draft shell

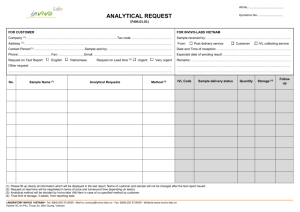

advertisement

MDAW 2012 Kritik draft shell [don’t use in debates until the file comes out] Lab Name 1NC Long Shell 1 A. Their call for economic engagement is grounded in the desire to re-center the U.S. in the world picture. Insisting that the U.S. stays a part of Latin America is a self-justifying epistemology that christens it with a mission to tame the wilderness Spanos 2k (William, English @ Binghamton, America’s Shadow pp.143-4) In the wake of the Cold War, and especially the defeat of Saddam Hussein's army — and the consequent representation of the shattered American consensus occasioned by the Vietnam War as a recovery of a collective mental illness — there came in rapid and virtually unchallenged succession a floodtide of "reforms," reactionary in essence, intended to annul the multiply situated progressive legacy of the protest movement(s) of the Vietnam decade by overt abrogation or accom- modation. Undertaken in the name of the "promise" of "America," these reforms were intended to reestablish the ontological, cultural, and political authority of the enlightened, American "vital center" and its circumference and thus to recontain the dark force of the insurgent differential constituencies that had emerged at the margins in the wake of the disclosures of the Vietnam War. At the domestic site, these included the coalescence of capital (the Republican Party) and the religious and political Right into a powerful dominant neoconservative culture (a new "Holy Alliance," as it were) committed to an indissolubly linked militantly racist, antifeminist, antigay, and anti-working-class agenda; the dominant liberal humanist culture's massive indictment of deconstructive and destructive theory as complicitous with fascist totalitarianism; the nationwide legislative assault on the post-Vietnam public university by way of programs of economic retrenchment affiliated with the representation of its multicultural initiative as a political correct- ness of the Left; the increasing subsumption of the various agencies of cultural production and dissemination (most significantly, the electronic information highways) under fewer and fewer parent, mostly American, corporations; the dismantling of the welfare program; and, symptomatically, the rehabilitation of the criminal president, Richard Nixon. At the international site, this "reformist" initiative has manifested itself as the rehabilitation of the American errand in the world, a rehabilitation exemplified by the United States's virtually uncontested moral/military interventions in Panama, Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia, the Middle East, and Kosovo; its interference in the political processes of Russia by way of providing massive economic support for Boris Yeltsin's democratic/capitalist agenda against the communist opposition; its unilateral assumption of the lead in demanding economic/political reforms in Southeast Asian countries following the collapse of their economies in 1998; its internationalization of the "free market"; and, not least, its globalization of the instrumentalistversion of the English language. What needs to be foregrounded is that these global post-Cold War "reformist" initiatives are not discontinuous practices, a matter of historical accident. Largely enabled by the "forgetting" of Vietnam — and of the repression or accommodation or self-immolation of the emer gent decentered modes of thinking the Vietnam War precipitated — they are, rather, indissolubly, however unevenly, related. Indeed, they are the multisituated practical consequences of the planetary triumph (the "end") of the logical economy of the imperial ontological discourse that has its origins in the founding of the idea of the Occident and its fulfilled end in the banal instrumental/technological reasoning in the discourse of "America." In thus totally colonizing thinking, that is, this imperial "Americanism" has come to determine the comportment toward being of human beings, in all their individual and collecti ve differences, at large — even of those postcolonials who would resist its imperial order. This state of thinking, which has come to be called the New World Order (though to render its rise to ascendancy visible requires reconstellating the Vietnam War into this history), subsumes the representative, but by no means complete, list of post-Cold War practices to which I have referred above. And it is synecdochically represented by the massive mediatization of the amnesiac end-of-history discourse and the affiliated polyvalent rhetoric of the Pax Americana. Page 1 of 5 MDAW 2012 Kritik draft shell [don’t use in debates until the file comes out] Lab Name 1NC Long Shell 2 B. State-oriented foreign policy assumes the world map created by colonialism as universal, silencing non-State histories and sites of agency Michael Shapiro, professor of political science at university of HI, 1997 “Violent Cartographies” p.195-7 Apart from its immediate legitimation for colonization. Mill’s interpretive complicity with the European “advance” exemplifies more generally the interrelationship of spatial practices and ethical sensibility. To be an object of moral solicitude, one must occupy space and have an identity that commands recognition of that occupation. Mill’s disparagement of American peoples is simply the modern, state-oriented cartography of violence. It is a moral complacency based on the universalization of a particular spatial imaginary and mode of dwelling within it, a failure to allow one’s particularities the instability and contingency that an ethical regard would suggest they deserve when confronted by alternatives. To disclose the structure of this spatial complacency and ethical insensitivity, Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari have represented the confrontation between the emerging state system and various tribal peoples with a geometric metaphor. The coming of the state, they suggest, created a disturbance in a system of “itinerant territoriality” While the normative geometry of these itinerantly oriented societies takes the form of a set of nonconcentric segments, a heterogeneous set of lineage based power centers integrated through structures of communication, the state is concentric in structure, an immobilized pattern of relations controlled from a single center. The state-oriented geometry produces a univocal code, a sovereignty model of the human subject that overcomes all segmental affiliations. For this reason, those, like Mill, schooled in the geometry of the state cannot discern a significant social and political normativity in segmentally organized groups. They see no collective coherence in peoples with a set of polyovcal codes based on lineage. In short, having changed the existing geometry, linear reason of stat dominates, privileging what is sedentary and disparaging and arresting what moves or flows across boundaries. It makes labor sedentary and counteracts vagabondage, and it gives the nomad no space for legitimate existence in various senses of the world space. This lack of legitimacy continues to be reflected in the inattention to spatial practices and marginalized identities in contemporary political and ethical discourses. Specifically, among what is silenced within state-oriented societies are nomadic stories, the narratives though which non-state peoples have maintained their identities and spatial coherence . In the context of what Deleuze and Guattari call the sate geometry, they are not able to perform their identities, to be part of modern conversations . Such cartographic and, by implication, ethnographic violence forecloses conversation. This violence of state cartography is elaborately described and powerfully conceptualized in Paul Carter’s account of the European encounter with Australian Aboriginal peoples . The European state system’s model of space involved boundaries and frontiers, and its advance during its colonizing period pushed frontiers outward. During the “stating” of Australia, when the European spatial imaginary was imposed, those on the other side of the frontier, the Aborigines, were given no place in a conversation about boundaries. Carter suggests what amounts to a Levinasian ethical frame for treating boundaries. The boundary could be seen as “a corridor of legitimate communication, a place of dialogue, where differences could be negotiated.” Indeed, by regarding a boundary as “the place of communicated difference” instead of proprietary appropriation (the European model), the Europeans would have summoned a familiar practice from the Aborigines. For Aborigines, boundaries are “debatable places,” which they regarded as zones for intertribal communication. As we know, however, Australia was ultimately “settled,” and the boundaries served not to acknowledge a cultural encounter but to establish the presence of the Europeans, practically and symbolically. This violence, which substituted for conversation, is already institutionalized in the form of what is represented as “Australia” just as other names and boundaries on the dominant geopolitical world map are rigidified and thus removed from the possibility of encounter . To the extend that community, society, and nation fail to reflect the otherness within, we have a cartographic unconscious, an ethics of ethics that establishes a set of exclusionary practices that are represented in the seemingly innocent designations of people and place. The various discourses springing from this unconscious are legion; for example, as I noted earlier, “the ethics of international affairs” reaffirms the violences, the non-encounters and non-conversations, that the state system perpetuates. It is time to unread the old map and begin the process of writing another one, a process without limit. Page 2 of 5 MDAW 2012 Kritik draft shell [don’t use in debates until the file comes out] Lab Name Long Shell 3 C. The U.S.-centric colonialist worldview is a metaphysics that conflates rationality with coloniality. It can only see the cultural agency of others as obstinate material to be annihilated. The genocidal violence of the Vietnam war is an exemplar for what happens this goes unchecked. Spanos 8 (William V, Professor of English at Binghamton University, American Exceptionalism in the Age of Globalization: The Specter of Vietnam, p. ix-x) In this book I contend that the consequence of America's intervention and conduct of the war in Vietnam was the self-destruction of the ontological, cultural, and political foundations on which America had perennially justified its "benign" self-image and global practice from the time of the Puritan "errand in the wilderness." In the aftermath of the defeat of the American Goliath by a small insurgent army, the "specter- of Vietnam—by which I mean, among other things, the violence, bordering on genocide, America perpetrated against an -Other" that refused to accommodate itself to its mission in the wilderness of Vietnam—came to haunt America as a contradiction that menaced the legitimacy of its perennial selfrepresentation as the exceptionalist and -redeemer nation.