Youth Development Program Participation and Intentional-Self

advertisement

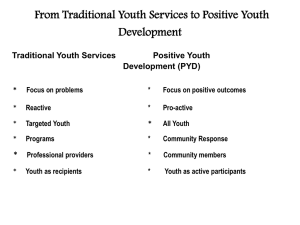

Running head: YD PARTICIPATION AND INTENTIONAL SELF-REGULATION Youth Development Program Participation and Intentional-Self Regulation Skills: Contextual and Individual Bases of Pathways to Positive Youth Development1 Megan Kiely Mueller Erin Phelps Edmond P. Bowers Jennifer P. Agans Tufts University Jennifer Brown Urban Montclair State University Richard M. Lerner Tufts University Submitted: February 28, 2011 1 This research was supported in part by grants from the National 4-H Council and the Thrive Foundation for Youth. Address correspondence to: Megan Kiely Mueller, Institute for Applied Research in Youth Development, Tufts University, 301 Lincoln Filene Building, Medford, MA 02155; e-mail: megan.kiely@tufts.edu. 1 YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 2 Abstract The present research used data from Grades 8, 9, and 10 of the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development in order to better elucidate the process through which the strengths of youth and the ecological resources promoting healthy development (such as out-of-school-time programs) may contribute to thriving. We examined the relationship between adolescents’ selfregulation skills (selection, optimization, and compensation) and their participation in youth development (YD) programs across Grades 8 and 9 in predicting Grade 10 PYD and Contribution. Results indicated that while self-regulation skills alone predicted PYD, selfregulation and YD program participation both predicted Contribution. In addition, Grade 8 YD participation positively predicted Grade 9 self-regulation, which, in turn, predicted Grade 10 PYD and Contribution. We discuss how the alignment of youth strengths and resources within the environment may promote positive youth development. YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 3 Youth Development Program Participation and Intentional-Self Regulation Skills: Contextual and Individual Bases of Pathways to Positive Youth Development Both theory and research suggest that high quality youth development (YD) programs are a strong contextual asset for promoting positive outcomes in the lives of diverse youth (Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Mahoney, Vandell, Simkins, & Zarrett, 2009). However, given the limited resources available for such programs, it is critical to explore the ways that youth can benefit maximally from such programs. Therefore, the present research aims to explore the links among individual characteristics of adolescents, their use of (or capitalization on) the resources provided by participation across time in a quality YD program, and their positive youth development. Adolescent Development and the Positive Youth Development (PYD) Perspective Traditionally, adolescence has been considered a time of “storm and stress,” with universal, biologically-based changes inevitably driving adolescents to a period of emotional and physical conflict and stress (e.g., Hall, 1904). This approach to adolescent research was based on a biological reductionism that fostered the view that adolescents were simply “problems to be managed” (Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2003) and that, practically speaking, research should focus on preventing or ameliorating the inevitable biologically (e.g., genetically) predetermined negative consequences of the adolescent period (e.g., Erikson, 1968; Freud, 1969). In turn, however, developmental systems theories provide a useful and optimistic theoretical frame for studying adolescent development in particular. Developmental systems theories indicate that youth should be studied not in isolation but, instead, as the product of the bidirectional relationship between the individual and his or her environment Much contemporary research in human development is framed by these relational, developmental systems models (Overton, 2010), which emphasize that the fundamental process YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 4 of human development involves mutually influential relations between the developing individual and the multiple levels of the ecology of human development, represented as individual context relations. This framework rejects the reductionist notion of genetically predetermined outcomes, and because of its emphasis on plasticity, affords the idea that multiple directions of change (from problematic to positive) could derive from variation in an adolescent’s history of individual context relations. Current developmental research has been shaped by the innovations brought about by the positive youth development (PYD) perspective (J. Lerner, Phelps, Forman, & Bowers, 2009). As such, researchers consider the integrated role of multiple contexts of adolescent development, such as the family, peers, and schools in providing a basis for, and outcome of, the actions of people developing across this period of life (e.g., Lerner et al., 2005, Theokas & Lerner, 2006). The PYD perspective has been derived from theory and, as well, from the work of practitioners interested in developing programs or policies to enhance youth development, as opposed to decreasing the purported deficits in their behavior (Deschenes, McDonald, & McLaughlin, 2004; J. Lerner et al., 2009). Because of this confluence of research, theory, and practice, there has been increasing attention paid to the role of community-based, youth-serving organizations, and how they may provide resources that promote positive development (Li, Bebiroglu, Phelps, & Lerner, 2009). As designed facets of the ecology, programmatic experiences intended to foster positive development among youth may be a potentially powerful basis of support of PYD. Youth Development Programs and PYD An extensive body of research has shown that high quality, structured out-of-school-time (OST) programs promote a host of positive outcomes including, but not limited to, initiative skills (Larson, 2000), academic achievement (Zaff, Moore, Papillo, & Williams, 2003), civic YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 5 engagement (Sherrod & Lauckhardt, 2009; Stoneman, 2002), and overall positive youth development (J. Lerner et al., 2009). Furthermore, adolescence is an important period for identity development and for structuring positive and prosocial peer relations, and activity participation is a context in which this development may be fostered (Barber, Stone, Hunt, & Eccles, 2005; Mahoney et al., 2009). It is clear from the extant research that participation in structured OST activities is a developmental asset vital to promoting PYD (Lerner, 2005; Zarrett et al., 2009). As the nature and quality of youth OST activity involvement is critical to positive development, it is important to delineate the precise features of programs that serve as crucial developmental assets for youth. Youth development (YD) programs are a subset of OST programs that include structured activities that are deliberately intended to affect positive developmental outcomes (Lerner, 2004). Such programs often contain the “Big Three” (Lerner, 2004) program characteristics shown to promote positive development, that is: 1. positive and sustained (for at least one year; Rhodes, 2002) adult-youth relations, such as mentoring; 2. youth life-skill building activities; and 3. youth participation in and leadership of valued community activities (Zaff, Hart, Flanagan, Youniss, & Levine, 2010). YD programs, such as 4-H Clubs and other after school programs that incorporate the “Big Three” characteristics, provide a structured environment that serves as a developmental asset encouraging youth to take leadership and agency in their development (Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Larson, 2000) and to develop needed and useful life skills (Mahoney, Larson, Eccles, & Lord, 2005). Greater participation in such programs has been linked to indicators of PYD (Balsano, Phelps, Theokas, Lerner, & Lerner, 2009; Mahoney et al., 2009), and to the growth of positive outcomes such as higher grades, school value, self-esteem, and resilient functioning (Fredricks & Eccles, 2005). YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 6 However, it is important to note that while research suggests that increased participation in OST activities is linked to positive developmental outcomes (e.g., Mahoney et al., 2009), research by Zarrett and colleagues (2009) suggests that a more nuanced relationship exists. Zarrett et al. found that, in some instances, higher activity participation can lead to higher PYD, but also to higher risk of depression. In addition, patterns of participation may affect developmental outcomes differentially. Zarrett and colleagues found that for middle school youth, the benefits of participating in sports differed depending on the other types of activities in which youth also participated (Zarrett, Peltz, Fay, Li, & Lerner, 2007). This research points to the complexity in which youth participation in OST activities can have an impact on development, and suggests that a more nuanced approach is necessary, one that establishes how much and what kind of programs are beneficial to youth of particular characteristics. Intentional Self-Regulation as an Individual Strength Research on the strengths that youth bring to their interactions with their contexts has increasingly assessed adolescents’ abilities to seek out and acquire the resources possessed by these organizations to promote their development (Mueller, Lewin-Bizan, & Urban, in press). Are there particular characteristics of youth that may be linked to effectively engaging in YD programs in ways that maximize the probability of PYD? Gestsdóttir and colleagues (Gestsdóttir & Lerner, 2007, 2008; Gestsdóttir, Lewin-Bizan, von Eye, Lerner, & Lerner, 2009) have suggested that intentional self-regulation behaviors, involving the selection of positive or developmentally beneficial goals, acting to optimize the resources needed to make such goals a reality, and possessing the ability to compensate effectively when goals are blocked, are the characteristics that youth need to seek out and maximally use the resources in the environment, such as those represented by (or found within) YD programs. These selection (S), optimization YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 7 (O), and compensation (C) skills (i.e., SOC skills) provide a set of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral attributes that an individual employs to contribute to mutually beneficial relations with his or her context (Freund & Baltes, 2002; Gestsdóttir & Lerner, 2008; Lerner, Freund, De Stefanis, & Habernas, 2001). The SOC model offers a framework for understanding adolescents’ abilities to influence or select from and use the resources in the context of the YD program that is, in turn, influencing them. Prior research has indicated that SOC skills are predictive of PYD outcomes (e.g., Gestsdóttir & Lerner, 2007; Zimmerman, Phelps, & Lerner, 2007), with high SOC scores associated with the highest PYD trajectories (Zimmerman, Phelps, & Lerner, 2008). Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that SOC scores, as an index of the presence of the individual’s potential contribution to mutually beneficial relations with his or her context, when coupled with participation in YD programs, constitutes a relational structure linked to PYD. That is, if YD programs are structured to provide youth with the developmental assets of positive adult relationships, skill building, and leadership opportunities, then, alignment with individual strengths, such as intentional self-regulation, should constitute an ideal relation for promoting the positive individual context relationships that result in PYD. The Present Research: YD Program Participation, SOC Skills, PYD, and Contribution The purpose of the present research, therefore, is to better understand how adolescents’ SOC skills are linked to the assets of YD programs. As well, the purpose is to ascertain the sequence of the development of SOC skills and participation in YD programs. That is, do individuals with high SOC skills self-select into YD programs (presumably in order to obtain the resources that they need to achieve their goals)? Or, alternatively, do YD programs provide YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 8 youth with the resources that are linked to subsequent development of intentional self-regulation skills? The fact that YD programs are linked in the extant literature to SOC skills (Lerner, 2004) suggests that greater “dosages” of YD program involvement should co-vary with higher SOC scores. Past research indicates that high quality, structured YD programs containing the “Big Three” (e.g., 4-H Clubs) serve as a source of contextual assets for youth (Theokas & Lerner, 2006). Therefore, under the assumption that high quality YD programs provide resources to youth and that intentional self-regulation skills may afford a means by which youth access the assets of programs, the present research expands upon past findings by directly testing the link between YD program involvement, SOC scores, PYD, and Contribution (an important outcome related to youth contributing to their community, family etc., and one that YD programs such as 4-H often focus on in particular; National 4-H Council, 2010). Accordingly, we will capitalize on data from the 4-H Study of PYD, a longitudinal investigation that initially studied a cohort of fifth graders and now includes information through the twelfth grade (Bowers et al., 2010; Lerner et al., 2005; Phelps et al., 2007; Phelps et al., 2009). Within the 4-H study, youth strengths are operationalized by a measure associated with the SOC model, which assesses adolescents’ adaptive intentional self-regulation skills. In addition, we will use measures of the activities that youth engage in outside of school, operationalized by both number of activities and intensity (frequency per month) of involvement; these measures will capture the benefits afforded by both diverse and frequent participation in youth development programs. Along with the individual strengths of intentional self-regulation skills and the contextual assets afforded by YD program participation, the 4-H study also provides measures of PYD YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 9 (conceptualized by the “Five Cs” – Competence, Confidence, Connection, Character, and Caring; Lerner, 2004, 2009). These concepts are used to assess domains of healthy development and characteristics that place youth on a life trajectory marked by mutually beneficial individual context relations that in turn, lead to the “Sixth C” of youth Contribution (e.g., contribution to self, family, community, society; Lerner, 2004, 2009; Lerner et al., 2005). Measures of the “Five Cs” and of Contribution are used to assess the benefits of adolescent participation in YD programs (Eccles & Gootman, 2002; Roth & Brooks-Gunn, 2003) and are recognized as indicators of a “thriving youth” (King et al., 2005). In sum, the measures used in the present study (i.e., of YD program participation, SOC, PYD, and Contribution) enable the fundamental question of this study to be addressed: How does the combination of youth strengths, as operationalized by SOC, and the contextual asset of participation in youth development programs, combine within and across time to promote to mutually beneficial relations that may lead to thriving among