CEPSA 2011, Vienna - Multilevel Politics: Intra- and Inter

advertisement

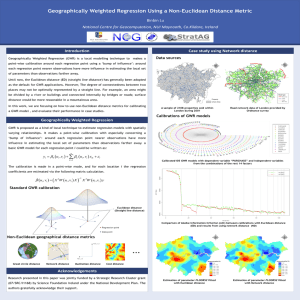

CEPSA 2011, Vienna - Multilevel Politics: Intra- and Inter-level Comparative Perspectives West and East: Still Mind the Gap? Aggregate Analysis of Electoral Behavior in Central Europe1 Petr Voda – Michal Pink First draft only for presentation at conference venue Abstract A series of changes has taken place in Central Europe after the fall of communism. Some of these changes have been driven by the increased influence and relevance of a multilevel government, the highest level in the hierarchy being Brussels and the lowest, the closest municipality. A question remains as to whether these changes have been of a uniform nature, or whether they have influenced different states – and even different locations within the same state – in different ways. This paper focuses on patterns of electoral behavior in terms of the spatial distribution of election results and the impact of social structure. It asks whether these patterns have become more similar in the Central European region. The basic hypothesis is that the influence of socioeconomic characteristics is becoming ever more similar with the continuing integration of Central Europe. The first phase of the analysis will be quantitative in nature. We employ ordinary least squares regression and geographical weighted regression, using data from elections and censuses, to describe similarities and differences in the influence of electoral behavior determinants among countries (Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary), as well as the development of these factors. The second phase studies the alignment of results in terms of important dates in the integration process. Introduction The countries of the EU have experienced different histories over the last half-century. A key distinction dividing members is between those countries in the East which were under nondemocratic communist regimes and those of the West, where development was democratic. Countries on both sides of this division lie side-by-side in Central Europe, with the dividing line running through Germany, between Germany and the Czech Republic, Austria and the Czech Republic and Austria and Slovakia, Hungary and Slovenia. At times in the past, these countries have been very close – almost identical in many respects – as well as very different, as was the case from the 1950s until the late 1980s. Since that time, they have once again grown closer and likely more similar, as well. Over the last 20 years, many new actors have appeared on the political stage in these countries, particularly on the eastern side of the dividing line. Numerous integration projects have taken place in the region. The most influential would be the coming of the EU. Austria acceded in 1995. Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia and Hungary became part of the EU in 2004, after a lengthy entrance procedure. These milestones have played an 1 This text has been prepared as part of postdoctoral grant supported by the GACR—Political Regionalism in the Czech and Slovak Republics and Changes in Voting Maps 1993–2010, No. 407/09/P042. 1 important role in changing the politics, policies and polities of countries in the region. European integration are obviously very important for changing politics, policies as well as polities of all these countries (see Carbone 2010, Goetz, Hix 2001, KriegerBoden, Morgenroth, Petrakos 2008 etc.). But how deep are these changes? A lot of articles suppose some change in manifestos of parties. However, we do not know, how affected voters are. Our focus will not be on parties, policies or actors, but rather on the relationship between parties and their voters in elections. We make the following assumptions: just after the revolutions of 1989, Western and Eastern countries differed greatly from each other. In the West, political parties obtained votes from different social groups and made different policies. Over time, though, with capitalism taking hold, increasing wages and unemployment and, of course, with the EU integration process, both societies and politics in the East have changed. The question is: how have connections between parties and society developed in Western and Central Europe? The answer is not easy to find. Data from several sources and multivariate statistical methods will be used to provide one. Manifestoes, party activities, governments and parliamentary bodies will not be the focus; we will instead concentrate exclusively on the election results for relevant parties in general elections. There are several potential ways to work with these results. We will use data for the micro-regional level and employ "traditional" OLS regression. To address problems associated with OLS regression in studying nonstationary relationships, geographically weighted regression techniques will be used to take special notice of the manner in which the relationship between election results and certain causal factors varies across space (see Kavanagh 2006). Regression analysis will be used to make comparisons. The focus will be on determining whether