No crowd out – donations are primarily for friends and relatives

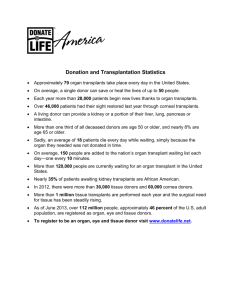

advertisement