6th Grade: Unit 3

1

Supplemental Book

Unit 3

th

6 Grade

6th Grade: Unit 3

DATE

1928

October 24,

1929

2

EVENT

Herbert Hoover elected 31st President of the United States

The stock market crashes.

On a day called "Black Thursday," stock market prices start to drop. The stock market "crashes" when prices

keep dropping and by the end of November, the stock market loses $30 billion.

1930

Hoovers says the worst is over.

President Herbert Hoover tells Americans that the economy will start to improve within the next 60 days. The

Great Depression is actually just getting started.

Severe drought and Dust Bowl conditions began to ruin farmers’ land, a condition that lasted until 1935.

February

1931

Food riots break out in the United States.

Food riots start in cities across the United States. Hungry Americans smash grocery store windows, take food,

and run away because they do not have any other way of getting food to eat.

Workers marched on Detroit, and “foreign workers” were deported.

1932

Roosevelt promises a "new deal."

While campaigning for president of the United States, Franklin Roosevelt promises Americans "a new deal."

The programs he creates after he is elected will be called The New Deal.

Stocks reached their lowest point.

November

1932

Franklin D. Roosevelt elected 32nd President of the United States.

Franklin D. Roosevelt is elected president for the first time. Many Americans did not think that President

Hoover did enough to help them and hope that Roosevelt will end the Depression.

1933

The Emergency Banking Act is passed.

Congress passes the Emergency Banking Act. By the end of the month, almost all of the banks that had closed

when the Depression started are open again.

More than 11,000 of the nation’s 25,000 banks closed.

Roosevelt announced a three-day “bank holiday” to prevent a third run on banks and to shore up the banking

system.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was established to insure bank deposits.

Unemployment reached its highest level, at 25%.

The Civilian Conservation Corps is created.

The first New Deal program, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) is created. Thousands of young men go to

camps to work on projects such as building parks, building roads, and fighting forest fires..

6th Grade: Unit 3

3

The Tennessee Valley Authority is created.

The Tennessee Valley Authority, another New Deal program, brings electricity and jobs to Americans living in

the southern part of the United States.

1935

The Works Progress Administration puts Americans to work.

The Works Progress Administration is created. It puts Americans to work doing many types of jobs such as

writing, acting, building bridges, and building airports.

Social security is created.

The Social Security Act is signed. The Act provides money every month for senior citizens.

1936

Dorothea Lange takes the Migrant Mother photo.

Photographer Dorothea Lange takes photographs of a poor family working at a pea-picking camp in California.

One of the photos, called "Migrant Mother," is one of the most famous photographs to come from the Great

Depression.

FDR was elected to a second term as president.

1937

The economy goes through another recession.

After showing some improvement, the economy starts to suffer again when more Americans lose their jobs.

Many people begin to lose hope that things will ever get better.

1938

FDR asked Congress for an additional $3.75 billion to stimulate the still floundering economy.

1939

The Grapes of Wrath is published.

The book "The Grapes of Wrath" by John Steinbeck is published. The book is about a family that is forced to

leave home and try to find work in California during the Great Depression.

1940

FDR was elected to a third term as president.

December 6,

1941

Japan attacks Pearl Harbor.

Japan bombs American ships at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. Thousands of Americans are killed in the attack.

December 7,

1941

The Great Depression ends.

The United States declares war on Japan and joins World War II. The war creates money and jobs, so the

Great Depression ends soon after the U.S. goes to war.

6th Grade: Unit 3

4

6th Grade: Unit 3

5

Franklin D. Roosevelt Biography

32th President (1933-1945) This information is from the Whitehouse: Presidents of the United

States

Assuming the Presidency at the depth of the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt

helped the American people regain faith in themselves. He brought hope as he promised prompt,

vigorous action, and asserted in his Inaugural Address, "the only thing we have to fear is fear

itself."

Born in 1882 at Hyde Park, New York--now a national historic site--he attended Harvard

University and Columbia Law School. On St. Patrick's Day, 1905, he married Eleanor Roosevelt.

Following the example of his fifth cousin, President Theodore Roosevelt, whom he greatly

admired, Franklin D. Roosevelt entered public service through politics, but as a Democrat. He

won election to the New York Senate in 1910. President Wilson appointed him Assistant

Secretary of the Navy, and he was the Democratic nominee for Vice President in 1920.

In the summer of 1921, when he was 39, disaster hit - he was stricken with poliomyelitis.

Demonstrating indomitable courage, he fought to regain the use of his legs, particularly through

swimming. At the 1924 Democratic Convention he dramatically appeared on crutches to

nominate Alfred E. Smith as "the Happy Warrior." In 1928 Roosevelt became Governor of New

York.

He was elected President in November 1932, to the first of four terms. By March there

were 13,000,000 unemployed, and almost every bank was closed. In his first "hundred days," he

proposed, and Congress enacted, a sweeping program to bring recovery to business and

agriculture, relief to the unemployed and to those in danger of losing farms and homes, and

reform, especially through the establishment of the Tennessee Valley Authority.

By 1935 the Nation had achieved some measure of recovery, but businessmen and

bankers were turning more and more against Roosevelt's New Deal program. They feared his

experiments, were appalled because he had taken the Nation off the gold standard and allowed

deficits in the budget, and disliked the concessions to labor. Roosevelt responded with a new

program of reform: Social Security, heavier taxes on the wealthy, new controls over banks and

public utilities, and an enormous work relief program for the unemployed.

In 1936 he was re-elected by a top-heavy margin. Feeling he was armed with a popular

mandate, he sought legislation to enlarge the Supreme Court, which had been invalidating key

New Deal measures. Roosevelt lost the Supreme Court battle, but a revolution in constitutional

law took place. Thereafter the Government could legally regulate the economy.

Roosevelt had pledged the United States to the "good neighbor" policy, transforming the

Monroe Doctrine from a unilateral American manifesto into arrangements for mutual action

against aggressors. He also sought through neutrality legislation to keep the United States out of

the war in Europe, yet at the same time to strengthen nations threatened or attacked. When

6th Grade: Unit 3

6

France fell and England came under siege in 1940, he began to send Great Britain all possible aid

short of actual military involvement.

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Roosevelt directed

organization of the Nation's manpower and resources for global war.

Feeling that the future peace of the world would depend upon relations between the

United States and Russia, he devoted much thought to the planning of a United Nations, in

which, he hoped, international difficulties could be settled.

As the war drew to a close, Roosevelt's health deteriorated, and on April 12, 1945, while

at Warm Springs, Georgia, he died of a cerebral hemorrhage.

6th Grade: Unit 3

7

The Great Depression

Digital History: President Hoover

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3436

When President Herbert Hoover took office, the unemployment rate was 4.4 percent.

When he left office, it was 23.6 percent.

Hoover’s efforts in providing relief during and after World War I saved millions of

Europeans, including Germans and Russians, from starvation and made him an international

hero. Yet little more than a decade later, many of his own countrymen regarded him as a

heartless brute who would provide federal aid for banks but not for hungry Americans.

Hoover was a proponent of "rugged individualism." But he also said, "The trouble with

capitalism is capitalists; they're too damn greedy."

Born into a hardworking Quaker family in Iowa, Hoover was orphaned before he was ten

years old and was sent west to live with relatives. He was admitted to the first class at Stanford

University, mainly because the new institution needed students. He rose quickly from mine

worker to engineer and entrepreneur. He was worth $4 million by the age of 40, and then

devoted himself to public service. He was elected president at the age of 54.

In the speech that closed his successful 1928 presidential campaign, Hoover, a self-made

millionaire, expressed his view that the American system was based on "rugged individualism"

and "self-reliance." Government, which had assumed unprecedented economic powers during

World War I, should, in his view, shrink back to its prewar size and avoid intervening with

business.

During the early days of the Great Depression, Hoover launched the largest public works

projects. Yet, he continued to believe that problems of poverty and unemployment were best left

to "voluntary organization and community service." He feared that federal relief programs would

undermine individual character by making recipients dependent on the government. He did not

recognize that the sheer size of the nation's economic problems had made the concept of "rugged

individualism" meaningless.