parties within the same family but in differing countries show similar support patterns and whether the changes these patterns undergo are similar in nature. It is here that a key issue arises. In progressing from counting GWR and interpreting the results to making comparisons between countries, we suddenly have only a highly restricted space to control for. Thus it is not certain whether the changes observed have truly arisen from the causes theorized, or whether another factor may be impacting the development of electoral behavior in the countries selected. To determine an answer to the second question, Rokkan’s theory of cleavages will be applied. There are for original cleavages: urban vs. rural, center vs. periphery, owners vs. employees and church vs. state (Lipset, Rokkan 1967: 9-23). Each of these cleavages could give rise to a 2 party. The four cleavages are based upon the structure of society during the 19th century, when parties arose around conflicts between the aims of the urban and rural population, between owners and employees, between religious and secular individuals and between inhabitants of the center and the periphery. Particular sides in the conflict have changed over the course of the last century, but its bases likely remain the same. Some people are more motivated to vote for certain parties as opposed to others, because their social status differs (Evans 2004:42-68). For finding an answer to the question Rokkan’s theory of cleavages will be applied. There are four original cleavages: urban – rural, center – periphery, owners – employees and church – state (Lipset, Rokkan 1967: 9-23). On each of these cleavages some party could exist. These four cleavages are based on the structure of society in 19th century, when parties arose around conflicts between aims of urban a rural population, between owners and employees, between religious and secular and between inhabitants of the center and periphery. These sides of conflict changed throughout the last century but the bases are probably still the same. Some people are more motivated to vote certain parties than others because they have a different social status (Evans 2004: 42-68). Several articles dealing with electoral behavior in early 90’s in post-communist countries assume the Rokkan’s theory inappropriate in context of new democracies because of historical and geographical bases of this theory as well as specific context of states after falling communist regimes. Dalton (2000: 925-926) notices that emerging party systems are unlikely to be based on stable group-based cleavages, especially when the democratic transition happened rapidly as in Eastern Europe. Also new electorates are unlikely to hold long-term party attachments that might guide their behavior. That is the reason, why the patterns of electoral choice in new democracies are more involved by short-term factors like candidate images and issue positions. Several studies also exist concerning the impact of European integration on electoral behavior. Gabel (2001: 52-54) sees research on the topic focused above all on the question of issue voting (see de Vries 2007). He notes the example of Great Britain, in which EU issues have created new electoral cleavages, and examines the importance of European monetary policy in economics-based voting behavior. Tillman (2008) also addresses the impact of attitudes towards European economic issues on voting behavior and national politics. Such an approach imposes a number of limitations, especially in the comparative dimension of analysis. The data itself may be hard, but changing conditions and modified meanings over time and through space make it function rather more like soft data. The fact that a vote was 3 cast for certain party in certain elections in certain country does not entitle us to compare the meaning of the vote with one cast for similar party in election in another country. The meaning may be better described by applying more general concepts. Thus the Rokkan’s theory and Bayme’s classification of parties are used. But this will only mitigate, not eliminate the limitations. These concepts may help us to locate cases in which the level of comparability is higher than in others. Other way to provide comparability is to select countries on an areal basis. We chose Austria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary with logic of Mill’s method of most similar cases. All countries have similar history and cultural bases. The countries share common frontiers, allowing the degree to which societies are contained within the geographic area of the country to be determined, as well as what development is like in the Western and Eastern blocs. These countries are also similar in terms of their political regimes. Each country has a parliamentary democracy. The only distinction lies in the unitary character of the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary; Austria, by contrast, may be described as a federal state. All states, however, have autonomous regional governmental elections, meaning the parliamentary elections have almost the same meaning and sense in all of these countries. The party systems