SECURITY ISSUES AND VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT OF

ZIGBEE ENABLED HOME AREA NETWORK IMPLEMENTATIONS

A Project

Presented to the faculty of the Department of Computer Science

California State University, Sacramento

Submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of

MASTER OF SCIENCE

in

Computer Science

by

Roger Meyer

SPRING

2012

© 2012

Roger Meyer

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ii

SECURITY ISSUES AND VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT OF

ZIGBEE ENABLED HOME AREA NETWORK IMPLEMENTATIONS

A Project

by

Roger Meyer

Approved by:

__________________________________, Committee Chair

Isaac Ghansah, Ph.D.

__________________________________, Second Reader

Martin Nicholes, Ph.D.

____________________________

Date

iii

Student: Roger Meyer

I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University

format manual, and that this project is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to

be awarded for the project.

__________________________, Graduate Coordinator

Nikrouz Faroughi, Ph.D.

Department of Computer Science

iv

___________________

Date

Abstract

of

SECURITY ISSUES AND VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT OF

ZIGBEE ENABLED HOME AREA NETWORK IMPLEMENTATIONS

by

Roger Meyer

Smart meters are typically equipped with a ZigBee wireless interface. ZigBee enables a

customer to connect intelligent displays (called In-Home Displays, or IHD) wirelessly to

the smart meter to receive real-time energy consumption data. ZigBee gives customers

ways to save energy by connecting a washing machine or a fridge to the utility's current

electricity price feed and adjust their time of use automatically. Although currently all

smart meters have the wireless interface disabled, the utilities are starting to enable it for

pilot users.

However, this new wireless functionality comes with security risks. This project is about

the analysis of security and privacy issues of ZigBee implementations. This involved a

number of steps. First, ZigBee device firmware was modified so that well-known attack

frameworks such as KillerBee and Scapy could be used to do security testing of other

ZigBee devices. Second, Scapy, which is a packet manipulation program, was improved

to support more ZigBee packets. This allows the use of the Python programming

language for fast creation of standard compliant frames and an easy parsing of received

v

frames. This work will help future attack frameworks to build on this existing Scapy

system.

Major contributions of this project are an improved implementation of the

802.15.4/ZigBee layer in Scapy, a command-line tool to generate Matyas-Meyer-Oseas

(MMO) hashes (converts installation codes to preconfigured link keys), and a security

analysis of a closed ZigBee network.

_______________________, Committee Chair

Isaac Ghansah, Ph.D.

_______________________

Date

vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my project advisor Dr. Isaac Ghansah for providing me a wonderful

opportunity to work on this project, which provided a great exposure to the field of Smart

Grid. I thank him for providing all the help, support and necessary resources to complete

the project successfully.

I am also thankful to Dr. Martin Nicholes for his willingness to serve on the committee. I

benefited very much from the professor’s advice. Thank you for helping me and guiding

me through the project.

My special thanks go to Dr. Nikrouz Faroughi, Graduate Coordinator, for his advice

throughout my master degree and for his support and help in making this project possible.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................... vii

List of Tables ............................................................................................................... xi

List of Figures ............................................................................................................. xii

Chapter

1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................1

1.1

The Smart Grid .................................................................................................1

1.2

Smart Meters ....................................................................................................2

1.2.1

Smart Meter communication to the utility ................................................3

1.3

Privacy Issues ...................................................................................................5

1.4

Significance ......................................................................................................5

1.5

Related Work ....................................................................................................6

1.5.1

ZigBee Security Toolsets ..........................................................................7

1.5.2

Home Area Networks (HAN) Security .....................................................7

1.5.3

Smart Grid Security ..................................................................................8

1.5.4

Smart Meter Security ................................................................................9

1.6

Objectives .......................................................................................................10

2. THE 802.15.4 AND ZIGBEE STANDARDS .......................................................11

2.1

IEEE 802.15.4 ................................................................................................11

2.2

ZigBee ............................................................................................................12

2.2.1

ZigBee layers ..........................................................................................13

2.2.2

Technology comparison ..........................................................................14

2.2.3

ZigBee device and node types ................................................................15

2.2.4

ZigBee star and mesh network ................................................................16

2.2.5

ZigBee encryption ...................................................................................17

2.2.6

ZigBee keys ............................................................................................18

viii

2.2.7

ZigBee security challenges .....................................................................20

2.2.8

Smart Energy Profile (SEP) ....................................................................21

3. ZIGBEE DEVICE HARDWARE AND SOFTWARE CONFIGURATION

FOR SECURITY TESTING..................................................................................27

3.1

Atmel RZUSBSTICK.....................................................................................27

3.1.1

3.2

Flashing the RZUSBSTICK firmware ....................................................29

Memsic TelosB...............................................................................................33

3.2.1

Loading the precompiled KillerBee firmware onto TelosB ...................35

3.3

SimpleHomeNet ZOE-MP1 ...........................................................................36

3.4

Telegesis ETRX2USB-IHD ...........................................................................37

3.4.1

Connecting to ETRX2USB-IHD ............................................................38

3.4.2

Using the Telegesis Demo Program on Linux ........................................40

3.4.3

Configuring the Telegesis “mock meter” firmware ................................41

4. ATTACKS AND TOOLS......................................................................................44

4.1

KillerBee ........................................................................................................44

4.2

Scapy ..............................................................................................................45

4.2.1

Implementation of the 802.15.4 and ZigBee layers in Scapy .................46

4.2.2

How to use the Scapy layer implementation...........................................49

4.3

The Installation Code .....................................................................................52

4.4

An analysis of a closed ZigBee network ........................................................54

4.4.1

Communication with Scapy and KillerBee.............................................55

4.4.2

Encryption ...............................................................................................56

4.4.3

Authentication .........................................................................................58

4.4.4

Privacy ....................................................................................................58

4.5

The ZigBee Alliance ......................................................................................59

4.6

Helpful tools ...................................................................................................59

4.7

Source code ....................................................................................................60

5. CONCLUSION ......................................................................................................61

ix

5.1

Which ZigBee device shall it be? ...................................................................62

5.2

Limits of TelosB/RZUSBSTICK Hardware/Software ...................................63

5.3

Future work ....................................................................................................64

References ....................................................................................................................67

x

LIST OF TABLES

Tables

Page

Table 1 Smart meter messages per 24-hour period ........................................................4

Table 2 IEEE 802.15.4 frequency bands .....................................................................12

Table 3 Wireless technology comparison ....................................................................15

Table 4 ZigBee device types ........................................................................................16

Table 5 Security levels available to the NWK, and APS Layers .................................18

Table 6 Security key assignments per cluster ..............................................................24

Table 7 ZOE-MP1 supported ZigBee clusters .............................................................37

Table 8 Telegesis USB stick terminal settings ............................................................39

Table 9 The KillerBee tool set .....................................................................................45

Table 10 Implementation of frames for the Scapy dot15d4 layer ...............................46

Table 11 Format of the MAC sub-layer beacon payload .............................................47

xi

LIST OF FIGURES

Figures

Page

Figure 1 Home Area Network and AMI connection to the utility .................................4

Figure 2 ZigBee layers .................................................................................................14

Figure 3 ZigBee network topologies............................................................................17

Figure 4 ZigBee stack: version 1.x vs. 2.0...................................................................23

Figure 5 Device authentication: association and CBKE ..............................................26

Figure 6 Atmel RZUSBSTICK ....................................................................................28

Figure 7 JTAGICE mkII window Main tab .................................................................30

Figure 8 JTAGICE mkII window Program tab............................................................31

Figure 9 Connecting the Atmel JTAGICE mkII On-Chip Programmer to the

RZUSBSTICK ..............................................................................................32

Figure 10 Memsic TelosB ............................................................................................34

Figure 11 SimpleHomeNet ZOE-MP1 ........................................................................36

Figure 12 Telegesis ETRX2USB-IHD ........................................................................38

Figure 13 Telegesis demo program..............................................................................40

Figure 14 Matyas-Meyer-Oseas (MMO) hash function ..............................................53

xii

1

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1

The Smart Grid

The Smart Grid is the new intelligent network, which produces, delivers and consumes

electricity. A Home Area Network (HAN) is part of a Smart Grid infrastructure. Its

purpose is to enable the communication between a smart meter, devices consuming

electricity (e.g. heating/cooling, lamp, computer) and devices displaying near real-time

energy consumption data to the home user.

