How to Solve a Phonology Problem

advertisement

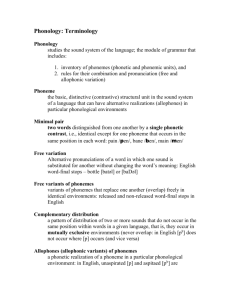

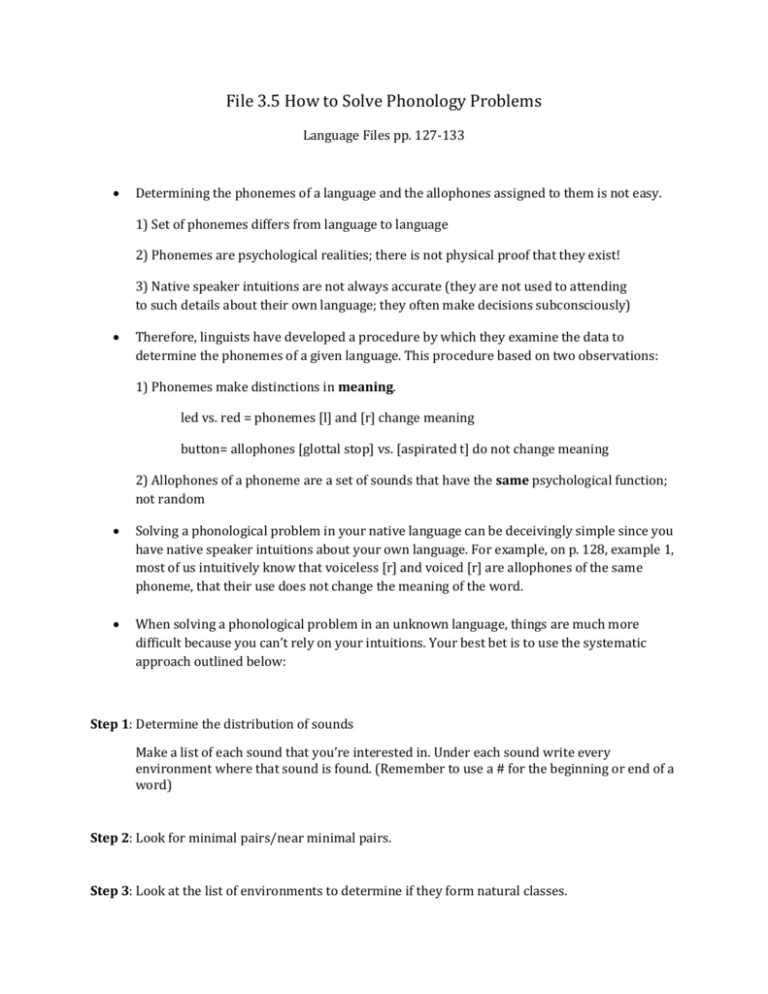

File 3.5 How to Solve Phonology Problems Language Files pp. 127-133 Determining the phonemes of a language and the allophones assigned to them is not easy. 1) Set of phonemes differs from language to language 2) Phonemes are psychological realities; there is not physical proof that they exist! 3) Native speaker intuitions are not always accurate (they are not used to attending to such details about their own language; they often make decisions subconsciously) Therefore, linguists have developed a procedure by which they examine the data to determine the phonemes of a given language. This procedure based on two observations: 1) Phonemes make distinctions in meaning. led vs. red = phonemes [l] and [r] change meaning button= allophones [glottal stop] vs. [aspirated t] do not change meaning 2) Allophones of a phoneme are a set of sounds that have the same psychological function; not random Solving a phonological problem in your native language can be deceivingly simple since you have native speaker intuitions about your own language. For example, on p. 128, example 1, most of us intuitively know that voiceless [r] and voiced [r] are allophones of the same phoneme, that their use does not change the meaning of the word. When solving a phonological problem in an unknown language, things are much more difficult because you can’t rely on your intuitions. Your best bet is to use the systematic approach outlined below: Step 1: Determine the distribution of sounds Make a list of each sound that you’re interested in. Under each sound write every environment where that sound is found. (Remember to use a # for the beginning or end of a word) Step 2: Look for minimal pairs/near minimal pairs. Step 3: Look at the list of environments to determine if they form natural classes. Step 4: Look for complementary gaps in the environments. (Is it true that one sound never appears in the same environment as the other sound? If so, they’re in complementary distribution and are allophones of the same phoneme. Step 5: State a generalization about the distribution of each sound. Write a “plain English” rule that that predicts where the sounds will occur. Step 6: Determine the identity of the phoneme and its allophones. Which is the basic allophone and which is the restricted allophone? (The basic allophone is the one that shows up in a variety of environments.) Step 7: Write a rule (using the appropriate symbols) that shows the process of each phoneme changing to an allophone. *******Remember***** phonemes always have slashes around them. Ex. /r/ allophones are represented as a phonetic transcription with bracket. Ex. [r] means “is pronounced as” a single slash (/) indicates the beginning of the environment specification So, a typical rule will go: /phoneme/ [allophone] / environment A couple of other reminders: Just because you don’t find a minimal pair doesn’t mean that you can just stop your analysis and conclude that the sounds you are looking at are different phonemes. Textbooks will always give you enough data to solve the problem, but they may not always give you minimal pairs. “Near-minimal pair” is a pair of words differing in meaning but phonetically identical except for two sounds in the same position of each word. Always start in the most immediate environment and work your way out. It’s more likely that the sounds directly around the sound you’re evaluating will be the conditioning environment. (However, it’s not unheard of sounds in adjacent syllables to be the conditioning factor—see the Finnish example in Section 3.2.3) Phonological processes are not usually random. Many of the phonological rules exist because of logical processes, such as assimilation or deletion. (See Section 3.2.3)