of all the countries under consideration are fairly close. All of them are pluralistic as regards the number of parties and are moderate as regards type under Sartori's classification. The only exception is the Czech system, which is assumed to be semi-polarized (Strmiska 2005). However, individual systems differ in time and space in terms of the number of relevant parties. This probably forms the fundamental limitation on our conclusions and the research as a whole. This becomes even more critical when we focus on development. It is obvious that the party system has changed markedly since 1990, but it may be less obvious that the parties themselves have also changed. There is no party in which the same personalities are saying the same things as was said in 1990. Questions related to party systems are important because the nature of a party’s system creates possibilities for voters. From our perspective, the different structure of party systems might result in different bases of electoral support for the parties. There is a real threat that the composition of a party's electoral base will not adequately represent the party's ideological profile. This depends upon the voters' ability to make decisions concerning their vote. Their votes may be influenced by several other factors described by psychological models and by issue-based models, for example: sympathy for a particular candidate, identification with a party, or agreement with the party's attitude on some key issue. All of these factors taken together cannot be captured in a single article. In this 4 case, then, the research problem has been simplified to include only the influence of social stratification on election results. Several methodological issues arise in terms of the comparability of electoral systems as well as party systems. Chief among these are the Hungarian elections, which take place under the rules of a mixed system (see Sedo 2009). Collections in the other countries (Austria, the Czech Republic and Slovakia) use a proportional system. The problem arises because no election results are available for areas smaller than electoral districts. Thus, results from the majority party must be used. This represents a huge limitation in making comparisons, since the conditions of the majority system are quite different to those in the proportional system. In particular, there are strong incentives for strategic voting. Smaller parties are heavily impacted, because there is almost no point in voting for them in a majority system (see Abramson, et al. 2010). Hungary will nevertheless remain in the analysis but these potential limitations must be borne in mind. Data The research question makes clear that data is needed concerning elections and societal factors. The data used in this analysis derive from two sources. Electoral results for each general election are taken from the central election commissions of the countries selected. These election results will serve as the dependent variable for the first portion of the study. The dates at which the elections were held are suitable for purposes of comparison. Every country involved had elections in 1990, 2002 and 2006. There were elections in three countries in 1994, 1998 and 2010 (see Table 1). Temporal context, then, presents virtually no problem. Table 1: General Elections in Central Europe in 1990 - 2010 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2001 2002 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Austria Czech Republic Hungary Slovakia Source: Parties and Elections Societal data is derived from censuses that took place in 1991 and 2001 in all selected countries. Independent variables have been selected using a multi-step process. First, cleavage indicators under Rokkan’s theory are selected. All independent variables have some relationship to a particular cleavage. The following variables have been selected: proportion of self-employed persons, proportion of highly educated persons and the unemployment rate 5 as indicators for the economic cleavage; proportion of agricultural workers and urbanization rate as indicators for the urban-rural cleavage; ethnic divisions in society for the centerperiphery cleavage; and for the church-state cleavage, the proportion of Christians. In the second step, variables with no comparable data and variables lacking data for all countries and censuses are eliminated. This leaves only the proportion of Christians, agricultural workers, persons with a university education, unemployment and the rate of urbanization. Finally, all variables demonstrating high global or local multicollinearity are eliminated. The resulting list of variables is as follows: proportion of Christians, proportion of agricultural workers and number of highly educated persons. All data are tied to regional NUTS4 units, except for data relating to Hungary. The units concerned are called ORP in the Czech Republic (Municipalities with Extended Powers), Okres in Slovakia and Politische Bezirke in Austria. Results for Hungarian general elections were available only for electoral districts, while census data was available for different census regions. Data for