Jane Mansbridge interview

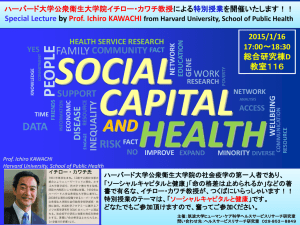

advertisement

CHAPTER 22 JENNY JFK SCHOOL Transcribed by Jenny Choi Q. Why don’t we start by having you tell us a little bit about yourself and how you came into academics because that’s always interesting. Well I came from an era in which a lot of women didn’t go into academia. So I had no intention of going into academia. I was planning to have four children, maybe five, and that was that. So it was really an accident that I came into academia. I had quite good grades and my husband was going to graduate school. He said why don’t I apply for the same fellowship that he had applied for and why don’t I go to graduate school. My thought was that I’d be following him and so I said, “Fine, I’ll apply to graduate school.” So I got a full scholarship and got into Harvard for graduate school. I just ended up in graduate school. But out of my closest group of six friends, only two of them had any plans to go on to graduate school. This was in 1961, so it was before the women’s movement. Considerably before the women’s movement. When even the inklings of the women’s movement had not started. I had, through a series of pieces of luck, been able to go to a girls’ school. I had mostly attended public school, but for six months, I went to a girls’ school in Europe. Suddenly I realized how freeing it was and so when it came time to look for colleges and universities, I had decided to go to a girls’ school, or a women’s college as they call it these days. But when I came here [Radcliffe], I realized that this was not a women’s college. This was a men’s college that had women attached. And the women were dressed. It wasn’t so much that they wore pearls, but it was very clear to me that they had spent thought on their clothes....For example, I would wear my gym suit at Wellesley most of the time because it was made of some kind of material like steel and it didn’t require ironing or anything like that. So I wore a gym suit and jeans, and if it was cold, a sweater top. That wasn’t the way that the young women were at Radcliffe. But the point was that I really felt, during the week, free to just read and write papers, and read more and write more papers, and read and just immerse myself in the life of books and ideas. Q. But you’re saying your expectation after having gone there was having four children. Yes, so I wanted to be a well-rounded person. I also just had lots of interests, so I took college as a time when I could do that kind of thing. To some degree, the fact that I didn’t take myself seriously was a bonus as well as a negative. Because it meant that when I did my first [major academic] work, I didn’t think at all about whether it would get me articles or it would get me far in the profession. I just wanted to be useful and I wanted to come up with useful findings. I think that made the book much better. The book would never have been written if I had tried to advance myself in the profession because it was too orthogonal to what was being done at the time. Q. Do you think a lot of women have that attitude? Now? I have no idea. Then, yes absolutely. It was like being an “amateur.” A little like being in the Renaissance and being a rich man, you could enjoy the work for the work’s sake. So that was a good side of it. Q. So was it Sandy who really encouraged you? Oh no, it was my first husband. Q. So he was really a critical person. It wasn’t so much encouraging me. It was more of, “Well, why don’t you do this?” Encourage sounds like, “This would be the path for you.” It was more like, “I’m going to graduate school, so why don’t you go to graduate school?” It was following my man. But I had to follow him to Harvard graduate school. Q. Who really told you that you could do it then, as a serious thing? That happened incrementally. When I was at the University Chicago -- that was my first job -they were trying to socialize me as an academic and it was taking a little while. That was a very serious, intellectual place and I became socialized to thinking of myself as serious in my first job as a teacher. That’s really quite late in the game. I can speak directly to the seriousness at Chicago. It was a serious intellectual place, and I think it still is in a way that probably no other university in the United States is. It’s just intensely serious, and that’s wonderful! Because if you had a good idea, your idea was a good idea. I don’t mean to say that there wasn’t any sexism. But Chicago was extremely liberating for me. Q. At Chicago, they didn’t care or notice what you looked like, where you were from...They just wanted to talk about your ideas. I think we know from the Implicit Association Test that they did notice (laughter). But they noticed less than most people. Q. I was talking with a woman who had been president of a well-known college, provost of a couple of other top schools. She said that when she went to graduate school in ‘68, they asked her if she were on the pill. No one said anything like that to me, but I wasn’t married. Did you have any experiences like that? I didn’t have that experience, but of course I had many of the experiences of my time. One was that Lamont, the undergraduate library that had all of the books for the courses, was closed to women. That was the center of course life. Widener was for research, but Lamont was for the courses. And women were not allowed in Lamont so we had to go work at Hilles, up in the quad, which is about a twelve minute walk from the Yard and about a ten minute run. I remember once I was giving a paper on Hobbes, and I had left my copy of the Leviathan with my notes in the library. If it was Lamont, I could have just zipped across and gotten it but there was no way I could have gone all the way up to Radcliffe and back. So I just did it all from my head. If you’re doing close textual analysis and you’ve marked the text up, doing it from your head is not so good. You also had to go through the back door for the Faculty Club and you had to be accompanied by a man. So there were lots of external things that were sexist. In regard to my own life, one of the professors that I was working with -- a very nice guy and it was just a mark of the times -- thought incorrectly that I was in some way sexually attracted to him and chased me around the desk, which ended in a very difficult way. I just never took a course from him or anything after that and that changed the direction of my studies a little bit. It wasn’t that he was an evil man at all. In fact I think he was a very nice man. But he completely misunderstood the fact that I’m a fairly friendly person. So that was a real problem. Then just small things like being not called on in seminars and so forth. So l learned a lot of tricks to somewhat overcome those things. One trick was that in the lectures, you take notes as the person’s talking, and you’re the first person to ask the question because there’s often a little space right then after the lecture comes to an end, when the professor asks, “Questions?” And then if you’re more or less in the front row and you raise your hand...I always tell the women to raise their hands without a crook, like a tennis serve, all the way up. If you raise your hand and you’re in the front row, and you do it