7. Consistency Theory: we seek the comfort of internal

advertisement

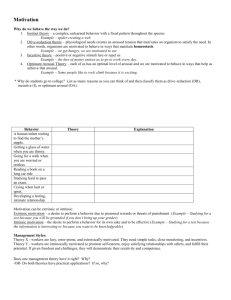

Summary of 22 Theories of Motivation Here are a number of academic theories about motivation. Source: http://changingminds.org/explanations/theories/a_motivation.htm 1. Acquired Needs Theory: we seek power, achievement or affiliation. 2. Affect Perseverance: Preference persists after disconfirmation. 3. Attitude-Behavior Consistency: factors that align attitude and behavior. 4. Attribution Theory: we need to attribute cause, that supports our ego. 5. Cognitive Dissonance: non-alignment is uncomfortable. 6. Cognitive Evalution Theory: we select tasks based on how doable they are. 7. Consistency Theory: we seek the comfort of internal alignment. 8. Control Theory: we seek to control the world around us. 9. Disconfirmation bias: Agreeing with what supports beliefs and vice versa. 10. ERG Theory: We seek to fulfill needs of existence, relatedness and growth. 11. Escape Theory: We seek to escape uncomfortable realities. 12. Expectancy Theory: We are motivated by desirable things we expect we can achieve. 13. Extrinsic Motivation: external: tangible rewards. 14. Goal-Setting Theory: different types of goals motivate us differently. 15. Intrinsic Motivation: internal: value-based rewards. 16. Investment Model: our commitment depends on what we have invested. 17. Opponent-Process Theory: opposite emotions interact. 18. Reactance Theory: discomfort when freedom is threatened. 19. Self-Determination Theory: External and internal motivation. 20. Self-Discrepancy Theory: we need beliefs to be consistent. 21. Side Bet Theory: aligned side-bets increase commitment to a main bet. 22. The Transtheoretical Model of Change: Stages in changing oneself. The following sections are numbered to correspond to the section numbers above. For each theory, a brief expansion is followed by thoughts on using the theory (see So what? sections below) 1. Acquired Needs Theory: we seek power, achievement or affiliation. Description. Need are shaped over time by our experiences over time. Most of these fall into three general categories of needs: Achievement (nAch); Affiliation (nAff); Power (nPow) Acquired Needs Theory is also known as the Three-Need Theory or Learned Need Theory. We have different preferences. We will tend have one of these needs that affects us more powerfully than others and thus affects our behaviors: Achievers seek to excel and appreciate frequent recognition of how well they are doing. They will avoid low risk activities that have no chance of gain. They also will avoid high risks where there is a significant chance of failure. Affiliation seekers look for harmonious relationships with other people. They will thus tend to conform and shy away from standing out. The seek approval rather than recognition. Power seekers want power either to control other people (for their own goals) or to achieve higher goals (for the greater good). They seek neither recognition nor approval from others -- only agreement and compliance. Identifying preferences. A common way of discovering our tendencies towards these is with a Thematic Apperception Test, which is a set of black-and-white pictures on cards, each showing an emotionally powerful situation. The person is presented with one card at a time and asked to make up a story about each situation. So what? Using it. Challenge achievers with stretching goals; Offer affiliation-seekers safety and approval. Beware of personal power-seekers trying to turn the tables on you or use other Machiavellian methods. Make sure you have sufficient power of your own, or show how you can help them achieve more power. Defending. Understand your own tendencies. Curb the excesses and, especially if you seek affiliation, beware of those who would use this against you and for their own benefit alone. 2. Affect Perseverance: Preference persists after disconfirmation. Description. Affect Perseverance occurs where an emotional preference continues, even after the thoughts that gave rise to the original emotion are invalidated. Feelings are often independent of facts and evidence, and once initiated tend to take on a life of their own. Almost by definition, they are not rational. Affect Perseverance is similar to Belief Perseverance. Research. Participants in a study by Sherman and Kim learned associations between neutral stimuli, Chinese ideographs and affectively valenced English words. They measured whether participants preferred the ideographs associated with positive English words to the ideographs associated with negative English words. Then they invalidated the cognition by associating new, neutral English words with the same ideographs. Despite this change in cognition, the affective preference persevered. Example. A woman falls in love with a man because he is kind to her. When he becomes abusive, her affection remains. So What? Using it. To get someone emotionally engaged with an item or topic, start with some rational purpose that makes sense to them. Then, when the emotions are established, slowly ignore and remove the rationale. Reinforce the emotion as its own justification. Defending. Pay attention to the rationale behind your feelings. Why do you feel that way towards things? What was the original reason? Is that reason still valid? 