The president appealed to industry to keep wages high in order to maintain consumer

purchasing power. Nevertheless, while businesses did maintain wages for skilled workers, it cut

hours and wages for unskilled workers and installed restrictive hiring practices that made it more

difficult for under qualified younger and older workers to get a job. By April 1, 1933, U.S. Steel

did not have a single full-time employee.

6th Grade: Unit 3

8

Many Republicans believed that a protective tariff would rescue the economy by keeping

out foreign goods. The Smoot-Hawley tariff, signed by Hoover in 1930, raised rates but

provoked retaliation from Britain, Canada, France, Germany, and other traditional trading

partners. The United States found it much more difficult to export its products overseas.

Hoover persuaded local and state governments to sharply increase public works spending.

However, the practical effect was to exhaust state and local financial reserves, which led

government, by 1933, to slash unemployment relief programs and to impose sales taxes to cover

their deficits.

Hoover quickly developed a reputation as uncaring. He cut unemployment figures that

reached his desk, eliminating those he thought were only temporarily jobless and not seriously

looking for work. In June 1930, a delegation came to see him to request a federal public works

program. Hoover responded to them by saying, "Gentlemen, you have come sixty days too late.

The Depression is over." He insisted that "nobody is actually starving" and that "the hoboes...are

better fed than they have ever been." He claimed that the vendors selling apples on street corners

had "left their jobs for the more profitable one of selling apples." By 1932, comedians told the

story of Hoover asking the treasury secretary for a nickel so he could call a friend. Mellon

replies, "Here, take a dime and call all your friends."

Hoover was a stubborn man who found it difficult to respond to the problems posed by

the Depression. "There are some principles that cannot be compromised," Hoover remarked in

1936. "Either we shall have a society based upon ordered liberty and the initiative of the

individual, or we shall have a planned society that means dictation no matter what you call it....

There is no half-way ground." He was convinced that the economy would fix itself.

Only toward the end of his term in office did he recognize that the Depression called for

unprecedented governmental action. In 1932, he created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation

(RFC) to help save the banking and railroad systems. Loans offered under the program funded

public works projects and the first federally-supported housing projects. Originally intended to

combat the Depression, the RFC lasted 21 years and was authorized to finance public works

projects, provide loans to farmers and victims of natural disasters, and assist school districts.

When it was abolished in 1953, it had dispersed $40.6 billion. Its functions were taken over by

the Small Business Administration, the Commodity Credit Corporation, and other housing,

community development, and agricultural assistance programs.

Herbert Hoover was not an insensitive man. He was the first president since Theodore Roosevelt

to invite African American dinner guests to the White House. He said that the use of atomic

bombs against Japan "revolts my soul." He played a key role in launching the United Nation's

Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF) and CARE. Despite his staunch anti-communism stand,

he opposed U.S. involvement in Korea and Vietnam.

6th Grade: Unit 3

9

Nevertheless, his reputation was forever clouded by the Depression. A dam that was to carry

Hoover's name was rechristened Boulder Dam. Washington's airfield, which was to be named for

Hoover, was renamed National Airport.

6th Grade: Unit 3

10

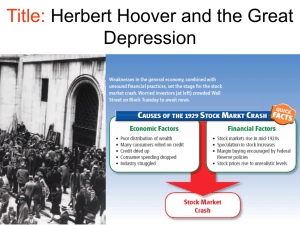

Herbert Hoover and the Depression

Herbert Hoover had the bad luck to be President when the Great Depression started. It

was Hoover who had to come up with the programs to stop the Depression. If he failed, the

whole country would blame him for their trouble. If he succeeded, many Americans would think

he was a great president. You will learn who Hoover was, what he did to end the Depression, and

his reason for thinking his ideas would work.

Who Was Herbert Hoover?

President Herbert Hoover was probably the best prepared and most qualified of the three

presidents of the 1920’s. Born in 1874, he knew poverty from personal experience. His parents

died when he was young, and Hoover was raised by two of his uncles. Since they could not

afford to send him to college so Hoover worked his way through on his own. One of his jobs

took him deep below the ground in a coal mine for $2.50 a day. In school, Stanford University,

he studied engineering. He was such a good mining engineer that he made a million dollars

before he was 40. After that, Hoover thought he had more money than he and his family needed.

He decided to use his great administrative skills for the rest of his working life in government

service and private charity. During World War I, Hoover ran the official U.S. relief agency

helping the suffering people in Belgium. He was called back to the U.S. to head up the Food

Administration under the Democrat, President Woodrow Wilson. His work impressed people so

much that many Democrats wanted him to represent their party in the next Presidential election.

But, Hoover was a Republican and served as a very distinguished Secretary of Commerce under

Presidents Harding and Coolidge.

From his position in the cabinet, Hoover spoke for and carried out the conservative

policies of Presidents Harding and Coolidge. He gained a reputation as a good organizer and

leader, and was a popular choice among Republicans to run for President in 1928. He is much

remembered for his acceptance speech at the Republican National Convention, that the policies

the Republican Party followed the past eight years would soon end poverty in America. Many

Americans believed him and voted him to a landslide victory of 21.4 million votes to 15 million

for the Democrat’s Alfred E. Smith.

President Hoover Faces the Depression

Unfortunately, Hoover did not end poverty in the U.S.A. as he predicted. In fact, he had

to face the worst Depression in American history. The stock market crashed on October 29,

1929, seven months after Hoover became president. The market kept declining for the rest of that

year. Many banks that held bad stocks or made bad loans had to close their doors. Businesses

laid off workers; many closed down completely. Millions of people could not find jobs.

Thousands of homeless people had no place to go, and no one to help them. Although farmers

could not sell surplus crops, hungry people in the cities could not afford to buy food.

6th Grade: Unit 3

11

In facing these problems, Hoover was guided by principles which he believed all his life.

As a student working his way through college, as a successful businessman, and as a leader in

government, Hoover was a firm believer in trickle down and an opponent of government

coercion of any kind. He believed businessmen should be free to pursue their self interest, and

the government should not tell people what to do. He had been taught these ideas in college and

had watched America grow while following them. The fact that he himself had made his fortune

without government help reinforced Hoover’s belief that people should not look for handouts

from their government when they were in trouble.

Hoover's anti-Depression policies were based on his fundamental beliefs, and the theories

advocated by the best economists at the time.

Belief in Volunteerism

Hoover thought the Federal government did not have a right to force people to do

anything. He thought that using the government to solve basic economic problems would do

more to harm America's liberties than it would help its economy. He therefore relied on people’s

good will to do things for others. For instance, when the Depression started, Hoover called

business leaders to meet him in Washington. He then asked them to keep up production and not

to lay off workers or cut wages. He asked neighbors to help one another and not rely on

government aid. He thought that people would act on their own in a fundamentally altruistic way

to end the Depression.

Looking at the Sunny Side

President Hoover believed that it was necessary to maintain a positive outlook. He

thought there was nothing fundamentally wrong with the American economy. All that was

needed Hoover thought was to restore peoples’ confidence in the economy. Once Americans

regained their confidence, Hoover believed, stock prices would rise, factories would open, and

people would go back to work.

Hoover made many optimistic statements. He told the people that there was nothing

basically wrong with the economy. He told them the Depression was a recession and would soon

be over. He repeatedly stated his belief that prosperity was just around the corner.

Saving Business

Voluntarism and optimism failed to stem the tide of business collapse. Unwilling to

follow laissez-faire, Hoover now asked Congress at least to save the major economic institutions

of the land, the banks, insurance companies, railroads, etc. Congress responded by establishing

the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, and Hoover later defended this departure from laissezfaire:

Disaster has been averted in the saving of more than 5,000 institutions and the knowledge that

the adequate assistance was available to tide others over the stress. This was done not to save a

few stockholders, but to save 25,000,000 of American families, every one of whose very savings

6th Grade: Unit 3

12

and employment might have been wiped out and whose whole future would have been blighted

had those institutions gone down.

