cognitive, personality, and biological factors underlying

advertisement

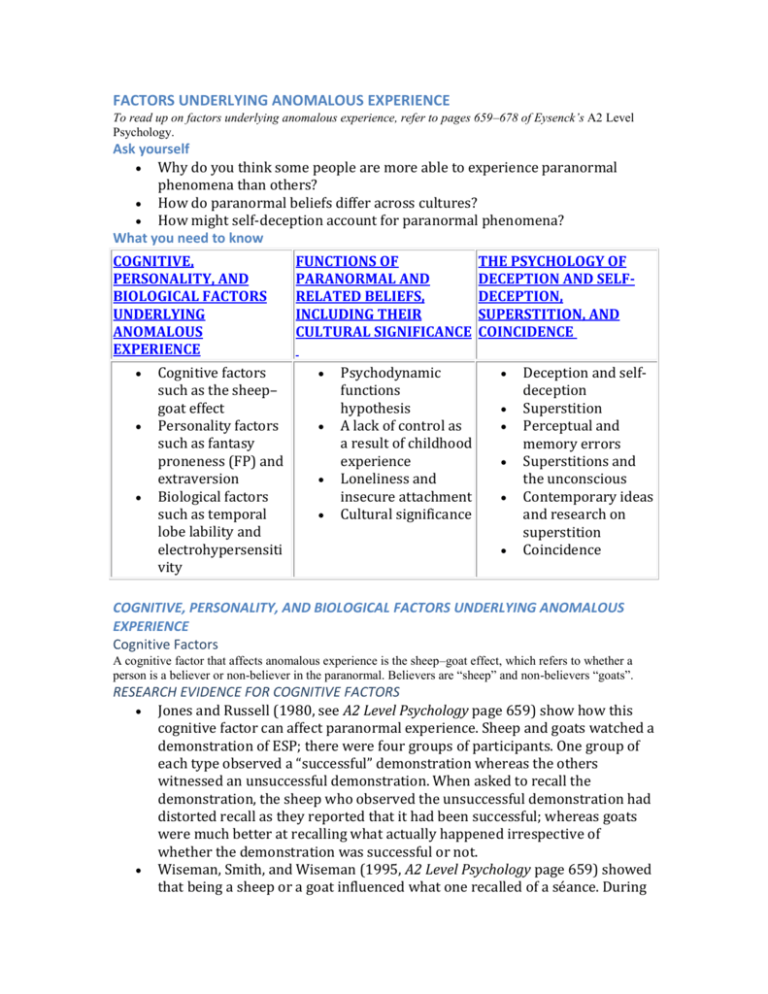

FACTORS UNDERLYING ANOMALOUS EXPERIENCE To read up on factors underlying anomalous experience, refer to pages 659–678 of Eysenck’s A2 Level Psychology. Ask yourself Why do you think some people are more able to experience paranormal phenomena than others? How do paranormal beliefs differ across cultures? How might self-deception account for paranormal phenomena? What you need to know COGNITIVE, PERSONALITY, AND BIOLOGICAL FACTORS UNDERLYING ANOMALOUS EXPERIENCE Cognitive factors such as the sheep– goat effect Personality factors such as fantasy proneness (FP) and extraversion Biological factors such as temporal lobe lability and electrohypersensiti vity FUNCTIONS OF PARANORMAL AND RELATED BELIEFS, INCLUDING THEIR CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE Psychodynamic functions hypothesis A lack of control as a result of childhood experience Loneliness and insecure attachment Cultural significance THE PSYCHOLOGY OF DECEPTION AND SELFDECEPTION, SUPERSTITION, AND COINCIDENCE Deception and selfdeception Superstition Perceptual and memory errors Superstitions and the unconscious Contemporary ideas and research on superstition Coincidence COGNITIVE, PERSONALITY, AND BIOLOGICAL FACTORS UNDERLYING ANOMALOUS EXPERIENCE Cognitive Factors A cognitive factor that affects anomalous experience is the sheep–goat effect, which refers to whether a person is a believer or non-believer in the paranormal. Believers are “sheep” and non-believers “goats”. RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR COGNITIVE FACTORS Jones and Russell (1980, see A2 Level Psychology page 659) show how this cognitive factor can affect paranormal experience. Sheep and goats watched a demonstration of ESP; there were four groups of participants. One group of each type observed a “successful” demonstration whereas the others witnessed an unsuccessful demonstration. When asked to recall the demonstration, the sheep who observed the unsuccessful demonstration had distorted recall as they reported that it had been successful; whereas goats were much better at recalling what actually happened irrespective of whether the demonstration was successful or not. Wiseman, Smith, and Wiseman (1995, A2 Level Psychology page 659) showed that being a sheep or a goat influenced what one recalled of a séance. During the séance participants were asked to try to move objects placed in the centre of the table. In reality, nothing ever moved. Sheep were much more likely (40%) to report an object had moved than were disbelievers (14%). Also, 20% of believers thought that something genuine had occurred; this was 0% in the disbeliever group. Cognitive biases can also affect people’s belief in horoscopes (Wiseman & Smith, 2002, see A2 Level Psychology page 660). Eighty participants were asked to read and judge four horoscopes, two of which were labelled “reading from your birth sign”, and the other two were labelled “reading from another birth sign”. These were counterbalanced for each participant, but all read the same four horoscopes. Prior to this, all participants completed the Belief in Astrology Questionnaire. The findings showed cognitive biases do affect horoscope readings as believers gave much lower generality scores than disbelievers on all horoscopes and higher accuracy ratings. EVALUATION OF COGNITIVE FACTORS Natural experiments. The above research studies are all natural experiments because they test for a naturally occurring difference between sheep and goats. The problem with this is that without a manipulated IV we cannot control cause and effect and so we cannot conclude that being a sheep is a causative factor in anomalous experience. Personality Factors One such personality trait that may affect anomalous experience is fantasy proneness (FP) and another is extraversion. RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR PERSONALITY FACTORS Wilson and Barber (1983, see A2 Level Psychology page 661) proposed the personality trait fantasy proneness based on their study of 27 excellent hypnotic females (the FP group) and a control group of 26 females who weren’t. They found that the majority of the FP group thought that their toys had feelings and emotions, they assumed the roles of fantasy characters during play, and they were praised by parents for fantasy play. As adults the FP group spent more time fantasising during the day, experience fantasies as “real as real”, have psychic abilities, and experience apparitions. Gow et al. (2001 see A2 Level Psychology page 661) researched FP in a sample of people who claimed to have seen a UFO or experienced an alien abduction and compared them with a control group. They