3. Attitude-Behavior Consistency: factors that align attitude and behavior. Description. Our attitudes (predispositions to behavior) and actual behaviors are more likely to align if the following factors are true: Our attitude and behavior are both constrained to very specific circumstances. There have been many opportunities to express attitude through behavior. We have a history of attitude-behavior consistency. The attitudes are based on personal experience, rather than being copied from others. The attitudes are proven by past experience. There is no social desirability bias, where the presence of others will lead us into uncharacteristic behavior. We are low in self-monitoring, so we do not distract The attitude is strongly held and is around core beliefs. So What? Using it. If you want people to behave in a certain way, check out the above list before assuming their attitude will actually lead to the desired behavior. Defending. Beware of causing confusion and sending mixed messages if you act outside of your visible attitudes. 4. Attribution Theory: we need to attribute cause, that supports our ego. Description. We all have a need to explain the world, both to ourselves and to other people, attributing cause to the events around us. This gives us a greater sense of control. When explaining behavior, it can affect the standing of people within a group (especially ourselves). When another person has erred, we will often use internal attribution, saying it is due to internal personality factors. When we have erred, we will more likely use external attribution, attributing causes to situational factors rather than blaming ourselves. And vice versa. We will attribute our successes internally and the successes of our rivals to external ‘luck’. When a football team wins, supporters say ‘we won’. But when the team loses, the supporters say ‘they lost’. Our attributions are also significantly driven by our emotional and motivational drives. Blaming other people and avoiding personal recrimination are very real self-serving attributions. We will also make attributions to defend what we perceive as attacks. We will point to injustice in an unfair world. We will even tend to blame victims (of us and of others) for their fate as we seek to distance ourselves from thoughts of suffering the same plight. We will also tend to ascribe less variability to other people than ourselves, seeing ourselves as more multifaceted and less predictable than others. This may well because we can see more of what is inside ourselves (and spend more time doing this). In practice, we often tend to go through a two-step process, starting with an automatic internal attribution, followed by a slower consideration of whether an external attribution is more appropriate. As with Automatic Believing, if we are hurrying or are distracted, we may not get to this second step. This makes internal attribution more likely than external attribution. Research. Roesch and Amirkham (1997) found that more experienced athletes made less self-serving external attributions, leading them to find and address real causes and hence were better able to improve their performance. So What? Using it. Beware of losing trust by blaming others (i.e. making internal attributions about them). Also beware of making excuses (external attributions) that lead you to repeat mistakes and leads to Cognitive Dissonance in others when they are making internal attributions about you. Defending. Watch out for people making untrue attributions. 5. Cognitive Dissonance: non-alignment is uncomfortable. Description. This is the feeling of uncomfortable tension which comes from holding two conflicting thoughts in the mind at the same time. Dissonance increases with: The importance of the subject to us. How strongly the dissonant thoughts conflict. Our inability to rationalize and explain away the conflict. Dissonance is often strong when we believe something about ourselves and then do something against that belief. If I believe I am good but do something bad, then the discomfort I feel as a result is cognitive dissonance. Cognitive dissonance is a very powerful motivator which will often lead us to change one or other of the conflicting belief or action. The discomfort often feels like a tension between the two opposing thoughts. To release the tension we can take one of three actions: Change our behavior. Justify our behavior by changing the conflicting cognition. Justify our behavior by adding new cognitions. Dissonance is most powerful when it is about our self-image. Feelings of foolishness, immorality and so on (including internal projections during decision-making) are dissonance in action. If an action has been completed and cannot be undone, then the after-the-fact