youth? Past research has shown consistent links between YD program participation and both PYD and Contribution (Lerner, Lerner, & Phelps, 2008, 2009). As such, the present research aims to explore the relationship between YD program participation, SOC skills, PYD, and Contribution in more detail, and to ascertain the development sequence of this relationship. Method Participants and Procedure Sample. The current study included a subset of participants in the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development, a national, longitudinal study. Overall, across the first six waves of the study, 6,120 youth (59% female) in 41 states were surveyed, along with 3,084 of their parents. YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 10 Across the first six waves, 2,527 of these students were tested two or more times. The present study utilized a subsample of youth from Grades 8 through 10 (Waves 4 through 6). In Grade 8 (Wave 4), 1,990), 2,051 youth were surveyed from 17 states along with 563 of their parents. These youth were 62.2% female, with a mean age of 14.40 years (SD = 1.41). Selfreported race for these youth was American Indian, 1.5%; Asian American, 2.6%; African American, 8.2%; Latino/a, 11.5%; European American, 73.3%; and Multiracial 2.9%. In Grade 9 (Wave 5), 1,208 youth were surveyed from 18 states along with 292 of their parents. These youth were 60.5% female, with a mean age of 14.93 years (SD = 1.10). Selfreported race for these youth was American Indian, 3.1%; Asian American, 2.8%; African American, 9.6%; Latino/a, 11.3%; European American, 67.8%; and Multiracial, 3.1 %. In Grade 10 (Wave 6), 2,488 youth were surveyed from 32 states along with 341 of their parents. These youth were 63.6% female, with a mean age of 15.71 years (SD= 1.38). Selfreported race for these youth was American Indian, 1.1%; Asian American, 1.7 %; African American, 7.2%; Latino/a, 7.2%; European American, 77.6%; and Multiracial, 2.9%. The current study uses a subsample of 895 youth from Grades 8, 9, and 10 (Waves 4, 5, and 6); the selection criterion was participation in the study at least two of the three grades. The youth in this subsample were 62.7% female and self-reported race was 1.5% Native American, 3.2% Asian or Pacific Islander, 7.5% African American, 6.9% Latino/a, 64.9% European American, and 1.0% Multiracial. In addition, 14.5% of participants reported race inconsistently across waves of participation. Based on research documenting the link between maternal education and youth’s educational and career attainment (e.g., Hauser & Featherman, 1976), maternal education was used as an indicator of participants’ socioeconomic background/status (SES). The items pertinent to maternal education asked about mother’s/guardian’s (and both if YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 11 the participating guardian is not the child’s mother) education level. There are nine categories, from 8th Grade or less to doctoral degree, with higher scores indicating higher levels (i.e., more years) of formal education. The variable was recoded to reflect the number of years of education, and ranges from 8 to 20. In the current subsample, the mean number of years of maternal education was 14.26 (SD = 2.43). Procedure. In Grades 8, 9, and 10 (Waves 4, 5, and 6 ), for youth that were surveyed in their schools or youth programs, teachers or program staff gave each child an envelope to take home to the parent or guardian. The envelope contained a letter explaining the study, two consent forms (one that was returned to the school and one that could be kept for the records of the parent or guardian), a parent questionnaire, and a self-addressed stamped envelope for returning the parent questionnaire and consent form. For the youth surveys, data collection was conducted by trained study staff or assistants hired at more distant locations. A detailed protocol was used to ensure that data collection was administered uniformly and to ensure the return of all study materials. The procedure began with reading the instructions for the student questionnaire to the youth. Participants were instructed that they could skip any questions they did not wish to answer. A two-hour block of time was allotted for data collection, which included one or two short rest periods. For youth who were absent on the day of the survey or were from schools who did not allow on-site testing were contacted by e-mail, mail, or phone, and were asked to complete the survey. Beginning in Wave 5, youth could go online to complete the survey. Youth participating in 4-H clubs were given the paper survey or used club computers to complete the survey online. Lerner et al. (2005) provides complete details about the methodology of the 4-H study. YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 12 Attrition. Attrition in the 4-H Study sample is not randomly distributed across schools or youth program sites. In Grades 4, 5, and 6, many of the schools that were originally sites for data collection did not allow us to conduct on-site surveys. Youth in these schools were contacted through mail or phone and were asked to complete the survey and mail it back to us, or to go online to complete it. Since we consistently contact all youth who ever participated in the study, many youth who were not surveyed in earlier waves of the study came back into the study in later waves. During Grades 4, 5 and 6, we continued to contact all youth who were part of the first three waves and, in addition, we increased the sample by expanding our recruitment of youth in 4-H clubs around the country. Table 1 presents the grade and variable non-response, two possible types of nonresponse, in Grades 8 through 10. Grade non-response ranged from 45.3% to 73.6%, and variable non-response at each wave ranged from 1.4% to 10.1% across the three grades. In addition, t-tests and χ2 tests were conducted to compare attrition vs. non-attrition groups (of the entire sample of youth who participated in Grades 8 to 10) on background variables (i.e., sex and mother’s education) as well as on each outcome variable (PYD and Contribution). The results indicated that participants who dropped out of the study between Grades 8 and 9 or Grades 9 and 10 did not differ significantly in their PYD or Contribution scores. However, participants who dropped out between Grades 8 and 9 had significantly lower maternal education scores than those who did not drop out. In addition, youth who dropped out between Grades 9 and 10 were more likely to be boys than youth who did not drop out. Finally, multivariate logistic regression analyses of missingness for each outcome variable (Grade 10 PYD and Contribution) indicated that the data appear to be missing completely at random; in other words, missingness among outcome variables did not appear to be related to other characteristics of the participants. YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 13 Participants’ sex, mother’s education level, and Grade 10 selection, optimization, and compensation scores were not significant predictors of missing data for PYD or Contribution. For the purpose of this research, missing data were imputed for the longitudinal subsample (N=895) with LISREL 8.80 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2006), using the Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm. ----------------------------------------Insert Table 1 about here ----------------------------------------Measures In the current study, indices of several constructs were used, in addition to several demographic variables. These measures involved assessment of youth development (YD) program participation as well as indices of several individual characteristics including intentional self-regulation and positive youth