No Relief

While Hoover broke precedent to spend $2 billion to save banks and railroads from

collapse, he was unwilling to spend any federal money for direct relief. Once the federal

government accepted the responsibility of helping America’s unemployed, Hoover reasoned,

neighbors, communities, cities, and states that had been shouldering this burden would no longer

feel obligated to help. Thus government aid would destroy the feeling of neighborly cooperation

and self-help so fundamental to the American way of life. Belief in these principles rather than

cruelty or indifference to suffering led Hoover to approve a measure providing $45 million to

save cattle in Arkansas but oppose a $25 million grant to save Arkansas farmers. As late as May,

1932, Hoover vetoed a public works bill that would have provided thousands of jobs throughout

the country.

Balance the Budget

Behind Hoover’s reluctance to spend federal dollars on the unemployed lay his belief in

the need to keep the budget balanced. A deficit in the budget could only be met with more taxes

and more federal bond issues. That makes balancing the budget hopeless. The country also

understands that an unbalanced budget means the loss of confidence of our people in the credit

and stability of the government and that the consequences are national demoralization and the

loss of ten times as many jobs as would be created by this program. Hoover had two more

reasons for balancing the budget. He did not think it was fair for people to run a debt that their

children and grandchildren would have to pay back. He also believed if the government kept on

borrowing money it would be much harder for businesses to borrow and start producing again.

Trickle Down

Hoover’s concern with balancing the budget, saving financial institutions, opposing

relief, and restoring business confidence were part of his philosophy that revival of prosperity

depended primarily on business recovery. His policies were directed at helping business.

Prosperity, Hoover believed, trickles down from business men to the public at large. The major

job of government, Hoover once said, “was to bring about a condition of affairs favorable to the

beneficial development of private enterprise.” This had also been the philosophy which had

governed the policy makers of the 1920’s, and which at that time was widely accepted by the

American people. It is your task here to decide whether the policies which flow from this

philosophy are adequate to deal with the problems of the 1930’s.

6th Grade: Unit 3

13

The Human Toll

After more than half a century, images of the Great Depression remain firmly etched in

the American psyche: breadlines, soup kitchens, tin-can shanties and tar-paper shacks known as

"Hoovervilles," penniless men and women selling apples on street corners, and gray battalions of

Arkies and Okies packed into Model A Fords heading to California.

The collapse was staggering in its dimensions. Unemployment jumped from less than 3

million in 1929 to 4 million in 1930, to 8 million in 1931, and to 12 1/2 million in 1932. In that

year, a quarter of the nation's families did not have a single employed wage earner. Even those

fortunate enough to have jobs suffered drastic pay cuts and reductions in working hours. Only

one company in ten failed to cut pay, and in 1932, three-quarters of all workers were on parttime schedules, averaging just 60 percent of the normal work week.

The economic collapse was terrifying in its scope and impact. By 1933, average family

income had tumbled 40 percent, from $2,300 in 1929 to just $1,500 four years later. In the

Pennsylvania coal fields, three or four families crowded together in one-room shacks and lived

on wild weeds. In Arkansas, families were found inhabiting caves. In Oakland, California, whole

families lived in sewer pipes.

Vagrancy shot up as many families were evicted from their homes for nonpayment of

rent. The Southern Pacific Railroad boasted that it threw 683,000 vagrants off its trains in 1931.

Free public flophouses and missions in Los Angeles provided beds for 200,000 of the uprooted.

To save money, families neglected medical and dental care. Many families sought to

cope by planting gardens, canning food, buying used bread, and using cardboard and cotton for

shoe soles. Despite a steep decline in food prices, many families did without milk or meat. In

New York City, milk consumption declined by a million gallons a day.

President Herbert Hoover declared, "Nobody is actually starving. The hoboes are better

fed than they have ever been." But in New York City in 1931, there were 20 known cases of

starvation; in 1934, there were 110 deaths caused by hunger. There were so many accounts of

people starving in New York that the West African nation of Cameroon sent $3.77 in relief.

The Depression had a powerful impact on families. It forced couples to delay marriage

and drove the birthrate below the replacement level for the first time in American history. The

divorce rate fell, for the simple fact that many couples could not afford to maintain separate

households or to pay legal fees. Still, rates of desertion soared. By 1940, there were 1.5 million

married women living apart from their husbands. More than 200,000 vagrant children wandered

the country as a result of the break-up of their families.

The Depression inflicted a heavy psychological toll on jobless men. With no wages to

punctuate their ability, many men lost power as primary decision makers. Large numbers of men

lost self-respect, became immobilized and stopped looking for work, while others turned to

alcohol or became self-destructive or abusive to their families.

In contrast to men, many women saw their status rise during the Depression. To

supplement the family income, married women entered the work force in large numbers.

6th Grade: Unit 3

14

Although most women worked in menial occupations, the fact that they were employed and

bringing home paychecks elevated their position within the family and gave them a say in family

decisions.

Despite the hardships it inflicted, the Great Depression drew some families closer

together. As one observer noted: "Many a family has lost its automobile and found its soul."

Families had to devise strategies for getting through hard times because their survival depended

on it. They pooled their incomes, moved in with relatives in order to cut expenses, bought dayold bread, and did without. Many families drew comfort from their religion, sustained by the

hope things would turn out well in the end; others placed their faith in themselves, in their own

dogged determination to survive that so impressed observers like Woody Guthrie. Many

Americans, however, no longer believed that the problems could be solved by people acting

alone or through voluntary associations. Increasingly, they looked to the federal government for

help.

Copyright 2012 Digital History

6th Grade: Unit 3

15

The Effects of the Great Depression on the People: Unemployment

No economic crisis in American history had been as severe as the Great Depression. It

began in October 1929 in New York City at the time of the stock market crash. With the

population of the United States at about 125 million, in 1929 fewer than two million were

unemployed countrywide; in 1930, eight million had no jobs; in 1931, thirteen million were

without work. The jobless rate would peak in 1932-33 at sixteen million men, or about one third

of the national labor force, as the economic crisis rippled from banking to manufacturing.

Construction all but stopped. Even established industries, like railroads and publishing,

failed. Many unskilled laborers were turned out of work; many white-color workers fell into the

ranks of the unemployed masses; and the professional class was also hit by this tragedy. One out

of three Brooklyn doctors went out of business. Six out of seven architects had to find other

means of employment to support themselves and their families.

The newly rich returned the shiny new motorcars they’d bought on credit and the

working poor were evicted. Everyone knew someone who had lost his livelihood. Some men,

embarrassed that they no longer heard work, pretended they still did. They left their houses in

the morning dressed up in suits, briefcases empty.

Unemployment also hit the farmers. In the Midwest, an area well known for farming, the

people suffered major losses due to unpredicted change in the weather. In the summer of 1931,

crops withered and died. There had always been strong winds and dust on the Plains, but now

over plowing created conditions for disaster. The land became parched, the winds picked up- and

the dust storm began. They rolled in without warning, blotting out the sun and casting entire

towns into darkness. Afterward, there was dust everywhere- in food, in water, in the lungs of

animals and people. Farmers packed up, left their land, and moved westward.

Excerpt from PBS Kids website:

http://www/pbs.org/wnet/newyork/laic/episode6/topic1/e6_tl_sl-ec.html

http://www.pbs.org

6th Grade: Unit 3

16

“Blocks for Tots: A Short History of a Single Family Business”

After he came home from World War I, Mr. Frank Connors went into business for

himself. Using money he saved during the War, he started a toy company that made small

building blocks for children ages 3-5. He called his company, Blocks for Tots. Business was

good right from the start. Connors was making substantial profits which he used to buy more

efficient machines. This helped him keep labor costs low and profits high. While doubling

production, he was able to reduce his work force from 15 workers to 11. Though he gradually

increased wages, his profits grew at a much faster pace.

