Corey Howard`s Research Notes on Woolley Wives

advertisement

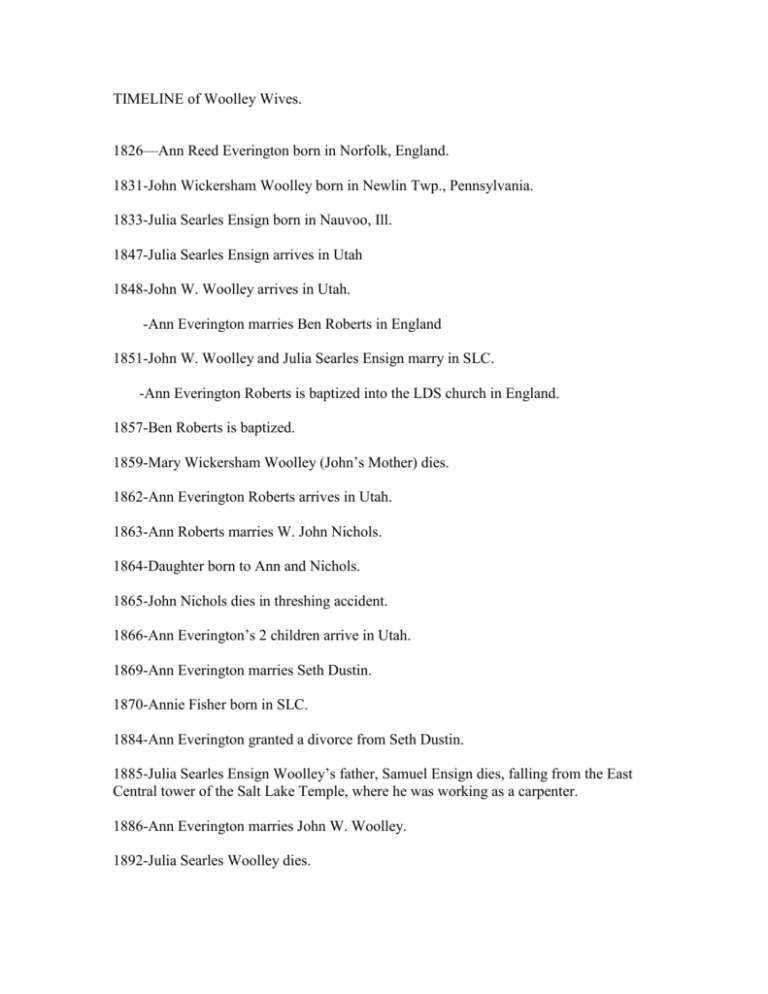

TIMELINE of Woolley Wives. 1826—Ann Reed Everington born in Norfolk, England. 1831-John Wickersham Woolley born in Newlin Twp., Pennsylvania. 1833-Julia Searles Ensign born in Nauvoo, Ill. 1847-Julia Searles Ensign arrives in Utah 1848-John W. Woolley arrives in Utah. -Ann Everington marries Ben Roberts in England 1851-John W. Woolley and Julia Searles Ensign marry in SLC. -Ann Everington Roberts is baptized into the LDS church in England. 1857-Ben Roberts is baptized. 1859-Mary Wickersham Woolley (John’s Mother) dies. 1862-Ann Everington Roberts arrives in Utah. 1863-Ann Roberts marries W. John Nichols. 1864-Daughter born to Ann and Nichols. 1865-John Nichols dies in threshing accident. 1866-Ann Everington’s 2 children arrive in Utah. 1869-Ann Everington marries Seth Dustin. 1870-Annie Fisher born in SLC. 1884-Ann Everington granted a divorce from Seth Dustin. 1885-Julia Searles Ensign Woolley’s father, Samuel Ensign dies, falling from the East Central tower of the Salt Lake Temple, where he was working as a carpenter. 1886-Ann Everington marries John W. Woolley. 1892-Julia Searles Woolley dies. 1910-Ann Woolley dies, and is buried in Bountiful. -John W. Woolley marries Annie Fisher. 1914-John W. Woolley excommunicated for continuing to seal men to plural wives. 1928-John W. Woolley dies. 1939-Annie Fisher Woolley dies. ------1) Julia Searles Ensign Woolley was a small woman, described as having “Sweet, serene patience”. She was said to be “cheerful, with a hearty laugh”. John Woolley’s father, Edwin Woolley, had been the missionary who converted the Massachusetts Ensigns to Mormonism, and the Ensign and Woolley families became even more closely associated when the Ensigns moved to Nauvoo. John was romancing Julia while they all lived in Nauvoo, per Rachel Woolley, one of John W.’s sisters who watched as a chaperone. Julia would have been 12 or 13, and John 14 or 15. Julia is a niece of Edwin Woolley’s 2nd wife, Louisa, who refused to come to Utah and continue living in polygamy. Julia and John would arrive in Utah, separately, Julia ahead of John. A guest at their Salt Lake City wedding said it “was all done up in style”, with a supper and a Ball lasting ‘til 12 midnight. Julia was 17, and John 19. When John was ordained an elder, they had their endowments taken out later in the same year. She loved animals and always had cats, dogs, and horses. Early in her marriage, she had a horse of her own-Brownie, and loved to ride. During the Underground days, Julia’s Centerville home (7 or 8 rooms) was the hiding place of many people-including President John Taylor, other apostles, bodyguards, etc. Secret plural wives with their babies were sheltered in Julia’s care, with as many as three expectant mothers at a time living there. When hanging laundry on the line, Julia would cover the baby clothes by hanging sheets over the top. This home that John Woolley bought from Charles C. Rich, had an underground storage room under the kitchen. The only access was through a trap door. The kitchen stove and rug would be moved to obscure the trap door when people were hiding below. Another secret space was under the barn. When anyone unfamiliar approached the property, their little dog would bark, and whoever was exiled there-President John Taylor, apostles, children, or secret plural wives; would duck into the closest hiding spot for the duration of the danger. People seeking shelter would arrive at the home at all hours of the night and day. Julia was known for her good cooking, especially her “Johnny cakes, cornbread, and doughnuts”. Julia took in children of her sister, and at least one young man who had arrived in Utah alone at the age of 14. Julia is regarded in the Woolley Family narrative as one who faithfully did her part, ministering to the needs of many in a “quiet and peaceful way”---supporting her husband and leaders during times of trial and persecution. 