development (PYD). Maternal education was used as an indicator of socioeconomic status. YD Program Participation. Participation in YD programs was operationalized in several ways. In the 4-H study, the YD programs that participants are specifically asked about include 4H clubs, 4-H after school programs, Girl Scouts/Boy Scouts, Big Brother Big Sister, YMCA, and Boys and Girls Clubs. Intensity of participation was measured by asking youth how often they participated in each of the programs, from “never,” “once a month or less,” “a couple of times a month or more,” “once a week,” “a few times a week,” to “every day.” The variable was recoded to reflect the number of days per month (assuming a four week month, with five school days a week) youth participated in a program (0-20), and then a mean intensity score was calculated across all YD programs. In addition, we assessed how many YD programs youth participated in YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 14 (0 to 6) at each of Grades 8 and 9 (youth had to participate “at least a couple of times a month or more” in order for their participation to count). Participants who did not respond to any of the activity participation questions were considered to have missing data for YD program participation. Intentional Self-Regulation Skills (SOC). The Selection, Optimization, and Compensation (SOC) questionnaire (Freund & Baltes, 2002) was used to measure intentional self-regulation at Grades 8 and 9. Three subscales were used from the short version of the SOC Questionnaire: Elective Selection, Optimization, and Compensation. Elective Selection (S) represents the development of preferences or goals and the construction of a goal hierarchy and the commitment to a set of goals. Optimization (O) refers to acquisition and investment of goalrelevant means to achieve one’s goals. Compensation (C) refers to the use of alternative means to maintain a given level of functioning when specific goal-relevant means are not available anymore. Each of the subscales has six items with a forced-choice format. Each item consists of two statements, one describing behavior reflecting S, O, or C and the other describing a nonSOC related behavior. Participants are asked to decide which of the statements is more similar to how they would behave. An item from the Elective Selection subscale is “I concentrate all my energy on few things [Person A]” or “I divide my energy among many things [Person B].” An Optimization subscale item is “I don’t think long about how to realize my plans, I just try it [Person A]” or “I think about exactly how I can best realize my plans [Person B].” An item from the Compensation subscale is “When something does not work as well as before, I get advice from experts or read books [Person A]” or “When something does not work as well as before, I YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 15 am the one who knows what is best for me [Person B].” Affirmative responses are summed to provide a score for each individual on each subscale. The SOC measures have adequate psychometric properties of reliability (e.g., Elective Selection, Cronbach’s alpha = .75-.78; Optimization, Cronbach’s alpha = .68-.76; Compensation, Cronbach’s alpha = .67-.75; Freund & Baltes, 2002). Freund and Baltes (2002) report that SOC has good convergent and divergent associations with other psychological constructs (e.g., goal pursuit, thinking styles) and positive correlations with measures of well-being (Brandtstädter & Renner, 1990; Freund & Baltes, 2002). Positive Youth Development (PYD). A PYD score (ranging from 0 to 10) for each participant was computed at Grade 10 as the mean of the scores for each of the Five Cs (Competence, Confidence, Connection, Character, and Caring, also ranging from 0-10), provided that at least three of the Cs have valid values (in past research, a range of 0 to 100 was used; Phelps, et al., 2009). Higher scores represent higher levels of the Five Cs and therefore, higher levels of PYD. In the 4-H data set, the Cronbach’s alpha for Grade 10 PYD is .77. The Five Cs comprising the PYD construct are operationalized as follows: Competence is a positive view of one’s action in domain-specific areas including the social and academic domains (11 items for Grade 10). In the 4-H data set, the Cronbach’s alpha for Competence in Grade 10 is .64. Confidence is an internal sense of overall positive self-worth, identity, and feelings about one’s physical appearance (16 items for Grades 10). In the 4-H data set, the Cronbach’s alpha for Grade 10 Confidence is .83. YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 16 Character involves respect for societal and cultural rules, possession of standards for correct behaviors, a sense of right and wrong, and integrity (20 items for Grade 10). In the 4-H data set, the Cronbach’s alpha for Grade 10 Character is .71. Connection involves a positive bond with people and institutions that are reflected in healthy, bidirectional exchanges between the individual and peers, family, school, and community in which both parties contribute to the relationship (22 items for Grade 10). In the 4H data set, the Cronbach’s alpha for Grade 10 Connection is .70. Caring is the degree of sympathy and empathy, i.e., the degree to which participants feel sorry for the distress of others (9 items for Grade 10). In the 4-H data set, the Cronbach’s alpha for Grade 10 Caring is .83. Full details about these measures, their construction, and validity and reliability can be found in Lerner et al. (2005) and Bowers et al. (2010). Contribution. Youth responded to 12 items, which were weighted and summed to create two subscales, action and ideology. The Contribution items are derived from existing instruments with known psychometric properties and used in large-scales studies of adolescents, i.e., the Profiles of Student Life-Attitudes and Behaviors (PSL-AB; Benson, Leffert, Scales, & Blyth, 1998) survey and the Teen Assessment Project (TAP; Small, & Rodgers, 1995) survey question bank. Items from the leadership, service, and helping scales measured the frequency of time youth spent helping others (e.g., friends or neighbors), providing service to their communities, and acting in leadership roles. Together, the leadership, service, and helping subsets comprise the action component of Contribution. The ideology scale measured the extent to which Contribution was an important facet of their identities (e.g., ‘It is important to me to contribute to my community and society’). The action and ideology components are weighted equally to calculate YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 17 the Contribution scores. As with the PYD scores, in this study, the Contribution scores range from 0 to 10 (in past research, a range of 0–100 was used; Jeličič, Bobek, Phelps, Lerner, & Lerner, 2007). In the 4-H data set, the Cronbach’s alpha for Grade 10 for Contribution is .80. Results The present research explored how youth strengths, as operationalized by SOC, may be linked to the contextual asset of participation in youth development programs within and across time (Grades 8 and 9). We hypothesized that the coupling of intentional self-regulation skills and YD program participation in Grades 8 and 9 would constitute a relational structure linked to PYD and Contribution in Grade 10. Preliminary Analyses Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations for the measures of youth development program participation (number of programs and intensity of participation), SOC (selection, optimization, and compensation), PYD, and Contribution across Grades 8 to 10 for the 895 youth who participated in the study for at least two of the three grades. As seen in Table 2, there is little change across Grades 8 to 10 in the