In the later 1920’s, Mr. Connors began to buy stock with his business profits. HE

speculated on stocks that increased in value quickly, and borrowed money (using margin) to buy

more stocks. When the stock market crashed in 1929 the value of his stocks decreased by

%5,000, and Connors was forced to sell them to supply his broker with more margin. He lost

another $2,000 when his bank was forced to close its doors, and what little money he had left

went to pay for the labor saving machinery he could no longer use. Losing all the money he

made in business was more than a little bit upsetting. After all, he had done what everyone said

he should do. He started a business on his own- he built his business up. He put his money in the

stock market which everyone else seemed to be doing too. He made sure to keep enough money

in a safe bank account in case his business went sour.

As bad as things were in 1920, they kept getting worse for Connors. He learned that

workers who don’t’ have jobs do not buy toys for their kids. The toy business became really

slow. There were hardly any new orders, even for Christmas. As much as he hated to do it,

Connors fired five workers and cut the wages of those who stayed. Even with a smaller work

force, Blocks for Tots kept losing money.

At home, Mrs. Connors cut back on the expenses. The family no longer ate meat every

day. They stopped going to the movies twice a week. The children no longer got their allowances

and Mrs. Connors stopped buying new clothes. The children had to wear “hand me downs” from

neighbors.

Despite all his efforts to cut corners, Connors’ business kept losing money, and in

August, 1931, he shut it down. Now unemployed, Connors moved to Richmond, Indiana where

he could live on his wife’s family farm. At least no one would starve. Connors himself was able

to get a low paying job on a government project. His children went to school in Richmond,

instead of Chicago. That was just was well. Chicago had run out of money to pay its teachers and

its schools had closed.

6th Grade: Unit 3

17

Hoovervilles

As the Depression worsened and millions of urban and rural families lost their jobs and

depleted their savings, they also lost their homes. Desperate for shelter, homeless citizens built

shantytowns in and around cities across the nation. These camps came to be called Hoovervilles,

after the president. Democratic National Committee publicity director and longtime newspaper

reporter Charles Michelson (1868-1948) is credited with coining the term, which first appeared

in print in 1930.

Hooverville shanties were constructed of cardboard, tar paper, glass, lumber, tin and

whatever other materials people could salvage. Unemployed masons used cast-off stone and

bricks and in some cases built structures that stood 20 feet high. Most shanties, however, were

distinctly less glamorous: Cardboard-box homes did not last long, and most dwellings were in a

constant state of being rebuilt. Some homes were not buildings at all, but deep holes dug in the

ground with makeshift roofs laid over them to keep out inclement weather. Some of the homeless

found shelter inside empty conduits and water mains.

Retrieved from: http://www.history.com/topics/hoovervilles

© 1996-2013, A&E Television Networks, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

6th Grade: Unit 3

18

Great Depression

Informational Text

Political Cartoons

6th Grade: Unit 3

19

6th Grade: Unit 3

20

Breadlines

Many people lost their jobs, savings, and property. There was no unemployment

insurance. Almost no government relief reached the people during this time. Some people- even

those who had made a fortune in the stock market’s heyday- now struggled simply to survive.

Many stood in bread lines that were as long as city blocks. The men were wedged so tightly

together that no one passing by could squeeze through.

All who stood in bread lines experienced humiliation. But those in the back of the line,

who often didn’t get anything to eat at all, experience much more than humiliation. They

experience hunger, suffering, and fear for the survival of their families. Whenever garbage trucks

came to the dumps near the Hoovervilles, hundreds of women and children would run out to

scavage for food in the freshly dumped refuse. Living in the city made food-gathering harder. In

the countryside they might have had some luck gleaming something to eat, but in larger cities it

was difficult.

Excerpt from PBS Kids: Learning Adventures in Citizenship website:

http://www.pbs.org/wnet/newyork/laic/epidsode6/topic1/e6_tl_s3-hv.html

Breadlines during Depression

During the Great Depression thousands of unemployed residents who could not pay their

rent or mortgages were evicted into the world of public assistance and bread lines. Unable to find

work and seeing that each job they applied for had hundreds of seekers, these shabby,

disillusioned men wandered aimlessly without funds, begging, picking over refuse in city dumps,

and finally getting up the courage to stand and be seen publicly – in a bread line for free food. To

accommodate them, charities, missions, and churches began programs to feed them. Men who

experienced the waiting in line recall the personal shame of asking for a handout, unable to care

for oneself or to provide for others.

Retrieved from: http://blsciblogs.baruch.cuny.edu/his1005spring2011/2011/03/13/bread-linesduring-the-great-depression/

6th Grade: Unit 3

21

Children During Depression

6th Grade: Unit 3

22

Children During Depression

Children’s Letters to the President

During the Great Depression, many children wrote to the president and the first lady for support

and guidance. Here are a number of their letters:

Ten year old Ohio girl

Please help us my mother is sick three year and was in the hospital three month and she came out

but she is not better and my Father is peralised and can not work and we are poor and the

Cumunity fun gives us six dollars an we are six people four children three boy 15, 13, 12, an one

fril 10, and to parents. We have no one to give us a Christmas presents please buy us a stove to

do our cooking and to make good bread.

Please excuse me for not writing it so well because the little girl 10 year old is writing.

Source: Robert S. McElvaine, ed., Down and Out in the Great Depression, 116.

A twelve year old girl

Barboursville, W. Va.

August, 23, 119341

Dear President & Wife;

This is the first time I or Any of my people wrote Any president. And I am here to ask you for

$8.00 to get me a winter coat. This may seem very strange for a girl 12 years old to do but my

father is a poor honest working Laundry man and he works on a percentage a week we have 10

in our family and my father does not have enough money to get him a bottle of Beer. He is a

democrat and did all he could to have you voted. The N.R.A. [National Recovery

Admonistration] is coming along fine. As little as I am I know just as much about depression as a

grown person. I’m 12 years old and am in the 8th grade curly hair Brunette & brown eyes & fair

complexion & weigh 76 lbs. Hoping to hear from you soon I remain your true Democrat

J.A.G.

P.S. We would have loved if Mrs. Roosevelt when she was visiting Logan t come around to our

small town she was only about 60 miles from here.

6th Grade: Unit 3

23

A child in Kansas

Galena, Kansas

February 5, 1936

Mr Mrs Franklin D Roosevelt

Dear sir I am riling you about my Little Brother who sick see if could get you help send him to

some hospital I see in paper where help other Little children I don’t see how could Be any worse

of then my Little Brother is my Little Brother be 5 years old June he cant walk are talk Are he

cant feed his self he suck a Bottle only when mother feed him he just sit propt in chair that is all

the county DR said is just had him took where Be operated he thought get all rite some says he

got Pralizes of Bone some say it from his spine he had Ricket when he Little never grew very

much he had very Big now my dady had got any money send to hospital I thought rite ask you

help send him mamma take up Capper hospital if had money pay way up there.. hate see go

through Life wy he is my dady was in Relif roll Last Year… I am just m years old go stone

school cherkee Gouty Kansas nad out county seat Clombis Kansas and out county Dr name is Dr

H.H.B. Clumbis Kansas if don’t Believe about my Little Brohter you write and ask him… that

reason riling you see help raise money for mamma take him away

Hoping hear from you soon

6th Grade: Unit 3

24

Reader’s Theatre

The Great Depression:

A Child’s View of the Great Depression

Characters

Child 1 (Sarah)

Child 2 (Andy)

Child 3 (Thomas)

Mother

Father

Narrator

NARRATOR:

Today we are going to take a look at how the Great Depression affected

families.

CHILD 1:

I’m hungry.

CHILD 2:

We’re all hungry, Sarah.

CHILD 3:

Why don’t we have any food around here?

CHILD 2:

There’s no money…you know that, Tommy.

CHILD 1:

Why isn’t father working anymore?

CHILD 2:

Look around you. Nobody’s father is working anymore.

CHILD 1:

Why can’t we just take money out of the bank?

CHILD 2:

The banks have closed.

CHILD 3:

Why can’t they open them?

CHILD 2:

Mama said they’re out of money because they made some bad deals.