found reporting any type of UFO experience was linked to heightened levels of FP and stronger beliefs in paranormal activity. Parra and Villaneuva (2003, see A2 Level Psychology page 662) tested 30 participants, all of whom completed the Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI) and a Pre-Ganzfeld Questionnaire. The latter questionnaire measured relaxation, mood, motivation, and expectation of success. The EPI measures level of extraversion, a personality trait characterised by being outgoing and seeking new experiences, and so it was predicted that extraverts would manifest psi better than introverts. The results clearly demonstrated that extraverts scored significantly better at ESP than the introverts. RESEARCH EVIDENCE AGAINST PERSONALITY FACTORS Roberts (1997, see A2 Level Psychology page 661) noted that, at the time he reviewed the evidence, only three main studies had been conducted (Ring & Rosing, 1990; Bartholomew et al., 1991; Spanos et al., 1993), of which only one had noted any significant link to FP. It is therefore unclear as to the role of FP in experiences. EVALUATION OF PERSONALITY FACTORS Cause and effect. The measures of fantasy proneness were taken post-event, and so there is no way of clearly seeing if the FP caused the experience or the experience caused the FP! This is also a weakness of the natural experimental method because personality type cannot be manipulated as an IV, then association rather than causation can be established. This means we cannot say that FP causes anomalous experience. Control group. The use of control groups is a useful control as this enables comparisons to be made. Extraversion as a confounding variable. This research on extraversion shows that personality could bias the findings of ESP–Ganzfeld studies, so this could be another confounding variable reducing the validity of the findings. However, parapsychologists would counter this with the fact that this just shows certain types of people are more receptive to ESP. Sample bias. The small sample size means the findings have limited generalisability. Researcher bias. It is possible that the researchers’ expectations cued the participants in some way and so the findings are due to this rather than real differences between the different groups of participants. Self-report. The self-report nature of the surveys mean that the findings are weakened by biases such as demand characteristics (guessing the aim of the researcher and providing the results that are wanted) and social desirability (exaggerating or minimising characteristics to in order to present themselves in the best possible light. Biological Factors Two key biology factors that may underpin paranormal experiences are temporal lobe lability and electrohypersensitivity, and both of these may be linked. RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR BIOLOGICAL FACTORS The Temporal Lobe Lability Hypothesis was proposed by Persinger (1983, see A2 Level Psychology page 662). He proposed the temporal lobe has the lowest electrical output, and so it would be most affected by electromagnetism. The temporal lobe houses memories and fantasies so, if over-stimulated, people could have strange occurrences. Persinger produced many papers showing differing levels of correlation between temporal lobe stimulation and paranormal beliefs and experiences. Persinger claimed he could “induce” an alien abduction experience in the laboratory by stimulating the temporal lobes. Blackmore (1994, see A2 Level Psychology page 663) tested Persinger’s claim for a Horizon programme on the BBC, and has provided confirmation of Persinger’s findings. She wore a special helmet that directly stimulated the temporal lobes via magnetic fields, whilst sitting in a dimly lit room with ping-pong balls over her eyes. After about 10 minutes, she reported an abduction-like experience as she felt as if two hands had grabbed her and were pulling her upwards followed by having her leg pulled, distorted, and dragged up to the ceiling! Research (Budden, 1994, see A2 Level Psychology page 663) on electrohypersensitivity (which refers to the idea that some people are more affected by electromagnetic output than others) consisted of case studies and anecdotal evidence linking a range of electromagnetic sources to apparitions and alien abduction experiences. For example, many people who claim visitations appeared to live near electricity sub-stations, mobile-phone transmitters, pylons, or television masts. Thus, it was concluded that electromagnetic “pollution” was causing anomalous experiences, especially ghosts and alien visitation, and that those who are electrically hypersensitive are more affected by electromagnetic pollution. Jawer (2006, see A2 Level Psychology