IHS-Caries Risk Assessment

advertisement

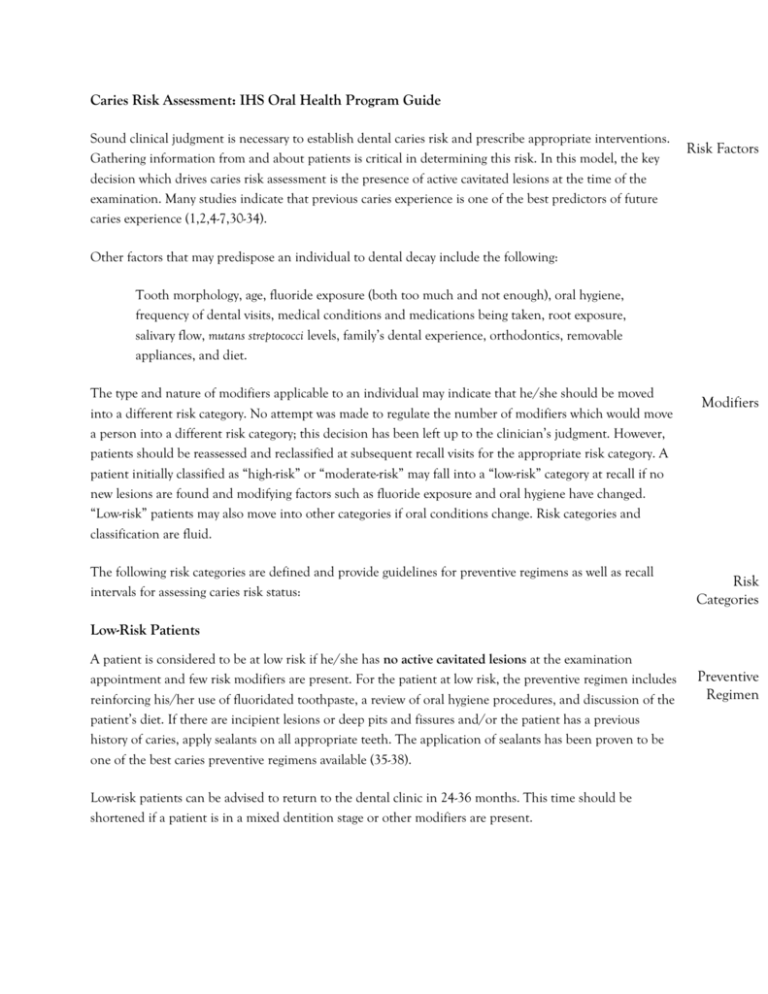

Caries Risk Assessment: IHS Oral Health Program Guide Sound clinical judgment is necessary to establish dental caries risk and prescribe appropriate interventions. Gathering information from and about patients is critical in determining this risk. In this model, the key decision which drives caries risk assessment is the presence of active cavitated lesions at the time of the examination. Many studies indicate that previous caries experience is one of the best predictors of future caries experience (1,2,4-7,30-34). Risk Factors Other factors that may predispose an individual to dental decay include the following: Tooth morphology, age, fluoride exposure (both too much and not enough), oral hygiene, frequency of dental visits, medical conditions and medications being taken, root exposure, salivary flow, mutans streptococci levels, family’s dental experience, orthodontics, removable appliances, and diet. The type and nature of modifiers applicable to an individual may indicate that he/she should be moved into a different risk category. No attempt was made to regulate the number of modifiers which would move a person into a different risk category; this decision has been left up to the clinician’s judgment. However, patients should be reassessed and reclassified at subsequent recall visits for the appropriate risk category. A patient initially classified as “high-risk” or “moderate-risk” may fall into a “low-risk” category at recall if no new lesions are found and modifying factors such as fluoride exposure and oral hygiene have changed. “Low-risk” patients may also move into other categories if oral conditions change. Risk categories and classification are fluid. The following risk categories are defined and provide guidelines for preventive regimens as well as recall intervals for assessing caries risk status: Modifiers Risk Categories Low-Risk Patients A patient is considered to be at low risk if he/she has no active cavitated lesions at the examination appointment and few risk modifiers are present. For the patient at low risk, the preventive regimen includes reinforcing his/her use of fluoridated toothpaste, a review of oral hygiene procedures, and discussion of the patient’s diet. If there are incipient lesions or deep pits and fissures and/or the patient has a previous history of caries, apply sealants on all appropriate teeth. The application of sealants has been proven to be one of the best caries preventive regimens available (35-38). Low-risk patients can be advised to return to the dental clinic in 24-36 months. This time should be shortened if a patient is in a mixed dentition stage or other modifiers are present. Preventive Regimen Moderate-Risk Patients Patients with one active cavitated smooth-surface lesion at the time of the exam are considered to be at moderate risk. Again modifiers could place a patient in a higher or lower risk category. Moderate-risk patients should receive appropriate education including diet, use of fluoride, and oral hygiene at the exam appointment. Sealants should be applied to all appropriate teeth before any restorative services are provided. Based on local resources, over-the-counter daily fluoride mouthrinses or a semi-annual professionallyapplied topical fluoride treatment (foam, gel, or varnish) may be recommended or provided as appropriate (39-42). A six-month to 24-month recall should be implemented for these moderate-risk patients, depending on the number of modifiers present. For example, a patient with only one smooth-surface lesion, but deep pits and fissures, mixed dentition, poor oral hygiene, and lack of any fluoride exposure, should be recalled at shorter intervals. High-Risk Patients Patients with two to five active cavitated smooth surface lesions on permanent teeth at the time of the exam are considered to be at high risk in this protocol. Patients who were former “very high-risk patients” could also be placed in this group. Again modifiers could place a patient in a different risk category, either lower or higher. These high-risk patients should receive appropriate treatment which includes pit and fissure sealants and the restoration of carious lesions. Additional preventive treatment