In 2004, the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC) ordered all four Californian

investor‐owned utilities (IOUs) to deploy wireless Advanced Metering Infrastructure

(AMI) for both electricity and gas. The purpose of AMI is to allow customers to have a

better control of their energy costs, give operational benefits for the utilities, and advance

the CPUC's policy to expand demand response in the state. Each IOU has been given the

authorization to deploy smart meters throughout their territories. The deployment of

smart meters is expected to be complete by 2012.

Smart meters are reporting the collected near real-time energy data back to the utility

(e.g. PG&E, SMUD) over the AMI where it will be stored and analyzed. This vast

2

amount of data allows fine-grained data mining, gives the utilities important information

to reduce wasted peak capacity, and helps to better control the demand and response.

Smart meters are equipped with wireless technology (ZigBee, IEEE 802.15.4). This

increases the security perimeter significantly compared to traditional wired meters and

requires adequate protection. If transmitted data is tampered with, the implications can

vary from false display of energy consumption to fraudulent charges. Furthermore, as the

smart meters are in constant communication with the utility, there is the potential to

abuse this connection originating at a consumer’s home all the way back to the utility.

Therefore, the protection of this link is essential for the functionality of this critical

infrastructure.

1.2

Smart Meters

Smart meters are a new type of electrical meter that, like the old meters, measure energy

usage. Smart meters, however, send information back to the utility by wireless signal

instead of having a utility meter reader come to the property and manually do the

monthly electric service reading. The new smart meters are replacements for the older

analog electric meters.

Typically, smart meters have two radios installed (see Figure 1): 1) a radio that utilizes

the licensed 902-928 megahertz (MHz) band for connection to a utility (part of the AMI),

3

and 2) a 2.4 gigahertz (GHz) radio to transmit to devices in the customer premises (the

Home Area Network or HAN).

1.2.1

Smart Meter communication to the utility

The smart meters are connected back to the utility over a wireless link. This is called the

Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI). Smart meters are a part of a mesh network at

the neighborhood level to collect and transmit wireless information from all the smart

meters in that area back to a utility. Figure 1 shows how the smart meter connects back to

the utility over the AMI.

The mesh network requires wireless antennas to be located throughout neighborhoods in

close proximity to where smart meters will be placed. This wireless network operates in

the unlicensed 900 MHz band. The antennas are typically connected to a utility over the

existing cellular and data transmission antennas (cell tower antennas). The mesh network

antennas are often utility-pole mounted. This part of the system can spread hundreds of

new wireless antennas throughout neighborhoods.

4

Figure 1 Home Area Network and AMI connection to the utility

According to a document [20] PG&E filed with the California Public Utilities

Commission on November 1, 2011, the typical meter sends out 9,981 signals per day.

The vast majority of those signals (9,600 signals) came from the devices relaying

information from other meters. Only 6 signals are of meter read data (per 24-hour

period). According to tests from Silver Spring Networks, one meter sent out more than

190,000 signals in one day (see Table 1).

Table 1 Smart meter messages per 24-hour period (source PG&E [20])

Messages per 24-hour

period

Message Type

Meter Read Data

Network Management

Time Synch

Mesh Network Message

Management

Average

Maximum

6

15

360

9,600

6

30

360

190,000

5

1.3

Privacy Issues

The Smart Grid has potential privacy issues. The collection and storage of information

requires a strong privacy policy and a strict enforcement. As we have seen in the previous

section, smart meters send messages back to the utility in real-time. This real-time energy

consumption data allows the utility to create detailed consumer profiles and can include

daily habits like when people get up, go to sleep, take a shower or are not at home. In the

wrong hands, this data can be abused and may create physical safety issues through

robberies, for example. To protect the privacy of customers, adequate practices to

safeguard the data at collection time, in transit and at the storage place are required.

1.4

Significance

Smart meters are becoming the standard electricity-metering device in California. With

the current deployment of PG&E's smart meters (15,000 meters with SmartMeter

technology installed daily by PG&E [6]), the SmartMeter system will be rolled out to all

PG&E customers by mid-2012. More (ZigBee enabled) Home Area Network devices will

become available to the end users. This allows, for example, a utility to signal appliances

the periods of critical peak energy usage or highest prices. Then smart grid-enabled

appliances can temporarily reduce power consumption and save consumer’s money by

choosing to work only during times with the lowest rates.

6

Vulnerabilities in those new systems would allow a malicious user to attack smart meters,

gateways, and ZigBee enabled devices. Wireless systems not only simplify the

deployment of remote devices and the transmission of data but also enable a whole

spectrum of security issues that have to be addressed.

A worst-case scenario would be an attacker breaching not only one home’s systems, but

through one smart meter hop on to other smart meters or even the utility itself. As smart

meters are connected to other smart meters through a mesh network, this scenario is not

unrealistic. The electric grid (generation, transmission, distribution) is part of a nation’s

critical infrastructure and therefore has much higher protection needs than other systems

like a common Wireless Local Area Network (WLAN) for home computers.

1.5

Related Work

ZigBee enabled Home Area Networks are a relatively new field as current smart meters

in California have the ZigBee wireless network disabled. It is therefore a new

environment to explore and assess. Nevertheless, the different technologies (ZigBee,

HAN, smart grid, and smart meters) to be used are known and in use today. In the

following four sections, we give an overview about related work in the fields of ZigBee,

Home Area Networks (HAN) Security, Smart Grid Security, and Smart Meter Security.

7

1.5.1

ZigBee Security Toolsets

ZigBee is a relatively new wireless technology, which has not seen a significant amount

of security research. This makes it an interesting topic.

KillerBee [8] is a tool set for exploring and exploiting the security of ZigBee and IEEE

802.15.4 [9] networks. KillerBee feature set includes ZigBee network eavesdropping,

traffic replay, cryptosystem attacks and more. This project used the KillerBee framework

to gain insight into the ZigBee enabled devices and to test their security. See section 4.1

for a detailed description of the KillerBee framework.

Api-do [10] is a project based on the KillerBee tool set. It is the ZigBee/802.15.4 security

research at the Dartmouth Trust Lab [11]. Improvements include support for more radio

devices and jamming.

1.5.2

Home Area Networks (HAN) Security

The security of Home Area Networks (HAN) was a subject of research and several

documents and presentations about requirements and their architecture are available.

Here are two noteworthy papers and one presentation:

In the white paper “Cyber Security Requirements for Business Processes

Involving Home Area Networks (HAN)” [12], Xanthus Consulting International

8

Inc. discusses the security requirements for different interfaces of HAN-based

systems. They provide a checklist for all systems connected to a HAN.

The presentation “Home Area Network (HAN) Security and Architecture” [13] by

R. Eric Robinson from Itron Inc. shows how the general attack process

(reconnaissance, scanning, exploiting, keeping access) applies to the HAN and

ZigBee.

In 2008, UtilityAMI, a collaboration of multiple utilities, published the

“UtilityAMI 2008 Home Area Network System Requirements Specification”

[14]. Its main part is a list of system requirements to enable a successful

functionality of a Home Area Network. The following criteria are covered in the

specification: HAN applications, communications, security, performance, and

operations-maintenance-logistics.

