Mrs. Midas Poetry Analysis by Carol Ann Duffy

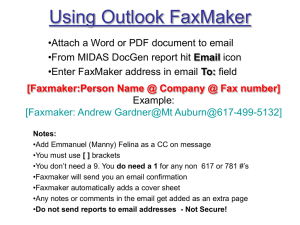

advertisement

Poetry analysis: Mrs Midas, by Carol Ann Duffy by John Welford “Mrs Midas” is one of the poems included in Carol Ann Duffy’s 1999 collection “The World’s Wife”. In this collection she used wit and humour to great effect to debunk the pretentiousness of men down the centuries. Figures from history and myth were perceived from an irreverent female perspective to make a series of incisive comments about woman’s place in the world and also to reveal aspects of her own complex psychology. The myth on which the poem is based is the story first told by Ovid in his “Metamorphoses”. Midas, king of Phrygia, is granted a wish by the god Dionysus and his greed prompts him to ask that everything he touches will turn to gold. The wish comes true but Midas soon comes to regret his choice, given that life becomes impossible if every morsel of food one touches changes into hard yellow metal. Midas is forced to ask Dionysus to reverse the spell. Carol Ann Duffy’s poem tells the story as though it was happening in 20th century Britton, with herself as the wife of King Midas, although the name only appears in the poem’s title and there is no indication in the poem that anyone is royal or has a particularly elevated station in life. The name “Pan” is used once (a passing reference to another aspect of the King Midas legend) but that is the only link to the classical original apart from the consistent theme of the “touch of gold”. The poem comprises eleven six-line unrhymed stanzas. It reads almost like prose with plenty of run-on lines and not much evidence of rhythm in the diction. However, there is plenty of rhythm in the ideas, as concepts build on each other and relationships between concepts become clear to the reader. It is a poem that works well when read aloud, because the reader can add pauses that emphasise the links, and a number of these only become clear on a second or third reading when the words are read on the page. The poem opens with a scene of domestic order and normality. The narrator begins with the date (“late September”) and a description of the evening meal being cooked. Words such as “unwind” and “relaxed” serve to set the tone. Because the room is getting steamy, she opens a window and then sees her husband in the garden, “standing under the pear tree snapping a twig”. The references to touching are noticeable but are presented subtly in this stanza. She has poured a glass of wine but noticed the steam on “the other’s glass” which she wipes “like a brow”, thus also conveying the loving relationship enjoyed by the couple. Likewise the “steamy breath” from the stove is “gently blanching the windows”. The second stanza describes what she sees through the window. The second line is particularly effective and has a bearing on what follows: “the dark of the ground seems to drink the light from the sky”. At this stage the reader does not know what is about to happen, but the concept of a life-force being drained and replaced by something evil is well expressed here. Immediately after this line the first odd thing happens: “that twig in his hand was gold”, and from this point on the poem descends into strangeness. The narrator seeks to find a rational explanation for what she is seeing. At first she throws in an irrelevant reference to the ordinary by stating the variety of pear that her husband is plucking from the tree (“we grew Fondante d’Automne”) and then wonders if the strange appearance of the pear in his hand (“it sat in his palm like a light bulb. On.”) is because he is “putting fairy lights in the tree”. However, further odd things happen, as described in the following stanzas. Midas becomes king-like when he sits in his chair that is now “a burnished throne” and his expression is “strange, wild, vain”. Thoughts of fairy lights change to something much grander and more remote, namely “the Field of the Cloth of Gold and of Miss Macready”. The first reference is to the event in 1520 when King Henry VIII of England met King Francis I of France with no expense spared. Miss Macready can be taken to be the history teacher from whom Mrs Midas would have gleaned that particular piece of knowledge. Weirdness and absurdity arrive in close order. Under such circumstances, would the average housewife continue to serve dinner? Mrs Midas does, with the result that the corn on the cob turns into “the teeth of the rich” when spat out by her husband, and the wineglass is transformed when he picks it up to drink (“glass, goblet, golden chalice”). As the chatty Mrs Midas tells the tale, she cannot resist the irrelevant mention of the wine as “a fragrant, bone-dry white from Italy”. Comedy and horror are cleverly intertwined. Mrs Midas describes how she made Midas tell his story, and the precautions she took to ensure that he kept “his hands to himself” although “the toilet I didn’t mind”. Presumably the thought of sitting on a golden throne was one that appealed to her! The wordplay at this stage is extremely good: “Look, we all have wishes; granted. / But who has wishes granted?” And, apart for the golden toilet mentioned above, there is a bright side in that, as she said to her husband, “you’ll be able to give up smoking for good”. However, there is a noticeable change of mood in the second half of the poem as a note of tenderness enters. The realization that the couple must now lead separate lives is the ultimate horror for a woman who has clearly loved her husband. They had been, as she says, “passionate then, / in those halcyon days; unwrapping each other, rapidly, / like presents”. In the eighth stanza she dreams that she bears Midas’s golden child with its “perfect ore limbs” and “amber eyes”. She wakes to “the streaming sun”, which is the only golden shower that is acceptable and conducive to life because “who, when it comes to the crunch, can live / with a heart of gold?” She tells how Midas had to move out and live in a caravan in the woods, leaving her as “the woman who married the fool / who wished for gold”. She visits him from time to time, following his golden footsteps and other evidence of his folly. He tells her that he can hear “the music of Pan / from the woods”. Sounds are not corruptible into gold, but this, for his wife, is “the last straw”. The final stanza brings the whole matter home and gives the story its universal meaning. Mrs Midas explains that what really hurts is “not the idiocy or greed / but lack of thought for me”. She still loves her husband although they can never be together. She thinks about him frequently and, as is typical with people who are forced apart for whatever reason, things she sees can suddenly remind her of him and what she has lost (“once a bowl of apples stopped me dead”). The final line is one that could be spoken by millions of women who have lost their life partner: “I miss most, even now, his hands, his warm hands on my skin, his touch” (the last word of the poem being the most significant). Of course, the situation described in the poem is “fantastic” in the true sense of that word, but the sentiment is real enough. Relationships are often ruined through idiocy or greed, and there have been millions of Midases who thought that being rich would bring them contentment. Ironically, it is Mrs Midas who is now rich (“I sold / the contents of the house”) but neither she nor her husband have gained anything worthwhile from being so. “Mrs Midas” is an excellent poem that manages to combine wit and humour with a strong and important message. Mrs Midas comes across as being warm and sympathetic and the possessor of a true “heart of gold”. In all the poems of this collection Carol Ann Duffy put a considerable amount of herself. When the reader or hearer experiences this poem they know that this is how the poet would feel were she to be put in the mythical situation she describes. Likewise, the reader can appreciate that this is a real situation for far too many people in the world today, and the response is a genuine one that is expressed, at the end, with tenderness and compassion.