mean levels of these measures. ----------------------------------------Insert Table 2 about here ----------------------------------------Youth Development Program Participation and SOC Predicting PYD and Contribution Using LISREL 8.80 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2006), a series of structural equation models were tested to examine the relationship between youth development program participation and intentional self-regulation skills at Grades 8 and 9 in predicting Grade 10 PYD and Contribution. To test these relationships, we began by examining a “baseline” model (Model 1) testing the YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 18 influence of YD program participation and SOC across time in predicting Grade 10 PYD and Contribution (see Figure 1). In the next model (Model 2), we added the relationship across time between YD participation and SOC skills in predicting PYD and Contribution (see Figure 2). Both Model 1 and Model 2 included correlations of the residual variance between selection, optimization, and compensation over time (Grades 8 to 9) as well as between Competence and Confidence, and Caring and Character at Grade 10. These estimations were based on theoretical understanding of and previous empirical research with these constructs (Bowers et al., 2010) and, as well, on the relatively high correlations between these indicators. Model 3 was then created to improve on Model 2 by additionally estimating the correlations of residual variance among all of the Five Cs indicators as well as among selection, optimization, and compensation within-time, as suggested in the modification indices (see Figure 3). We evaluated the models using the RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) with a 90% confidence interval as a recommended measure of fit (Steiger & Lind, 1980), with a value of 0.08 or less indicating an adequate fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). In addition, we used the CFI (Comparative Fit Index) and TLI (Tucker-Lewis Index; Tucker & Lewis, 1973) measures, both with a recommended “acceptable” fit at 0.90 and above (McDonald & Ho, 2002). The commonly used χ2 statistic is presented, although it is sensitive to large sample size as is the case in this study (Bollen, 1989). Table 3 presents and compares model fit statistics for all three models. ----------------------------------------Insert Table 3 about here ----------------------------------------- YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 19 The first baseline model (see Figure 1) indicated that while YD participation did not predict Grade 10 PYD, SOC scores in Grade 8 predicted SOC scores in Grade 9, which did appear to predict PYD in Grade 10. In addition, there appears to be a significant pathway between YD program participation in Grade 9 and Grade 10 Contribution, as well as between Grade 9 SOC and Grade 10 Contribution. This model has only mediocre fit (RMSEA=0.09; TLI=0.88; see Table 3 for full model statistics), indicating that there are further relationships among the variables that this baseline model does not account for. ----------------------------------------Insert Figure 1 about here ----------------------------------------Model 2 (see Figure 2), which estimated the relationship between YD participation and SOC in predicting youth thriving, indicated that when accounting for this relationship, YD participation at Grades 8 and 9 still did not predict PYD at Grade 10, although SOC scores in Grades 8 and 9 did continue to predict PYD in Grade 10. In addition, both YD participation and SOC predicted Grade 10 Contribution over time, although there did not appear to be a significant relationship between the two variables in predicting Grade 10 PYD or Contribution. However, the fit for Model 2 did not improve significantly from Model 1 (see Table 3). ----------------------------------------Insert Figure 2 about here ----------------------------------------In order to improve model fit, the third model (see Figure 3) estimated the residuals suggested in the modification indices that were theoretically-relevant and interpretable (i.e., among the Five Cs indicators and among the within-time selection, optimization, and YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 20 compensation scores). These modifications improved the model fit significantly (see Figure 3 for χ2, RMSEA, CFI, and TLI model fit statistics). Similar to the previous models, Model 3 indicated a direct relationship between SOC at Grade 9 (but not YD participation) in predicting overall Grade 10 PYD, as well as significant pathways between both YD participation and SOC in Grade 9 in predicting Grade 10 Contribution. However, this model also suggested that there was a positive relationship between Grade 8 YD participation and Grade 9 SOC (higher YD participation was associated with higher SOC skills), which, in turn, predicted higher Grade 10 PYD and Contribution scores, providing support for our hypothesis of a mutually influential relationship between these two individual and contextual assets. ----------------------------------------Insert Figure 3 about here ----------------------------------------The models tested suggest several potential pathways to youth thriving (indexed by PYD and Contribution in Grade 10), as predicted by youth development program participation and intentional self-regulation skills at Grades 8 and 9. Consistent with previous research (e.g., Gestsdóttir & Lerner, 2007), intentional self-regulation skills across Grades 8 and 9 predicted Grade 10 PYD, providing further support for the importance of these self-regulation skills in promoting positive developmental outcomes in adolescence. However, it did not appear as though participation in youth development programs at Grades 8 and 9 was directly predictive of Grade 10 PYD. However, both YD participation and SOC scores at Grade 8 and 9 did, in fact, predict Grade 10 Contribution, a key outcome of PYD. In addition, Model 3 indicated that Grade 8 YD program participation predicted Grade 9 SOC skills, which, in turn, were predictive of Grade 10 YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 21 PYD and Contribution. This finding supports the hypothesis that the ecological asset of youth development program participation is associated with the individual asset (strength) of intentional self-regulation skills in predicting youth thriving. Furthermore, this finding suggests that participating in YD programs may in fact positively affect a youth’s SOC skills, which, in turn, are predictive of positive developmental outcomes. Discussion Extant research points to the importance of youth development program participation (Theokas & Lerner, 2006; Urban, Lewin-Bizan, & Lerner, 2009, 2010) and self-regulatory behaviors (Gestsdóttir & Lerner, 2007) as contextual and individual assets, respectively, for promoting positive development among adolescents. Accordingly, the present study aimed to further elucidate the relationship between YD program participation and intentional selfregulation skills. We predicted that the individual characteristics of intentional self-regulation, as operationalized by the selection (S), optimization (O), and compensation (C) measure (Freund & Baltes, 2002), would, when coupled with the contextual asset of participation in YD programs (operationalized by number of programs and intensity of participation), be linked to PYD and Contribution in Grade 10. The results provided some support for the hypothesis that there is an important relationship between the ecological asset of youth development programs and the individual strength of intentional self-regulation skills. Furthermore, it appears as though there is directionality in that relationship; youth development program