dissonance compels us to change our beliefs. If beliefs are moved, then the dissonance appears during decision-making, forcing us to take actions we would not have taken before. Cognitive dissonance appears in virtually all evaluations and decisions and is the central mechanism by which we experience new differences in the world. When we see other people behave differently to our images of them, when we hold any conflicting thoughts, we experience dissonance. Dissonance increases with the importance and impact of the decision, along with the difficulty of reversing it. Discomfort about making the wrong choice of car is bigger than when choosing a lamp. Note: Self-Perception Theory gives an alternative view. Research. Festinger first developed this theory in the 1950s to explain how members of a cult who were persuaded by their leader, a certain Mrs Keech, that the earth was going to be destroyed on 21st December and that they alone were going to be rescued by aliens, actually increased their commitment to the cult when this did not happen (Festinger himself had infiltrated the cult, and would have been very surprised to meet little green men). The dissonance of the thought of being so stupid was so great that instead they revised their beliefs to meet with obvious facts: that the aliens had, through their concern for the cult, saved the world instead. In a more mundane experiment, Festinger and Carlsmith got students to lie about a boring task. Those who were paid $1 felt uncomfortable lying. Example: Smokers find all kinds of reasons to explain away their unhealthy habit. The alternative is to feel a great deal of dissonance. So what? Using it. Cognitive dissonance is central to many forms of persuasion to change beliefs, values, attitudes and behaviors. The tension can be injected suddenly or allowed to build up over time. People can be moved in many small jumps or one large one. Defending. When you start feeling uncomfortable, stop and see if you can find the inner conflict. Then notice how that came about. If it was somebody else who put that conflict there, you can decide not to play any more with them. 6. Cognitive Evalution Theory: we select tasks based on how doable they are. Description. When looking at task, we evaluate it in terms of how well it meets our needs to feel competent and in control. If we think we will be able to complete the task, we will be intrinsically motivated to complete the task, requiring no further external motivation. Cognitive Evaluation is occasionally also called Self-Perception Theory, although this confuses it with Bem's Self-Perception Theory. Example: If you tell me that I have to run for President, I will not exactly throw my heart into the job. If, however, you tell me how the local council is looking for someone like me, who wants to help in local schools, then I'll be there before you have finished the sentence! So what? When you ask someone to do something, if you want them to be motivated then ensure that it falls within their current level of competency. See also: Expectancy Theory, Extrinsic Motivation, Intrinsic Motivation, Over-justification Effect 7. Consistency Theory: we seek the comfort of internal alignment. Description. When our inner systems (beliefs, attitudes, values, etc.) all support one another and when these are also supported by external evidence, then we have a comfortable state of affairs. The discomfort of cognitive dissonance occurs when things fall out of alignment, which leads us to try to achieve a maximum practical level of consistency in our world. We also have a very strong need to believe we are being consistent with social norms. When there is conflict between behaviors that are consistent with inner systems and behaviors that are consistent with social norms, the potential threat of social exclusion often sways us towards the latter, even though it may cause significant inner dissonance. Ways we achieve consistency between conflicting items include: Denial or ignoring : 'I didn't see it happen.' Rationalization and excuses : 'It was going to fall anyway.' Separation of items :'I don't use my car enough to make a difference .' Transcendence : 'Nobody is perfect.' Changing item : 'I'll be more careful next time.' Persuasion : 'I'm good, really, aren't I?' Example. If you make a promise, you will feel bad if you do not keep it. So what? Using it. Highlight where people are acting inconsistently with beliefs, etc. that support your arguments. Show how what you want is consistent with the other person’s inner systems and social norms. Defending. You will always be inconsistent in some areas. When changing to fit in with the inconsistencies that someone else is pointing out, think about the other, potentially more serious, inconsistencies that you will be opening up. 8. Control Theory: we seek to control the world around us. Description. We have a deep need for control that itself, paradoxically, controls much of our lives. The endless effort to control can lead us to be miserable as we fail in this impossible task of trying to control everything and everyone around us. The alternative is to see the world as a series of choices, which is why Glasser later renamed Control Theory as Choice Theory. So what? Using it. Give people things to control, help them control the things in their path, or threaten their sense of control. Defending. Do not try to control everything -- instead see the world as a series of choices. 