1.5.3

Smart Grid Security

The Smart Grid and its security and privacy implications are topics that are regularly

covered by the media. The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has

prepared Guidelines for Smart Grid Cyber Security which includes high-level security

requirements, an evaluation of privacy issues and other threats [15].

There are entire books written on the topic of Smart Grid Security like “Securing the

Smart Grid: Next Generation Power Grid Security” [16]. Additionally, regulations like

9

[17] by the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) mandate an

“appropriate” level of security awareness training for persons accessing critical cyber

assets in the electric grid.

1.5.4

Smart Meter Security

At the annual Black Hat 2010 security conference, Mike Davis from IOActive showed

how he and his team from the security consulting firm created a simulation in which over

a period of 24 hours about 15,000 out of 22,000 homes had their smart meters taken over

by a worm that could place the device under the control of the worm’s designers [18]. He

exploited a fundamental design flaw in the specific meter model itself. Among other

things, the meter he took over did not have proper data encryption and did not know the

difference between the meter next to it in the network or a device that was intended to

wirelessly upgrade its software.

In another presentation at Black Hat 2010, Jonathan Pollet, founder of Red Tiger

Security, explained that smart meter technology is making the same mistakes again. Old

vulnerabilities have a new impact when considering smart meters. E.g., data enumeration

can tell criminals when somebody is on vacation and when it is thus a good time to rob

somebody’s home. The software in smart meters is vulnerable to old classes of bugs, like

the ping of death [19].

10

1.6

Objectives

The field of ZigBee enabled Home Area Networks is only developing right now and there

has not been a large amount of research to ensure the safe operation of all involved

devices. This project aims to shed some light on the current state of Home Area Network

implementations.

First, the project required the setup of ZigBee test devices. We have replicated known

ZigBee attack devices and frameworks to reproduce known attacks. Current tools like

Scapy were used and improved for the purposes of the analysis. The goal of the

vulnerability assessment was to assure the robustness of the devices, to learn about their

security features and how this technology can be abused so that a secure deployment can

be achieved.

This report is organized as follows. Chapter 2 introduces the IEEE 802.15.4 and ZigBee

standards. Chapter 3 describes the ZigBee equipment we had access to for this project.

Chapter 4 details the attacks and tools we have used including extensions we made to the

tools. Chapter 5 concludes the project, summarizes the security issues, and proposes

future work.

11

Chapter 2

THE 802.15.4 AND ZIGBEE STANDARDS

This chapter lays the foundation knowledge about the core technologies involved in

Home Area Networks. It is important to understand the basic architecture and the

different layers of both standards as ZigBee is built on top of 802.15.4. The architecture

contains four layers: the physical layer, the media access control (MAC) layer, the

network layer, and the application layer. IEEE defines the lower two layers (physical and

MAC) in 802.15.4. The ZigBee Alliance defines the upper two layers (network and

application). The complete architecture is commonly referred to as the ZigBee

architecture. We begin with a short overview of the IEEE 802.15.4 standard and then

delve into security related ZigBee features like device types, encryption and security

keys.

2.1

IEEE 802.15.4

IEEE 802.15.4 is a standard from the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

(IEEE) [23]. It defines the physical layer (PHY) and the media access control layer

(MAC) for low-rate wireless personal area networks (LR-WPANs). The active standard

is 802.15.4-2011 (released in 2011). The previous standards were 802.15.4-2006 and

802.15.4-2003 respectively. Its main goal is to provide a wireless standard for low power,

low cost and low data rate devices (see section 2.2.2 for a technology comparison). The

802.15.4 standard provides the basis for multiple technologies like ZigBee, ISA100.11a,

12

WirelessHART, MiWi, and 6LoWPAN. All those standards have the same PHY and

MAC layers.

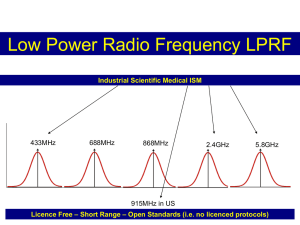

The physical layer can operate in three different frequencies as shown in Table 2:

Table 2 IEEE 802.15.4 frequency bands

Frequency

Where used

Channels

868.0-868.6 MHz

Europe

one communication channel

902-928 MHz

North America

up to thirty channels

2400-2483.5 MHz

worldwide use

up to sixteen channels

The physical layer is responsible for the packet generation, the packet reception, the data

transparency, and the power management. The MAC layer’s responsibilities include

channel acquisition, contention management, NIC address, and error correction. There

are four types of MAC frames: data frames, beacon frames, acknowledgment frames, and

MAC command frames.

2.2

ZigBee

ZigBee is a wireless standard specifically designed for low power, low cost devices. The

ZigBee Alliance [7], a non-profit association, creates the ZigBee standard. ZigBee

operates in the industrial, scientific and medical (ISM) radio bands (2.4 GHz) and is

designed to consume small amounts of power so that devices can have a battery life of

13

several years. There are three different frequency ranges. 868 MHz is used in Europe,

915 MHz is used in the USA and Australia, and 2.4 GHz is used worldwide (see Table 2).

2.2.1

ZigBee layers

ZigBee is built on top of IEEE 802.15.4 (see Figure 2) [9]. Layers one and two, the

physical (PHY) and the media access control (MAC) layers, are defined in the IEEE

standard 802.15.4. The ZigBee Alliance [7] defines the layers above, the network (NWK)

and the application (APS) layers. The application layer consists of ZigBee device objects

(ZDOs) and manufacturer-defined application objects, which allow for customization.

The ZigBee Alliance publishes application profiles like ZigBee Home Automation and

ZigBee Smart Energy to allow different device classes to interoperate. In the Smart Grid

environment, the Smart Energy Profile is used (see 2.2.8).

14

Figure 2 ZigBee layers

2.2.2

Technology comparison

The main goal of ZigBee is to provide a wireless standard for low power devices. Its

competitors are Wi-Fi (802.11), Bluetooth (802.15.1) and GSM/CDMA (the cell phone

network). As can be seen in Table 3, ZigBee’s low power usage is a clear advantage

compared to the other wireless standards. A disadvantage is that it is a relatively new

standard and not yet as widely deployed as the others.

15

Table 3 Wireless technology comparison

ZigBee /

GSM

Wi-Fi / 802.11

802.15.4

Bluetooth /

802.15.1

Sensor Network Wide Area

High Speed

Device

/ Low Power

Voice and Data

Internet

Connectivity

Battery Life

years

1 week

1 week

1 week

Bandwidth

250 Kbps

Up to 2 Mbps

Up to 54 Mbps

720 Kbps

Range

Up to 100

Several

100+ Meters

10-100 Meters

Meters

Kilometers

Low Power,

Existing

Speed,

Convenience

Low Cost

Infrastructure

Ubiquity

Focus

Advantages

2.2.3

ZigBee device and node types

There are two 802.15.4 device types: Full Function Devices (FFD) and Reduced Function

Devices (RFD). An IEEE 802.15.4 network requires at least one FFD to act as a network

coordinator. A RFD needs only a minimum of resources to send or receive data for itself.

ZigBee RFDs are generally battery powered. RFDs can only talk to an FFD, a device

with sufficient system resources for network routing. The FFD can serve as a network

coordinator, or as just another communications device. Any FFD can talk to other FFD

and RFDs. FFDs discover other FFDs and RFDs to establish communications, and they

16

are typically line powered. Table 4 gives an overview of the 802.15.4/ZigBee device

types.

Table 4 ZigBee device types

Coordinator

Network

establishment and

control

Router

Supports routing

functionality; can

talk to other routers,

coordinator, and end

devices

End Device

Can only talk to

routers and the

coordinator

Full Function

Device (FFD):

Requires resources

to handle all

designated tasks.

Yes

Yes

Yes

Reduced Function

Device (RFD):

Requires modest

resources compared

to FFD.