page 664) studied 112 participants, 62 of whom were “sensitives” and 50 comprised a control group. “Sensitives” reported significantly more allergies and electrical sensitivity (had been struck by lightening and had been affected by electrical appliances) and seeing more apparitions and objects moving than the controls and so supports the link between electrohypersensitivity and paranormal experiences. RESEARCH EVIDENCE AGAINST BIOLOGICAL FACTORS Blackmore and Cox (2000, see A2 Level Psychology page 663) tested out the Temporal Lobe Lability Hypothesis in 12 people claiming alien abduction. They were compared with 12 matched controls and a group of students. All participants completed the Personal Philosophy Inventory, which is designed to measure temporal lobe lability. However, the abductees scored lower on temporal lobe lability. They were also asked about their experience of sleep paralysis and the “abductee” group scored significantly higher in terms of indicators of sleep paralysis. Thus, it was concluded that experience of alien abduction may be more linked to a sleep paralysis episode than temporal lobe lability. Spanos et al. (1993; see A2 Level Psychology page 663) discovered no difference between an alien abduction group and control group on a questionnaire measuring temporal lobe lability, therefore further contradicting Persinger’s claims. EVALUATION OF BIOLOGICAL FACTORS Cause and effect. The findings on temporal lobe lability and electrohypersensitivity correlations do not state cause and effect. Lack of scientific evidence. Budden never tested out these ideas and simply stuck to producing endless case study accounts of the after-effects. The ideas were not tested experimentally or prospectively to “predict” visitations and visions. Lack understanding of electrohypersensitivity. Further research is needed to pinpoint the exact mechanisms that cause electrohypersensitivity. Reductionist. The idea that temporal lobe lability and electrohypersensitivity cause parapsychology experience is reductionist as this ignores other factors, and, of course, research shows that cognitive, personality, and many other factors are likely to play a part. FUNCTIONS OF PARANORMAL AND RELATED BELIEFS, INCLUDING THEIR CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE Psychodynamic Functions Hypothesis One reason suggested for why people hold these beliefs is based on psychodynamic psychology. The Psychodynamic Functions Hypothesis suggests early trauma (e.g. abuse) can lead to a belief in the paranormal. Irwin (1992, see A2 Level Psychology page 664) suggests childhood trauma leads to childhood fantasy (e.g. high imagination, prone to fantasy play, etc.) as a coping mechanism and this means the trauma can be repressed into the unconscious. This manifests itself as either a paranormal experience or a stronger belief in paranormal activities during adolescence and adulthood. RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR PSYCHODYNAMIC FUNCTIONS Lawrence et al. (1995, see A2 Level Psychology page 665) tested the hypothesis using 80 students from the University of Edinburgh. They completed measures on traumatic childhood experiences, belief in the paranormal, and childhood fantasy. The initial correlations showed some relationship between childhood trauma and paranormal experience, and also with childhood fantasy. However, the correlation between childhood trauma and paranormal belief just missed out on significance (P < 0.06). As a result of this, Lawrence et al. modified the theory by stating childhood trauma can affect paranormal experience, which in turn affects paranormal beliefs. A lack of control as a result of childhood experience The Psychodynamic Functions Hypothesis has been expanded to give a broader theory. The concept of control and whether this is internal (feel have control of life) or external (feel external factors have control), as suggested by Rotter (1954, see A2 Level Psychology page 665), has been added to the theory. External locus of control is more closely associated with paranormal belief and so Irwin (2005, see A2 Level Psychology page 665) suggests that paranormal beliefs arise because of a lack of control brought about not just by childhood abuse/trauma but any childhood experience characterised by a lack of control (e.g. having older siblings, having authoritarian parents, moving house a lot). RESEARCH EVIDENCE FOR A LACK OF CONTROL Watts, Watson, and Wilson (2007, see A2 Level Psychology page 665) tested the theory using 127 students from the University of Edinburgh. They completed a range of questionnaires including ones on paranormal beliefs and perceived childhood control. Irwin’s merged theory is supported because when belief in the paranormal increased, perceived