defenceaviation.com/2010/04/indias-lightcombat-helicopter.html. [Accessed 10 February 2014]. [6] E. Teale, "Planes That Go Straight Up," Popular Science, vol. 126, no. 3, 1935. [7] "Cornu Helicopter," [Online]. Available: http://projetcornu.free.fr/img/PhotoAccueilModifiee.JPG. [8] R. Lemos, "The Helictoper: A Hundred Years of Hovering," WIRED, 12 November 2007. [Online]. Available: http://www.wired.com/science/discoveries/multimedia/2007/11/gallery_helicopter?slide=2&sli deView=2. [Accessed 11 February 2014]. [9] "All Spectrum Electronics," [Online]. Available: http://www.allspectrum.com/store/product_thumb.php?img=images/EDU61002.gif&w=88&h=80. [Accessed 11 February 2014]. [10] Aviation 2050 Vision - Technology for Tactics. [Film]. United States: United States Army, 2013. [11] "Edwards Airforce Base," 26 April 2005. [Online]. Available: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/thumb/3/34/Osprey_firing_flares.jpg/120pxOsprey_firing_flares.jpg. [Accessed 4 February 2014].