PVDwalk - Brown University

advertisement

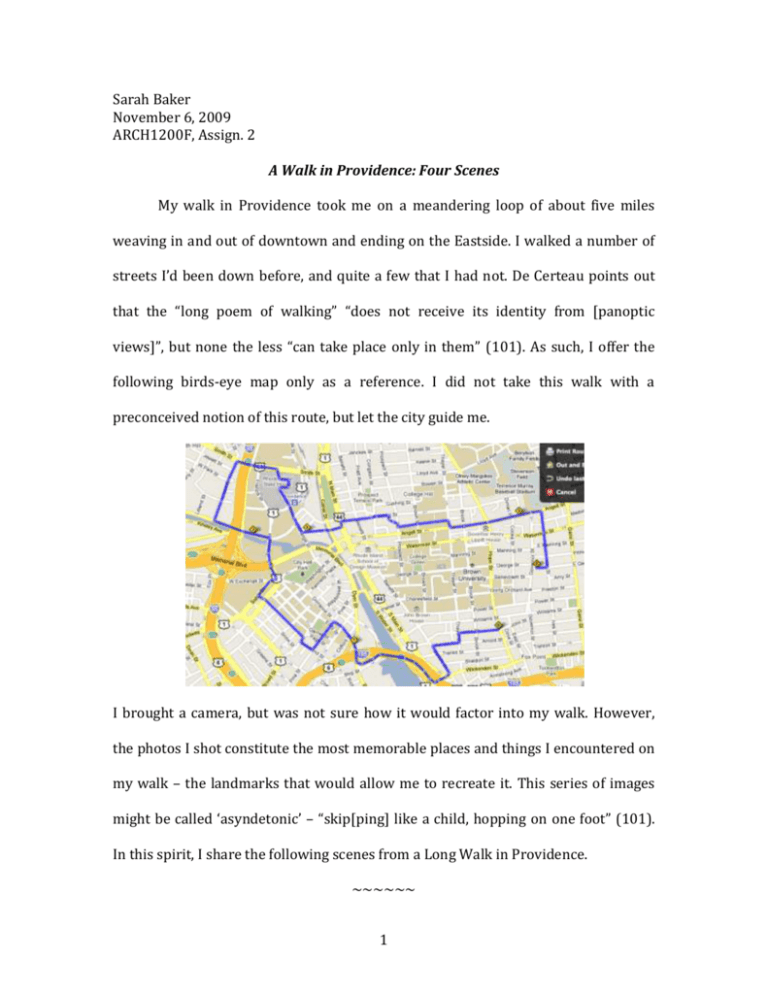

Sarah Baker November 6, 2009 ARCH1200F, Assign. 2 A Walk in Providence: Four Scenes My walk in Providence took me on a meandering loop of about five miles weaving in and out of downtown and ending on the Eastside. I walked a number of streets I’d been down before, and quite a few that I had not. De Certeau points out that the “long poem of walking” “does not receive its identity from [panoptic views]”, but none the less “can take place only in them” (101). As such, I offer the following birds-eye map only as a reference. I did not take this walk with a preconceived notion of this route, but let the city guide me. I brought a camera, but was not sure how it would factor into my walk. However, the photos I shot constitute the most memorable places and things I encountered on my walk – the landmarks that would allow me to recreate it. This series of images might be called ‘asyndetonic’ – “skip[ping] like a child, hopping on one foot” (101). In this spirit, I share the following scenes from a Long Walk in Providence. ~~~~~~ 1 I. The Abandoned Highway Walking an abandoned highway makes one wonder if a highway is still a highway if it doesn’t have cars travelling on it. The abandoned highway is eerie, perhaps because we usually encounter this space as inhabitants of automobiles. In this way, we experience only an image of the highway; our idea of ‘highway’ becomes a brief blur and a low hum as it passes by the windows of the car. We never experience it in a multi-sensory way; we do not know its materiality and its soundscape. Though I was initially drawn towards the Point Street Bridge on my walk, it occurred to me that, though the 195 bridge is closed to cars, I could easily slip through the barricade and up onto the former highway. Once I walked up the onramp, I couldn’t resist crossing the bridge, despite the uncomfortable silence and unfamiliarity of the space. I dared myself touch the concrete floor of the highway; this made me tense up, as if expecting a car to suddenly crash through the scene and through me. It made me feel small and fragile. I felt drawn away from the center, 2 compelled to walk in the safety of edge, despite being the only moving thing as far as I could see in both directions. This unfamiliar space seemed so much larger to me as a walker than as a passenger in a car. The lanes were expansively wide and its length seemed to stretch to the horizon. It seemed hardly human-scale, almost alien. This was not a space built for walkers in the first place, and, furthermore, it is a space that is now blockaded off, designated “Wrong Way”, “Road Closed”, and “Do Not Enter” by signs at every entrance. I was not supposed to walk here, partly because of its intended function, and partly because of its current state of ruin. And yet, here I was, walking down the centerline of an abandoned highway. Despite the controls and limitations placed on city spaces, my walk here shows the immense flexibility, and, hence, power, available to the walker of the city. ~~~~~~ II. Shadows in the Brick Downtown Providence is rife with echoes of past buildings, spaces, and meanings. My walk brought me past empty buildings, abandoned facades still 3 standing, architectural rubble in vacant lots, plaques denoting flood heights and names of architects; these were just a few among many shadows of the past still visible in the built environment. Perhaps the most poetic of these are the numerous brick palimpsests visible on the sides of older buildings. During my walk, I encountered the echoes of demolished buildings that used to share walls with stillstanding ones, multiple changes in windows and ventilation, the architectural integration of new additions still readable changes in brick, and other suggestions of the past urban fabric. The building pictured above looks extremely odd, standing as an island surrounded by parking lots. However, the bricks on the sides not facing the street tell the walker many stories about this building’s life before it became an island. The outlines of previously shared walls remain. Once upon a time, as shown below, there must have been a circular window in the wall of this building, too. Though these palimpsests tell us about what used to be in a space, they don’t tell us why a certain building survived to bear these urban echoes. This is left up to the imagination of the walker. 