childhood control decreased. This led to the conclusion that a lack of control in childhood leads to insecurity and helplessness, and so this leads to a fantasydriven unconscious mechanism to cope with everyday uncertainty. Loneliness and insecure attachment Rogers, Qualter, and Phelps (2007, see A2 Level Psychology page 666) proposed that loneliness and/or attachment style affected paranormal belief. Thus, paranormal experience may be a way of dealing with loneliness and childhood insecurity, in particular, the avoidant attachment style may be able to explain paranormal beliefs because it follows the Psychodynamic Functions Hypothesis idea that we ignore and avoid dealing with the traumatic events of childhood. RESEARCH EVIDENCE INTO LONELINESS AND INSECURE ATTACHMENT Over 250 participants from a range of backgrounds completed questionnaires measuring paranormal beliefs, childhood trauma, loneliness, and attachment style. Childhood trauma was the strongest predictor of paranormal beliefs but other factors were also found to have a significant effect, such as proneness to fantasy and social loneliness. Insecure attachment and belief in the paranormal showed some relationship but not a strong one. EVALUATION OF RESEARCH INTO LONELINESS AND INSECURE ATTACHMENT Self-report biases. One drawback from this line of research is that all studies are using questionnaires so we cannot rule out demand characteristics, social desirability, and faulty memories affecting the findings. Multi-factorial. The number of factors identified shows that paranormal belief is clearly multi-factorial and further research needs to be conducted in this area to fully understand all of these links. Cultural significance The functions of belief in the paranormal are culturally relative, which means they differ across cultures. Therefore, one culture may perceive a paranormal activity to be that—paranormal—yet another may see it as a human-based skill. RESEARCH EVIDENCE INTO CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE Jahoda (1969, see A2 Level Psychology page 667) highlights research on a tribe in New Guinea. Whiting studied their beliefs in ghosts, sorcery, and a huge monster called marsalai and he was convinced that this was a simple case of stimulus generalisation. That is, the New Guinea peoples were simply generalising fear from real dangers onto paranormal dangers. Sleep paralysis is another example of how culture affects what is perceived as paranormal experience. Sleep paralysis occurs when a person is simultaneously awake and asleep during the rapid eye-movement (REM) phase of sleep. A presence is often felt in the room that usually touches or sits on the person having the paralysis. Many cultures see this as being paranormal in nature, as highlighted below. For example, in Thai and Cambodian culture, the experience is called “pee umm”, which is the perception that ghostly figures hold you down during sleep. In Southern China (Hmong culture), it is referred to as “dab tsog”, which means “crushing demon”. In Hungary, the experience is definitely more paranormal as they tend to blame witches, fairies, and demon lovers. The Kurdish people keep the theme of ghosts and evil spirits but believe it only happens to people who have done something bad. Irwin (1993, see A2 Level Psychology page 668) has found many crosscultural variations in paranormal belief. The Paranormal Belief Scale was standardised on Louisiana university students; in comparison to their beliefs, Finnish students report lower belief scores for witchcraft and superstitions but higher on extraordinary life forms. A similar pattern of low belief in witchcraft and superstitions was found in a sample of Polish students, who instead had stronger beliefs in psi (e.g. ESP and PK). Finally, Australian students had stronger beliefs in spiritualism and pre-cognition. In a more recent study, Belanti, Perera, and Jagadheesan (2008, see A2 Level Psychology page 668) examined near-death experiences in the Mapuche, Hawaii, Israel, Thailand, India, and many African regions and found the content of these reflected the cultural experiences, religion, and education of the different cultures. THE PSYCHOLOGY OF DECEPTION AND SELF-DECEPTION, SUPERSTITION, AND COINCIDENCE Deception RESEARCH EVIDENCE INTO DECEPTION The cases of scientific fraud covered previously are examples of deception. Wiseman (2001, see A2 Level Psychology page 670) notes that some faith healers assure people that they never accept money for their services to show that there is no motive to deceive. In cases like this, though, people often do pay. People may deceive to simply have some fun! This has been used to explain why two women, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, deceived the world