the analysis was calculated using overlapping areas. Table 2 shows the basic characteristics of regions. The number of units is also number of cases of further regression analyses. Austrian, Hungarian and Slovakian units are very similar in average number of inhabitants as well as average area. Czech micro-regions are smaller. Table 2: Regional Units of Analysis Number Averege number of units of inhabitants Average area (km2) Austria 121 68264,46 693,15 Czech Republic 206 51129,95 349,51 Slovakia 79 68305,92 620,70 Hungary 156 64012,82 596,35 Source: own calculation, based on Statistik Austria, ČSÚ, SŠÚ and valastazs.hu Method The focus is on relations between society and political parties. This means we require indicators which tell something about the state of society, indicators concerning political parties and a method which allows us to put the two together. Because we wish to inquire into the relationship between election results and the social characteristics of particular localities, we need a method capable of handling a large number of variables. For normally distributed data, the best option is regression analysis. The most important results of the analysis are 6 contained in the value of (adjusted) R-squared and the beta coefficients. Adjusted R-squared2 shows how much variability in the dependent variable is explained by variability in the independent variables (Field 2009: 206-207) and indicates how well the model fits. The Beta coefficient shows the explanatory power of particular independent variables. Higher values mean higher dependence of the dependent variable on that independent variable. There is no need to employ inferential statistics, since the entire population of regional units is used for the calculations (see Soukup, Rabušic 2007). Because all used data have spatial attributes, spatially weighted regression should be a superior technique because it allows for spatial autocorrelation. Some events are more likely to take place because they are happening globally and are not due to local conditions. This tends to invalidate the assumed independence of error terms, creating a potential challenge for classical statistical inference (Fotheringham 2008: 243). Fotheringham (2002: 27) identifies several advantages of the method. It is based on the traditional regression framework with which most readers will be familiar and it incorporates local spatial relationships into the regression framework in an intuitive and explicit manner. Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) departs from the traditional assumption that all causes have the same response at every location. Instead, it takes spatial dependency into count. The result is not only a single number for each parameter estimated, but a table showing different values for each parameter at distinct locations. In addition to the overall regression, GWR takes into account the effects of independent explanatory variables on the dependent variable. The results of a GWR analysis are similar to those of OLS regression. Model fit is measured by the sum of the squared residuals. The smaller the value, the better the GWR model fits the observed data. Goodness of fit is measured by R-squared, the same as in OLS described above. There are several differences between GWR and OLS. The effective number of degrees of freedom is a function of bandwidth, so the adjustment may be quite marked compared to a global model like OLS. The effective number reflects a tradeoff between the variance of the fitted values and the bias in the coefficient estimates and is related to the choice of bandwidth. In addition to regression residuals, the Output feature class includes fields for condition number indicating multicollineatity, local R-squared, local explanatory variable coefficients and coefficient Standard Errors (Fotheringham 2002). 2 Calculations for the adjusted R-squared value normalize the numerator and denominator by their degrees of freedom. This has the effect of compensating for the number of variables in a model, and consequently, the Adjusted R2 value smaller than the R2 value. 7 Outcomes of general elections in 1990 - 2010 Before turning to the results of the analysis, let us briefly describe the subject matter of the analysis: election turnout and election results in all elections to the lower chamber of national parliaments. The figures are limited to results for parties occupying a relevant place in at least three elections. Outcomes for parliamentary elections in Austria are highly stable throughout the period of the study. Figure 1: Electoral Turnout and Results of General Elections in Austria in 1990 - 2010 100 90 80 70 SPÖ 60 ÖVP 50 GRÜNE 40 FPÖ 30 Turnout 20 10 0 1990 1994 1995 1999 2002 2006 2008 Source: Parties and Elections (http://parties-and-elections.de/austria.html) Electoral turnout is very high, around 80% in all cases (see Figure 1). The Social Democratic Party of Austria (SPÖ) is the highest vote getter in every election. The only exception to this comes in 2002, when the vote share of the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP) increased. These two parties form the chief poles of electoral