National Memorial District of Columbia

advertisement

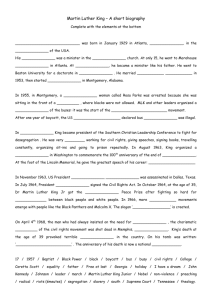

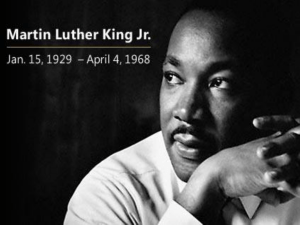

Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial National Memorial District of Columbia Library of Congress THE STRIDE TOWARDS FREEDOM A greater nation… A finer world. The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial honors a man of conscience; the freedom movement of which he was a beacon; and his message of freedom, equality, justice and love. It is the first on the National Mall devoted, not to a United States President or war hero, but a citizen activist for civil rights and peace. Dr. King, an African-American, brings "the image of America… the melting pot of the world" to the National Mall, but his message was universal. His non-violent philosophy pushed insistently towards the goal of the American Experiment - universal freedom and equality. His principled rhetoric illuminated the Nation's journey. With his life under constant threat, his last public talk left us this inspiration: "I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land." National Archives Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial National Memorial District of Columbia THE MEASURE OF A MAN Michael (later Martin) Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929 - April 4, 1968) was born in the segregated south of Atlanta, Georgia. After Morehouse College (B.A. Sociology), Crozer Theological Seminary (B. Divinity) and Boston University (D. Systematic Theology, 1955) he entered the Christian ministry. He married the perfect partner, Coretta Scott, in 1953 and took a pastorate in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1954, where he joined the leadership of the local NAACP, the Montgomery Improvement Association and served in the creation of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He was architect of the non-violent strategy for a Negro bus boycott protesting the city's arrest of Rosa Parks for sitting in a seat reserved for Whites. He asked his people "Are you able to accept blows without retaliating… to endure the ordeals of jail?" The answer was yes. The "Montgomery Movement" led to the integration of the city's buses and lit a contagious interracial fight for rights that spread to Washington and across the world. Dr. King received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, but he didn't rest on his laurels. National Archives THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s followed southern-state defiance of the Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education (1954) ruling that segregation was unconstitutional. Dr. King dove in and supported it without reserve: He assumed leading roles in Montgomery (1954); the Crusade for Voting Rights (his first speech at Lincoln Memorial, 1957); the Atlanta restaurant sit-in (1960); the intercity Freedom Riders and Albany (Georgia) Movement (1961); Birmingham Campaign (1963); the Children's Crusade for "freedom now" so their parents could see freedom before they died (1963); the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, from which his "I Have a Dream" still resounds (1963); St. Augustine, Florida, and Mississippi (1964); the Voting Rights March from Selma to Montgomery (1965); the Chicago drive against slums and poverty (1965); the "Meredith Mississippi March against Fear" (1966); and more. Frivolous arrests repeatedly landed him in jail and attracted Federal-authority attention to injustices to Blacks. Montgomery led to the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and 1960; Birmingham, to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which Dr. King was Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial National Memorial District of Columbia present to see President Johnson sign; Selma, to the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In 1967, expanding his message of peace, Dr. King spoke out against the Vietnam conflict (1959-1975), then at its height in casualties. National Archives THE MESSAGE An inescapable network of mutuality Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s message was both American and universal. In “Letter from Birmingham Jail” (1963) he cut to the quick of the freedom fighter’s disappointment in an America defying its ideals: “There can be no deep disappointment where there is no deep love.” However, he looked to an entire world in peace and a universal brotherhood: “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.” He saw the wide swath of the “arc of the moral universe:” Ancient-World forgers of self government, Augustus of a Republican Pax Romana, enlightened philosophers who imagined Utopia, Nonconformists of the 16th and 17th centuries who defied religious intolerance, Mahatma Gandhi, Allies of WWII, Eastern Block dissidents of the Velvet Revolutions of 1989. He saw with crystal clarity the role of America within that arc: American Revolutionary-war heroes, 600,000 CivilWar dead, Civil Rights Movement Freedom Fighters, Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, and others in a journey still in progress. He saw Henry David Thoreau’s civil disobedience and Gandhi’s nonviolent resistance as the best ways to achieve the goal of the American Experiment, and do-nothings as the greatest obstacle. His example compels us to pull our pound.