for 66 years with their Cottingley Fairies photographs, which were eventually revealed to be cut-outs fastened to the ground with hat pins! Wiseman (2001, see A2 Level Psychology page 670) highlights that the simple use of body language and the positioning of hands, eye contact, etc. can essentially “make” an observer look one way so that trickery can happen undetected. A very unusual case of deception is reported by Randi (1982, see A2 Level Psychology page 670). This involved psychic surgery being used with great success. However, when he analysed the removed tissue he found that the blood sample was from a cow and that the supposed tumour was in fact chicken intestine. When confronted with the evidence, the psychic surgeon reported that it is a well-known fact that, during the procedure, supernatural forces change the tumour into something else once it has been removed from the body. Self-deception Self-deception is when we mislead ourselves to accept as true what is most likely false. Irwin (2002, see A2 Level Psychology page 671) suggests that many psychologists agree self-deception to be the acceptance of a belief in a self-serving way by people who have a motivation to believe in whatever is under investigation. RESEARCH EVIDENCE INTO SELF-DECEPTION Irwin investigated whether there was a relationship between self-deception and belief in paranormal activity in a group of students. Thirty Australian university students completed a range of questionnaires including the SelfDeception Questionnaire and the Revised Paranormal Belief Scale. From the latter, a participant was given two scores: a Traditional Paranormal Belief (TPB) score, which looked at belief in witchcraft, the devil, etc., and a New Age Philosophy (NAP) score, which looked at belief in parapsychology, reincarnation, and astrology. The results showed that TPB scores did not correlate with self-deception but that NAP scores did. That is, beliefs involving NAP are related to self-deception. However, not in the expected direction as belief in NAP was related to low levels of self-deception! EVALUATION OF RESEARCH INTO DECEPTION AND SELF-DECEPTION Difficult to study. Deception and self-deception are difficult to study due to their very nature. How can you test how much someone is trying to deceive you if they are successfully using deception? Cause and effect. The correlational design of Irwin’s research on selfdeception means that cause and effect cannot be established so all it can show is that the two measures are related to each other. Sample bias. The small size of the sample considerably limits generalisability. Superstition Superstition is defined as a belief or notion that is not based on reason or knowledge that highlights the “significance” of some behaviour to the individual. RESEARCH EVIDENCE INTO SUPERSTITION Skinner’s theory of operant conditioning states that learning is based on the consequences of behaviour. In general terms, we are more likely to repeat a behaviour if it is positively reinforced and less likely to repeat a behaviour if it is punished. One of the main assumptions of behaviourism is that general laws govern all behaviour (e.g. rewards), irrespective of species. Therefore, Skinner (1948, see A2 Level Psychology page 672) studied superstition in pigeons. Eight hungry pigeons were placed in their own Skinner boxes for just a few minutes per day, where they received food pellets every 15 seconds. This procedure lasted for several days and towards the end of this, the length of time between each delivery of pellets increased. Six of the eight pigeons began to show strangely repetitive behaviour in between the delivery of food pellets. These included head tossing, pendulum-type swinging of the head, hopping, and turning in an anti-clockwise circle. These behaviours had not been seen prior to the study and they were not performed once the food was presented to them. Thus, Skinner concluded that these behaviours are a form of superstition—the pigeons perform them as if the delivery of food depended on them doing it. Thus, superstitions develop when we learn that behaving in a certain way will be rewarded. This is a form of maladaptive learning because, in reality, the behaviour has nothing to do with the reward. EVALUATION OF RESEARCH INTO SUPERSTITION Experimental support. This approach to explaining superstitions has experimental evidence from Skinner’s work with pigeons to suggest that “random” rewarding leads to such a notion. Rewards are not always clear. Walking under a ladder or not stepping on cracks in the pavement rarely leads to an observable reward (such as with the pigeons getting food). Hence, it is not a complete explanation. On the other hand, behaviourists would be just as quick to point out that