competition in every election during the period of study. During the same period, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) dropped 17%. The final party of relevance is the Green Party. In the two latest elections, a new party, BZÖ, arises to challenge the system. In the Czech Republic, election outcomes are not as stable as they are in Austria. There has been significant change since 1990. Voter turnout decreased from 96% in 1990 to 62% in 2010 (see Figure 2). Party changes have also taken place. The Czech Social Democratic Party (CSSD) and the Civic Democratic Party (ODS) were the chief players after the initial elections, when competition primarily focused on the Civic Forum3 and the Communist Party 3 The civic Forum was broad movement. After elections in 1990 started disintegration. One of successor, and the most important one, is th Civic Democratic Party (see Strmiska 2005). 8 of Czechoslovakia. Only two other parties present at that time are still part of the system in addition to CSSD and ODS. They are the Communist Party and the Christian-Democratic Union. There is some space for liberal parties, which are very unstable in the Czech Republic. The Civic Democratic Union (ODA), Union of Freedom (US) and TOP09 may all be fairly described as liberal as, with some reservations, may be the Green Party. Figure 2: Electoral Turnout and Results of General Elections in the Czech Republic in 1990 – 2010, 100.00 90.00 80.00 70.00 ODS 60.00 CSSD 50.00 KSCM 40.00 KDU-CSL 30.00 Turnout 20.00 10.00 0.00 1990 1992 1996 1998 2002 2006 2010 Source: Parties and Elections (http://parties-and-elections.de/czechrepublic.html) Elections in Hungary share features with the Czech elections. The party system was simplified in the 1990s and voter turnout has also been unstable. In the case of Hungary, however, voter turnout began at a relatively low figure of "only" 65% in 1990, decreasing to 50% by 2002, then beginning to grow once again (see Figure 3). Competition between the Hungarian Socialist Party (MSZP) and Hungarian Civic Union Fidesz was the focal point of elections, but in the most recent elections in 2010, MSZP’s vote share decreased substantially. MDF and the Nationalist party MIEP remain in the system, the latter renamed Jobbik prior to the most recent elections. Figure 3: Electoral Turnout and Results of General Elections in Hungary in 1990 – 2010 9 100 90 80 70 MSZP 60 FIDESZ 50 SZDSZ 40 MDF 30 MIEP 20 Turnout 10 0 1990 1994 1998 2002 2006 2010 Source: Parties and Elections (http://parties-and-elections.de/hungary.html) Figure 4: Electoral Turnout and Results of General Elections in Slovakia in 1990 - 2010 100 90 80 SDL/SV/SMER-SD 70 DS/SDKU-DS 60 SNS 50 MKP/Híd 40 LS-HZDS 30 KDH 20 Turnout 10 0 1990 1992 1994 1998 2002 2006 2010 Source: Parties and Elections (http://parties-and-elections.de/slovakia.html) The most complicated party system is that of Slovakia, which has registered more change than any other of the selected countries (see Figure 4). Many voters have ceased voting. Voter turnout was 95% in 1990, but only 55% in 2006. During the 1990s, the populist People's Party – Movement for a Democratic Slovakia (HZDS) was the leader. Recent elections have seen Direction – Social Democracy (SMER) come to the fore. The second strongest party at present is the Slovak Democratic and Christian Union (SDKU). The system also includes representatives of the Christian-Democratic, nationalist and liberal party traditions, as well as parties representing ethnic minorities. 10 The figures and information shown above reveal several similarities. Competition for voters mainly takes place between two parties. In all cases, one of these is Social Democratic and the other (liberal) conservative. The only exception is Slovakia, to a certain extent. There are many parties in every election. One of them normally obtains significantly more votes than the competition. Voter turnout is much higher and more stable in Austria than in the other countries, but was also quite high in the Czech Republic and Slovakia during the early 1990s. These countries have since witnessed a marked drop. For purposes of comparison, it is useful to group parties into similar cases. For this purpose, Bayme’s concept of political party families (Bayme 1985) or Lewis's modification for Central-Eastern Europe (Lewis 2000) may be applicable. Both classifications have been criticized in terms of their appropriateness for the post-communist context (Fiala, Strmiska 2004:13-25). They have been judged as being static, generic and West-centric in nature. But no alternative solution has been offered, thus we will employ Bayme’s theory, adding to it an "Others" category (see Table 1). Table 1: Parties According to Bayme’s Classification in Selected Countries in 1990-2010 Communist s Austria Czech Rep Hungar y Slovaki a KPÖ KSCM KSS, ZRS SocialDemocr ats SPÖ CSSD Green Liber al Conservativ e G SZ ÖVP ODS MSZP LMP Smer, SDĽ SZ FPÖ ODA, US, TOP0 9 SDZS Z SaS, ANO Christia n-Dem Extrem e Right KDUČSL BZÖ SPRRSČ Fidesz MDF SDKÚ KDH MIEP, Jobbik SNS Other Minorities VV, LSU HSD-SMS VPN, LSHZDS Híd, MDK Source: Strmiska et al. (2005) There are about 40 relevant parties according to Sartori's rules in at least in 9 categories. But only two party families are present in every country at every time. These are the Social Democrats and the Conservatives4. Electoral support for parties of these two families will be analyzed. Analysis This section will discuss the results of ordinary least squares regression and geographically weighted regression. The analyses seek to answer the question of whether the electoral base of parties in Central-Eastern Europe have become more similar to those of their counterparts in 4 The precise classification is not neccesessary to achieve the goal of this text. It is only way to better specify the conditions of comparison. 