What is the Magna Carta written on?

advertisement

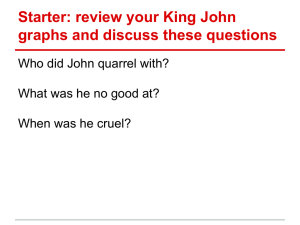

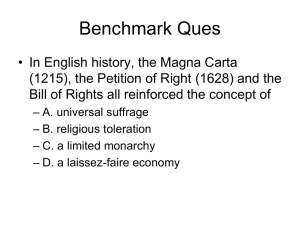

The Magna Carta CLASSROOM COPIES!!! http://www.bl.uk/treasures/magnacarta/timeline/timeline.html The Magna Carta was written because of a greedy ruler, King John. This unfair ruler disliked the rich landowners of England. To punish them, he continually raised taxes. When the people could not afford the extreme taxes, King John took their land away. Since King John controlled the courts, the people could not hope to regain their property. Then, the situation worsened when England went to war with France. King John lost much of the land held by the English in France. This enraged the landowners who owned the land King John lost. It also angered the common people of England who depended on the landowners for jobs. In order to save what was left of his kingdom, King John agreed to live by the sixtythree articles in the Magna Carta. It forced the king to seek the permission of the landowners before raising taxes. It also gave the Church freedom from the king's rule. As a result of the Magna Carta, a king or queen in England can act only with the consent of Parliament. Introduction Magna Carta is one of the most celebrated documents in English history but later interpretations have tended to obscure its real significance in 1215. This iconic document was not intended to be a lasting declaration of legal principle. It was a practical solution to a political crisis which primarily served the interests of the highest ranks of feudal society by reasserting the power of custom to limit despotic behavior by the king. The majority of the clauses in Magna Carta dealt with the regulation of feudal customs and the operation of the justice system, not with legal theory and rights. It was King John's extortionate exploitation of his feudal rights and his ruthless administration of justice that were at the core of the barons' grievances. All but three of Magna Carta's clauses have now become obsolete and been repealed, but the flexible way in which the charter has been reinterpreted through the centuries has guaranteed its status and longevity. Legacy Only three of the original clauses in Magna Carta are still law. One defends the freedom and rights of the English church, another confirms the liberties and customs of London and other towns, but the third is the most famous: No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled . nor will we proceed with force against him . except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land. To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice. This statement of principle, buried deep in Magna Carta, was given no particular prominence in 1215, but its intrinsic adaptability has allowed succeeding generations to reinterpret it for their own purposes and this has ensured its longevity. In the fourteenth century Parliament saw it as guaranteeing trial by jury. Sir Edward Coke interpreted it as a declaration of individual liberty in his conflict with the early Stuart kings and it has resonant echoes in the American Bill of Rights and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. But the real legacy of Magna Carta as a whole is that it limited the king's authority by establishing the crucial principle that the law was a power in its own right to which the king was subject. Why is the Magna Carta hard to read? The scribes who produced Magna Carta wrote in medieval Latin using the typical handwriting found in English documents in the early 13th century. The scribes also followed the usual practice of abbreviating words to save space on the parchment, because it was so expensive to produce. If you go over to the interactive in the opposite corner of the room you can use its magic magnifier to look at the Latin text in detail as well as an English translation. What is the Magna Carta written on? Magna Carta was written on parchment, not on paper. Parchment was the normal writing material in England until the end of the Middle Ages. It was made from sheepskin which was soaked in a bath of lime, then stretched on a frame to dry under tension. When it was dry, the skin was scraped with a curved knife to produce a smooth writing surface for the scribes, who wrote their text with a quill pen. Where did King John sign the Magna Carta? Like other medieval royal charters, Magna Carta was authenticated with the Great Seal, not by the signature of the King. In fact there is no evidence that King John could write at all. Three of the four surviving copies of Magna Carta have lost their wax seals over the centuries. The only one which still has its seal is the burnt copy on display here. Unfortunately the seal was destroyed when the charter was burnt by fire in 1731, but the Great Seal on display with the Articles of the Barons shows what the seal on Magna Carta would originally have looked like. Why is there more than one Magna Carta? There is no evidence that a single Magna Carta was written up and sealed when King John