No

No

Yes

A ZigBee network needs exactly one coordinator. The coordinator is responsible for the

Personal Area Network (PAN) setup. The other ZigBee node types, ZigBee routers and

ZigBee end devices, may join a network, but do not form one themselves.

2.2.4

ZigBee star and mesh network

A mesh topology is a type of network where at least some nodes must not only send and

receive their own data, but also serve as a relay for other nodes, that is, they must

collaborate to propagate data in the network. A star network consists of one central

17

coordinator, which acts as a conduit to route messages. A ZigBee network can be a mixed

star and mesh network topology as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3 ZigBee network topologies

2.2.5

ZigBee encryption

ZigBee frames can be optionally protected with the security suite AES-CCM*. This is a

minor variation of AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) with a modified CCM mode

(Counter with CBC-MAC). There are two parts of the protection: encryption and

integrity protection. ZigBee has eight different security levels (see Table 5). For example

18

ZigBee security level 5 in the AES-CCM* suite uses AES 128-bit encryption with a

message integrity code (MIC) length of 4 octets. The bit length of the MIC may take the

values 0, 32, 64 or 128 bits and determines the probability that a random guess of the

MIC would be correct. Table 5 lists the security properties of the security levels.

Table 5 Security levels available to the NWK, and APS Layers (source [22])

Security Level

Identifier

Security Attributes

Data Encryption

Frame Integrity

(length of MIC)

0x00

None

OFF

NO (M = 0)

0x01

MIC-32

OFF

YES (M=4)

0x02

MIC-64

OFF

YES (M=8)

0x03

MIC-128

OFF

YES (M=16)

0x04

ENC

ON

NO (M = 0)

0x05

ENC-MIC-32

ON

YES (M=4)

0x06

ENC-MIC-64

ON

YES (M=8)

0x07

ENC-MIC-128

ON

YES (M=16)

Frames can be protected at the NWK layer, at the APS layer or both at the NWK and

APS layer. Additionally, the MAC layer of 802.15.4 can protect the frame.

2.2.6

ZigBee keys

As explained in the previous section about ZigBee encryption (see 2.2.5), frames can be

protected with encryption and integrity protection. AES-CCM* is a symmetric encryption

19

cipher and therefore requires symmetric keys. There are three kinds of symmetric keys in

ZigBee: network, master, and link keys. All keys have a bit length of 128.

Network key: The network key is shared among all the devices participating in a PAN.

The trust center generates the network key and rotates it at different intervals. Each node

requires the network key in order to join the network. Once the trust center decides to

change the network key, the new one is distributed through the network encrypted with

the old network key. Once this new key is updated in a device, its frame counter is

initialized to zero.

Master key: Master keys form the basis for long-term security between two devices and

are pre-installed in each node. Their function is to keep the link key exchange between

two nodes in the Symmetric-Key Key Establishment procedure (SKKE) confidential.

Link key: Link keys are unique between each pair of nodes and are used to encrypt all

the information between each two devices. They are derived using SKKE. The

application level manages these keys.

Keys can be factory-installed or setup over the air or using out-of-band mechanisms (to

prevent eavesdropping). Link and Network keys can and should be updated periodically.

Additionally, keys can be distributed with the Certificate-Based Key Establishment

protocol (CBKE). CBKE provides a mechanism to negotiate symmetric keys with the

20

Trust Center based on a certificate stored in both devices at manufacturing time and

signed by a Certificate Authority (CA).

2.2.7

ZigBee security challenges

This section briefly discusses the main security challenges for ZigBee devices. These

include the resource constraints of the mobile sensor devices, the small form factor, and

the low cost components.

To pass the ZigBee certification, devices must have a battery life of at least two years.

This low power consumption creates security challenges. Tasks like encryption, key

management, and key exchange are resource intensive and are difficult to achieve with

low power devices. Some mobile devices have very little storage space for keys and

temporary data like security nonces and counters.

Mobile devices are too small to have a display or any input mechanism. Therefore, the

initial key has to be included at manufacturing time. Key provisioning becomes a difficult

and/or cumbersome process if the user has to find a serial number on equipment as big as

a washing machine or as small as a fridge magnet (to display energy price/consumption

for example).

21

For devices to be cheap, they have to be assembled of low cost components that generally

do not have sophisticated security mechanisms to protect them from physical attacks.

Unprotected data or flash memory can be extracted if not protected adequately. The entire

firmware can be copied and analyzed for included cryptographic keys, certificates and

application details. Side channel attacks can be launched to gain information about the

power consumption to derive keys.

2.2.8

Smart Energy Profile (SEP)

The ZigBee Smart Energy Profile Specification [24] is a profile defined by the ZigBee

Alliance. It defines standard practices for Demand Response and Load Management for

“Smart Energy” applications. Because of the type of data and control within the Smart

Energy network, application security is a key requirement. The application will use link

keys, which are optional in the ZigBee and ZigBee Pro stack profiles but are required

within a Smart Energy network. Smart Energy networks will not interact with a consumer

ZigBee Home Area Network unless a device is used to perform an “application level

bridge” between the two profiles or the consumer devices satisfy the Smart Energy

profile security requirements. This is due to the higher security requirements on the Smart

Energy network that are not required on a home network.

Security requirements for the Smart Energy Profile include:

Application link keys are required

22

Preinstalled link keys are installed in each device prior to joining the network

Keys are distributed through an out of band process

Device keys are required to be signed by a Certificate Authority (CA)

The last bullet point implies that a public key infrastructure (PKI) is in place. In practice,

Certicom, a subsidiary of Research In Motion Limited (RIM), is the only ZigBee Smart

Energy certificate authority issuing Elliptic Curve Menezes-Qu-Vanstone (ECMQV)

certificates (see 2.2.8.2 SEP security keys).

2.2.8.1 SEP versions

There are three versions of the Smart Energy Profile: version 1.0, 1.1 and 2.0 (see Figure

4). The latest version 2.0 is still in development and therefore subject to change. Version

1.1 is only a minor update to version 1.0. Version 1.1 includes three new clusters:

tunneling, prepayment and Over-the-Air (OTA) upgrading. In November 2011, PG&E

announced that they will start testing a ZigBee enabled Home Area Network (HAN) with

Control4’s EC-100 In-Home Display in March 2012 [25]. PG&E will use SEP 1.0 for

their HAN implementation initially as the later versions are not yet supported by

manufactured devices [25]. PG&E plans to switch to version 2.0 in the future.

The main addition to Smart Energy (SE) 2.0 is that it is physical layer (PHY) agnostic.

This means that it is designed to run on multiple PHY technologies such as IEEE

23

802.15.4, power line communications, or Wi-Fi. Version 2.0 is also designed to run on

the IP (Internet Protocol) stack, the dominant networking standard. This interoperability

with existing IP-based networks such as Wi-Fi and Ethernet is a key advantage of SEP

2.0. SEP 1.0 only runs over IEEE 802.15.4 radios.

Figure 4 ZigBee stack: version 1.x vs. 2.0

24

Smart meters running SEP 1.0 or 1.1 in meters today can be remotely upgraded to run

SEP 2.0. However, as SEP 2.0 requires more hardware resources, some smart meters

might need to have their circuit boards upgraded, or even be replaced entirely.