11 Central-Western Europe. Voter turnout and results for social democratic and conservative parties are explained by several indicators of social structure: the proportion of Christians in the society, the proportion of agricultural workers in the economically active population and the proportion of people with a higher education in the population 15 years of age or older. Electoral turnout The dependence of voter turnout on social structure changes over time in each country, always with a pattern unique to that country: turnout in Hungary increases, turnout in Austria and Slovakia decreases, and turnout in the Czech Republic fluctuates. The strength of the relationship differs, as well. The model can account for three-quarters of the variance in voter turnout in Austria, around 30-50% of variance in Hungary and the Czech Republic and only 10-20% of variance in Slovakia. The spatial character of the dependency also differs. In Austria OLS provides results which are almost identical to GWR, but this is not true for the Czech Republic, Hungary or Slovakia. In these latter countries, the effect of the independent variables differs in different locations. Table 2: Adjusted R-squared of OLS regression and GWR for Electoral Turnout Austria Czech Republic Slovakia Hungary OLS GWR OLS OLS OLS GWR OLS GWR 1990 0,76 0,77 0,31 0,37 0,21 0,30 0,36 0,66 2002 0,45 0,43 0,46 0,52 0,12 0,26 0,57 0,66 2006 0,51 0,51 0,43 0,50 0,11 0,46 0,56 0,61 Social Democrats This section analyzes results for the Social Democratic Party of Austria, the Czech Social Democratic Party, the Hungarian Socialist Party and the Slovak parties Democratic Left and Direction – Social Democracy. The model clearly loses explanatory power for Austria. The OLS regression model explained 55% of variance in 1990, but only 20% of variance in 2008. The manner in which the independent variables affect election results has also changed. Rsquared is almost identical for GWR and OLS in 1990. But by 2010, R-squared under the GWR model is almost twice as high as that of OLS, indicating that identical variables now vary in their influence depending upon location. Table 3: Results of OLS regression for SPÖ 12 OLS GWR 1990 0,55 0,66 1994 0,42 0,70 1999 0,21 0,38 2002 0,25 0,41 2006 0,21 0,39 2008 0,19 0,38 The Czech Social Democratic Party saw a change in support between the 1992 and 1996 elections. Since that time, there has been almost no dependency relationship involving CSSD’s election results as indicated by OLS regression. The GWR shows another picture. CSSD’s results show a higher level of dependency, since 1992 (with exception 2002) constant over time, on the independent variable set. Table 4: Results of OLS regression for ČSSD OLS GWR 1990 0,57 0,63 1992 0,39 0,44 1996 0,11 0,30 1998 0,12 0,33 2002 0,02 0,18 2006 0,16 0,36 2010 0,18 0,36 Both OLS and GWR reveal almost no dependency on religiosity or rural and educational characteristics for MSZP’s results. With the decline of support for MSZP which occurred in 2010, the party's support became at least partially dependent upon these variables. Table 5: Results of OLS regression for MSZP 1990 0,08 0,11 OLS GWR 1994 0,12 0,18 1998 0,05 0,14 2002 0,12 0,24 2006 0,11 0,21 2010 0,28 0,33 Results from Slovakia must take into account the existence of four different social democratic parties. All of them (except the Common Choice coalition in 1994) showed a high level of independence from the social structure indicators, most easily visible from 2002, when SMER first participated in elections. Table 6: Results of OLS regression for SD, SV, SDĽ and SMER OLS GWR 1990 0,08 0,46 1992 0,07 0,58 1994 0,34 0,51 1998 0,14 0,29 2002 -0,01 0,05 2006 0,09 0,24 2010 0,07 0,20 As regards social democratic parties, parties in the East follow common sense in having a low dependency for social democratic results on our selected independent variables. The only exception is the Czech Social Democratic Party in the early 1990s. Once again, there is an obvious drop in the explanatory power of the model when it comes to Austria. Conservative Parties This final section deals with results concerning the electoral base of conservative parties. 