NARRATOR:

Banks loaned money to businesses and people who couldn’t pay them

back. The banks also invested in the Stock Market, and those stocks lost

their value. When people started losing money, they ‘ran’ to the banks

trying to get their money out. Of course, the banks didn’t have the money

to pay them. Today, banks have insurance so that this kinds of crash can’t

happen again.

MOTHER:

Maybe we should try moving to another part of the country to find work.

6th Grade: Unit 3

25

FATHER:

There’s nothing anywhere. Did you hear about what’s happening to the

farmers? They’re calling it the Dust Bowl because of the drought there.

They’re all moving to California to see if they can find work there.

CHILD 1:

Are we going to have to move?

MOTHER:

I think so, Sarah, because we have no money to pay rent.

CHILD 3:

Where will we go?

FATHER:

I talked to your grandma. We can sleep on the kitchen floor there.

CHILD 1:

The floor? I don’t want to go!

CHILD 2:

All of us on the floor?

MOTHER:

It is better than begin out on the streets like so many other people. Have

you seen those cardboard cities- they call them Hoovervilles- people living

in the streets with just pieces of cardboard over them.

FATHER:

We’re lucky your grandmother said she would take us in.

CHILD 2:

When will we leave?

MOTHER:

We will have to go very soon.

CHILD 3:

What can we take with us?

FATHER:

There isn’t room for us to take anything but the shirts on our backs. Be

grateful we will have a roof over our heads.

CHILD 1:

What about food? Does Grandmother have food for us?

MOTHER:

We will find food. Your father will be able to stand in the bread lines. I

will be able to find sewing work where your grandmother lives. And you

children might be able to find a job in the factory.

FATHER:

I will look for work, too. It’s easier for women and children to find some

jobs because they get paid less. But I won’t sit and do nothing.

6th Grade: Unit 3

26

CHILD 2:

What about school?

MOTHER:

Maybe later, maybe if things change. Right now, we must all find a way to

live.

NARRATOR:

The children who grew up during the Great Depression learned at an early

age about responsibility and finding ways to survive. They grew up very

quickly. How do you think you would have been able to manage during

the Depression?

The End

Retrieved from: http://toolboxforteachers.s3.amazonaws.com/homecourt-site/GreatDepression_Readers-Theater.pdf

6th Grade: Unit 3

27

The Great Depression: Mexican Americans

The depression hit Mexican American families especially hard. Mexican Americans

faced serious opposition from organized labor, which resented competition from Mexican

workers as unemployment rose. Bowing to union pressure, federal, state and local authorities

"repatriated" more than 400,000 people of Mexican descent to prevent them from applying for

relief. Since this group included many United States citizens, the deportations constituted a gross

violation of civil liberties.

Excerpt from the Digital History website

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/learning_history/children_depression/human_meaning.cfm

Digital History: Mexican Americans

In February 1930, in San Antonio, Texas, 5,000 Mexicans and Mexican Americans gathered at

the city’s railroad station to depart the United States for settlement in Mexico. In August, a

special train carried another 2,000 to central Mexico.

Most Americans are familiar with the forced relocation in 1942 of 112,000 Japanese Americans

from the West Coast to internment camps. Far fewer are aware that during the Great Depression,

The Federal Bureau of Immigration (after 1933, the Immigration and Naturalization Service) and

local authorities rounded up Mexican immigrants and naturalized Mexican American citizens

and shipped them to Mexico to reduce relief roles. In a shameful episode, more than 400,000

repatriodos, many of them citizens of the United States by birth, were sent across the U.S.Mexico border from Arizona, California, and Texas. The Mexican-born population in Texas was

reduced by a third. Los Angeles also lost a third of its Mexican population. In Los Angeles, the

only Mexican American student at Occidental College sang a painful farewell song to serenade

departing Mexicans.

Even before the stock market crash, there had been intense pressure from the American

Federation of Labor and municipal governments to reduce the number of Mexican immigrants.

Opposition from local chambers of commerce, economic development associations, and state

farm bureaus stymied efforts to impose an immigration quota, however, rigid enforcement of

existing laws slowed legal entry. In 1928, United States consulates in Mexico began to apply

with unprecedented rigor the literacy test legislated in 1917.

After President Hoover appointed William N. Doak as secretary of labor in 1930, the Bureau of

Immigration launched intensive raids to identify aliens liable for deportation. The secretary

believed that removal of undocumented aliens would reduce relief expenditures and free jobs for

native-born citizens. Altogether, 82,400 were involuntarily deported by the federal government.

Federal efforts were accompanied by city and county pressure to repatriate destitute Mexican

American families. In February 1931, Los Angeles police surrounded and raided a downtown

6th Grade: Unit 3

28

park and detained some 400 adults and children. The threat of unemployment, deportation, and

loss of relief payments led tens of thousands of people to leave the United States.

Still, the New Deal offered Mexican Americans some help. The Farm Security Administration

established camps for migrant farm workers in California, and the CCC and WPA hired

unemployed Mexican Americans on relief jobs. Many, however, did not qualify for relief

assistance because they did not meet residency requirements as migrant workers. Furthermore,

agricultural workers were not eligible for benefits under workers' compensation, Social Security,

and the National Labor Relations Act.

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3448

6th Grade: Unit 3

29

African Americans and the Great Depression

In 1929, the Great Depression devastated the United States. Hard times came to people

throughout the country, especially rural blacks. Cotton prices plunged from eighteen to six cents

a pound. Two thirds of some two million black farmers earned nothing or went into debt.

Hundreds of thousands of sharecroppers left the land for the cities, leaving behind abandoned

fields and homes. Even "Negro jobs" -- jobs traditionally held by blacks, such as busboys,

elevator operators, garbage men, porters, maids, and cooks -- were sought by desperate

unemployed whites. In Atlanta, Georgia, a Klan-like group called the Black Shirts paraded

carrying signs that read, "No jobs for blacks until every white man has a job." In other cities,

people shouted "Blacks back to the cotton fields. City jobs are for white men." And in

Mississippi, where blacks traditionally held certain jobs on trains, several unemployed white

men, seeking train jobs, ambushed and killed the black workers. The only group in the early

years of the Depression that concerned itself with black rights of rural blacks was the Communist

Party. The Party successfully fought to save the lives of the "Scottsboro Boys," nine black youths

falsely charged with rape in Alabama. Eight were sentenced to death. The Communists also

organized interracial unions and demonstrations for relief, jobs, and end to evictions.

Between Roosevelt's election in 1932 and throughout most of his first term, neither the president

nor the Congress paid much attention to the suffering of blacks. The President did not want to

antagonize the Southern Senators who controlled the Senate and who could block his efforts to

end the Depression. By the end of Roosevelt's first term, the president's thinking began to change

thanks, in part, to the efforts of his wife, Eleanor Roosevelt. Mrs. Roosevelt became profoundly

aware of the injustices suffered by African Americans. She began to speak out publicly on behalf

of blacks and against race prejudice. She became a go-between between civil rights activists and

the President. As a result, Roosevelt began to publicly speak out against lynching and granted

influential black leaders such as Mary McLeod Bethune access to the White House; these

advisors were known as the "Black Cabinet." Federal agencies began to open their doors to

blacks, providing jobs, relief, farm subsidies, education, training, and participation in a variety of

federal programs. The United States Supreme Court began to hand down decisions favoring

black challenges to segregation. For the first time since Reconstruction, the federal government

actively supported blacks and made a concerted effort to incorporate them into the mainstream of

American life. Black voters responded to the change of heart of the Roosevelt administration by

switching their political allegiance from the Republican Party to the Democratic. And black

civil-rights organizations began to increase their activity and demands for their rights as citizens

of the United States.