2.2.8.2 SEP security keys

The SE Profile requires a higher level of security on the network but not all clusters need

to utilize Application Link keys. Table 6 lists the security keys utilized by each cluster:

Table 6 Security key assignments per cluster (source [24])

Functional Domain

Cluster Name

Security Key

General

Basic

Network Key

General

Identify

Network Key

General

Alarms

Network Key

General

Time

Application Link Key

General

Commissioning

Application Link Key

General

Power Configuration

Network Key

General

Key Establishment

Network Key

Smart Energy

Price

Application Link Key

Smart Energy

Demand Response and Load Control Application Link Key

Smart Energy

Metering

Application Link Key

General

Over the air Bootload Cluster

Application Link Key

Smart Energy

Messaging

Application Link Key

Smart Energy

Tunneling and Generic Tunneling

Application Link Key

Smart Energy

Prepayment

Application Link Key

25

The operation of a device in a Smart Energy network requires the use of a preconfigured

link key, derived from the Installation Code, to join a ZigBee Pro network. The

Installation Code is created randomly during the manufacturing process of each Smart

Energy device. This Installation Code is labeled on the back of the device so that the enduser can read it and provide it to the utility in an out of band process.

After joining the network, a device is required to initiate key establishment using

ECMQV (Elliptic Curve Menezes-Qu-Vanstone) key agreement with the Trust Center, to

obtain a new link key authorized for use in application messages. Prior to updating the

preconfigured link key using key establishment, the Trust Center does not allow Smart

Energy messages that require APS encryption. See Figure 5 for the device authentication

flow in which security keys mentioned in Table 6 are used.

26

Figure 5 Device authentication: association and CBKE

Although the node has a link key, that node has not been authenticated and thus the key's

use is not authorized for application messages. Its use is still required for certain

messages and will be accepted by the trust center.

27

Chapter 3

ZIGBEE DEVICE HARDWARE AND SOFTWARE CONFIGURATION FOR

SECURITY TESTING

This chapter describes the ZigBee hardware devices and software used for this project.

The hardware devices can be classified into two categories. The first category includes

hardware devices that are used to launch our tests and to communicate with ZigBee

devices. The second category contains the ZigBee devices that we tried to test for

security issues. These include ZigBee coordinators, routers and end devices (e.g. smart

plugs, smart meters) as follows.

Atmel RZUSBSTICK

Memsic TelosB

SimpleHomeNet ZOE-MP1: A Metering Smart Plug

Telegesis ETRX2USB-IHD Demo Kit:

o 1 USB stick acting as an In Home Display (IHD)

o 1 USB stick acting as a “mock meter”

3.1

Atmel RZUSBSTICK

The RZUSBSTICK (see Figure 6) is a USB stick manufactured by Atmel with a 2.4GHz

transceiver and a USB connector [2]. RZUSBSTICK was chosen because it is the original

device for which the KillerBee framework was developed (see section 4.1 for a detailed

28

introduction of KillerBee) and it is low priced at $40. The RZUSBSTICK supports the

IEEE 802.15.4 standard and comes with an open-source firmware. The firmware shipped

by Atmel allows the KillerBee framework to use it as a passive sniffer. To be able to

inject packets, the firmware has to be modified. In the following, we describe the process

to flash the default firmware with the modified KillerBee firmware.

Figure 6 Atmel RZUSBSTICK

29

3.1.1

Flashing the RZUSBSTICK firmware

The modified firmware is part of the KillerBee framework. To update the firmware on

the RZUSBSTICK, the following hardware and software is required:

Atmel JTAGICE mkII On-Chip Programmer (hardware, around $300)

Atmel 100-mm to 50-mm JTAG standoff adapter (hardware, around $40)

50-mm male-to-male header (hardware, less than $10)

AVR Studio for Windows (software, free)

The following steps are required to update the firmware:

1. Install AVR Studio on a Windows machine

2. Connect the Atmel JTAGICE mkII On-Chip Programmer via USB to the

Windows machine

3. Download the KillerBee firmware from http://killerbee.googlecode.com. The

firmware file is named kb-rzusbstick-001.hex and is located in the

killerbee/firmware directory.

4. In AVR Studio, click Tools | Program AVR | Connect. From the Platform list,

select JTAGICE mkII, and then click Connect.

5. On the JTAGICE mkII window Main tab (see Figure 7), select AT90USB1287

from the device list. In the Programming Mode and Target Settings group, select

JTAG Mode. Click the Program tab (see Figure 8). In the Flash group, browse to

the path of the KillerBee RZUSBSTICK firmware.

30

Figure 7 JTAGICE mkII window Main tab

6. Connect the RZUSBSTICK to the USB port. The blue LED will light. Using the

JTAG adapter supplied with the JTAGICE mkII, convert to 50-mm pitch with the

JTAG standoff adapter and male-to-male header and insert the pins into the top of

the RZUSBSTICK, holding the pins at a slight angle to provide contact to the

PCB socket. Pin 1 on the JTAGICE mkII JTAG interface should be farthest from

the USB interface on the RZUSBSTICK (see Figure 9).

31

Figure 8 JTAGICE mkII window Program tab

7. With contact between the JTAGICE mkII JTAG interface and the socket on the

RZUSBSTICK, click the Program button in the AVR Studio Programmer. The

Programmer will present status messages as the RZUSBSTICK is programmed:

Reading FLASH input file.. OK

Setting device parameters.. OK!

Entering programming mode.. OK!

Erasing device.. OK!

Programming FLASH ..

OK!

32

Reading FLASH ..

OK!

FLASH contents is equal to file.. OK

Leaving programming mode.. OK!

Figure 9 Connecting the Atmel JTAGICE mkII On-Chip Programmer to the

RZUSBSTICK

If the programming was successful, the amber LED will be lit on the RZUSBSTICK

instead of the blue LED, indicating that the hardware is ready as a KillerBee device. The

device is now ready for all KillerBee features. See [4] for a more detailed description of

the programming process.

33

3.2

Memsic TelosB

The TelosB platform was developed and made available to the research community by

U.C. Berkeley [1]. The device comes with the open-source operating system TinyOS.

TinyOS is a small, open-source, energy-efficient operating system developed by UC

Berkeley that supports sensor networks. The source code and software development tools

are publicly available [3]. It has an integrated onboard antenna, which has an indoor

range of 20 m to 30 m, according to the datasheet. The TelosB has a connector for an

optional external antenna, as seen in Figure 10.

34

Figure 10 Memsic TelosB

The TelosB used for this project, model TPR2420, is built by Memsic Inc. (formerly

XBow) and is a low power device that can run on two AA batteries. As part of the

ZigBee/802.15.4 security research at the Dartmouth Trust Lab [10] [11], the firmware has

been modified to work with KillerBee. The following steps explain how to load the

precompiled firmware image on the TelosB platform.

35

3.2.1

Loading the precompiled KillerBee firmware onto TelosB

The KillerBee framework contains the precompiled firmware for the TelosB platform in

the “killerbee/firmware” directory. The file gf-telosb-001.hex (SHA1

5d85b311b24cc79579cb81651101688b49f38a9e gf-telosb-001.hex) can be loaded on the

TelosB with the following command:

$ ./goodfet.bsl --telosb -e -p gf-telosb-001.hex

MSP430 Bootstrap Loader Version: 1.39-goodfet-8

Mass Erase...

MSP430 Bootstrap Loader Version: 1.39-goodfet-8

Mass Erase...

Transmit default password ...

Invoking BSL...

Transmit default password ...

Current bootstrap loader version: 1.61 (Device ID: f16c)

Changing baudrate to 38400 ...

Program ...

5208 bytes programmed.

Once the firmware is successfully loaded on the device, KillerBee will detect it:

$ zbid

Dev

Product String

/dev/ttyUSB0

Found 1 devices.

Serial Number

GoodFET TelosB/Tmote

36

3.3

SimpleHomeNet ZOE-MP1

The ZOE-MP1 from SimpleHomeNet (Compacta International, Ltd.) is a Smart Energy

metering device in the form of a plug (see Figure 11). It supports the ZigBee Smart

Energy profile and allows controlling appliances with a maximum of 480 Watts. With the

ZOE-MP1, a homeowner can turn on/off the power over the ZigBee network. It acts as a

ZigBee router and therefore is a range extender for other ZigBee devices in the same

PAN. In its function as a metering device, it acts as a server in the Simple Metering

cluster (see Table 7 for a list of supported clusters). This allows other ZigBee devices like

the coordinator to poll the ZOE-MP1 for the consumed energy by its connected

appliance.

