1 Terms of Reference

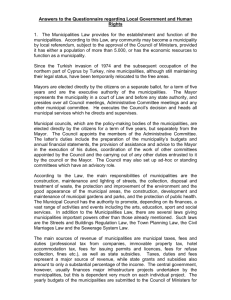

advertisement