right after the lecture, then you can be called on. So I learned that that was really the only way to be called on. Then when I got to Northwestern, people loved it because it broke the ice after a lecture. But it was a self-defense technique. Another trick is that in seminars, if you use the word “no” as your introductory word, that’s the best. You certainly don’t say “oh...um...hmm,” but you lean forward and say “No, Kristen,” you can even follow it with “I agree with you.” You can say almost anything, but if you lean forward and say “no” as your introductory word, you have the floor. It’s a really commanding word. It doesn’t actually make a difference what you say afterwards. But you can lead with “no” and say “My other point is x.” People forget that you’ve said “no.” You just have to begin with “no.” Finally, I worked on my voice and I suggest to my friends that they work on their voices. Margaret Thatcher lowered her voice two octaves. If you slow down and lower your voice and make eye contact and project, you will be listened to more than if you just sort of tentatively approach a subject. I think that we do pick up, in the course of day-to-day inter-gender relations, not to do those things. But in a seminar, they are perfectly acceptable. I learned to do them as an absolutely conscious endeavor. Q. One of the things that they talk about is women’s inability to negotiate, to ask for the things that they need. Do you think you ever suffered from that, and if so, how did you get over it? Oh yes, I never negotiated for anything. Of course you know Linda Babcock did that work, which has been built on by Hannah Riley Bowles. Bowles presents male and female managers with two letters from employees that they supposedly just have hired. The letters are slightly obnoxious. The letters are exactly the same, except that one has a woman’s name and the other has a man’s name. But both are slightly obnoxious; they demand a second computer and a parking space, and a and b, and by the end of it, you’re going, “Ugh, who is this person?” Then later she asks whether each manager would like to work with this person. Male managers don’t want to work with the women who made the demands although they are perfectly fine working with a man who made the same demands! Whereas female managers don’t want to work with either because it’s an obnoxious letter. It’s from someone who is not the kind of person you would want to work with. But the men forgive the men because the idea is that men are supposed to be like that. So that’s one reason why women are less likely to negotiate, because they’ve been used to the subtle punishments that come from being aggressive all their lives. So yeah, I’ve never negotiated for a salary or anything like that. Q. It’s viewed as aggressive too. It’s not viewed as being strong. We know from Hannah’s work that it is. You can suspect everything you want, but she did really terrific work with these two letters showing that it’s true. Q. Different images people have though. If men behave in that way, it’s considered a good thing. Whereas women, it’s not viewed in that way. Do you think that has changed? I think so. I think today’s women are somewhat more able to take strong-looking roles. You know Amy Cuddy’s work on body language, in a wonderful TED talk that she gives. I think that today women are a little bit more comfortable playing with a whole range of personalities. They can be this sometimes and be something else sometimes. We felt a little bit more confined. But of course, there’s an awful lot of the same examples that we faced while growing up today. Q. What about handling dual careers? A lot of this is structural. Although, as you said, it’s hard to change institutions. But it’s really critical to change institutions, and the psychology will follow if you will. But in the meantime, before we change the institution, it’s good to have psychological tricks for keeping yourself sane. With regard to dual careers, the institution is not set up for families yet. Academia’s not set up for the fact that your prime childbearing years are right in the middle of the years that you’re trying to get tenure. That was true with me too. I only had one child, but I had him when I was coming up for tenure. It was insane. Some days I really just wasn’t sure that I wouldn’t go crazy. And at one point -- my child was in daycare -- he got colds a lot. When the child got a cold, my husband would get a cold, and then finally, although I was the last to get it, after being exposed to the germs for two weeks -- one from my child and one from my husband -- I would come down with it. So I not only had a cold that academic season, but I had people to take care of beforehand. I remember a male colleague asking me over to supper and I couldn’t come because I had a cold. And he said irritated, “Jenny, you have had colds all winter long!” This is true. But he didn’t have any idea that it might have anything to do with having a baby. But I think we were very lucky with regard to the dual career thing, because Sandy -- my second husband -- had a very good job at Harvard and he was able to figure out a way of coming and being with me at the University of Chicago. When I took my job at the University of Chicago, they asked me if there was anything they could put in my contract to make me want to come. I was just about to say “no,” not being a negotiator, when Sandy told me to ask them to say that I could take every other year off without pay in the contract. I did, and Chicago said yes. And so I had every other year to come back here to Harvard. That’s the only way I got my first book written. Q. Now of course, they have spousal hires. So you could have said that you want your spouse to be hired too. I could have, but in those days...They also didn’t even have insurance for when I had a miscarriage. I had a single person’s insurance, and the insurance didn’t cover a miscarriage. There were a lot of these antediluvian things back in the day. Q. So even though you were married... I wasn’t married. I was single and I had single insurance, but...I thought I was going to have a baby. In fact I had a miscarriage, which was a real trauma. I was extremely upset to find out that my insurance didn’t cover it because the pregnancy was considered voluntary. Q. I’m always amazed at these interviews. I’ve done a number of them by now, and I always find myself going like this (facial expression) or losing it completely. I’m just appalled at some of the things that I’m hearing. I’ve known you for a long time. You always seem to be poised and I’ve looked up to you a lot. Of course you never know what’s going on in the inside, you only see them from the outside. How did you deal with all of these things happening to you? I freaked out. I might have looked poised to you, but I’m sure I looked poised to the people at those seminars too. I won’t say you have to be poised, but if you’re going to get the respect of your peers, you do have to be poised. But oh yeah, I was falling apart inside. I didn’t even tell you that when I was in graduate school, I was raped. That’s the worst thing that ever happened to me. It was a stranger rape. That was very, very difficult, so it was a very long time before I spoke about it. Even today, if you were to