Figure 11 SimpleHomeNet ZOE-MP1

37

Table 7 ZOE-MP1 supported ZigBee clusters

Cluster ID

Cluster Name

Client/Server

Cluster Description

0x0000

Basic

Server

Attributes for determining basic

information and setting and enabling

device

0x0003

Identify

Server

Attributes and commands for putting

a device into Identification mode

0x000A

Time

Client

Attributes and commands to interface

to a real-time clock

0x0800

Key

Establishment

Client/Server

Attributes and commands necessary

for managing secure communication

between ZigBee devices

0x0700

Price

Client

Provides mechanism for

communicating electricity pricing

information within the premise

0x0701

Demand

Response and

Load Control

Client

Interface to the functionality of Smart

Energy Demand Response and Load

Control

0x0702

Simple

Metering

Server

Provides mechanism to retrieve

electric power usage

3.4

Telegesis ETRX2USB-IHD

The ETRX2USB-IHD (see Figure 12) is a demo kit from Telegesis Ltd. The demo kit

includes two ZigBee devices in the form of USB sticks:

USB stick with a ZigBee Smart Energy In-Home Display (IHD) firmware

USB stick with a basic “mock meter” firmware

38

The IHD USB can be controlled through AT commands similar to modem commands.

The commands are explained in the document “Smart Energy In-Premise Display AT

Command Manual” [27]. Similarly, the meter USB stick firmware can be controlled

through a Command Line Interface (CLI) described in Ember’s “Application Framework

V2 Developer Guide” [28].

Figure 12 Telegesis ETRX2USB-IHD

3.4.1

Connecting to ETRX2USB-IHD

Both USB sticks offer a simple command line interface. To access the devices, Telegesis

provides their “Terminal PC Software” for Windows only. However, as the commands

are simple terminal commands sent over USB, any terminal emulation program works. In

39

the following, we describe how to configure the program minicom on Linux to connect to

the IHD. Minicom is a popular terminal emulation program that can be installed on

Debian based systems with the command “sudo apt-get install minicom”. Once installed,

it can be either configured in the program itself with a menu-driven help, or by editing

the default configuration file /etc/minicom/minirc.dfl:

pu port

/dev/ttyUSB0

pu baudrate

19200

pu bits

8

pu parity

N

pu stopbits

1

pu rtscts

No

The Telegesis USB sticks require the settings shown in Table 8:

Table 8 Telegesis USB stick terminal settings

Name

Setting

Baudrate (speed)

19200

Bits

8

Parity

N

Stopbits

1

Hardware Flow Control

No

Software Flow Control

No

The devices usually show up as /dev/ttyUSBX on Linux, where X can be any digit. The

first USB device plugged-in will be assigned /dev/ttyUSB0, the second device

/dev/ttyUSB1, and so on. Once the above settings are correct, you can launch minicom

40

with the command “minicom”, or alternatively with “minicom -D /dev/ttyUSB0” to

specify a device on the command line.

3.4.2

Using the Telegesis Demo Program on Linux

Telegesis provides a sample application written in Java to demonstrate the capabilities of

the two USB devices (see Figure 13 for a screenshot of the demo program). The Demo

application allows the configuration of the channel, the PAN ID, the link key and the

network key. It then associates the IHD to the mock meter. The mock meter sends

random energy readings, which are displayed in the Java GUI.

Figure 13 Telegesis demo program

41

The included CD-ROM provides the source code, the compiled class files and a Windows

executable to install and launch the program. We are describing how to use the program

on Linux.

The demo program requires the following two Java libraries:

RXTX: a library for serial and parallel communication (http://rxtx.qbang.org/)

JFreeChart: a chart library (http://www.jfree.org/jfreechart/)

Once the requirements are met, the Java classpath variable has to be set correctly. It has

to include both libraries (RXTX and JFreeChart). Here is an example of how to launch

the demo program:

java -classpath .:jfreechart-1.0.13.jar:jfreechart-1.0.13swt.jar:jcommon-1.0.16.jar DemoMain

If you modified the source code and want to compile it, just replace the java command

with the javac command. The classpath requires the same two libraries for compilation

and for launching the program.

3.4.3

Configuring the Telegesis “mock meter” firmware

The mock meter firmware comes configured with the link key 56 77 77 77 77 77 77 77

77 77 77 77 77 77 77 77 (hexadecimal format, 128 bit), which is the Smart Energy

42

Security Test profile global link key. Although Ember’s “Application Framework V2

Developer Guide” [28] describes the command on how to change this key, the command

fails with error messages. The error message “OUT OF SERIAL CMD BUFFER” means

that the command exceeds the maximum number of command-line arguments. The error

“OUT OF SERIAL CMD SPACE” means that an individual argument is longer than 17

characters.

The work-around is to split up the keys in two parts and remove the spaces in the key so

that the complete command has only 5 arguments. The following sets a link key in the

link key table. The MAC address has to be in reverse order, the key in normal order.

General format:

option link [index in key table decimal or 0x<hex>] [EUI64 in

little endian format in hex without preceding 0x] [key bytes 0-15

in hex without preceding 0x]

Example command:

option link 0 0011223344556677 0011223344556677 8899aabbccddeeff

The complete commands to setup a PAN on the mock meter follows:

# Set the link key (derived from the Installation Code)

option link 0 0011223344556677 0011223344556677 8899aabbccddeeff

# Leave the currently joined ZigBee network

network leave

43

# Start a PAN on channel 15, with power 3 and PAN ID abcd

network form 15 3 abcd

# Enable permit joining on a PAN permanently

network pjoin 0xff

44

Chapter 4

ATTACKS AND TOOLS

This chapter covers the tools we have used and extended. The first tool, KillerBee, is

laying the foundation for attacks on ZigBee networks. Without KillerBee, there is no

open-source and low-cost framework available to sniff and manipulate ZigBee traffic.

Scapy, the second attack tool, allows the creation and parsing of ZigBee packets. We

have extended Scapy to support more ZigBee frames. Next, we provide a utility, which

creates the preconfigured link key from a ZigBee device installation code. We then

describe how these attack frameworks and tools are used in an analysis of a closed

ZigBee network. The last three sections describe issues dealing with the ZigBee Alliance,

list more tools, and show how to access the produced source code.

4.1

KillerBee

KillerBee [8] is a tool set for exploring the security of ZigBee and 802.15.4 networks. It

provides tools to sniff, inject and replay traffic, does packet decoding, and attacks

cryptosystems. See Table 9 for an overview of the tool set provided by KillerBee. Written

in Python, it works well with other Python tools like Scapy (see section 4.2) and fuzzers

like Sulley. The goal of KillerBee is to aid in reconnaissance and exploitation of ZigBee

networks.

45

Table 9 The KillerBee tool set

Tool

Description

zbid

List the available devices supported and plugged-in.

zbdump

A tcpdump-like tool to save sniffed traffic in the libpcap or the

Daintree format.

zbconvert

Convert a capture file format from Daintree SNA files to libpcap

format and vice-versa.

zbreplay

Replay traffic from libpcap or Daintree files.

zbdsniff

Over The Air (OTA) crypto key sniffer: looks through capture

files and searches for cleartext keys.

zbfind

A GUI for ZigBee location tracking.

zbgoodfind

Searches a binary memory dump file (e.g. firmware dump) for

encryption keys.

zbassocflood

ZR/ZC association flooder: Transmit a flood of associate requests

to a target network.

zbstumbler

Search ZigBee controllers. Zbstumbler sends beacon requests on

all channels and listens for beacon frames to identify controllers.