9. Disconfirmation bias: Agreeing with what supports beliefs and vice versa. Description. When people are faced with evidence for and against their beliefs, they will be more likely to accept the evidence that supports their beliefs with little scrutiny yet criticize and reject that which disconfirms their beliefs. Generally, we will avoid or discount evidence that might show us to be wrong. Research. Lord, Ross and Lepper had 24 each of pro- and anti-death penalty students evaluate faked studies on capital punishment, some of which supported the death penalty and some which did not. Students concluded that the studies that supported their views were superior to those that did not. Example. I am a scientist who is invited to investigate a haunted house. I rubbish the idea and decline the invitation. When given a paper which supports my pet theories, however, I laud the fine research with little questioning as to the methods used. So What? Using it. When you want to change beliefs, you may need to give significant evidence to overcome the disconfirmation bias. Defending. Try to be open when faced with evidence and viewpoints, even if it is contrary to what you know to be true. 10. ERG Theory: We seek to fulfill needs of existence, relatedness and growth. Description. Clayton Alderfer extended and simplified Maslow's Hierarchy into a shorter set of three needs: Existence, Relatedness and Growth (hence 'ERG'). Unlike Maslow, he did not see these as being a hierarchy, but being more of a continuum. Existence. At the lowest level is the need to stay alive and safe, now and in the foreseeable future. When we have satisfied existence needs, we feel safe and physically comfortable. This includes Maslow's Physiological and Safety needs. Relatedness. At the next level, once we are safe and secure, we consider our social needs. We are now interested in relationships with other people and what they think of us. When we are related, we feel a sense of identity and position within our immediate society. This encompasses Maslow's Love/belonging and Esteem needs. Growth. At the highest level, we seek to grow, be creative for ourselves and for our environment. When we are successfully growing, we feel a sense of wholeness, achievement and fulfilment. This covers Maslow's Self-actualization and Transcendence. So what? Using it. Find the relative state of the other person's needs for each of existence, relatedness and growth. Find ways of either threatening or helping to satisfy the needs. Defending. Know how well your own needs in this model are met, and what would threaten or improve them. Be careful when other people do things that threaten or promise to improve them. 11. Escape Theory: We seek to escape uncomfortable realities. Description. Many of the activities in which we indulge help us to get away from our lives or our characters with which we are not happy. These can be relatively harmless, such as sports or hobbies. they can also be hazardous and even fatal, including taking drugs and indulging in extreme sports. At the most extreme, some commit suicide to escape an unhappy life. In effect, we are trying to escape from our selves or some aspect of our character. Of course this cannot be done but this does not stop us from repeatedly trying. Research. Heatherton and Baumeister found significantly more dysfunction with regard to body esteem, suicidal ideation other irrational thoughts with those who indulged in binge drinking, as compared with non-binge-drinkers. Baumeister found escape behavior in such as sexual activities and suicide. Example: I have a boring and unfulfilling job and have difficulty sustaining love relationships. I often go out drinking with my friends at the weekend. So What? Using it. Offer people escape as a negotiation chip or to create a sense of reciprocity. You can also perhaps help people who you can see escaping, for example by enabling them to live more fulfilling lives. Defending. Note your own tendency to escape. Re-think your life and motivations as appropriate, getting help where you can. 12. Expectancy Theory: We are motivated by desirable things we expect we can achieve. Description. As we constantly are predicting likely futures, we create expectations about future events. If things seem reasonably likely and attractive, we know how to get there and we believe we can 'make the difference' then this will motivate us to act to make this future come true. Motivation is thus a combination of: Valence: The value of the perceived outcome (What's in it for me?) Instrumentality: The belief that if I complete certain actions then I will achieve the outcome. (Clear path?) Expectancy: The belief that I am able to complete the actions. (My capability?) Of course you can have an unpleasant outcome, in which case the motivation is now one of avoidance. Expectancy Theory is also called Valence-Instrumentality-Expectancy Theory or VIE Theory. So what? Motivate people to do something by showing them something desirable, indicating how straightforward it is to get it, and then supporting their self-belief that they can get there. 