13 Explanatory power for the model is almost the same for the election results of ÖVP as for SPÖ. Once again, there is a significant drop in the model's explanatory power. The OLS regression model accounts for around 70% of variance in the early 1990s, but by 2008 can explain only 45%. In contrast to the results for SPÖ, GWR and OLS models come out almost the same and there is no significant change, as was the case with SPÖ. Table 7: Results of OLS regression for ÖVP OLS GWR 1990 0,68 0,71 1994 0,65 0,70 1999 0,48 0,51 2002 0,45 0,48 2006 0,47 0,50 2008 0,46 0,48 Election results for ODS depend less on the selected variables than do the results for ÖVP. This may be due to the civic nature of the party; ÖVP is a partially Christian-Democratic party. But the dependence on social structure characteristics is reversed. The explanatory power of the OLS regression increases from 25% in 1992 to 47% in 2006, before falling again in 2010. The GWR model, however, shows a higher dependency, indicating high spatial autocorrelation in the OLS regression estimates. Obviously, it is less important in 2010 than in 1992. Table 8: Results of OLS regression for ODS OLS GWR 1990 0,24 0,41 1992 0,25 0,43 1996 0,18 0,30 1998 0,41 0,55 2002 0,45 0,57 2006 0,47 0,59 2010 0,26 0,36 Election results for Fidesz are almost independent of the explanatory variables for all elections. In 1994 and 1998, there is perfect independence, with the GWR model showing very low values, as well. There is thus no dependency on the explanatory variables and no dependency on results in neighboring regions in the 1990s. Since 2002, however, there has been very little evidence of dependency for the selected indicators of social structure in OLS results, but somewhat greater values for the GWR results. Table 9: Results of OLS regression for Fidesz OLS GWR 1990 0,14 0,13 1994 0,00 0,03 1998 0,00 0,03 2002 0,23 0,39 2006 0,17 0,28 2010 0,15 0,33 Just as was the case for Social Democratic parties, there has been more than one conservative party in Slovakia active in the period since 1990. The role was played by the Democratic Party until 1994, by the Slovak Democratic Coalition in 1998 and, since 2002, has been played by the Slovak Democratic Christian Union. The 1990 results show great strength, 14 perhaps because of the uniqueness of the situation after the fall of the communist regime and the role of the civic movement Public Against Violence (VPN). These results, then, are similar to those in Austria and the Czech Republic, with the exception of the existence of different parties. The results for DS showed the highest level of dependence on our explanatory variables, those for SDK and SDKU less so, but the results of the latter parties are more dependent on those in neighboring regions than is the case for DS. Table 10: Results of OLS regression for DS, SDK and SDKÚ OLS GWR 1990 0,09 0,11 1992 0,64 0,68 1994 0,64 0,69 1998 0,35 0,53 2002 0,48 0,75 2006 0,44 0,70 2010 0,42 0,61 The results for ÖVP and the Slovak conservative parties are obviously highly dependent upon the independent variable because of the significant influence of religiosity present. The Czech Civic Democratic Party shows less dependence and Fidesz, none at all. Conclusions This text deals with trends of electoral behavior in West and East Central Europe. The texts from early 90’s mention the distinction between old and new European democracies. Analysis made in this contribution shows some differences at the starting point of this analysis. The electoral turnout and electoral results of Social Democrats and Conservatives were explained by several indicators of social structure suggested by Rokkan’s theory of cleavages (religiosity, proportion of agricultural workers and highly educated people) through OLS regression and geographically weighted regression. The results show that the explanatory power of model was high in early 90’s in Austria in the case of electoral turnout, social democrats even conservatives. On the other hand, it was significantly lower in case of electoral turnout and all Social democratic parties and Conservative parties in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary. While in Austria the explanatory power of both models is lower, their power increases in all countries in the East. This means that Austrian parties are becoming less and less dependent upon social groups, while their counterparts in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary are experiencing greater dependence. Some caution must be taken in interpreting the results for Hungary, since election outcomes in that country are based upon a majoritarian electoral 15 system. Thus, the answer on proposed question talks patterns visible at aggregate level became more and more similar. We found out something like unification of influence of social structure on electoral behavior, but we examined nothing about possible causes of this situation. Changes in party support and the party base behind these changes are probably not directly motivated by external factors like European integration. There is no meaningful change in explanatory power between 2002 and 2006, although the Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia entered into the EU between these two elections. Thus, the described trends seem to be rather independent on European integration. Also if the R-squared tends ever higher, electoral results are better explained by the selected variables