measures at the exam and subsequent appointments could include: professionally-applied topical fluoride treatments (foam, gel, and varnish), antimicrobial rinses, and patient education (diet, use of fluoride toothpaste, and oral hygiene). A six-month to 12-month recall should be implemented for high-risk patients, depending on the number of modifiers present. For example, a patient with two smooth-surface lesions, deep pits and fissures, good oral hygiene, and regular fluoride exposure should be recalled at the longer interval. Very High-Risk Patients Patients with six or more active cavitated smooth surface lesions on permanent teeth at the time of the exam are considered to be at very high risk. Immediate action should be taken on these very high-risk patients to reduce or eliminate their dental infection before providing definitive restorative care in the permanent dentition. At the examination appointment oral hygiene instructions should be given and patients should be instructed to brush their teeth at least twice a day with an antimicrobial product such as a chlorhexidine mouthrinse. Cavitated lesions should be eliminated as soon as possible: two or fewer appointments are recommended; definitive Preventive Regimen and Treatment restorations need not be placed at this time. Sealants should be placed on all pits and fissures as appropriate and fluoride varnish placed on decalcified areas of the teeth. An antimicrobial rinse should also be prescribed or dispensed to these patients after the cavitated lesions have been treated IHS Caries Risk Assessment Summary Risk Category Criteria No Active Cavitated Lesions Low Moderate One Active Cavitated Smooth Surface lesion High Two to Five Active Cavitated Smooth Surface Lesions Very High Six or more Active Cavitated Smooth Surface Lesions Preventive Services Review OHI Sealants if needed 24-36 Month Recall OHI Sealants as needed Fluoride (OTC and/or professional) 6-24 month Recall OHI Sealants as needed Fluoride (OTC and/or professional) 6-12 month recall OHI Antimicrobials Sealants Fluoride varnish Modifying factors: Tooth morphology, age, fluoride exposure (both too much and not enough), oral hygiene, frequency of dental visits, medical conditions and medications being taken, root exposure, salivary flow, mutans streptococci levels, family’s dental experience, orthodontics, removable appliances, and diet. References 35. Lussi A. Validity of diagnostic and treatment decisions of fissure caries. Caries Res 1991;25:296303. 36. Lussi A. Comparison of different methods for the diagnosis of fissure caries without cavitation. Caries Res 1993;27:409-416. 37. Pitts NB. The diagnosis of dental caries: lingual and occlusal surfaces. Dent Update 1991;18:393396. 38. Kidd EAM, Ricketts DNJ, Pitts NB. Occlusal caries diagnosis: a changing challenge for clinicians and epidemiologists. J Dent 1993;21:323-331. 39. Verdonschot EH, Bronkhorst EM, Burgersdijk RCW, Köng Schaeken MJM, Truin GJ. Performance of some diagnostic systems in examinations for small occlusal caries lesions. Caries Res 1992;26:59-64. 40. Longbottom C, Pitts NB. An initial comparison between endoscopic and conventional methods of caries diagnosis. Quintessence International 1990;21:531-540. 41. Bder JD, Brown JP. Dilemmas in caries diagnosis. J Am Dent Assoc 1993;124:48-50. 42. Burt BA. Cost-effectiveness of sealants in private practice and standards for use in prepaid dental care. J Am Dent Assoc 1985;110:103-107. 43. American Dental Association. Pit and fissure sealant (Report). J Am Dent Assoc 1987;114:671672. 44. Ripa LW. The current status of pit and fissure sealants: a review. Can Dent Assoc J 1985;5:367380. 45. Newbrun E. Preventing dental caries: current and prospective strategies. J Am Dent Assoc 1992;123:68-73. 46. Maxwell H, Bales DJ, Omnell K. Modern management of dental caries: the cutting edge is not the dental bur. J Am Dent Assoc 1993;124:37-44. 47. Dawson AS, Makinson OF. Dental treatment and dental health. Part 1. A review of studies in support of a philosophy of minimum intervention dentistry. Aust Dent J 1992;371:26-32. 48. Dawson AS, Makinson OF. Dental treatment and dental health. Part 2. An alternative philosophy and some new treatment modalities in operative dentistry. Aust Dent J 1992;37:205210.