participation at Grade 8 was predictive of Grade 9 SOC skills, which, in turn, were predictive of Grade 10 PYD and Contribution. However, the results suggest that, contrary to suggestions in the literature (e.g., Benson et al., 1998) and to our hypothesis, there was no direct relationship between YD program YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 22 participation at Grades 8 and 9 and PYD at Grade 10. While SOC skills at Grades 8 and 9 positively predicted Grade 10 PYD, this direct relation did not exist for Grade 8 and 9 YD program participation. These findings suggest a more nuanced link between intentional self-regulation skills and YD program participation than suggested in past research. There was evidence for a relationship between the contextual resource of YD program participation at Grade 8 and the individual asset of SOC skills in Grade 9 and, in turn, Grade 9 SOC skills predicted Grade 10 PYD and Contribution. In addition, there was a direct relationship between Grade 8 and 9 YD participation and Grade 10 Contribution. However, there was no evidence for a direct relationship between YD participation and Grade 10 PYD. This finding does make conceptual sense, given that Contribution is often a key outcome for youth development programs, and service to one’s community may be a value that is highlighted specifically within the program context (National 4-H Council, 2010). Therefore, for youth participating in YD programs, Contribution may be a specific outcome directly related to program curricula, instead of an outcome of general thriving as conceptualized in the PYD model. Furthermore, it appears as though participation in a YD program is positively related to SOC skills. The ability to select goals, optimize resources in the environment to achieve these goals, and then compensate when problems arise would seem to be relevant skills relating to youth contribution to family, community, and self. Limitations and Future Research The selective subsample used in this research provides limitations for generalizing the results of this study. The subsample included only youth who participated in the study for at least two consecutive years, and such youth are likely to be similar in other characteristics. Moreover, the indices reflecting participation in a YD program indicated relatively low participation in the YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 23 sample (see Table 2), and participation level variance may have constrained the degree to which we were able to identify the potential impacts of participation in such a program. In addition, this study used a general measure to index positive youth development, and it may be useful for future research to examine the impact of the relationship between youth development program participation and intentional self-regulation skills in promoting domain-specific outcomes. Programs vary, of course, in their behavioral objectives, and obtaining more nuanced information about what specific facets of intentional self-regulation are linked to what specific outcomes for particular YD programs may enhance program design and sharpen program evaluations. Furthermore, the present research did not examine trajectories of positive developmental outcomes, an assessment that would be useful to further understanding the nature of the relationship between YD participation and SOC skills in promoting youth thriving. In addition, while the current research highlights the important developmental impacts that involvement in a YD program may have on youth, and suggests the use of the general principles that are necessary to encourage positive outcomes (i.e., the Big Three; Lerner, 2004), it is critical to note that the specific aspects of such programs that provide these impacts are not discernible within the current data set. Within the survey method of the 4-H Study data set, the specific features of any given instance of the YD programs in which participants engaged were not assessed. As such, these programs constitute a “black box.” Each individual program may have a different theory of change, and the activities and relationships within programs certainly encompass many domains. Furthermore, even programs that have a general guiding structure at the national level (e.g., 4-H programs, Big Brothers/Big Sisters, Scouts) may not enact these protocols with high fidelity in individual settings. Therefore, there may be considerable variance at the local level in programmatic practices. In order to meet the needs of individual YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 24 communities, programs evolve within their organization’s guidelines to fit their personal needs and constraints. In fact, even when programs delineate specific procedures and guidelines, that does not necessarily mean that such guidelines are actually put into practice. Therefore, our two indicators of YD participation (number of programs and intensity of participation) certainly do not capture the full breadth and depth of experiences that youth have in such programs. The variance among YD programs presents a unique methodological challenge when attempting to ascertain the specific aspects of various programs that are associated with developmental outcomes. The methodology of the 4-H Study is not best suited to make transparent the contexts of a given program (“black box”). Therefore, it will be important in future research to use detailed qualitative, process-oriented information about individual programs in order to fully test outcome-oriented research questions. Future research must delve deeper into the individual practices of programs to explore both the framework for such programs and also what actually happens in terms of implementation. Conclusions The results of this research provide support for the notion that a convergence of contextual and individual assets is critical in promoting positive developmental outcomes for adolescents. The findings of this study have important policy and program implications, suggesting that participation in high quality YD programs may be an especially important resource for youth in developing individual strengths, such as self-regulatory skills, and that the alignment of program resources and youth strengths may be critical in promoting positive developmental outcomes. These findings begin to provide insight into the relationship between individual and contextual assets, and suggest the need for future research to address these YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation complex relationships in a nuanced way using longitudinal data from diverse populations of adolescents. 25 YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 26 References Balsano, A. B., Phelps, E., Theokas, C., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2009). Patterns of early adolescents’ participation in youth development programs having positive youth development goals. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19(2), 249-259. Barber, B. L., Stone, M. R., Hunt, J. E., & Eccles, J. S. (2005). Benefits of activity participation: The roles of identity affirmation and peer group norm sharing. In J. L. Mahoney, R. W. Larson & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Organized activities as contexts of development: Extracurricular activities, after-school and community programs (pp. 185-210). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. Benson, P.L., Leffert, N., Scales, P.C., & Blyth, D.A. (1998). Beyond the ‘‘village’’ rhetoric: Creating healthy communities for children and adolescents. Applied Developmental Science, 2(3), 138–159. Bollen, K. A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: Wiley. Bowers, E. P., Li, Y., Kiely, M. K., Brittian, A., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2010). The Five Cs model of positive youth development: A longitudinal analysis of confirmatory factor structure and measurement invariance. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 720-735. Brandtstädter, J. & Renner, G. (1990). Tenacious goal pursuit and flexible goal adjustment: Explication and age-related analysis of assimilative and accommodative strategies of coping. Psychology and Aging, 5(1), 58-67. Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In K. A. Bollen & J.S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA: Sage. YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 27 Deschenes, S., McDonald, M., & McLaughlin, M. (2004). Youth organizations: From principles to practice. In S.F. Hamilton & M.A. Hamilton (Eds.), The Youth Development Handbook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Eccles, J. S., & Gootman, J. A. (Eds.). (2002). Community programs to promote youth development: Committee on community-level programs for youth. Washington DC: National Academy Press. Erikson, E.H. (1968). Identity: youth and crisis. Oxford, England: Norton & Co. Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2005). Developmental benefits of extracurricular involvement: Do peer characteristics mediate the link between activities and youth outcomes? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(6), 507-520. Freud, A. (1969). Adolescence as a developmental disturbance. In G. Caplan & S. Lebovici (Eds.), Adolescence (pp. 5-10). New York: Basic Books. Freund, A. M., & Baltes, P. B. (2002). Life-management strategies of selection, optimization and compensation: Measurement by self-report and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 642-662. Gestsdóttir, S., & Lerner, R. M. (2007). Intentional self-regulation and positive youth development in early adolescence: Findings from the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development. Developmental Psychology, 43, 508-521. Gestsdóttir, S., & Lerner, R. M. (2008). Positive development in adolescence: The development and role of intentional self-regulation. Human Development, 51, 202-224. Gestsdóttir, S., Lewin-Bizan, S., von Eye, A., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2009). The structure and function of selection, optimization, and compensation in middle YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 28 adolescence: Theoretical and applied implications. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(5), 585-600. Hall, G. S. (1904). Adolescence: Its psychology and its relations to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education (Vols. 1 and 2). New York: Appleton. Hauser, R. M., & Featherman, D. L. (1976). Equality of schooling: Trends and prospects. Sociology and Education, 49, 99-120. Jeličič, H., Bobek, D.L., Phelps, E., Lerner, R.M., & Lerner, J.V. (2007). Using positive youth development to predict contribution and risk behaviors in early adolescence: Findings from the first two waves of the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31, 263–273. Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (2006). LISREL 8.8. Chicago: Scientific Software International. King, P. E., Dowling, E. M., Mueller, R. A., White, K., Schultz, W., Osborn, P., Dickerson, E., Bobek, D. L., Lerner, R. M., Benson, P. L., & Scales, P. C. (2005). Thriving in adolescence: The voices of youth-serving practitioners, parents, and early and late adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 94-112. Larson, R. W. (2000). Toward a psychology of positive youth development. American Psychologist, 55(1), 170-183. Lerner, J. V., Phelps, E., Forman, Y., & Bowers, E. P. (2009). Positive youth development. In R. M. Lerner, & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of Adolescent Psychology: Vol 1. Individual bases of adolescent development, (3rd ed., pp.524-558). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Lerner, R. M. (2004). Liberty: Thriving and civic engagement among American youth. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 29 Lerner, R. M. (2005). Promoting Positive Youth Development: Theoretical and Empirical Bases. White paper prepared for the Workshop on the Science of Adolescent Health and Development, National Research Council/Institute of Medicine. Washington, D.C.: National Academies of Science. Lerner, R. M. (2009). The positive youth development perspective: Theoretical and empirical bases of a strength-based approach to adolescent development. In C. R. Snyder and S.J. Lopez (Eds.). Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (2nd ed.) (pp. 149-163). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. Lerner, R. M., Freund, A. M., De Stefanis, I., & Habermas, T. (2001). Understanding developmental regulation in adolescence: The use of the selection, optimization, and compensation model. Human Development, 44, 29-50. Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., Almerigi, J., Theokas, C., Phelps, E., Gestsdóttir, S. Naudeau, S., Jeličič, H., Alberts, A. E., Ma, L., Smith, L. M., Bobek, D. L., Richman-Raphael, D., Simpson, I., Christiansen, E. D., & von Eye, A. (2005). Positive youth development, participation in community youth development programs, and community contributions of fifth Grade adolescents: Findings from the first wave of the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development. Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 17-71. Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., & Phelps. E. (2008). The positive development of youth: Report of the findings from the first four years of the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development. Institute for Applied Research in Youth Development, Tufts University: Medford, MA. Lerner, R. M., Lerner, J. V., & Phelps, E. (2009). Waves of the Future: The first five years of the 4-H study of positive youth development. Institute for Applied Research in Youth Development, Tufts University: Medford, MA YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 30 Li, Y., Bebiroglu, N., Phelps, E., & Lerner, R. M. (2009). Out-of-school time activity participation, school engagement and positive youth development: Findings from the 4-H study of positive youth development. Journal of Youth Development. doi: 080303FA001. Mahoney, J. L., Larson, R. W., Eccles, J. S., & Lord, H. (2005). Organized activities as development contexts for children and adolescents. In J. L. Mahoney, R. W. Larson & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Organized activities as contexts of development: Extracurricular activities, after-school and community programs. (pp. 3-22). Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. Mahoney, J. L., Vandell, D. L., Simkins, S., & Zarrett, N. (2009). Adolescent out-of-school activities. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of Adolescent Psychology: Vol 2. Contextual influences on adolescent development (3rd ed., pp. 228-269). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M. H. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64-82. Mueller, M. K., Lewin-Bizan, S., & Urban, J. B. (In press). Youth activity involvement and positive youth development. In R. M. Lerner, J. V. Lerner, & J. B. Benson, (Eds.), Advances in Child Development and Behavior: Positive youth development: Research and applications for promoting thriving in adolescence. Elsevir Publishing. National 4-H Council. (2010) 4-H Today: Five National Initiatives. Retrieved from http://www.4-H.org. Overton, W. F. (2010). Life-span development: Concepts and issues. In R. M. Lerner (Ed-inchief) & W. F. Overton (Vol. Ed.), The Handbook of Life-Span Development: Vol 1. Cognition, Biology, and Methods (pp. 1-29). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 31 Phelps, E., Balsano, A., Fay, K., Peltz, J., Zimmerman, S., Lerner, R., M., & Lerner, J. V. (2007). Nuances in early adolescent development trajectories of positive and of problematic/risk behaviors: Findings from the 4-H Study of Positive Youth Development. Child and Adolescent Clinics of North America, 16(2), 473–496. Phelps, E., Zimmerman, S., Warren, A. E. A., Jeličič, H., von Eye, A., & Lerner, R. M. (2009). The structure and developmental course of Positive Youth Development (PYD) in early adolescence: Implications for theory and practice. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(5), 571-584. Rhodes, J.E. (2002). Stand by me: The risks and rewards of mentoring today’s youth. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Roth, J. L., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2003). What exactly is a youth development program? Answers from research and practice. Applied Developmental Science, 7, 94-111. Sherrod, L. R., & Lauckhardt, J. (2009). The development of citizenship. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Vol 2. Contextual influences on adolescent development, (3rd ed., pp. 372-407). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Small, S., & Rodgers, K. (1995). Teen assessment project. Madison, WI: School of Family Resources and Consumer Sciences, University of Wisconsin. Steiger, J.H., & Lind, J.M. (1980). Statistically based tests for the number of common factors. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Psychometric Society, Iowa City, IA. Stoneman, D. (2002). The role of youth programming in the development of civic engagement. Applied Developmental Science, 6, 221-226. YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 32 Theokas, C., & Lerner, R. M. (2006). Observed ecological assets in families, schools, and neighborhoods: Conceptualization, measurement and relations with positive and negative developmental outcomes. Applied Developmental Science, 10(2), 61-74. Tucker, L. R., & Lewis, C. (1973). A reliability coefficient for maximum likelihood factor analysis. Psychometrika, 38(1), 1-10. Urban, J. B., Lewin-Bizan, S., & Lerner, R. M. (2009). The role of neighborhood ecological assets and activity involvement in youth developmental outcomes: Differential impacts of asset poor and asset rich neighborhoods. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(5) 601-614. Urban, J.B., Lewin-Bizan, S. & Lerner, R.M. (2010). The role of intentional self regulation, lower neighborhood ecological assets, and activity involvement in youth developmental outcomes. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(7), 783-800. doi:10.1007/s10964-0109549-y Zaff, J. F., Hart, D., Flanagan, C. A., Youniss, J., & Levine, P. (2010). Developing civic engagement within a civic context. In R. M. Lerner (Ed-in-chief), M. E. Lamb, & A. M. Freund (Vol. Eds.), The Handbook of Life-Span Development: Vol 2. Social and Emotional Development (pp. 590-630). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. Zaff, J. F., Moore, K. A., Papillo, A. R., & Williams, S. (2003). Implications of extracurricular activity participation during adolescence on positive outcomes. Journal of Adolescent Research, 18, 599-630. Zarrett, N., Fay, K., Carrano, J., Li, Y., Phelps, E., & Lerner, R. M. (2009). More than child’s play: Variable- and pattern-centered approaches for examining effects of sports participation on youth development. Developmental Psychology. 45(2), 368-382. YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation Zarrett, N., Peltz, J., Fay, K., Li, Y., & Lerner, R. M. (2007). Sports and youth development programs: Theoretical and practical implications of early adolescent participation in multiple instances of structured out-of-school (OST) activity. Journal of Youth Development, 2 doi: 0702FA001 Zimmerman, S., Phelps, E., & Lerner, R. M. (2007). Intentional self-regulation in early adolescence: Assessing the structure of selection, optimization, and compensations processes. European Journal of Developmental Science, 1, 272-299. Zimmerman, S., Phelps, E., & Lerner, R. M. (2008). Positive and negative developmental trajectories in U.S. adolescents: Where the PYD perspective meets the deficit model. Research in Human Development, 5,153-165. 33 YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 34 Table 1. Percentage of grade and variable (VN) non-response for each variable within each grade Grade 8 Grade 9 Grade 10 Percentage of grade non-response in overall sample* 54.4 73.6 45.3 Percentage of grade non-response in subsample** 20.1 18.2 33.9 VN*** Overall** VN*** Overall** VN*** Overall** YD program participation 3.2 22.7 4.1 21.6 2.9 35.8 Selection 7.4 26.0 6.4 23.5 8.5 39.4 Optimization 7.7 26.3 6.2 23.2 8.8 39.7 Compensation 9.7 27.8 7.8 24.6 10.1 40.6 Positive Youth Development (PYD) 2.2 21.9 10.0 26.4 1.4 34.7 Contribution 5.7 24.7 5.2 22.5 5.4 37.4 *Percentages were calculated based on the overall sample size for youth who participated at least once in Grades 8 to 10 (N = 4282). **Percentages were calculated based on the longitudinal subsample of youth in the current study (youth who participated at least two times in Grades 8 to 10, N = 895) ***Percentages were calculated based on the sample size for each particular wave of data for the longitudinal subsample of youth in the current study (youth who participated at least two times in Grades 8 to 10): Ng8 = 715, Ng9 = 732, and Ng10 = 592. YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 35 Table 2. Mean, standard deviation, and range for each variable within each grade for subsample of youth who participated in at least two grades (N=895). Grade 8 Grade 9 Grade 10 M SD N M SD N M SD N Scale range Number of YD programs 0.49 0.80 715 0.44 0.80 732 0.40 0.71 592 0-6 Intensity of YD participation 0.76 2.09 692 0.69 1.95 702 0.53 1.64 575 0-20 Selection 2.80 1.34 662 2.70 1.42 685 2.63 1.41 542 0-6 Optimization 3.97 1.24 660 4.21 1.41 687 4.15 1.33 540 0-6 Compensation 3.55 1.25 646 3.61 1.29 675 3.48 1.26 532 0-6 PYD 6.78 1.21 699 6.85 1.30 659 6.87 1.20 584 0-10 Contribution 5.64 1.66 674 5.65 1.69 694 5.71 1.70 560 0-10 YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 36 Table 3. Model Fit Statistics Model Model 1 Description RMSEA χ2 (df) χ2∆ (df ∆) (90% CI) CFI TLI 870.20 (108) --- 0.09 0.91 0.88 0.91 0.88 0.93 0.90 Baseline model testing direct paths between YD participation and SOC to PYD and Contribution Model 2 (0.083-0.094) Structural model testing relationship between YD participation and SOC in 870.80 (106) 0.06 (2) predicting PYD and Contribution Model 3 0.09 (0.084-0.095) Final structural model, improvements made by estimating theta epsilons with large standardized residuals 651.89 (95) 218.91* (11) 0.08 (0.075-0.087) Note: Significant χ2 test indicates that the model listed had a significantly better fit than the previous model at the p<.001 level. YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation Figure 1. Baseline structural model (Model 1) with standardized parameter estimates for youth development program participation and intentional self-regulation skills at Grades 8 and 9 predicting PYD and Contribution at Grade 10. 37 YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 38 Figure 2. Structural model (Model 2) with standardized parameter estimates for the relationship between youth development program participation and intentional self-regulation skills at Grades 8 and 9 predicting PYD and Contribution at Grade 10. YD Participation and Intentional Self-Regulation 39 Figure 3. Improved fit final structural model (Model 3) with standardized parameter estimates for the relationship between youth YD program participation and intentional self-regulation skills at Grades 8 and 9 predicting PYD and Contribution at Grade 10.