13.Extrinsic Motivation: external: tangible rewards. Description. Extrinsic motivation is when I am motivated by external factors, as opposed to the internal drivers of intrinsic motivation. Extrinsic motivation drives me to do things for tangible rewards or pressures, rather than for the fun of it. Example:Supermarkets use loyalty cards and discounts, airlines use air miles, companies use bonuses and commissions. Extrinsic motivation is everywhere. So what? Using it. You can offer positive motivations such as rewards and other bribery or you can use negative motivation such as threats and blackmail. Either way, extrinsic motivation is crude, easy and often effective. However it focuses people on the reward and not the action. Stop giving the reward and they’ll stop the behavior. This can, in fact, be useful when you want them to stop doing something: first give them extrinsic rewards for doing the unwanted behavior, then remove the reward. 14.Goal-Setting Theory: different types of goals motivate us differently. Description. In order to direct ourselves we set ourselves goals that are: Clear (not vague) and understandable, so we know what to do and what not to do. Challenging, so we will be stimulated and not be bored. Achievable, so we are unlikely to fail. If other people set us goals without our involvement, then we are much less likely to be motivated to work hard at it than if we feel we have set or directed the goal ourselves. Feedback. When we are working in the task, we need feedback so we can determine whether we are succeeding or whether we need to change direction. We find feedback (if it is sympathetically done) very encouraging and motivating. This includes feedback from ourselves. Negative self-talk is just as demotivating as negative comments from other people. Directional and accuracy goals. Depending on the type of goal we have, we will go about achieving it differently. A directional goal is one where we are motivated to arrive at a particular conclusion. We will thus narrow our thinking, selecting beliefs, etc. that support the conclusion. The lack of deliberation also tends to make us more optimistic about achieving the goal. An accuracy goal is one where we are motivated to arrive at the most accurate possible conclusion. These occur when the cost of being inaccurate is high. Unsurprisingly, people invest more effort in achieving accuracy goals, as any deviation costs, and a large deviation may well more. Their deliberation also makes them realize that there is a real chance that they will not achieve their goal. When we have an accuracy goal we do not get to a 'good enough' point and stop thinking about it--we continue to search for improvements. Both methods work by influencing our choice of beliefs and decision-making rules. Research. Tetlock and Kim motivated people to use accuracy goals by giving them a task and telling them they would have to explain their thinking. The people wrote more cognitively complex responses than the control group. So what? Using it. If you want someone to deliberately think about what they are doing, give them an accuracy goal. Defending. Choose your own goals. Notice the difference between when you are diving into action and when you are carefully thinking. 15. Intrinsic Motivation: internal: value-based rewards. Description. Intrinsic motivation is when I am motivated by internal factors, as opposed to the external drivers of extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation drives me to do things just for the fun of it, or because I believe it is a good or right thing to do. There is a paradox of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Intrinsic motivation is far stronger a motivator than extrinsic motivation, yet external motivation can easily act to displace intrinsic motivation (see the Overjustification Effect). Example: Most people's hobbies are intrinsically motivated. Notice the passion with which people collect little bits of china or build detailed model ships. Few people carry that amount of passion into their workplace. So what? Using it. If you can get someone to believe in an idea or align their values with what you want, then you have set very powerful motivation in place. Seek to make them feel good about what you want. Also minimize extrinsic motivation. So, for example, pay them fairly, then do everything to keep money out of the equation of why they come to work. 16. Investment Model: our commitment depends on what we have invested. Description. Our commitment to a relationship depends on how satisfied we are about: Rewards and costs and what we see as a fair balance. A comparison with potential alternative relationships How much we have already invested in the relationship. Investments can be financial (like a house), temporal (such as time spend together) or emotional (such as in the welfare of the children). Investments can thus has a ‘sunk cost’ effect, where a person stays in a relationship simply because they have already invested significantly in it. Research. Rusbult tracked relationships of college students. Their satisfaction and investment were key predictors staying in the relationship, with availability of alternatives as a trigger for getting out. Example: Cults often have a sequence of 'inner circles', each of which requires increasing investment. To get through these doors cult members have to donate their worldly wealth, go through bizarre rituals, learn lengthy texts, and so on. So what? Using it. To keep a person in a relationship, get them to invest heavily in it. Defending. If you are unhappy with a relationship, remember that the past is past. Look to the future and what you can get there rather than what you have spent and can never retrieve. All you have is the rest of your life. 17. Opponent-Process Theory: opposite emotions interact. Description. We have pairs of emotions that act in opposing pairs, such as happiness and sadness, fear and relief, pleasure and pain. When one of these is experienced, the other is temporarily suppressed. This opposite emotion, however, is likely to re-emerge strongly and may curtail or interact with the initial emotion. Thus activating one emotion also activates its opposite and they interact as a linked pair. To some extent, this can be used to explain drug use and other addictive behavior, as the pleasure of the high is used to suppress the pain of withdrawal. Sometimes these two conflicting emotions may be felt at the same time as the second emotion intrudes before the first emotion wanes. The result is a confusing combined experience of two emotions being felt at the same time that normally are mutually exclusive. Thus we can feel happy-sad, scared-relieved, love-hate, etc. This can be unpleasant but as an experiential thrill it can also have a strangely enjoyable element (and seems to be a basis of excitement). Research. Solomon and Corbit (1974) analyzed the emotions of skydivers. Beginners experienced extreme fear in their initial jump, which turned into great relief when they landed. With repeated jumps, the fear of jumping decreased and the post-jump pleasure increased. Example. A person buys something to cheer themselves up but later feels guilty at having spent so much. So they buy something else to cheer up again. A thrill seeker goes rafting. The excitement of the journey is a mix of fear of the next rapids and relief at having survived the last one. So What? Using it. To stop a person feeling one thing, stimulate the opposite emotion. Tell people good and bad news in close succession. Then in the confusion get them to agree to your real request. Defending. When you are stimulated to feel one emotion, pause and think about the future: will the opposite appear afterwards? Is this what you want? When you feel conflicting emotions, take care not to agree to anything. Calm down first. 18. Reactance Theory: discomfort when freedom is threatened. Description. When people feel that their freedom to choose an action is threatened, they get an unpleasant feeling called ‘reactance’. This also motivates them to perform the threatened behavior, thus proving that their free will has not been compromised. Research. Pennebaker and Sanders (1976) put one of two signs on college bathroom walls. One read ‘Do not write on these walls under any circumstances’ whilst the other read ‘Please don’t write on these walls.’ A couple of weeks later, the walls with the ‘Do not write on these walls under any circumstances’ notice had far more graffiti on them. Example: When persuading my children, I have to be careful because I know that if I push too hard they will do what I have told them not to do, just to show me who is really in charge! So what? Using it. Beware of persuading too overtly or too much. If people get wind that they are being railroaded, they will leap right off the tracks. 19. Self-Determination Theory: External and internal motivation. Description. People have an external 'perceived locus of causality' (PLOC) to the extent they sees forces outside the self as initiating, pressuring, or coercing one’s action. In an internal PLOC a person feels they are the initiator and sustainer of their own actions. People with a higher internal PLOC thus feel selfdetermined in that they see their behavior as stemming from their own choices, values, and interests, whereas those with an external PLOC experience their behavior as controlled by some external event, person, or force. The internal locus is connected with intrinsic motivation, whilst the external locus is connected with extrinsic motivation. The distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic is a core part of SDT, which was developed in the wake of Behavioralism and Conditioning, where behavior management is based around reward and punishment. SDT extends this extrinsic view to consider intrinsic effects. Example: I feel in control of my own life. I feel responsible for my actions. I have a high internal locus and motivate myself. My friend is always complaining that they are being 'forced' to do things and that life is not fair. They have a high external locus and are more affected by reward and punishment. So What? Using it. Find out whether people have stronger internal or external locus and then persuade them accordingly. For internal locus, you might show how they are control and let them choose. For external locus you could show how they are being driven by outer forces and then offer a safe haven for them. Defending. Understand your own PLOC and how you attribute cause. Think about whether this is effective for you and whether you want to change it. Also note how this relates to how others persuade you (and how you persuade yourself). 20. Self-Discrepancy Theory: we need beliefs to be consistent. Description. We are strongly motivated to maintain a sense of consistency among our various beliefs and self-perceptions. This causes problems as there are invariably differences between our aspirations for ourselves and our actual behaviors. When the actual experience is somewhat less than we think we can achieve, we tend to feel a pattern of feelings such as sadness, dissatisfaction and other depressive senses. When experience is less that we feel we should achieve, we experience fear, worry and other anxieties. As with other dissonance effects, we will act to reduce this dissonance by various means. Example: When someone has a car accident that hurts someone else, the thought that they are to blame can make them feel very uncomfortable. So what? Using it. Build tension by showing them how they are less than perfect. Defending When you are feeling unhappy, ask why. Ask who could have prodded you into that state. 21. Side Bet Theory: aligned side-bets increase commitment to a main bet. Description. We make choices based on assumptions about the world around us and previous decisions we have made. In this we make 'side bets' that are based on a main bet or activity succeeding. If we fail at the main bet then we also lose the side bet. The side bets thus increase commitment to the main bet. As Becker said: "Commitments come into being when a person, by making a side-bet, links extraneous interests with a consistent line of activity." In the same vein a reverse effect occurs in hedging activity. If we make a side bet on which we win if the main bet fails, then our commitment to the main bet fails. Research. Aranya and Jacobson, in a study of systems analysts, found a direct correlation between age, marital status, number of children and salary, showing that older people with higher salaries make side bets in additional commitments around marriage and having children that effectively increases their commitment to their jobs. Example: A person refuses to change to a job with a higher salary because the new job is higher risk in terms of potential failure and the person has made a side-bet of buying a new house based on the assumption of a continued and stable income. So What? Using it. Increase commitment by getting people to make side-bets on which they gain more if the target commitment is completed. \ Defending. Be cautious about getting too deep into things, particularly when people who want you to do things encourage you to do related things. In such cases it may be wise to hedge your bets, finding ways to be able to extricate yourself with minimum damage should things go wrong. 22. The Transtheoretical Model of Change: Stages in changing oneself. Description. We go through a number of stages when faced with a need to change or take action. Precontemplation: Unaware of problem, not thinking of or wanting to change. Contemplation: Aware of problem and thinking about taking action. Preparation: Getting emotionally ready. Intending to act. Action: Taking the necessary action. Maintenance: Keeping up the necessary action. Not backing out or slowing down. Termination: Ending at the appropriate point. Not becoming 'institutionalized'. This model is particularly applicable for such as addiction and health, where the person is not likely to be easily willing to change. Example: An addict starts out happily addicted, but then gradually becomes aware of the down-side addiction. They think for a long time about doing something and eventually decide they must act. There is still a while before they take action. It is difficult to keep going and many others being treated drop out and go back to addiction. With support, however, the addict gets to the end of the treatment and transitions to a new life. So What? Using it. When you are helping someone change, think about where they are at the moment and how to get them to the next step, not just straight into action.