look in my purse, you’ll find a whistle. I won’t go anywhere without it when it’s dark. I won’t walk through the Radcliffe yard. It scarred me for life and it certainly was extremely traumatic at the time. We didn’t accept those kinds of things, which is why we had the women’s movement. But that was the water you swam in and the air you breathed. You either dealt with it, or you didn’t. A lot of people didn’t. A lot of people left graduate school, and I was extremely lucky that I happened to have work that I thought was galvanizing and that I wanted to do. And there were some truly lucky breaks, like the University of Chicago, that came my way. So it wasn’t just force of personality. I’m not one of the stronger people I know. Q. Do you rely on friends? Did you parents help a great deal? I didn’t tell them about the rape, because I knew my mother would tell me that I would have to go into an apartment building with a doorman and all that stuff. It would have worried her life away. I never told either of my parents. This is the kind of thing you don’t tell many people. I remember during the women’s movement, there was a speak-out at Northwestern and I spoke publicly about this. It was very difficult. I was trembling the whole time I did it. Q. Did it help to talk about these things with other people? If you’re talking about the rape, no, I didn’t talk about it with many people at all. Q. Some of the other issues, though... No, I don’t think I did it very much. Because if you think, I went to graduate school in ‘61 and the women’s movement wasn’t until ‘68. So there weren’t people talking about these things. The whole idea of even having a strategy to deal with a seminar...you wouldn’t have thought that. There wasn’t that kind of instrumental approach. There wasn’t the critique. There weren’t the tools. There weren’t the intellectual tools to even understand what was going on! Here’s a wonderful example. I ended up in political science, but I went to graduate school in history, which was what I majored in at college. It turns out I’m sort of dyslexic in numbers so dates are very hard for me, even though dates are the anchor in history. So I was very nervous trying to do history and not being able to remember dates. That nervousness carried over to a lot of nervousness and I flunked my generals. So I have an MA in history. Sort of a booby prize kind of MA. But I flunked the generals so badly that they told me they were thinking of not letting me take them again. Can you imagine that? That is not done. It’s never even heard of. You always get to take them again if you flunk them. So I moved into political science... Now what was the question? I’m getting lost in the horror of flunking my generals. One of the reasons I did fail, besides being dyslexic in numbers, was that I was doing the second shift. I wasn’t really part of my graduate school cohort... I wasn’t picking up the code words. So if there was a book on the reading list, I read it from beginning to end without knowing what I was supposed to be looking for. Now time has winnowed out the key concepts in some of these books, so when you think of Schumpeter, you think of creative destruction, etc. You look within the books for the things that have lasted. But I was just reading every word equally because I wasn’t part of the cohort that was talking about the stuff in the book. That was because I was home, cooking, shopping, and putting supper on the table. I wasn’t there as part of the cohort. There are a lot of subtle ways in which it was even more difficult for women in those days than it is now for women. Q. I think sometimes women don’t make themselves part of the cohort. You need somebody to offer them an invitation and bring them in. But I’ve been struck by how many people I’ve talked with...Suzanne Rudolph told me that she wanted to be offered a research assistant’s job and no one offered it to her. So she finally went up to the professor and asked if she could be an RA. He told her he hadn’t offered one to her because – I think I remember this correctly -- “Well, I didn’t think you wanted job because you didn’t ask.” It’s the title of Linda Babcock’s book: Women Don’t Ask. A black friend once said to me that at all of the parties she had gone to, no one came and introduced themselves. I thought to myself, “My god, I wouldn’t go up and introduce myself.” At parties, I look for the people I know and talk to them. I don’t go around to people I don’t know and introduce myself. But she really felt it. So from then on, when I go to parties, I‘ve made a point of doing that if there’s someone who’s not seeming to be talking to anybody, particularly if they’re African-American or part of some group that might be marginalized within that context. I do that because I think you’re right, we don’t ask. Q. There are a lot of women or men who have gone through situations and it’s a tough initiation. Their attitude is, “Boy, it was tough for me. I’m going to make it tough for you.” Other people are different, saying, “Wow, that was really hard. I’m never going to do that to anybody else.” What is it that causes some people to do that and others not? I don’t know. There might be different things in people’s family background. But I think the women’s movement did help us all see how tremendously important it was to be there for one another. The women’s movement has made a huge difference in my life, just in terms of giving me the analytic tools and a vision of community and of helping each other out and keeping an eye out for one another and going the extra mile for one another. That’s really important. After graduate school, everywhere in academia I’ve gone, the women’s movement had happened by then, so there was always a community of women. Q. I think you helped make it happen. You were there for a lot of women. You weren’t just a casual observer, you were part of it. There were a lot of us though. That’s the whole thing about a movement. It really is lots and lots and lots of people working together. My recent work, which I haven’t had the time to write up, is based on interviews with working class women, asking them their views about relationships between women and men.. In the course of their talking about things, you see the tiny moves each of them have made, like calling their boss a male chauvinist, etc. This is in the early 90s. Things that were little risks, people managed to do, and help others to do. It will take a long time to get full equality. We’re seeing quite a few educated women dropping out of the paid labor force and these things have social consequences. These things aren’t just about individual choices. I totally support anyone’s right to make her own decision to do not be in the paid labor force. I really think that the vocation of homemaker is an important vocation. But it is true that what one person does then affects what another person does. What the majority does in particular affects what others in the group do. Social meanings get created by all of our smallest gestures. (Gesturing to research assistants in room.) You all being here and doing this, this is cementing something in your lives. I don’t know what it’s cementing, but it’s just a little bit of a thumb on the scale, a little bit more of the experiences that you’re having