4 ~~~~~~ III: Marking The Sidewalk Though perhaps not to the same degree as a highway, we are also somewhat removed from the materiality of a sidewalk. We only touch them with our shoes, and use them without much consideration to their histories or futures. Though they can facilitate the best experiences of cities, the physical construction of a sidewalk is boring: gray, cheap, utilitarian, ubiquitous. The sidewalk as an urban experience is more of a function than a place. However, as a place, the sidewalk is liminal, occupying the murky space between public and private lives. Near the end of my walk, I found a beautiful example of how individuals had taken this nebulous and perhaps unexamined space and sought to define it – to give it a specific life and context. There were two child-sized handprints, accompanied by two names in girlish handwriting and several European coins pressed into the sidewalk. This patch of sidewalk looked newer than those around it – less encrusted with dirt and less 5 weathered. Without conscious thought, my mind constructed a story about how this patch came to look as it does today: workers were going around the city repairing squares of ruined sidewalk. At night, after their work, they would leave orange traffic cones around the fixed patches. Brenna and Anna lived near this patch, and snuck out late in the evening to inscribe their names and hands, and place a few treasured objects into the concrete outside their house. This story is purely conjecture, but inspired by a mere touch of my hand to their square of pavement. ~~~~~~ IV: City Skeletons I took my walk on Halloween, and encountered two human inscriptions in the urban fabric that made me feel as though this was quite appropriate. I happened open a homemade Halloween decoration – a colored pencil, life-sized skeleton representation – and, just a block away, the tombstone of a Puritan named “Pardon”. 6 These two images of death in the urban context were striking – almost entertaining in their ironic juxtaposition. As with the inscribed sidewalk, I immediately began to construct a narrative for the skeleton drawing. The author, undoubtedly a small boy of about six or seven, decided to use his project time in class to trace himself and draw a life-size skeleton in the outline. He carefully folded it up at the end of the day, not stuffing it in his backpack with the rest of his papers and belongings. He brought it home to his mother, who (somewhat reluctantly) entertained his insistence that the poster be hung on the outside of the house. “Just for today,” she made him promise. Pardon’s grave did not inspire the same specifics of imagination, but his grave filled me with many questions. Did he ask to be buried here, and, if so, why? Why have his grave and the surrounding open space been so well preserved, especially on densely developed Benefit Street? Has his grave served as the inspiration for ghost stories and superstitions told by older siblings to the little kids of the block? What would Pardon think of the child’s exaggerated skeleton drawing hanging a block away from his solemn obelisk? Maybe he’s rolling in his grave… 7 Works Cited De Certeau, Michel. “Walking in the City”. In The practice of everyday life, trans. S. Rendall. University of California Press: Berkeley, 1984. 8