2) Ann Reed Everington Roberts Nichols Dustin Woolley Family narrative states both of Ann’s parents died early. Both parents show as living in 1841 England Census, Ann is 15. To support herself, Ann became a skilled seamstress and milliner. Ann was thoughtful, serious, and studious woman-reading whatever books she could obtain. When she fell in love with her first husband, it was his sunny, genial nature that drew her to him. She told her daughters she had been “quite swept away” by him. To supplement her husband’s erratic income, Ann took in sewing, as she had before her marriage. It was on one of her walks to deliver finished goods, that she encountered the missionaries. It wasn’t long before Ann was converted, but not her husband. She went in secret to be baptized, and tried to dry her clothes to prevent Ben from discovering this. He noticed the damp, however, and said “Ann, I believe thee’s been dipped!” Ben would eventually be baptized, and faithfully paid tithing. Family lore holds that Ann had tried to convince Ben to emigrate, but he was not interested. He had been chastised by local church leaders, excommunicated and shunned by local members. He wanted nothing to do with Mormonism after that. When Son B.H. Roberts is born, Ben named him Henry, but Ann secretly had the missionaries bless him as “Brigham Henry”, after Brigham Young. Ben’s work took him away from home, and he would send money—sometimes little and sometimes more. One particular time, he sent quite a bit, instructing Ann to bring the children and come live where he was working. Ann, having been wishing to emigrate to America and Zion, instead went to ask advice from the church leadership. She came away from that meeting with the decision to use the money to take herself and 2 of her 4 living children to America. Two children (5 and 11 years old) were left behind in England to be retrieved later. Ben would not know what happened until he received her letter, and Ann was already enroute to the United States. Four years later, after much hardship, the two children in England would make it to Utah. Still loving Ann, he was outraged and betrayed that she left without him. Ann’s family narrative holds that though she married three times after Ben, none of those marriages produced the love she had known with him in England. One version said that she had hoped that by her leaving alone, he would be motivated to follow her to America. Crossing the plains, Ann would lose her youngest child, a son who had been ill his entire, short life. In Utah, she married a man who had befriended her on the journey-John Nichols. They had a daughter within a year of marrying, but John was killed in a threshing accident when the girl was only a year and a half old. All of this took place before the return of her two children from England. When Mary and younger brother Harry (B.H. Roberts) arrived, they saw her home-made of logs, with a dirt roof over most of the structure, but a piece had been added with unchinked log walls, and no roof. Three years later, Ann would marry again. This time to Seth Dustin, a widower with young children to raise. This was a rough marriage, and once his children from his first marriage reached independence, Seth’s absences increased in frequency. In 1884, Ann and Seth divorced. One daughter was born of their relationship. In 1886, Ann would become John W. Woolley’s only plural wife. Their arrangement was said to be a marriage of convenience and fortune. This was probably a relief for Ann. There is no record of them sharing a home. When Julia Woolley died in 1892, John W. married Ann legally in the eyes of the state. The 1900 census shows John maintaining a his Centerville home with a daughter (Elizabeth), a widowed sister-wife (Ruth Kelson Ensign) of Julia Searles’ mother (Mary Gordon Ensign), and two of Ruth’s grandchildren (Horace and Samuel Ensign [Rugg]), their