that will change you. If we weren’t doing something like this, you would have never run into anybody who cared about women’s roles in society or was thinking about their place in academia. That would mean a very different thing for the way you grow up. It would be great if one day, nobody was thinking about this at all because there was need for it. Q. What can universities do that would make things better for women? If you want to talk specifically about Harvard since that’s where you are, that’s fine. But universities in general. There’s a whole range of options, as you and I know, that some universities take and others don’t. Well, the first major thing that you can do is provide some sort of support for childcare. And parental leave has to be automatic, it shouldn’t be asked for, and it should be much longer than it presently is. Q. How long is it at Harvard? Oh, I don’t know; I was on the task force that got it increased. I think -- you’re supposed to know this too, Kristen -- maybe it’s a semester? I think it may be a semester. We’ve got it so it doesn’t have to be taken just when the baby is born. But a semester’s a drop in the bucket and that’s what the men have to be taught. Because they say, “Oh well, you’ve got a semester and that takes care of that! Now the playing field’s even.” No! Guess what? Kids grow up and it’s just as tough as having a baby sometimes, until they’re 18 or so, in different ways. So the idea that you just get a semester off and now you’re right back up there with everybody else just isn’t the case. I think we need to do a lot of conscious raising around that as well as changing those structures. Take Frank Dobbin’s work in sociology, looking at Fortune 500 companies over time. He shows that creating a position with responsibility for diversity makes a real difference. He found that actual increases in women and in African-Americans and Latino/Latinas come from having someone have responsibility for this, or at least having some kind of committed task force. We need to do that in academia. We shouldn’t just have someone at the vice provost level, but somebody at every department, a faculty member, whose job it is to think about the issues of women’s advancement and the advancement of minorities in the department. We know from Frank’s work that by giving responsibilities to a particular person, or even better yet, a person and a committee -- that would be ideal -- then things happen and they happen in an informed, local-knowledge way, instead of the university laying down some law. It’s through figuring out how things work within this culture that you nurture talent. The local culture is important. For example, mentoring programs that are put in from above don’t work terribly well. But mentoring programs that are thought out by the people on the ground do work, and they work much better. So those are a couple of things. VP: you’re talking about having a semester off. Is that paid or unpaid? It’s paid. But earlier I took all those semesters off unpaid. I even got that put in my contract. That’s something I say to all young people, particularly to women. Whenever you negotiate for anything, negotiate for time. Always trade money for time. Live on Cheerios, wear the same sweatshirt day in and day out, and take all your money and pay for time. Because that’s when you get to write. That’s when you get to explore. Q. But there are other ways to pay for that. For example, when my boys were little, before Chloe was born, we had five courses to teach. I would take one quarter without pay and take three courses across the year. So I would do one course each quarter, which was fine because we had enough money. I was lucky in that regard. But I didn’t get credit for those quarters because I wasn’t working. On one hand, I think that’s fair, but on the other hand, when I approach retirement, I won’t have credit for those. So there are issues there that can come into the equation. That’s right. It’s very difficult because...as we get further into the institutionalization of these things, problems arise. For example the problem where the man claims credit for childcare and doesn’t do it. You can put it some kinds of semi-safeguards against that by having the faculty member who’s doing it say to the dean or the chair of the department what they’re going to do. But the problem is that almost anything you put in to hold back the unscrupulous men also holds back the over scrupulous women. So it’s a very delicate balance. Issues like these heavily favor people who have money. So it’s terrifically difficult to work out something that’s fair. It’s not exactly as if you can just push the “fair” button and the fair thing happens. Q. As you mentioned, many women faculty are now married and have children. But many of them have a lot of resources that other working women, sometimes junior faculty, do not have and certainly many female staff and graduate students do not have these financial resources. But they also get pregnant and have children. We have graduate students with children, and we don’t make those provision for them. Yes, it’s really very difficult. Childcare is very expensive. We couldn’t get the president at Northwestern even at all interested in childcare. Here at Harvard, they have some but it’s very difficult to get into and it’s very expensive. I’ve known assistant professors who didn’t have tenure who got into the childcare system but didn’t do it because they felt they couldn’t afford it. I felt, “Oh my god, you don’t understand! You should be taking out loans [to pay for the childcare] if you’re not tenured.” But another thing that universities can do is network more on searches. Search committees can do a lot. We have at the Kennedy School a handbook saying that when a search committee has to make phone calls, asking about who’s on the market, they are required to call at least one woman and at least one person of color. For one thing, it forces them to find among their acquaintance someone who is female (laughter). So you can do things like that. You can also tell them to take Mahzarin Banaji’s Implicit Association Test. We’re all sexist. We’re all racist. To different degrees. We have to realize that. There’s so much that could be done institutionally. Yet even in 2013, we’re not doing it. Q. You talked about search committees. We have equity advisors at UC. Committees would come in with the three people they want to bring in for the position. If they have no woman or minority among the three, they have to justify to the equity advisor how they put together this group of people. Judy Singer here plays the same role. She’s supposed to play that role for every single tenure case or incoming search. Q. Why do you think Harvard is reluctant to do that at the more local level? California’s done it for years. I’m not even sure that they’re reluctant. What happened was that there was this one moment, toward the end of Larry Summers’s presidency, where we were able to make tremendous strides. We struck while the iron was hot and the door was opened. Then it closed. Even with Drew. Drew came in and she inherited this incredible recession, and it was very difficult for the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. I think the Government department has gone down from...I