-- Richard Wormser PBS.org

6th Grade: Unit 3

30

The Great Depression: African Americans

Economic hardship and loss visited all sections of the country. One-third of the Harvard class of

1911 confessed that they were hard up, on relief, or dependent on relatives. Doctors and lawyers

saw their incomes fall 40 percent. But no groups suffered more from the depression than African

Americans and Mexican Americans. A year after the stock market crash, 70 percent of

Charleston's black population was unemployed and 75 percent of Memphis's. In Macon County,

Alabama, home of Booker T. Washington's famous Tuskegee Institute, most black families lived

in homes without wooden floors or windows or sewage disposal and subsisted on salt pork,

hominy grits, corn bread, and molasses. Income averaged less than a dollar a day.

Conditions were also distressed in the North. In Chicago, 70 percent of all black families earned

less than a $1,000 a year, far below the poverty line. In Chicago and other large northern cities,

most African Americans lived in "kitchenettes." Six-room apartments, previously rented for $50

a month, were divided into six kitchenettes renting for $32 dollars a month, assuring landlords of

a windfall of an extra $142 a month. Buildings that previously held 60 families now contained

300.

Excerpt from the Digital History website

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/learning_history/children_depression/human_meaning.cfm

Digital History: African Americans and the New Deal

Until the New Deal, blacks had shown their traditional loyalty to the party of Abraham Lincoln

by voting overwhelmingly Republican. By the end of Roosevelt's first administration, however,

one of the most dramatic voter shifts in American history had occurred. In 1936, some 75 percent

of black voters supported the Democrats. Blacks turned to Roosevelt, in part, because his

spending programs gave them a measure of relief from the Depression and, in part, because the

GOP had done little to repay their earlier support.

Still, Roosevelt's record on civil rights was modest at best. Instead of using New Deal programs

to promote civil rights, the administration consistently bowed to discrimination. In order to pass

major New Deal legislation, Roosevelt needed the support of southern Democrats. Time and

time again, he backed away from equal rights to avoid antagonizing southern whites; although,

his wife, Eleanor, did take a public stand in support of civil rights.

Most New Deal programs discriminated against blacks. The NRA, for example, not only offered

whites the first crack at jobs, but authorized separate and lower pay scales for blacks. The

Federal Housing Authority (FHA) refused to guarantee mortgages for blacks who tried to buy in

white neighborhoods, and the CCC maintained segregated camps. Furthermore, the Social

Security Act excluded those job categories blacks traditionally filled.

The story in agriculture was particularly grim. Since 40 percent of all black workers made their

living as sharecroppers and tenant farmers, the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA)

acreage reduction hit blacks hard. White landlords could make more money by leaving land

6th Grade: Unit 3

31

untilled than by putting land back into production. As a result, the AAA's policies forced more

than 100,000 blacks off the land in 1933 and 1934. Even more galling to black leaders, the

president failed to support an anti-lynching bill and a bill to abolish the poll tax. Roosevelt feared

that conservative southern Democrats, who had seniority in Congress and controlled many

committee chairmanships, would block his bills if he tried to fight them on the race question.

Yet, the New Deal did record a few gains in civil rights. Roosevelt named Mary McLeod

Bethune, a black educator, to the advisory committee of the National Youth Administration

(NYA). Thanks to her efforts, blacks received a fair share of NYA funds. The WPA was

colorblind, and blacks in northern cities benefited from its work relief programs. Harold Ickes, a

strong supporter of civil rights who had several blacks on his staff, poured federal funds into

black schools and hospitals in the South. Most blacks appointed to New Deal posts, however,

served in token positions as advisors on black affairs. At best, they achieved a new visibility in

government.

http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3447

6th Grade: Unit 3

32

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE HARLEM RENAISSANCE

The historical roots of the Harlem Renaissance are complex. In part, they lay in the vast

migration of African Americans to northern industrial centers that began early in the century and

increased rapidly as World War I production needs and labor shortages boosted job

opportunities. Some of the reasons why several millions of African Americans migrated to

northern cities:

Basic civil rights were denied African Americans in the South and their lives were

often in danger.

Wages in the South were low and working conditions were poor.

Education possibilities in the South were limited for African Americans.

Opportunities for African Americans to achieve prominence were greater in the

North.

Jobs were growing rapidly in northern factories because of war production (WWI)

The target for the move north for African American artists and intellectuals was often

New York City, where powerful voices for racial pride such as W. E. B. Du Bois, Marcus

Garvey, and James Weldon Johnson were concentrated. By the 1910s, Harlem had become a

spirited community that provided continuity and support for a diverse population pouring in from

the South and the Caribbean.

The Harlem Renaissance is also rooted in the disappointment that African Americans felt

with the limited opportunities open to them as the United States struggled to transform itself

from a rural to an urban society. Increased contact between African Americans and white

Americans in the workplace and on city streets forced a new awareness of the disparity between

the promise of U.S. democracy and its reality. African American soldiers who served in World

War I were angered by the prejudice they often encountered back at home, compared to the

greater acceptance they had found in Europe. A larger, better-educated urban population fully

comprehended the limitations that white-dominated society had placed on them. As African

Americans became increasingly disillusioned about achieving the justice that war-time rhetoric

had seemed to promise, many determined to pursue their goals of equality and success more

aggressively than ever before.

Organized political and economic movements also helped to motivate the Harlem

Renaissance by creating a new sense of empowerment in African Americans. The NAACP

boasted nearly 44,000 members by the end of 1918. In the early 1920s Marcus Garvey’s message

of racial pride drew hundreds of thousands of ordinary men and women to his United Negro

Improvement Association and its Back-to-Africa movement. Other African Americans, including

many intellectuals, turned to socialism or communism. By 1920, large numbers of African

Americans of all political and economic points of view were plainly unwilling to settle for the

old ways any longer. One unexpected development had an impact on the form their demand for

change would take: urbane whites suddenly “took up” New York’s African American

6th Grade: Unit 3

33

community, bestowing patronage on young artists, opening up publishing opportunities, and

pumping cash into Harlem’s “exotic” nightlife in a complex relationship that scholars continue to

probe. Fueled by all of these historical forces, an unprecedented outpouring of writing, music

and visual arts began among African American artists.

http://www.learner.org/courses/amerhistory/pdf/Harlem-Ren_L-One.pdf

The Harlem Renaissance: A Unit of Study for Grades 9-12, Nina Gifford

6th Grade: Unit 3

34

Langston Hughes

A Harlem Renaissance Poet

Langston Hughes was born on February 1, 1902, in Joplin, Missouri. He published his

first poem in 1921 while attending Columbia University. After his poetry was promoted by

prominent figures in the literary world, Hughes published his first book, The Weary Blues, in

1926. The book had popular appeal and established both his poetic style and his commitment to

black themes and heritage. Hughes was also among the first to use jazz rhythms and dialect to

depict the life of urban blacks in his work. He went on to write countless works of poetry, prose

and plays, as well as a popular column for the Chicago Defender. He died on May 22, 1967.

I, Too

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I'll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody'll dare

Say to me,

"Eat in the kitchen,"

Then.

Besides,

They'll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed-I, too, am America.