than they are other variables (such as European integration). But European integration may function as an intervening variable, making the picture less clear than it would otherwise be. 16 Literature and Sources Electoral results: BM.I ‘Nationalratswahlen’ Available at: http://www.bmi.gv.at/cms/BMI_wahlen/nationalrat/start.aspx (Accessed on 30 September 2011). National Election Office (2010) ‘Parliamentary elections 2010’. Available at: http://www.valasztas.hu/en/parval2010/index.html (Accessed on 30 September 2011). ČSÚ (2010) ‘Volby do Poslanecké sněmovny Parlamentu České republiky’. Available at: http://www.volby.cz (Accessed on 30 September 2011). Parties and Elections, Available at: http://parties-and-elections.de (Accessed on 30 September 2011). Štatistický úrad Slovenskej republiky ‘Volebná štatistika’. Available at: http://portal.statistics.sk/showdoc.do?docid=4490 (Accessed on 30 September 2011). Vokscenter (2010) Available at: http://www.vokscentrum.hu/index.php (Accessed on 30 September 2011). Data: Štatistický úrad Slovenskej republiky ‘RegDat. Databáza regionalnej štatistiky’. Available at: http://px-web.statistics.sk/PXWebSlovak/index.htm (Accessed on 30 September 2011). Statistik Austria ‘Volkszahlung 2001’ Available at: http://www.statistik.at/web_de/statistiken/bevoelkerung/volkszaehlungen_registerzaehlungen/ index.html (Accessed on 30 September 2011). ČSÚ ‘Regiony, města, obce’. Available at: http://czso.cz/csu/redakce.nsf/i/regiony_mesta_obce_souhrn (Accessed on 30 September 2011). Központi Statisztikai Hivatal ‘Tájékoztatási adatbázis’. Available at: http://statinfo.ksh.hu/Statinfo/themeSelect or.jsp (Accessed on 30 September 2011). Diva GIS ‘Download data by country’. Available at http://www.diva-gis.org/gdata (Accessed on 30 September 2011). ESRI: ArcCR500 Literature: Abramson, Paul R., et al (2010) ‘Comparing Strategic Voting under FPTP and PR’, Available at http://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1007&context=renan (Accessed on 30 September 2011). Carbone, Maurizio (2010): ‘National politics and European integration: from the constitution to the Lisbon Treaty’. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. 17 De Vries, Catherine E. (2007). “Sleeping Giant: Fact or Fairytale? How European Integration Affects National Elections.” European Union Politics 8 (3): 363-385. Dalton, Russel, J. (2002) ‘Citizen Attitudes and Political Behavior’ Comparative Political studies 33 (6-7): 912-940. Evans, Geoffrey and Whitefield, Stephen (2000) ‘Explaining the formation of electoral cleavages in post–communist democracies’ in Klingemann, Hans-Dieter, Mochman, Ekkehard and Newton, Kenneth (eds) ‘Elections in Central and Eastern Europe: The First Wave’ Berlin: Sigma. Evans, Jocelyn. A. J. (2004) ‘Voters & Voting: An Introduction’. London: Sage Publications. Fiala, Petr and Strmiska, Maxmilián (2004) ‘Ideově-politické rodiny a politické strany v postkomunistických zemích střední a východní Evropy’, in: Fiala, Petr et al. (eds) Politické strany ve střední a východní Evropě. Brno: Masarykova univerzita. Field, Andy (2009) ‘Discovering Statistics Using SPSS (Introducing Statistical Methods)’. London: Sage Publications. Freedman, David A. (1999) ‘Ecological Inference and the Ecological Fallacy’. Available at http://www.stanford.edu/class/ed260/freedman549.pdf (Accessed on 30 September 2011). Fotheringham, Stewart and Rogerson, Peter A. (2009): ‘The SAGE Hanbook of Spatial Analysis. London’: SAGE. Fotheringham, Stewart (2002): ‘Geographical Weighted Regression’. Chichester: Willey. Gabel, Matthew (2001): ‘European Integration, Voter and National politics’. In Goetz, KlausH. and Hix, Simon (2001): ‘Europeanised politics?: European integration and national political system’. London: Routlege. Hendl, Jan (2006) ‘Přehled statistických metod zpracování dat. Analýza a metaanalýza dat’. Praha: Portál. Kavanagh, Adrian et al. (2006) ‘A Geographically Weighted Regression Analysis of General Election Turnout in the Republic of Ireland’.Paper presented to the Political Studies Association of Ireland Conference, University College Cork. http://www.psai.ie/conferences/papers2006/kavanagha1.pdf Krieger-Boden, Ch., Morgenroth, E. and Petrakos, G. (2008) ‘The Impact of European Integration on Regional Structural Change and Cohesion’. London: Routlege. Lipset, Saymour and Rokkan, Stein (1967): ‘Party systems and voter alignments: crossnational perspectives’. New York: Free press. Soukup, Petr and Rabušic, Ladislav (2007) ‚Několik poznámek k jedné obsesi českých sociálních věd, statistické významnosti‘, Sociologický časopis 43, 2: 379-395. 18 Strmiska, Maxmilián et al. (2005) ‘Politické strany moderní Evropy’. Praha: Portál. Šedo, Jakub (2009): ‘Volební systémy postkomunistických zemí’. Brno: CDK. Tillman, Erik (2008): ‘European Integration and Voting Behavior in the 2001 British General Election’. Prepared for presentation at the Workshop on the Politics of Change, June 13-14, 2008, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. http://www.unc.edu/euce/eusa2009/papers/tillman_03B.pdf Von Beyme, Klaus (1985) Political Parties in Western Democracies. Aldershot: Gower Press. 19