can’t remember what...let’s say 54 FTEs to 41. You’re trying to do the same job with the same number of students, but with many fewer faculty and everybody’s furious. There’s no hot breakfast for the students. Everybody’s upset. And that was just what happened in her first year. So I think there’s no sense of margin. In the 60s-- people forget -- the 60s were a time of enormous prosperity. Gold was lying on the streets and you could do anything. My plan was to get a PhD but if I couldn’t, I’d make sandals in Harvard Square. It’s not like you guys [speaking to the students in the room],you’re looking at careers, you’re worried that there are other people doing the same, and you’re competing. But back in the 1960s, we really weren’t competing that much. The idea that we couldn’t get some sort of job was unthinkable. You didn’t need much more than some sort of job. The rents weren’t as bad as they are now. I lived in a rent-controlled apartment and it was $80 a month for me and roommate together, so $40 each. Even counting inflation, that was very terrific. Q. So you think that when the economy is in good times, things get better for women? I do think so. I think that when the economy gets better, there will be a progressive resurgence. It’s not true that when things get worse, you get lots of progressive movements, because in bad times everybody’s holding onto what they’ve got. It’s high anxiety, high suspicion, and anybody who can be scapegoated is going to be scapegoated. I’m really surprised that the American polity has not been worse than it is. I don’t think it’s a good time for women. It’s fine in the sense that there is ongoing institutional change and ongoing generational change. That’s all good. But not in the sense of expecting moments in which the institution sits back and goes, “Well, let’s take a look at this issue of women. Let’s do this seriously and have a task force.” The reason I want you to do your book is because nobody’s going out and saying “Let’s see what the good programs are at all the good universities, and let’s have what Evelyn Hammonds used to call -- she was our first Senior Vice Provost for Faculty Development and Diversity -- a Race to the Top, an arms race where people at Harvard would notice they’ve got this or that at California and they would get embarrassed not to have as good a program.” Q. That isn’t happening now. Do you think that’s just the economy? Not just the economy, but the economy and all of the focusing of attention on other things that comes with that. Even on the left, attention’s being drawn more to larger inequalities in America, looking at economic inequalities. People were finally realizing that the rate of mobility in the US is not as high as in Europe. That’s the kind of thing that people are beginning to pay attention to now, and I think that that’s because of the economy. But we [women] will be ready when the door for us begins to open again. JC: As a follow-up to what you were saying before about how the search committee would have to have a woman and a person of color to call, some people say that policies like those lower the standards for the people we’re seeking out. Do you think that that’s true? No, I think it’s a matter of networks. There’s just been a wonderful article looking at citations within IR journals. The authors find that men cite men and women cite women. And since it’s mostly men in IR, this means that men get cited much more than women. Why is that important? Networks. It’s networks of people you know, people you’ve had lunch with, etc. So it’s a matter of calling someone who knows that network of good black scholars and can say, “What about so and so?” Because they [blacks] tend to not be in the friendship networks [of whites]. They might do very well and be writing good papers and so forth, but they wouldn’t be in the friendship networks of the people on the search committee. So the members of the committee just forget them. It’s not evil. It’s just that if you make an effort to call somebody, Kristen will think of me, I’ll think of Kristen. It’s not an accident that women come to my mind, because I know them. Same with men. So if you reach out consciously and broaden out consciously, it’s not a matter of lowering standards, it’s a matter of finding good people. It’s also true though, that the way we measure things here at Harvard is not good for minorities or women. One thing that Harvard has great difficulty with is that the standard for tenure is that you’re the best person that the university can get in that field. Which is a great standard in one way. But in another way, it very much disadvantages people who are at the intersection of one field or another. So for example, if you asked if I’m the top political theorist in the US, totally not! There are tons of people who would be considered better political theorists than me. Am I the best in women and politics? Absolutely not, there are loads of people better than me. But if you asked about the intersection of x and y, then I might well be the top person at that intersection. But as soon as you say the intersection of x and y, they’re going to say, “Aha, you named that intersection just to get Jenny Mansbridge.” Whereas at most other places, the criteria is, “Is this person good enough to get tenure at Princeton?” “Is this person good enough to get tenure at the University of Chicago?” And that doesn’t have this in-the-field feature, but Harvard does. Minorities and women are disproportionately likely to look for real problems and to be inspired by problems in the world. To solve real problems, you often have to bring in more than one discipline or be at the intersection of one discipline and another. So from the point of view of standards, for being good in this extremely narrow way, in x field -- let’s say Congress -- you’re not going to have as many women and minorities. Q. I want to disagree with you just a little bit on the citation. I was actually part of that panel. There was a symposium on the citations. It isn’t just a network phenomenon; they’ve done studies that show that if a woman is the first author on a piece, the piece is less likely to be cited than if a man is the first author. So I think there’s still some bias in citations. That’s true. Since we’re doing personal stuff, I’ll give you an example. Maybe just a week ago, I was at a seminar at a table twice as long as this, and the guy who was running the meeting -who is known at the Kennedy School for, not really being a sexist in a nasty way or as a sexual harasser, but just not getting that women are smart, etc. -- was sitting here [indicates the seat next to her]. I was sitting beside him, and another male colleague was sitting beside me. There were about forty people in the room, pretty much all men. There were only about four women out of 40 people. A very heavy imbalance that I noticed the moment I walked in the room. The man leading the discussion said, “I’d like to begin the meeting by asking if anyone has had anything interesting that happened to you in the last few weeks, something in your recent experience that would interest the group.” Then he looked right over me to the male colleague next to me, and said, “Do you have anything?” The male colleague responded. I thought maybe they must