met the barons at Runnymede in 1215. Instead, once the terms of Magna Carta had been finalised, the barons renewed their oaths of allegiance to the king. In the days that followed, the terms of the agreement were retrospectively written up into a grant by scribes working in the royal chancery. Many copies of this grant, which later became known as Magna Carta, were sent out to bishops, sheriffs and other officials throughout the country. We don’t know exactly how many were issued, but four now survive, one in Lincoln, one in Salisbury and two here in the British Library. Why is one copy of the Magna Carta burnt? Both copies of Magna Carta in the British Library came from the enormous collection of manuscripts amassed by Sir Robert Cotton who died in 1631. Exactly a century later, in 1731, there was a disastrous fire at Ashburnam House in Westminster where his library was then housed. Many rare and valuable manuscripts were destroyed or damaged in the fire, and unfortunately one of Cotton’s two copies of Magna Carta was caught up in the blaze. What does 'Magna Carta' mean? 'Magna Carta' means 'The Great Charter'. In 1215 it was known as the Charter of Liberties, but when it was confirmed in 1217, the clauses dealing with the law of the royal forest were taken out and put into a separate document known as 'The Charter of the Forest'. After that, people began to refer to the Charter of Liberties as Magna Carta to distinguish it from the shorter Charter of the Forest. What does the Magna Carta say? Despite what many people expect, Magna Carta includes very few statements of legal principle. In fact, the majority of the 63 clauses in the charter deal with the detail of feudal rights and customs, and the administration of justice. It was King John’s excessive and arbitrary exploitation of his feudal rights, and his abuse of the justice system, which more than anything else had fuelled the barons’ rebellion in the first place. So it isn’t really surprising that the regulation of feudal rights and the justice system dominate the content of Magna Carta. How much of the Magna Carta is valid today? Only three of the 63 clauses in Magna Carta are still valid today. These are the first clause guaranteeing the liberties of the English Church; the clause confirming the privileges of the city of London and other towns; and the most famous clause of all which states that no free man shall be imprisoned, dispossessed, outlawed or exiled without the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land. The other 60 clauses were either left out of the early confirmations of Magna Carta or have become redundant and been repealed in modern times. Why is the Magna Carta important? Magna Carta was the first grant by an English king to set detailed limits on royal authority. Through its statement of liberties, it sought to prevent the king from exploiting his power in arbitrary ways and it made clear that the king was subject to the law, not above it. The Church For much of his reign, King John was in dispute with Pope Innocent III over the struggle to elect a new archbishop of Canterbury. When King John refused to recognise the papal nominee, Stephen Langton, the dispute intensified. In 1208 the pope placed an interdict on England prohibiting priests from celebrating mass, conducting marriages in church and burying the dead in consecrated ground. John retaliated by seizing the lands and income of the church, but in 1209 the pope excommunicated him, turning him into a spiritual outcast overnight. By 1212, facing the threat of a French invasion, John was forced to make peace with the church. He accepted Langton as archbishop in 1213, compensated the church for the revenues he had plundered and made the pope feudal overlord of England. This capitulation after years of bitter struggle proved to be a shrewd political act that paid off for King John after he was coerced into granting Magna Carta. Within weeks, John sent envoys to Innocent III and, before most of the charter's terms could be properly implemented, the pope declared Magna Carta null and void on 24 August 1215. Debt and money-lending Medieval Christians were forbidden from lending money at interest, whereas Jews were free to make such loans. The king and the barons depended on Jewish money-lenders because they needed financial credit, but the king also plundered Jewish wealth through punitive levies and the confiscation of property. Since the Crown had the right to collect debts owed to Jews who had died, Jewish loans to the barons were often profitable for the king and financially painful for the barons. However, Magna Carta did not ban the reversion to the Crown of debts owed to Jews. It also implicitly allowed the seizure of property for the payment of debts, it did not prohibit imprisonment for debt and the the clause dealing with intestacy specifically preserved the rights of debtors. Instead Magna Carta merely set out principles for how debts should be collected and corrected two minor abuses. If the heir of a debt to a Jew was a