the reward for not walking under a ladder has simply not been identified yet and at some point one will be found. Another behavioural explanation would be the superstitious behaviour acts as a negative reinforce because anxiety is relieved by the superstitious behaviour, e.g. touching wood. Extrapolation. The behaviourist assumption that there are general laws of behaviour, which means that findings can be generalised to humans, can be criticised because there are qualitative as well as quantitative differences between humans and animals. For example, the much greater use of cognition in humans that questions how well the findings would generalise. Ignores cognition. Behaviourism ignores cognition because it is not observable or measurable, which is a significant limitation, because faulty cognitive processing may well account for superstition as the following theory suggests. Perceptual and memory errors RESEARCH EVIDENCE INTO PERCEPTUAL AND MEMORY ERRORS Jahoda (1969, see A2 Level Psychology page 672) suggests that superstitions are formed because of errors or faults in our perceptual and memory systems. For example, “selective forgetting” means we remember only superstition-confirming thoughts and behaviours. Lehmann’s (1898, see A2 Level Psychology page 672) study of séances supports the fact there can be errors in our perceptual and memory systems. The participants were asked to pick a line from a book. Lehmann then organised the séance so that there was a blackboard just underneath a red light with some unintelligible writing on it. The light was used because it is very difficult to observe much under this light, so anything that might be seen by a person at a séance would be an error in encoding and processing of information. Participants identified the unintelligible writing as the line they had chosen and so errors were confirmed. EVALUATION OF RESEARCH INTO PERCEPTUAL AND MEMORY ERRORS Artificiality of the research means problems with demand characteristics. The research set-up of a blackboard just underneath a red light is highly artificial and so may have cued the participants. Thus, demand characteristics, i.e. giving the researcher the findings being sought, may better explain these results than genuine errors in processing. The questionable validity of the study limits the support it provides for this explanation. Self-deception may be more valid. The possibility of a message just for the participants could have played into their self-importance and so they may have deceived themselves that the message was the line from the book they had chosen. Therefore self-deception may explain the findings rather that errors in processing and memory. Superstitions and the unconscious RESEARCH EVIDENCE INTO SUPERSTITIONS AND THE UNCONSCIOUS Freud (1901, see A2 Level Psychology page 673) explains superstitions through unconscious mechanisms. Unconscious fears and desires drive our behaviour. Freud believed that superstitions are a form of projection whereby the threats from these unconscious thoughts are dealt with by attaching them to things in the outside world. One of Freud’s examples starts with a person having a cruel thought about someone they care a lot about. This causes guilt and an expectation of punishment. This hidden conflict manifests in the conscious as a superstition that misfortune can be avoided if a particular set of behavioural patterns are stuck to. EVALUATION OF RESEARCH INTO SUPERSTITIONS AND THE UNCONSCIOUS Unverifiable and unfalsifiable. The unconscious cannot be tested; it is extremely difficult to operationalise (measure) the unconscious or how much anxiety is there and so Freud’s theory cannot be verified or falsified. How can we know that our anxiety is manifested in Freud’s theory as superstitious? It is just a theory as evidence is very limited: without such evidence we cannot establish if it has any truth but nor can we reject it as invalid. Lacks scientific validity. The fact that Freud’s ideas cannot be falsified means that it fails to meet this criterion proposed by Popper as a necessary requirement of science. This means that Freud’s work can be considered to lack scientific validity. Contemporary ideas and research on superstition Contemporary research has expanded on early work into faulty cognitive processing. RESEARCH EVIDENCE Lindemann and Arnio (2006, see A2 Level Psychology page 674) categorised participants into intuitive thinkers who tend to “trust their hunches”, and therefore use little reasoning, and analytical thinkers who tend to “have explainable reasons for decisions”. 