mother (Mary Ann Ensign)having died, and father (Harry Beaumont Rugg) apparently on the underground due to cohab prosecutions. By 1910, these extra family members are living with another of Ruth’s sons. Ruth dies in 1916. Ann, meanwhile is living in Bountiful, with a granddaughter, and another of Ruth Ensign’s grandchildren (also a child of Harry Rugg). Ann died in 1910, and was buried by John Woolley with his last name on the headstone. Son B.H. Roberts vowed to have her headstone replaced to remove “Woolley” and return her name of record to “Roberts”. This he accomplished. I am not certain why B. H. Roberts held such a strong dislike for the Woolley name. There is nothing I can find written about Ann and John W.’s relationship-other than it was financially suitable for them both. In his youth, BHR had been disfellowshipped briefly by John W.’s father, Edwin, but BHR always retold that story as if it had been a positive turning point in his life. Possibly, the story of BHR and Ann’s headstone comes from after John W.’s excommunication, and BHR did not want his mother’s memory connected to an apostate. She was survived by 5 of her 9 children. She was very active in Bountiful Primary and school programs for 30 years. She helped raise many other children, not her own, including her grandchildren and children from Julia Searles’ family. 3) Annie Fisher Woolley was John’s third wife. Annie’s parents, Edward and Margaret Potts Fisher, were from England, and came to Salt Lake in 1866 as a couple. Annie appears to have been an only child-the only one to appear on the census, at least. Per the census, Annie’s father had been a shoemaker during her childhood, but is listed as a day laborer on the census and his death certificate. The Daughters of the Utah Pioneers lesson material on John W. Woolley states that Annie and her mother Margaret had entered the Woolley household originally as housekeepers. A life sketch of John W. Woolley, submitted by one of his descendants, states that John first met Annie Fisher while he was working in the Salt Lake Temple. The story told says John asked Annie and her mother to come live in his Centerville home. This one narrative phrases the situation as if the invitation took place while Ann Everington was yet living, but makes it clear that John did not actually marry Annie Fisher until 1910--after Ann Everington’s death. There are enough errors or instances of “glossing over’ in this particular history, that it is impossible to ascertain whether Annie lived with John as a plural wife, or not. There would not likely be a record of a plural marriage in any case, as Annie and John met post-Manifesto. The family says that she was very devoted, and took excellent care of him through his “old age and last illness.” The grandchildren called her “Grandpa’s Annie”. From descendant –submitted histories, which make no mention of JWW’s excommunication for performing plural marriages post-Manifesto in 1914, the story is given as follows: In keeping with the family reputation, John Woolley continued to work in the Davis Stake High Council until the age of 82, when he retired because of hearing loss. He was described as headstrong and set in his ways. The addition of hearing loss made it very difficult to take part in public affairs. He still walked a few miles daily, chopped wood, and worked at many of the odd jobs necessary to maintain his property. This separation from the High Council is said to have occurred in 1913. Both Annie and her mother, Margaret, are listed in John W. Woolley’s household in 1910 and 1920 censuses. Margaret died in 1926. John Woolley died of a stroke in 1928. Annie Fisher Woolley lived until 1939. Since Annie was not known to have been married prior to John Woolley, nor did she have any children, there is heartbreakingly little record of her life to be found in a semithorough search. It may be that more information is recorded about her in ward records, or