Langston Hughes

Retrieved from: http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/i-too/

6th Grade: Unit 3

35

1930's Food and Groceries prices

Imagine you could go shopping for food and groceries in the 1930's these are some of the foods you may have

bought to feed a family

These are some of the things you may have seen advertised Below and how much food and

groceries cost in the 30's

Shoulder of Ohio Spring lamb 17 cents per pound Ohio 1932

Sliced Baked Ham 39 cents per pound Ohio 1932

Dozen Eggs 18 Cents Ohio 1932

Coconut Macaroons 27 cents per pound Ohio 1932

Bananas 19 cents for 4 Pounds Ohio 1932

Peanut Butter 23 cents QT Ohio 1932

Bran Flakes 10 cents Maryland 1939

Jumbo Sliced Loaf of Bread 5 cents Maryland 1939

Spinach 5 cents a pound Maryland 1939

Clifton Toilet Tissue 9 cents for 2 rolls Ohio 1932

Camay Soap 6 cents bar Ohio 1932

Cod Liver Oil 44 cents pint Wisconsin 1933

Tooth paste 27 cents Wisconsin 1933

Lux Laundry Soap 22 cents Indiana 1935

Suntan Oil 25 cents Pennsylvania 1938

Talcum Powder 13 cents Maryland 1939

Noxzema Medicated Cream for Pimples 49 cents Texas 1935

Applesauce 20 cents for 3 cans New Jersey

Bacon, 38 cents per pound New Jersey

Bread, white, 8 cents per loaf New Jersey

Ham, 27 cents can New Jersey

Ketchup, 9 cents New Jersey

Lettuce, iceberg, 7 cents head New Jersey

Potatoes, 18 cents for 10 pounds New Jersey

Sugar, 49 cents for 10 pounds New Jersey

Soap, Lifebuoy, 17 cents for 3 bars New Jersey

Sugar $1.25 per 25LB Sack Ohio 1932

Pork and Beans 5 cents can Ohio 1932

Oranges 14 for 25 cents Ohio 1932

Chuck Roast 15 cents per pound Ohio 1932

White Potatoes 19 cents for 10LBs Ohio 1932

Heinz Beans 13 cents for 25oz can Ohio 1932

6th Grade: Unit 3

Spring Chickens 20 cents per pound Ohio 1932

Wieners 8 cents per pound Ohio 1932

Best Steak 22 cents per pound Ohio 1935

Pure lard 15 cents per pound Wisconsin 1935

Hot Cross Buns 16 Cents per dozen Texas 1939

Campbells Tomato Soup 4 cans for 25 cents Indiana 1937

Oranges 2 dozen 25 cents Indiana 1937

Kellogs Corn Flakes 3 Pkgs 25 cents Indiana 1937

Mixed Nuts 19 Cents per pound Indiana 1937

Pork Loin Roast 15 cents per pound Indiana 1937

Channel Cat Fish 28 cents per pound Missouri 1938

Fresh Peas 4 cents per pound Maryland 1939

Cabbage 3 cents per pound Maryland 1939

Sharp Wisconsin Cheese 23 cents per pound Maryland 1939

36

6th Grade: Unit 3

37

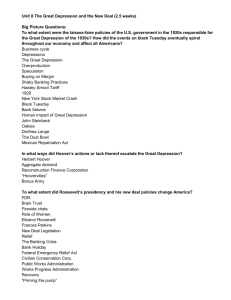

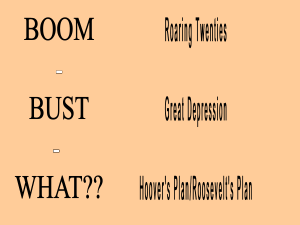

1930s News, Events, Popular Culture and Prices

The Thirties saw the growth of Shanty Towns caused by the Great Depression, Dust Storms, Radical Politics

Around The World, and what many consider an upside down world where bank robbers were seen as hero's

not villains.

Money and Inflation 1930's

To provide an estimate of inflation we have given a guide to the value of $100 US Dollars for the

first year in the decade to the equivalent in today's money.

If you have $100 Converted from 1930 to 2005 it would be equivalent to $1204.42 today "If You

Had 1 billion dollars then it would now be worth 12 billion dollars."

In 1930 average new house cost $7,145.00 and by 1939 was $3,800.00

In 1930 the average income per year was $1,970.00 and by 1939 was $1,730.00

In 1930 a gallon of gas was 10 cents and by 1939 was 10 cents

In 1930 the average cost of new car was $640.00 and by 1939 was $700.00

A few more prices from the 30's and how much things cost

Firestone Tyre 1932 from $3.69 , Single Vision Glasses 1938 $3.85 , Complete Modern 10 piece

bedroom Suite $79.85 , Steak 1938 1LB 20 cents , New Emerson Bedroom Radio 1938 $9.95 ,

Shaefer Pens 1933 from $3.35 , Plymouth Roadking Car 1938 $685 , Emmerson 5 tube bedroom

radio $9.95 , Howard Deluxe Quality silk lined hat $2.85 , Cotton Chiffon Volle Girls Frock

$2.98

Toys 1930s

From Our 1930s

Price: $11.98

Check out the new toys pages where you

can see some of the children's toys that

could be found during the Depression

Years including Balsa Wood Toy Kits,

Flossy Flirt Doll, Electric Train Sets and

more

Chevrolet 1935 Master Deluxe

New Master De luxe Chevrolet with improved

master blue flame engine, pressure steam oiling ,

cable brakes and shock proof steering

$560

Example of a house for sale

1934

Stucco Bungalow

Oakland

California .

5 room stucco bungalow ,

breakfast room , separate

garage, delightful location

$3,750

6th Grade: Unit 3

38

6th Grade: Unit 3

39

Bud, not Buddy

Pre-Reading

Interview Transcripts for video clip titled:

Along for the ride

One of the great joys of writing for me is not knowing where the story is going to go, or even

having a concept of where it's going to go and being told halfway through, "That's not what

happened. This is what happened." I know in the book that I just finished, Elijah of Buxton, I

wrote the last chapter first, and it changed over time. Once I got to know the character, I realized

that things that happened in the chapter as I had written it at first didn't work out, and the story

changed.

I never know where the story's going to go. I never know who's going to be in it. Originally, in

Bud, Not Buddy, I thought that I would tell a story about my grandfather as a ten-year-old boy.

Back during the 1930s, he actually had a band called Herman Curtis and the Dusky Devastators

of the Depression. Thought it was the coolest name in the world. I wanted to write something

about it. Started to write, thinking that the boy would be my grandfather. Turns out it was this

ten-year-old orphan named Bud. My grandfather was in the story, still, but he was a crusty, old

musician.

You never know, and that's one of the real delights of telling a story. It makes you wonder how

many stories are in there that if I would sit down and really apply myself, how many other stories

would come out like that — because it's great entertainment. When I'm writing, I have a lot of

fun. I'm laughing. Some of the time, I'm crying. I'm a real sight to watch when I'm writing.

© Copyright 2013 WETA Washington, D.C.

Reading Rockets is funded by a grant from the U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special

Education Programs

6th Grade: Unit 3

40

Bud, not Buddy

Chapter 2

Brer Rabbit, trickster figure originating in African folklore and transmitted by African slaves to

the New World, where it acquired attributes of similar Native American tricksters. Brer, or

Brother, Rabbit was popularized in the United States in the stories of Joel Chandler Harris

(1848–1908). The character’s adventures embody an idea considered to be a universal creation

among oppressed peoples—that a small, weak, but ingenious force can overcome a larger,

stronger, but dull-witted power. Brer Rabbit continually outsmarts his bigger animal associates,

Brer Fox, Brer Wolf, and Brer Bear.

6th Grade: Unit 3

41

Bud, not Buddy

Chapter 2

Brer Rabbit and the Tar Baby

A Georgia Folktale

retold by S.E. Schlosser

Well now, that rascal Brer Fox hated Brer Rabbit on account of he was always cutting

capers and bossing everyone around. So Brer Fox decided to capture and kill Brer Rabbit if it

was the last thing he ever did! He thought and he thought until he came up with a plan. He would

make a tar baby! Brer Fox went and got some tar and he mixed it with some turpentine and he

sculpted it into the figure of a cute little baby. Then he stuck a hat on the Tar Baby and sat her in

the middle of the road.

Brer Fox hid himself in the bushes near the road and he waited and waited for Brer

Rabbit to come along. At long last, he heard someone whistling and chuckling to himself, and he

knew that Brer Rabbit was coming up over the hill. As he reached the top, Brer Rabbit spotted

the cute little Tar Baby. Brer Rabbit was surprised. He stopped and stared at this strange

creature. He had never seen anything like it before!

"Good Morning," said Brer Rabbit, doffing his hat. "Nice weather we're having." The Tar

Baby said nothing. Brer Fox laid low and grinned an evil grin.

Brer Rabbit tried again. "And how are you feeling this fine day?" The Tar Baby, she said

nothing. Brer Fox grinned an evil grin and lay low in the bushes. Brer Rabbit frowned. This

strange creature was not very polite. It was beginning to make him mad.