minor, the debt could not accrue interest, and widows and minors were to be protected from excessive demands for repayment. Feudal rights and obligations The feudal system was the framework governing all land-holding in medieval England. In the feudal hierarchy, all land was ultimately held from the king, in a complex web of tenancies stretching down from the king's tenants-in-chief, through a series of under-tenants, to the rural peasantry at the foot of the pyramid. Everyone in the hierarchy had rights and obligations regulated by long-established custom. The king was entitled to many customary payments from his tenants-in-chief. He could demand money on the marriage of his eldest daughter or when his tenants' heirs inherited their estates; he had the lucrative right of wardship over tenants' heirs who were minors and he could control the marriage of his tenants' widows and heirs. The barons also owed the king a payment called scutage in place of military service. King John repeatedly breached the bounds of customary practice by exploiting his feudal rights to excess. Over a third of the 63 clauses in Magna Carta dealt directly with these rights, defining and limiting the extent of the king's authority. Justice King John's father, Henry II, introduced extensive judicial reforms, established the authority of the royal courts and laid firm foundations for the future system of justice in England. In contrast, King John regularly abused the justice system to suppress his opponents and to extort revenue from the barons. The justice system and the feudal system were the two main themes in Magna Carta, but the most famous clause dealt with justice: No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land. The barons ensured that numerous other clauses in Magna Carta defined in more detail how the justice system and its officials were to operate. These clauses sought to remedy specific abuses by the king and to make the system more consistent, accessible and fair. Making peace Many of the clauses towards the end of Magna Carta were practical arrangements for making peace. Rather than looking forward to how the king was to behave in the future, these clauses sought to put right the wrongs done by King John. The king was immediately to return all hostages, to remove all foreign knights and mercenaries from England, to remit all fines exacted unjustly, and to restore lands, castles and liberties to all who had been wrongfully deprived of them. These clauses were not statements of legal principle, but they were a vital part of the peace-making process. Perhaps the most radical clause in Magna Carta was the 61st, which set up an elected commission of 25 barons to monitor the king's compliance with the settlement and to enforce its terms. The 25 barons had the power to seize the king's property in order to seek redress if he failed to stick to the terms imposed on him. This clause showed the innovative power of Magna Carta to limit royal autonomy. Royal forest During the 12th century, King John's predecessors declared vast and ever increasing areas of the country to be royal forest, set aside for the king's hunt. Prior to 1215 the extent of the forest was controlled by the king and John increased its limits even further. The royal forest was governed by a separate set of especially severe laws, enforced by special justices, sheriffs and wardens. All hunting was prohibited, as were bows and arrows, greyhounds, hawks and falcons, the cultivation of land and the felling of trees. Those living in the forest were unable to exploit the land's resources and were subject to fines for any breach of forest law. The barons used Magna Carta to regulate the boundaries of the forest, investigate its officials and reform forest law. This was a profound attack on a significant area of royal power which was taken even further with the issuing of the comprehensive Charter of the Forest in 1217. Towns and trade England's cities and towns were evolving rapidly in the 12th and 13th centuries. Urban populations were growing, commercial life was expanding, and the complex structures of urban administration were beginning to emerge. In London, the only large city in England, networks of craftsmen, tradesmen and shopkeepers supported a thriving urban culture and the River Thames was busy with merchant traffic. The city jealously guarded the extent of its self-governance and its financial freedoms. Only three clauses in Magna Carta are still valid today, one of which declares that London and all other cities, boroughs, towns and ports shall enjoy their ancient liberties and customs. In 1215 a number of other clauses in the charter protected the interests of traders. Fish-weirs were to be removed from rivers because they impeded navigation and trade, particularly on the Thames and Medway. National standard measures for wine, ale, corn and cloth were introduced and foreign merchants were guaranteed the right to enter and leave the country and to enjoy freedom of movement within it, in accordance with ancient customs.