4.2

Scapy

Scapy is a versatile packet manipulation tool written in Python [21]. Its two main features

are mechanisms to create standard compliant packets and to parse received packets into

their fields. Without a tool like Scapy, every packet has to be assembled manually bit by

bit. On the receiving side, every frame has to be parsed individually for the included

fields. Scapy simplifies this process by providing an easy to use interface.

Before Scapy can be used to create and parse IEEE 802.15.4 and ZigBee frames, it has to

be extended to support these new protocols. In Scapy, protocols are called layers. The

46

ZigBee research at Dartmouth [10][11] provided an almost complete implementation of

the 802.15.4 layer (“Dot15d4 layer”). We completed the missing frames of the 802.15.4

layer and added more frames in the ZigBee layer.

4.2.1

Implementation of the 802.15.4 and ZigBee layers in Scapy

The implementation of the frames was done according to the 802.15.4 [23] and ZigBee

[22] specifications. Table 10 shows which frames we have implemented.

Table 10 Implementation of frames for the Scapy dot15d4 layer

Class Name

Description

Dot15d4CmdAssocReq

802.15.4 Association Request Payload

Dot15d4CmdAssocResp

802.15.4 Association Response Payload

Dot15d4CmdDisassociation

802.15.4 Disassociation Notification Payload

Dot15d4CmdGTSReq

802.15.4 GTS request command

ZigBeeBeacon

ZigBee Beacon Payload

LinkStatusEntry

ZigBee Link Status Entry (helper class for

“Link Status Command”)

ZigbeeNWKCommandPayload

Completed all ZigBee Network Layer

Command Frames: "Route request", "Route

reply", "Network Status", "Leave", "Route

Record", "Rejoin request", "Rejoin response",

"Link Status", "Network Report", and

"Network Update"

ZigbeeNWKStub

ZigBee Network Layer for Inter-PAN

Transmission

ZigbeeAppDataPayloadStub

ZigBee Application Layer Data Payload for

Inter-PAN Transmission

ZigbeeClusterLibrary

ZigBee Cluster Library (ZCL) Frame

ZCLReadAttributeStatusRecord

ZCL Read Attribute Status Record

47

We will show how to implement the ZigBee beacon frame as an example. Each frame is

implemented in a Python class. The list of fields is stored in the attribute named

fields_desc. Table 11 shows the formatting of the bit sequence representing the beacon

payload according to the ZigBee specification [22]:

Table 11 Format of the MAC sub-layer beacon payload

Bits:

0-7

Protocol

ID

8-11

12-15

Stack

Nwkc

profile Protocol

Version

16-17

Reserv

ed

18

19-22

Router Device

capacity depth

23

End

Nwk

device

Extcapacity ended

PANId

class ZigBeeBeacon(Packet):

name = "ZigBee Beacon Payload"

fields_desc = [

# Protocol ID (1 octet): bits 0-7

ByteField("proto_id", 0),

# nwkcProtocolVersion (4 bits): bits 12-15

BitField("nwkc_protocol_version", 0, 4),

# Stack profile (4 bits): bits 8-11

BitField("stack_profile", 0, 4),

# End device capacity (1 bit): bit 23

BitField("end_device_capacity", 0, 1),

# Device depth (4 bits): 19-22

BitField("device_depth", 0, 4),

# Router capacity (1 bit): bit 18

BitField("router_capacity", 0, 1),

# Reserved (2 bits): bits 16-17

24-87

88111

Tx

Offset

112119

Nwk

Updat

e ID

48

BitField("reserved", 0, 2),

# Extended PAN ID (8 octets): 24-87

dot15d4AddressField(

"extended_pan_id", 0, adjust=lambda pkt,x: 8

),

# Tx offset (3 bytes): bits 88-111

# In ZigBee 2006 the Tx-Offset is optional, while in the

# 2007 and later versions, the Tx-Offset is a required value.

BitField("tx_offset", 0, 24),

# Update ID (1 octet): bits 112-119

ByteField("update_id", 0),

]

For a correct implementation, each bit/byte must be aligned exactly as in the

specification. The standard network byte order uses the big-endian byte order. Fields that

have less than one octet (8 bits) require special attention. These bit fields must be ordered

with the first byte (lowest address) at the most significant address. This can be seen in the

second octet of the ZigBee beacon frame. The Python implementation first specifies bits

12-15 following bits 8-11. Scapy provides simple data types like BitField and ByteField.

BitField requires three parameters. The first parameter is the name of the field, the second

is the default value, and the last parameter is the bit length of this field. ByteField

requires two parameters, a name and a default value.

49

4.2.2

How to use the Scapy layer implementation

Once the layers are implemented, the application is straightforward. This section will

show how to create ZigBee packets to send a beacon request, associate to a network, and

how to process incoming frames.

4.2.2.1 Creating a ZigBee Beacon Request

If a device wants to join a ZigBee PAN, it first has to find a coordinator. The end device

can do this by sending ZigBee beacon request frames on each channel. If a beacon

request reaches a coordinator or a router, they will reply with a ZigBee beacon frame that

contains all the necessary information for a client device to decide to which PAN it wants

to associate.

In Scapy, a ZigBee beacon requires the Dot15d4 and the Dot15d4Cmd classes:

#!/usr/bin/env python

from killerbee import *

from scapy.all import *

# Beacon Request is part of the Command Frame

b = Dot15d4()/Dot15d4Cmd()

# Destination Addressing Mode set to two (16-bit short address)

b.fcf_destaddrmode = 2

# Source Addressing Mode shall be set to zero

# (source addressing information not present)

b.fcf_srcaddrmode = 0

# Frame Pending subfield shall be set to zero

b.fcf_pending = 0

50

# Acknowledgment Request subfield shall be set to zero

b.fcf_ackreq = 0

b.seqnum = 150 # set the current sequence number

# Destination PAN Identifier shall contain the broadcast PAN ID

b.dest_panid = 0xFFFF

# Destination Address shall contain the broadcast short address

b.dest_addr = 0xFFFF

b.cmd_id = 7 # BeaconReq

kb = KillerBee() # get KillerBee instance

kb.set_channel(11) # set desired channel

kb.inject(str(b)) # send the frame

4.2.2.2 Creating a ZigBee Association Request

Once a device has found a PAN it wants to associate with, the device sends an

association request to the corresponding coordinator/router. The ZigBee specification

additionally requires a data request to be sent to the coordinator/router before the

coordinator replies to the request with an association response frame.

The ZigBee beacon request consists of the Dot15d4, Dot15d4Cmd, and

Dot15d4CmdAssocReq classes:

# Association Request is part of the Command Frame

b = Dot15d4()/Dot15d4Cmd()/Dot15d4CmdAssocReq()

b.fcf_srcaddrmode = 3 # Long addressing mode

# The destination addressing mode shall be set to the same

# mode as in the beacon frame

b.fcf_destaddrmode = 2 # short addressing mode

51

b.fcf_pending = 0

b.fcf_ackreq = 1

b.seqnum = 150

b.dest_panid = 0xABCD # PAN to which to associate

b.dest_addr = 0x0000 # coordinator address

# Source PAN Identifier shall contain the broadcast PAN ID

b.src_panid = 0xFFFF

b.src_addr = 0xCAFEBABECAFEBABE

b.cmd_id = 1 # command ID 1 is the Association Request

4.2.2.3 Receiving and parsing a frame

In this section, we describe how to receive and parse frames with Python, Scapy and

KillerBee. Once a frame has been sent with KillerBee’s inject method, the same

KillerBee instance can be used to receive packets. The code below demonstrates a way to

process incoming packets.

arg_delay = 2 # default delay in seconds to wait for a response

kb = KillerBee() # get KillerBee instance

start = time.time()

pkts = []

# wait for arg_delay seconds to receive answer packets

while (start+arg_delay > time.time()):

pkts.append(kb.pnext()) # append frame to pkts

for recvpkt in pkts:

# Check for empty packet (timeout) and valid FCS

if recvpkt != None and recvpkt[1]:

scapyd = Dot15d4(recvpkt['bytes']) # parse frame

52

# Check if this is a beacon frame

if isinstance(scapyd.payload, Dot15d4Beacon):

src_panid = scapyd.getlayer(Dot15d4Beacon).src_panid

src_addr = scapyd.getlayer(Dot15d4Beacon).src_addr

print "PANID 0x%04X

Source 0x%04X"%(src_panid, src_addr)

# Check if this is a beacon request frame

elif isinstance(scapyd.payload, Dot15d4Cmd):

# Check if this is a beacon request frame

if ( scapyd.getlayer(Dot15d4Cmd).cmd_id == 7 ):

print "Received a Beacon Request"

# Check if this is an association request frame

elif ( scapyd.getlayer(Dot15d4Cmd).cmd_id == 1 ):

print "Received an Association Request"

# Chef if this is a data request frame

elif ( scapyd.getlayer(Dot15d4Cmd).cmd_id == 4 ):

print "Received a Data Request"

4.3

The Installation Code

The installation code is created randomly during the manufacturing process of each smart

energy device. This installation code is labeled on the back of the device so that the enduser can read it and provide it to the utility in an out of band process.

This installation code is required when a smart energy device joins the PAN. After the

association request/response, the trust center (TC) sends the joining device the new link

key, encrypted with the preconfigured link key. This preconfigured link key is derived

from the installation code. After joining the network, a device is required to initiate key

53

establishment using ECMQV (Elliptic Curve Menezes-Qu-Vanstone) key agreement with

the Trust Center, to obtain a new link key authorized for use in application messages.

The preconfigured AES-128 link key is derived from the Installation Code using the

Matyas-Meyer-Oseas (MMO) hash function (specified in Annex B.6 in the ZigBee

Specification [22]). The installation code consists of a 48, 64, 96, or 128-bit number and

a 16-bit CRC (cyclic redundancy check, an error-detecting code). The output is a digest

with a size equal to 128 bits. See Figure 14 for the information flow to create the

preconfigured key from the installation code.

Figure 14 Matyas-Meyer-Oseas (MMO) hash function

54

We have created a command-line tool, which takes the installation code as input and

calculates the link key. The MMO hash function has been adapted from the Wireshark [5]

source code. Here is an example of how to use it:

$ ./mmo 83FED3407A939738c552

IC

= 83FE D340 7A93 9738 C552

MMO = A833 A774 34F3 BFBD 7A7A B979 4214 9287

4.4

An analysis of a closed ZigBee network

We had access to a closed ZigBee network for testing purposes. A closed network means

that only devices from the same vendor are allowed to join the network. Encryption

prevents non-vendor devices from joining and protects the network from eavesdropping.

We used this network to test our Scapy and KillerBee modifications. We also analyzed its

encryption implementation. For security reasons, we will not divulge the identity of the

manufacturer of the devices we used.

The specific network consists of one or more power strips (a block of electrical sockets)

and one coordinator. The power strips act as a router and an end device. This router

functionality creates a mesh network, which is useful if the distance between two power

strips is too large to reach the coordinator. A power strip just needs reachability to one

other power strip which itself then connects to the coordinator (or to the next router).

55

The power strips send power consumption information over the ZigBee network to the

coordinator. The coordinator device has an Ethernet interface, which allows it to connect

to the existing wired network. A web-interface and an Application Programming

Interface (API) on the controller allow one to read the power consumption and to

enable/disable each power socket.

4.4.1

Communication with Scapy and KillerBee

As the complete ZigBee communication is encrypted, possible communication is very

limited. In the following, we describe our efforts in associating to the controller and in

trying to make the power strip associate to our emulated ZigBee controller.

4.4.1.1 Emulate a ZigBee controller

We wrote a basic ZigBee controller to emulate Beacon frames and reply to association

request frames. We used the KillerBee framework to send/receive frames and the Scapy

Dot15d4 layer to create/parse 802.15.4/ZigBee frames.

We were unable to cause the power strip to make an association request to our controller.

The power strip ignored our Beacon frames. It looks like the power strip is looking not

only for the Beacon frames from the controller but also to the regularly sent broadcast

frames that are encrypted and therefore not reproducible.

56

4.4.1.2 Associate to the controller

We were able to associate to the controller with our emulated ZigBee end device written

in Python. Although the controller is sending an “association successful” frame, the

association is not complete until an ACK frame has been sent and received in time by the

controller. Unfortunately, the attacking devices controlled by Python are not fast enough

to generate the ACK frame in time. The controller is sending multiple Association

Response frames because the associating device does not confirm (retransmission after

the timeout). We were therefore unable to successfully associate to the controller and

router.

4.4.2

Encryption

All ZigBee devices (the end devices/routers and the controller) use encryption for their

ZigBee communication. We were looking at how the devices implemented the usage of

the nonce. The cryptographic nonce is an arbitrary number used only once. It is

interesting for two reasons. One, the nonce is a sensitive part in cryptography to generate

non-deterministic ciphertext. A nonce should never be reused within the lifetime of a

single key [26]. This is challenging in mobile and low powered ZigBee devices. This

requires that the nonce be stored on the device while a device sleeps (to save power) or is

shut down. The second reason is that the nonce can be easily analyzed as it is part of the

ZigBee header and therefore has to be sent in cleartext.

57

The most important part of the nonce is the 32-bit frame counter. The frame counter is a

field in the ZigBee frame and protects the message from replaying. This frame counter is

incremented after each frame transmission and hence will at some point wrap to zero.

The ZigBee standard requires that if a device receives a transmission with a frame

counter that is less than or equal to the last received frame counter to discard this frame.

To prevent an eventual lockup where the frame counter on a device reaches the maximum

value (0xFFFFFFFF as the frame counter is a 32-bit field), the network key should be

periodically updated on all devices in the network. This network key update will restore

the frame counter to zero.

We were testing the closed ZigBee network devices to see what happens to the frame

counter if they are shut down and/or reset. It seems like both the power strip and the

controller have local storage where they maintain the current frame counter value. After a

power cycle the counter increases by around 4096. If the power strip loses the association

to its coordinator for a certain amount of time (approximately 4 minutes), it resets its

frame counter to zero and starts a new association.

This power cycle caused the device to reproduce the same ciphertext (CT). When two

different plain texts (PT) are encrypted as CT1 and CT2 using the same key and the same

nonce values, of which CT1 = [PT1 XOR Ekey(nonce)] and CT2 = [PT2 XOR Ekey(nonce)],

an eavesdropper can obtain [PT1 XOR PT2] through computing [CT1 XOR CT2].

58

The comparison of several ciphertexts showed which bytes in the cleartext have changed

and therefore allowed an eavesdropper to make guesses about the plaintext. Here are two

example packets with almost the same ciphertext. The XOR reveals which bytes in the

packets changed in the cleartext:

packet 1:

55 8a 7b e9 1d 61 6c 57 8d bc f1 a1 9d 47 c9 96 59 87 a6 ab f0

packet 2:

55 8a 7b e9 1d 61 6c 30 8d bd f1 a1 9d 47 c9 96 59 87 80 d2 33

packet 1 XOR packet 2:

00 00 00 00 00 00 00 67 00 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 26 79 c3

4.4.3

Authentication

The coordinator device offers two interfaces: a web-interface and an API. Neither uses

encryption nor any form of authentication. It is therefore strongly recommended to

connect the device only to a controlled network that allows some form of authentication.

An intruder with access to the network with this coordinator device can monitor the

power consumption and turn on/off the power sockets at will.

4.4.4

Privacy

The ZigBee coordinator does more than simply give access to the power consumption