perhaps temple books from that time, but no descendants means no one wrote her story, no one knows if she made good pies, if she could sing beautifully, or what memories she held dear from her childhood. Likewise, with her invisibility comes the invisibility of her parents, and their pioneer story. Also of interest—anecdotes regarding John Woolley’s Mother Mary: In 1843, the revelation regarding Celestial Marriage was first read in Edwin C. and Mary Wickersham Woolley’s home. Both Hyrum and Joseph Smith taught the newly revealed principles personally in the Woolley home. One daughter, Rachel, wrote of slipping downstairs when she ought to have been sleeping, and eavesdropping on instruction, or observing early ceremonies. Mary, the matriarch, told John herself about Edwin’s secret marriages to Louise Gordon and Ellen Wilding, under strict orders not to divulge any of it. Although Mary had consented to plural marriage-the revelation having been first publicly read in her home, Mary “had difficulty” in accepting the relationship. In April of 1844, she took her baby Henrietta and returned to her parents’ home in Ohio. She sent a letter from Ohio to Nauvoo, part of which reads: “I am all alone with many strangers. Oh Edwin, the tears fall so fast from my eyes that I cannot see to write. When I look back west my soul would exclaim O my husband, my children, where are you? I have just been pouring out my soul to my God for consolation in my afflictions for I have no husband to comfort me. My heart is with thee, and thee alone, for thee I live, and for thee I die. I want thee to be wise. What is there that I have not sacrificed?” She goes on to remind him that he [Edwin] knows her feelings and that they are still the same. Mary returned to Nauvoo and Edwin in late May or early June Mary’s daughter Rachel wrote publicly of plural marriage in a positive light, but recorded privately of Mary’s heartbreak; “There would be days together that she [Mary] would not leave the room. Often I have gone there and found her crying, as though her heart would break.” In June of 1846, when the family was driven from Nauvoo, Mary and Louisa (Aunt to John Woolley’s eventual wife Julia) were having difficulties being wives in the same household, when it was time for the Woolleys to leave, Louisa refused to go, and stayed in Ohio with her son by Edwin. Edwin, Mary Ensign Woolley, and Ellen Wilding Woolley all pleaded for her to come along, but Louisa would not. Louisa reportedly “wrote of kindly feelings in Mary’s autograph book.” Edwin would eventually return to the Northeast to retrieve his son, after Louisa died. Mary would suffer a sudden decline in health in her late forties, and spent the last two years of her life as a near-invalid under the care of a hired nurse. (This nurse would dilute Mary’s coffee, and steal the excess saved this way for herself). The cause of Mary’s death was unknown, though she lingered so long. Thomsonian herbal medicine was implemented at this time, as university doctors were feared because of the use of morphine, mercury, and lead. It was supposed that she “took cold” at a precious time (menopause). The “checked nature’s course” could not be started again, and “it appeared the blood flowed too much to her head and caused a severe pain particularly at times and fainting and unconscious at intervals somewhat similar to light attacks to which she was subject in her younger days.” Mary would die in her sleep at the age of 51. Edwin wrote to Mary’s non-LDS family: “Edwin wrote a long letter to her nonmember family in Ohio: “I do not know, but some of you may think that [as] I have other wives and children, that my first wife may have been neglected, but for your comfort in this trying hour I will say to you, she was my first wife, the wife of my youth and for whom I never lost my first love. She is as dear today to me as the day I took her from your door and never has it been otherwise.”