239 Finnish volunteers completed a battery of questionnaires aimed to test their superstitious beliefs, analytical thinking, and intuitive thinking. Roughly half of the sample were superstitious and the other half sceptics. The findings clearly showed that the superstitious participants relied much more on intuitive thinking than the sceptics and much less on analytical thinking in general decision making. Lindemann and Arnio concluded that superstition can be explained using dual-coding processes. The dualprocessing refers to the fact we all process intuitively and analytically it is just that in superstitious people they process more intuitively when it comes to strange phenomena. EVALUATION Cause and effect. The argument here could be one of cause and effect. Thus, we cannot be sure if general thinking causes a person to be superstitious or if their general thinking is an effect of their superstition. Self-report criticisms. Questionnaires may not be the best method to test out processing as we may not have full conscious awareness of the processes used. Instead, the general population should be sampled to make the findings more representative. Reductionism. The classification of the groups into superstitious versus sceptics is, like any classification, oversimplified as this does not account well for individual variation. Coincidence Psychologists are obviously interested in coincidences because many anomalistic experiences are based on “strange occurrences”. But how many are simply coincidences that can be explained by the laws of probability? So if coincidence has the probability of occurring to every one in one million people per day, and the UK has a population of 61 million then 61 coincidences should happen per day, e.g. somebody ringing you just as you are thinking about them could lead you to thinking you have pre-cognitive power. Many of these may be seen as being anomalistic in nature when it is simply what should happen by chance! Coincidence and belief in paranormal activity Blackmore and Troscianko (1985, see A2 Level Psychology page 676) conducted a classic study into the link between belief in the paranormal and coincidences and probability. They ran a series of experiments testing out the beliefs and probability judgements of sheep (believers in psi) and goats (non-believers in psi). They found that sheep are more likely to see a coincidence as being something “out of the ordinary” because they are more likely to overlook probability explanations for events in favour of anomalistic explanations. The sample for this research was 50 schoolgirls so it lacks generalisability. However, a second sample of 100 volunteers (aged 12–67) were tested on their understanding of probability (results happening by chance) and the same results were found, that is “sheep” overlook probability and prefer “coincidence” as an explanation. So what does this mean? Overall, it can be clearly seen that cognitive, personality, and biological factors affect people’s anomalistic experiences and beliefs, which need to be taken into account when conducting research. Generally, it would appear that individuals who experience some form of trauma in childhood are more likely to believe in things paranormal. This appears to be linked to lack of control in childhood and a consequent fear of lack of control in adulthood accompanied by a belief in the paranormal as a way of coping with lack of control. Social loneliness and proneness to fantasy also appear to be linked to beliefs, whereas coping strategies and attachment style do not. Research into different cultures’ interpretations of sleep paralysis and near-death experience shows that anomalistic phenomena are shaped by culture. There are many examples of deception in anomalistic research, however, testing whether self-deception exists has been less clear as neither Traditional Paranormal Belief (TPB) nor New Age Philosophy (NAP) correlate with high levels of self-deception. Superstition has been explained using a number of approaches—learning, psychodynamic, and errors in perceptual and cognitive processing. However, superstition is difficult to research: the role of unconscious processes cannot be verified or falsified and we cannot be sure if general thinking causes a person to be superstitious or if their general thinking is an effect of their superstition. Research into coincidence suggests that those who believe in parapsychology are more likely to accept coincidence as an explanation and overlook the probability that the event is due to chance. Over to you 1. (a) Discuss cognitive factors underlying paranormal beliefs. (10 marks) (b) Discuss the functions of paranormal and related beliefs, including their cultural significance. (15 marks) 2. (a) Outline biological factors underlying anomalous experience. (5 marks) (b) Discuss the psychology of deception, self-deception, superstition, and/or coincidence in anomalous experience. (20 marks)