4.1 Why Take Samples (blank)

advertisement

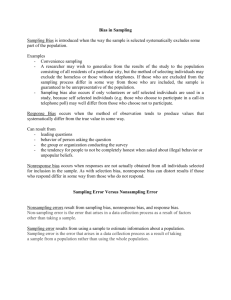

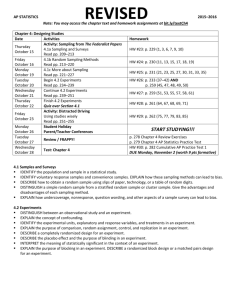

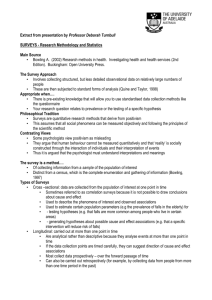

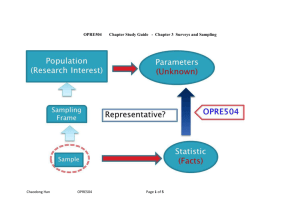

Chapter 4: Sample Surveys and Experiments Planning studies through designed surveys and experiments is one of the four major themes of AP Statistics. The overall goal of Chapter 4 is for you to learn good data collection strategies — how to design a survey by randomly selecting participants and how to design a sound experiment by randomly assigning treatments to subjects — that will allow generalization from a sample to a population or will establish cause and effect. 4.1 Why Take Samples, and How Not To The conclusions you get from exploratory data analysis (Chapter 2 – 3) only apply to the specific data you are examining. Often you want to answer questions about a large group of individuals. To get sound answers you must produce data in a way that is designed to answer your questions. Basic Terminology Population – the entire group of individuals that you want information about. Population size – the number of units in the population. Sample – the part of the population you actually examine in order to gather information. Sampling Frame – the list of the population from which you select the sample. Census – a special case of sampling, where information is collected from every unit in the entire population. Parameter – a numeric quantity (usually unknown) used to describe a characteristic of the population. Usually represented by Greek letters. Statistic - a numeric quantity collected from a sample of data, used to estimate a parameter. Usually represented by Latin letters. Hint: remember population (parameters) and sample (statistic). Bias: A Potential Problem with Survey Data When talking about sampling, the terms “nonrepresentative” and “biased” have different meanings. A sampling method is biased if on average the statistics it produces are larger or smaller than the population parameters being estimated. Nonrepresentative refers to the sample itself not looking like a small version of the population. A biased sampling method tends to result in nonrepresentative samples, but not always. Fathom Activity 4.1a: Time in the Hospital 1 4.1: Why Take Samples, and How Not To There are two ways in which you can get biased results: 1. Sample Selection Bias (Sample Bias) Sample selection bias arises from the method used to select the sample. In all types of sample selection bias the method of taking the sample tends to result in statistics that are systematically too high or too low on average. Size Bias: using a method that gives larger units a bigger change of being in the sample. Our activity “Time in the Hospital” is an example of this. Voluntary Response Bias: occurs when sample members are self-selected volunteers, as in voluntary samples. An example would be call-in radio shows that solicit audience participation in surveys on controversial topics (abortion, affirmative action, gun control, etc.). The resulting sample tends to overrepresent individuals who have strong opinions. Convenience Sampling: one in which the units chosen are those that are easy to include. Example: Interviewing people at a shopping mall as they walk by. This is easy because you just choose the people that walk by you as you’re standing there without any random mechanism. Sometimes the people could ignore you so it all depends on what you are surveying. Judgment Sampling: the sample is selected based on judgment. This is usually an extension of convenience sampling. For example, a researcher may decide to draw the entire sample from one "representative" city, even though the population includes all cities. When using this method, the researcher must be confident that the chosen sample is truly representative of the entire population. Inadequate Sampling Frame: the sampling frame (list of the population) is not a complete list of the population you want to sample from. 2. Response Bias Even well chosen samples can result in contaminated data. Response bias arises from the method of collecting the response rather than from the method of collecting the sample itself. The main sources of this bias are: Nonresponse bias: caused by people not responding to a survey, and these people may differ from those who do respond. For example, a sample survey on attitudes toward parenting may miss all working mothers selected for the sample if the people are contacted during working hours. Questionnaire bias: arises from how you ask the questions (tone of voice, appearance of interviewer, order of questions, etc.) and is often the result of leading questions, such as “Do you favor the new tax proposal?” rather than the more balanced “Do you favor or oppose the new tax proposal?” (People often say “yes” rather than offer a true opinion.) Incorrect response: results from intentional lying or inaccurate measuring devices. It often occurs in situations that ask for recall, such as “How many times did you eat vegetables this week?” (People often guess on the more acceptable high side.) 2 4.1: Why Take Samples, and How Not To