have a small group, a small sub-department, and maybe he’s just asking people from that small department. But then the man leading the discussion looked at the next person at the table and said, “Well, how about you?” This person had come over from the law school. At that point, I realized, no, he wasn’t just asking people from some small group at the Kennedy School. So I said, “I’ve got something that I think would be interesting to the group.” I told them about the Task Force I’d just created as president of the APSA, which was of course very interesting to the group. I didn’t get upset but I noticed it [shrugs]. Q. But this was last week, not thirty years ago. Right! Now this man is unusual. Thank god these people are aging out. There’s really a cohortreplacement effect to some degree. But at one level, it was just so funny. I wish there had been a camera there. It was literally as if I didn’t exist. He looked over me to the male colleague and then to the next male colleague. So when I saw the dean afterwards, I said, “I don’t know if you noticed that little interaction.” He said, “No, I didn’t, but I’m glad you brought it to my attention.” When you get older, you’re friends with the dean so you can say stuff like that. Q. That’s exactly what Theresa [Harvard student] was saying about being in math study groups. The male students will be sitting right next to her, and if they have a question, they’ll walk across the room and ask the other guy and not her. There’s a wonderful New Yorker cartoon where they had a man at the head of a big conference table and he says, “Thank you, Ms. Applebee. Now would anybody else here like to say what Ms. Applebee said?” so that we can record it. Q. What that cartoon notes is the extent to which being male provides legitimacy. That relates to a phenomenon I called gender devaluation in the Irvine study. For example, being chair of a department or being dean is considered a powerful situation, one that confers authority and influence and power, until a woman gets in there and then it’s reconceptualized in some subtle way into a service role. This relates to the gender schema we all have, in which women are supposed to take care of people. People have very different views of professional people; men are supposed to be very logical, aggressive, and ambitious and women are supposed to be very nurturing, collaborative, cooperative, and take care of people. It’s very hard when someone doesn’t fit into that model because they get pushed aside or people don’t know how to relate to them. But then if you fit into the male model as a woman, you get discriminated against. So how do you deal with those kinds of leadership skill differences? For example, you spoke with the dean after this incident. But did anything come of that? And what about the APSA, which is pretty political. But don’t forget, you and the rest of the women’s caucus got the APSA to have an encouragement or an admonition -- not a rule -- that there shouldn’t be more than two presidents in a row of one gender. I think that’s the reason why I’m president of the APSA. I think it’s because of what women did. There is no doubt in my mind. The wonderful thing is, whoever expected to benefit from all the stuff we did? Just like for any social movement, you do it because it’s right. The idea that there would ever come a day when I would actually benefit from the women’s movement...it’s kind of fun. It’s really neat. EH: How is it at the Kennedy School today, in terms of the numbers of female graduates and the faculty? The faculty is much harder. For the female graduate students, I think it’s about 48%. So it’s quite good. With regard to the faculty, it’s much much lower. Political science and economics are on the low side anyway, compared to psychology or sociology, economics being worse than political science. And the Kennedy School is half economists and some political scientists. The number of women we have is actually right between the numbers the economics department has and the number the political science department has in FAS, so it’s relatively predictable. There are certain things in the Harvard structure that I mentioned that make it harder for a woman or a member of a minority -- because of what we study -- to get tenure here. Then there’s always these implicit associations and the citations, etc...The thing about citations is that they’re held to be absolutely objective. But they’re not. They’re connected to these networks and to discrimination. So to answer your question, at the JFK School we’re no worse than the comparative parts of Harvard; namely, we’re better than economics, and a little bit worse than political science. Q. Is it about 20%? The last appointments, I think, may have been about 50% women. David Ellwood, the dean, and before him, Joe Nye, are both very committed to this. We’ve also got the Senior Vice Provost for Faculty Development and Diversity who is kind of on your case if this thing gets too unbalanced. She’s going to be asking you why. Q. So how many women are tenured in the Kennedy School now? You were the third one. Have they tenured any women since then? Since me? Oh yes. I can probably count if I went through it, but yeah. I would say that at least twenty percent of the tenured faculty are women [23 percent in fact]. I would give you those numbers if I knew...I’ve got them at home. That’s why I didn’t go into history, I’m not too great at numbers. (laughter) Q. I think it sounds as if women have a more difficult time at more traditional schools. Compared to what? Q. For example, California is much farther advanced than Harvard in terms of all kinds of things that you don’t have. For example, you don’t have training on sexual harassment at Harvard at all. It’s absolutely mandatory in California. You have to redo it every three years and it takes a long time to do, about two hours. If you don’t do it, you don’t get paid. Well, it’s not just traditional schools. It’s literally, again, just Harvard. Here’s another structural/cultural fact. We had this wonderful women’s association at Northwestern, and by the time we left, Northwestern was hiring one-third women. That was fifteen years ago. We in the Association of Women Faculty worked with the University because Northwestern, when I got there, wasn’t a first ranked university but sort of lower, second-rank. It was definitely trying. The Association of Women Faculty went to the administration and said, “If you do the following things, you’ll go up in the ranks and at the same time, there will be more women and minorities.” Some of the things included departments just reading the work of the people they were thinking to hire. If you just take the recommendations of graduate students, the ones who get the best recommendations will go to the top colleges and the ones who get the second tier recommendations will go to the second tier schools, and the third will go to the third, and it’s a completely self-replicating system. There’s no way to break out of it if you’re in the fourth or the fifth tier. But if you actually empower your faculty and tell them you want them to read the work and maybe take a risk...Go for work that you think is exciting, even if the person doesn’t have a good recommendation. Then A: You’ll move up the ranks. B:. You’ll