talitha dehaene 1426745

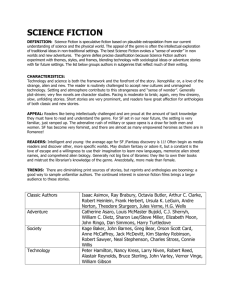

advertisement