"Ahem!" said Brer Rabbit loudly, wondering if the Tar Baby were deaf. "I said 'HOW

ARE YOU THIS MORNING?" The Tar Baby said nothing. Brer Fox curled up into a ball to

hide his laugher. His plan was working perfectly!

"Are you deaf or just rude?" demanded Brer Rabbit, losing his temper. "I can't stand folks

that are stuck up! You take off that hat and say 'Howdy-do' or I'm going to give you such a

lickin'!" The Tar Baby just sat in the middle of the road looking as cute as a button and saying

nothing at all. Brer Fox rolled over and over under the bushes, fit to bust because he didn't dare

laugh out loud.

"I'll learn ya!" Brer Rabbit yelled. He took a swing at the cute little Tar Baby and his paw

got stuck in the tar.

"Lemme go or I'll hit you again," shouted Brer Rabbit. The Tar Baby, she said nothing.

"Fine! Be that way," said Brer Rabbit, swinging at the Tar Baby with his free paw. Now

both his paws were stuck in the tar, and Brer Fox danced with glee behind the bushes.

"I'm gonna kick the stuffin' out of you," Brer Rabbit said and pounced on the Tar Baby

with both feet. They sank deep into the Tar Baby. Brer Rabbit was so furious he head-butted the

cute little creature until he was completely covered with tar and unable to move.

Brer Fox leapt out of the bushes and strolled over to Brer Rabbit. "Well, well, what have

we here?" he asked, grinning an evil grin.

6th Grade: Unit 3

42

Brer Rabbit gulped. He was stuck fast. He did some fast thinking while Brer Fox rolled

about on the road, laughing himself sick over Brer Rabbit's dilemma.

"I've got you this time, Brer Rabbit," said Brer Fox, jumping up and shaking off the dust.

"You've sassed me for the very last time. Now I wonder what I should do with you?"

Brer Rabbit's eyes got very large. "Oh please Brer Fox, whatever you do, please don't throw me

into the briar patch."

"Maybe I should roast you over a fire and eat you," mused Brer Fox. "No, that's too much

trouble. Maybe I'll hang you instead."

"Roast me! Hang me! Do whatever you please," said Brer Rabbit. "Only please, Brer

Fox, please don't throw me into the briar patch."

"If I'm going to hang you, I'll need some string," said Brer Fox. "And I don't have any

string handy. But the stream's not far away, so maybe I'll drown you instead."

"Drown me! Roast me! Hang me! Do whatever you please," said Brer Rabbit. "Only

please, Brer Fox, please don't throw me into the briar patch."

"The briar patch, eh?" said Brer Fox. "What a wonderful idea! You'll be torn into little

pieces!"

Grabbing up the tar-covered rabbit, Brer Fox swung him around and around and then

flung him head over heels into the briar patch. Brer Rabbit let out such a scream as he fell that all

of Brer Fox's fur stood straight up. Brer Rabbit fell into the briar bushes with a crash and a

mighty thump. Then there was silence.

Brer Fox cocked one ear toward the briar patch, listening for whimpers of pain. But he

heard nothing. Brer Fox cocked the other ear toward the briar patch, listening for Brer Rabbit's

death rattle. He heard nothing.

Then Brer Fox heard someone calling his name. He turned around and looked up the hill.

Brer Rabbit was sitting on a log combing the tar out of his fur with a wood chip and looking

smug.

"I was bred and born in the briar patch, Brer Fox," he called. "Born and bred in the briar

patch."

And Brer Rabbit skipped away as merry as a cricket while Brer Fox ground his teeth in

rage and went home.

"Used with permission of S.E. Schlosser and AmericanFolklore.net. Copyright 2013. All rights

reserved."

Retrieved from: http://americanfolklore.net/folklore/2010/07/brer_rabbit_meets_a_tar_baby.html

6th Grade: Unit 3

43

Bud, not Buddy

Chapter 2

John Dillinger

During the 1930s Depression, many Americans, nearly helpless against forces they didn’t

understand, made heroes of outlaws who took what they wanted at gunpoint. Of all the lurid

desperadoes, one man, John Herbert Dillinger, came to evoke this Gangster Era and stirred mass

emotion to a degree rarely seen in this country.

Dillinger, whose name once dominated the headlines, was a notorious and vicious thief.

From September 1933 until July 1934, he and his violent gang terrorized the Midwest, killing 10

men, wounding 7 others, robbing banks and police arsenals, and staging 3 jail breaks—killing a

sheriff during one and wounding 2 guards in another.

John Herbert Dillinger was born on June 22, 1903 in the Oak Hill section of Indianapolis,

a middle-class residential neighborhood. His father, a hardworking grocer, raised him in an

atmosphere of disciplinary extremes, harsh and repressive on some occasions, but generous and

permissive on others. John’s mother died when he was three, and when his father remarried six

years later, John resented his stepmother.

In adolescence, the flaws in his bewildering personality became evident, and he was

frequently in trouble. Finally, he quit school and got a job in a machine shop in Indianapolis.

Although intelligent and a good worker, he soon became bored and often stayed out all night. His

father, worried that the temptations of the city were corrupting his teenage son, sold his property

in Indianapolis and moved his family to a farm near Mooresville, Indiana.

However, John reacted no better to rural life than he had to that in the city and soon

began to run wild again. A break with his father and trouble with the law (auto theft) led him to

enlist in the Navy. There he soon got into trouble and deserted his ship when it docked in Boston.

Returning to Mooresville, he married 16-year-old Beryl Hovius in 1924. A dazzling dream of

bright lights and excitement led the newlyweds to Indianapolis. Dillinger had no luck finding

work in the city and joined the town pool shark, Ed Singleton, in his search for easy money.

In their first attempt, they tried to rob a Mooresville grocer, but were quickly apprehended.

Singleton pleaded not guilty, stood trial, and was sentenced to two years in prison.

Dillinger, following his father’s advice, confessed, was convicted of assault and battery with

intent to rob and conspiracy to commit a felony, and received joint sentences of two to 14 years

and 10 to 20 years in the Indiana State Prison. Stunned by the harsh sentence, Dillinger became

a tortured, bitter man in prison.

“ John Dillinger” excerpt © www.fbi.gov. All rights reserved.

http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/history/famous-cases/john-dillinger/famous-cases-john-dillinger

6th Grade: Unit 3

44

Bud, not Buddy

Chapter 3

Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson was a famous African-American athlete, actor, write, scholar, lawyer and political

activist. Paul Robeson was born on April 9, 1898, in Princeton, New Jersey, to Anna Louisa and

William Drew Robeson. Robeson's mother died from a fire when he was 6 and his clergyman

father moved the family to Somerville, where the youngster excelled in academics and sang in

church. When he was 17, Robeson earned a scholarship to attend Rutgers University, the third

African American to do so, and became one of the institution's most stellar students. He received

top honors for his debate and oratory skills, won 15 letters in four varsity sports, was elected Phi

Betta Kappa and became his class valedictorian.

Bud, not Buddy

Chapter 4

Public Enemy Number One is a term which was first widely used in the United States in the

1930s to describe individuals whose activities were seen as criminal and extremely damaging to

society. The phrase was appropriated by J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI who used it to describe

various notorious fugitives that they were pursuing throughout the 1930s. The FBI's "Public

Enemies" were wanted criminals and fugitives who were already charged with crimes. Among

the criminals whom the FBI called "public enemies" were John Dillinger, Baby Face

Nelson, Bonnie and Clyde, Pretty Boy Floyd, Ma Barker, Al Capone, and Alvin Karpis.

J. Edgar Hoover was the founder and director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)

Federal Bureau of Investigation began in 1908 as the primary investigators of crime and terror

in the United States.

6th Grade: Unit 3

45

Bud, not Buddy

Chapter 5

Pretty Boy Floyd

http://www.biography.com/people/charles-pretty-boy-floyd-9542085 (short 3 minute video and reference

material)

Floyd was born in Georgia and grew up on a farm in Oklahoma. After an unlikely first career as a farmer,