get more women. And it did work! Northwestern did go up the ranks and it did get more women. We also said, exploit the fact that you’re in Chicago. You can do spousal hires. They appointed one full-time person working on getting jobs for spouses in the Chicago area. There are other universities that are more out there in the country, but we were in Chicago, where the black bourgeoisie is big. And we can get people who have families because we can find jobs for spouses.. Exploit the fact that we have performing arts. We could get wonderful black faculty that way. Just think about it. Try it and see if both things will happen. And when they did try, both things did happen. So I came to Harvard totally ready to go with all these wonderful successes at Northwestern and just ran into one closed door after another. I’m not the kind of person who continues to hit her head against a locked door so I gave up after a year. What I realized was that Harvard, over the years, has pulled away from Princeton and Yale. When I went to school, it was Harvard, Yale, and Princeton all sort of equal and mushed into the Ivy League. Harvard has pulled up compared to Yale and Princeton and they haven’t a clue why they have. There’s no explanation. If that’s the case, you don’t want to change anything in the formula. Northwestern wanted to change. We could ride the wave of change and we could help it happen. Harvard doesn’t want to change because the only place it has to go is down. So it’s scared to death of doing anything that might screw up this formula. Q. But if you rewrote the narrative for them, Harvard is number one, Harvard should be taking the lead, Harvard should be showing others how to increase minorities and female faculty, and so on. Why hasn’t that been accepted here? I do put a lot of the blame on the recession. We did have that task force during Larry Summers’s presidency. We really got that going, Evelyn got that going. The whole positive arms race thing. At periodical intervals, every year, a council was going to get together and compare the top twenty universities and university systems and sees who is doing what and getting people to compete. That just didn’t happen. That’s why I want you to do this book because I want the book to play that role of comparing universities’ innovations to see which ones work. Q. You certainly can tell people what the options are but you can’t make them follow those options if they don’t want to do so. I’ve talked to people at different places, including Harvard. When I suggested specific things that have been done elsewhere with success, and asked if these same policies had been tried at Harvard, the response was, “Well, that wouldn’t fly at Harvard.” Do you think that has something to do with tradition, something newer, public universities would not have? Beyond that, there’s a tendency in many schools – including Harvard, when you think of recent problems with sexual harassment – to just bounce upstairs people who sexually harass, to make them administrators instead of teachers. There’s a tendency that universities have, being guilds, of protecting their own, a little bit like the Catholic Church. But I do feel that in the United States, we are pretty low with regard to any of this. Women’s groups are pushing, our group in political science, and me and you, we’re pushing. But people aren’t grabbing on. We just have to wait. I came to Harvard and there was nothing that could be done so I said, “Ok, I’m going to go do political theory.” Then when Larry Summers put his foot in his mouth, bam! I was on leave that year, actually at the Radcliffe Institute, and you know how precious it is to have a year’s leave. Nevertheless I took a bunch of that year from my own work and gave that time to the task force because I thought this is our moment. Q. But part of this then, is political leadership. You talk about being APSA president. I know how you got there because I was involved in it. I learned from past experience that the CSWP had to put more than one woman’s name on the list of women they want as president, otherwise the powers that be can find something wrong with just one name. But if you add more than one name, then you expand the choices, and it’s more likely to get a good woman into office. So your name deliberately got put on the list by other women. Then the CSWP went around to the other minority status groups and they endorsed it. So your name went in along with some other names and with endorsements of other status committees. But that wouldn’t have happened if somebody hadn’t made it happen. So sometimes, it is a question of political leadership and opportunity and one person can make a big difference. I completely agree. But I also think, as with Machiavelli, that you have to wait until Fortuna’s with you. Because otherwise, you can burn out. You can just get really, really tired of shaking people’s shoulders and saying, “Don’t you see?” Sometimes, it’s just a matter of just one other person. It’s nice that you’re here this year. It’s really really nice. Maybe you just get one other woman joining the department and joining the school who’s an activist and understands what it is to work for a cause. Then with the two of you, you can begin to create critical mass; even if it’s a small group, it’s still a critical mass. I think in the APSA, the women’s caucus is a wonderful thing. It serves as that critical mass. Q. And we worked with the other status committees. (to students) Yeah. APSA has got these status committees, which are Asian, Latino, AfricanAmerican, and LGBT. These are groups that the organization gives money to, to help them organize. Which is really critical. For example, you read the Daily Worker back from the 1930s, and you have all these workers writing. It’s a magazine that not run by workers for workers, but by elites for workers. But still there’s a lot of worker participation, and it’s because Russia’s funding the damn thing. Just a little bit of money can make a huge difference. Q. Is there any advice you have for young people, such as these girls here with us tonight? Go for it! VP: A recent op-ed in the New York Times argued that women have hit a wall in the women’s movement. Personally, I feel a lot of people – both men and women -- believe there was second wave feminism and now women work and are in all sorts of these top positions, so it’s fine. They say there isn’t as overt discrimination, so there isn’t really anything left to do. Do you think that’s a correct view? And what’s your advice for what should be done to combat this idea? If you just ask somebody two questions. First, “Who do you think in general has primary responsibility in child-rearing, men or women?” They’re not going to say men. Then the second question is, “How do you think that plays itself out, with regards to women’s successes across the board?” There’s no way that they don’t see the point then. My dean, a very good guy, was talking about the Women in Public Policy Program at the Kennedy School and how that might evolve. He dropped some parenthetical phrase about how maybe it might not continue. And I said, “David, do you think that two generations from now, there is not going to be a reason for a Women in Public Policy program at the Kennedy School?” All he had