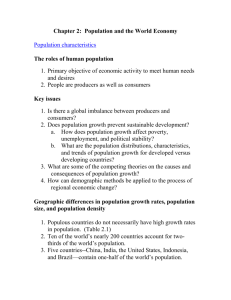

Chapter 6: Population and Consumption in Word

advertisement