to do was think about it, and he said, “No, you’re right.” Q. But you had to be there to say that. One person can make a difference. Another thing you point out, if you’ve done the Implicit Associations Test, is to just say to somebody, “Do the Implicit Association Test.” I have an Israeli friend who has a black daughterin-law. They get into a big fight about whether my friend, Sarah, was racist. She was claiming she was not. I told her to take the test. She did, and then she went back to her daughter-in-law and apologized. What we are finding out now is that there are lots and lots of subtle priming. The lay public is becoming aware of the effects of priming. Certainly the academic public is becoming aware that you can prime all sorts of gender-stereotypes -- and the priming’s all over the place. Just turn on the television, and you’re flooded with gender primes. And those primes have these implicit associations. We can tell people now, “This is a long and subtle battle.” And in it, we need people who are willing to say something to the dean. We need Jenny to find Kristen and Kristen to find Jenny and us to work on putting this knowledge in a book. We need people who are going to say yes to be interviewed, we need to work together and find each other. That’s going to have to happen, way into the future. If people don’t see it right now, you can say, “You’ll see it eventually.” People will see it mostly when they go into the workforce. Academia is a relatively meritocratic place. [looking at the students] All of you have the experience of going through kindergarten, first grade, second grade, third grade, etc. You take your tests, you take your exams. You’re graded like the boys and if you do well on the test, you get an A. If you don’t do so well, you get a B+. It’s the same test as the boys took. Compared to the world after academia, it’s pretty meritocratic. I’m not saying that it’s fully meritocratic, but compared to the outside world, it is. [Speaking to the students] So don’t knock your head against the wall like me; they’ll come around. After they’ve had their third child, they’ll suddenly notice, “Oh my god, this isn’t quite what I had in mind.” But you can’t predict things. Nobody predicted the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, or the environmental movement. These things have extraordinary, weird lives of their own. It is like Machiavelli says; you have to be ready to jump on the wave when it comes. Tell your friends a few things but don’t knock yourself out if they don’t want to hear. They’ll hear it eventually, but it might not be right now. And find some friends who do hear what you have to say, and that’ll be fun too. ………………………………………………END HERE……………………………………. [interview ending; footage change. Discussion of final clubs] ...They got rid of the old house system. Cracking down on the drinking age and getting rid of the character of the houses was intended to improve Harvard. I wouldn’t say that the houses are now characterless, but they don’t have character the way they used to and they’re not communities like the way they used to be. So if you’re looking for a community, you have to fall back on sororities. My first reaction to the introduction of sororities on campus was, “Oh my god, the mighty have fallen.” But then I thought, well geez, if there are male fraternities, I suppose there should be female sororities. But it’s just terrible. It’s really different from when I was here as a graduate student. Or even when I was an undergraduate. If someone joined a final club back then, you thought, “Oh, what kind of a person are they?” Really, it was just sort of awful. Nobody self-respecting would go out with somebody like that. The final clubs were considered something for preppy losers. Preppies huddling together for warmth when they couldn’t find anything else to do. It was really over-the-top binge drinking and it was like, why does somebody need to do that? Get a life! Now, it’s not like that. A sea change has taken place in my lifetime. It’s disgusting. The world has changed, but there were also these specific changes that Harvard did that have made it worse here. For example, Princeton has just gotten better in these dimensions. Q. But they just got rid of the fraternities. They just became social units. Why has Harvard not been able to do anything about the final clubs? The explanation I’ve gotten is that the clubs who own the houses. The houses are not Harvard-owned. They’re off-campus and the alums have so much money so Harvard does not want to challenge or change them. Both of those things are true. But there’s been this change. The meaning of the houses has changed at Harvard. I don’t know about you guys (pointing to students)... I don’t know what you do for your identity. Is it your house? EH: It’s nice to see familiar people in the dining hall. Right, but it’s a physical place. People used to say, “I’m in Adams House,” and that meant that you were kind of literary, etc. They had their own theater group, for example. There were these real characters to a house. As a freshman, you would decide what you wanted for your community. If not for quite an identity at least for a community. You decided where it was you wanted to go. Then you’d buy into that, and there was a lot of community around that. I think that that kind of thing is provided for most people; for most people, it’s provided by things like the Crimson or some voluntary thing that they do, but for a number of people, it’s provided by these horrible clubs. VP: I think I do identify with my house. I’m in Mather. The character of the houses is much less and much different because there are so many different people. But one of the things I see with the clubs is that Harvard is a little limited in what it can do because decades ago, it said, “Well, if you’re going to discriminate, then we’re not going to recognize you,” and it kind of cut off certain groups. So if Harvard took these stances against organizations that are discriminatory and against people of different races and different identities segregating themselves and forced equality onto them, how can Harvard strike the balance between standing for these values and letting them having less control over these negative side effects? I don’t know. I don’t have an institutional solution for Harvard. I can see how it happened. I can see the two strong causes of preventing drinking and preventing marginalized groups getting together and self-segregating. I don’t that either will change soon. . I don’t see Harvard getting more lax about drinking and I don’t think it’s going to change those other rules either. I don’t know what the answer is. There will be ways of building up the houses. But you know more about that because you’re in them. So ask your friends. One way of doing it might be having subhouses within the houses. I don’t know. But what we need is real communities that are going to make people feel like they’re going to go down to the dining hall and see 20 of their friends. They’re going to be talking about something that the house was doing or what happened yesterday in the house or common enterprises that they belong to and they’re trying to make happen because it’s a thing that the house is doing. Things that you pull yourself into a community.