- In the aftermath of the Vietnam War, the dominant culture in America (including the government, the media. Hollywood. and even educational institutions) mounted a massive campaign to "forget Vietnam." This relentless recuperative momentum to lay the ghost of that particular war culminated in the metamorphosis of an earlier general will to "heal the wound" inflicted on the American national psyche, into the "Vietnam syndrome"; that is, it transformed a healthy debate over the idea of America into a rational neurosis. This monumentalist initiative was aided by a series of historical events between 1989 and 1991 that deflected the American people's attention away from the divisive memory of the Vietnam War and were represented by the dominant culture as manifestations of the global triumph of "America's: Tiananmen Square, the implosion of the Soviet Union, and the first Gulf War. This “forgetting” of the actual history of the Vietnam War, represented in this book by Graham Greene's The Quiet American, Philip Caputo's A Rumor of War, and Tim O'Brien's Going After Cacciato hand many other novels, memoirs, and films to which I refer parenthetically, contributed to the rise of neoconservatism and the religious right to power in the United States. And it provided the context for the renewal of America's exceptionalist errand in the global wilderness, now understood, as the conservative think tank the Project (or the New American Century put it long before the invasion of Afghanistan and Iraq, as the preserving and perpetuation of the Pax Americana. Whatever vestigial memory of the Vietnam War remained after this turn seemed to be decisively interred with Al Qaeda's attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001. Completely immune to dissent, the confident American government, under President George W. Bush and his neoconservative intellectual deputies— and with the virtually total support of the America media—resumed its errand in the global wilderness that had been interrupted by the specter of Vietnam. Armed with a resurgence of self-righteous indignation and exceptionalist pride, the American government, indifferent to the reservations of the "Old World," unilaterally invaded Afghanistan and, then, after falsifying intelligence reports about Saddam Hussein's nuclear capability, Iraq, with the intention, so reminiscent of its (failed) attempts in Vietnam, of imposing American-style democracy on these alien cultures. The early representation by the media of the immediately successful "shock and awe" acts of arrogant violence in the name of "civilization" was euphoric. They were, it was said, compelling evidence not only of the recuperation of American consensus, but also of the rejuvenation of America's national identity. But as immediate "victory" turned into an occupation of a world unwilling to be occupied, and the American peace into an insurgency that now verges on becoming a civil war, the specter of Vietnam, like the Hydra in the story of Hercules, began to reassert itself: the unidentifiability or invisibility of the enemy, their refusal to be answerable to the American narrative, quagmire, military victories that accomplished nothing, search and destroy missions, body counts, the alienation of allies, moral irresolution, and so on. It is the memory of this "Vietnam"—this specter that refuses to be accommodated to the imperial exceptionalist discourse of post-Vietnam America—that my book is intended to bring back to presence. By retrieving a number of representative works that bore acute witness, even against themselves, to the singularity of a war America waged against a people seeking liberation from colonial rule and by reconstellating them into the post-9111 occasion, such a project can contribute a new dimension not only to that shameful decade of American history, but also, and more important, to our understanding of the deeply backgrounded origins of America's "war on terror" in the aftermath of the Al Qaeda attacks. Indeed, it is my ultimate purpose in this book to provide directives for resisting an American momentum that threatens to destabilize the entire planet, if not to annihilate the human species itself, and also for rethinking the very idea of America. Page 3 of 5 MDAW 2012 Kritik draft shell [don’t use in debates until the file comes out] Lab Name Long shell 4/5 D. The alternative is to decolonize world picture. Disobedience against the AFF’s colonial epistemology Mignolo ‘11(Walter, Literature @ Duke, “Epistemic Disobedience and the Decolonial Option: A Manifesto” in Transmodernity: A Journal of Peripheral Cultural Production in the Luso-Hispanic World, pp. 45-6) But the basic formulation of decolonial delinking (e.g., desprendimiento) was advanced by Aníbal Quijano in his groundbreaking article “Colonialidad y modernidad/racionalidad” (1991) [Coloniality and modernity/rationality]. The argument was that, on the one hand, an analytic of the limits of Eurocentrism (as a hegemonic structure of knowledge and beliefs) is needed. But that analytic was considered necessary rather than sufficient. It was necessary, Quijano asserted, “desprenderse de las vinculaciones de la racionalidad-modernidad con la colonialidad, en primer término, y en definitiva con todo poder no constituido en la decisión libre de gentes libres” [“It is necessary to extricate oneself from the linkages between rationality/modernity and coloniality, first of all, and definitely from all power which is not 4 constituted by free decisions made by free people”]. “Desprenderse” means epistemic de-linking or, in other words, epistemic disobedience. Epistemic disobedience leads us to decolonial options as a set of projects that have in common the effects experienced by all the inhabitants of the globe that were at the receiving end of global designs to colonize the economy (appropriation of land and natural resources), authority (management by the Monarch, the State, or the Church), and police and military enforcement (coloniality of power), to colonize knowledges (languages, categories of thoughts, belief systems, etc.) and beings (subjectivity). “Delinking” is then necessary because there is no way out of the coloniality of power from within Western (Greek and Latin) categories of thought. Consequently, de-linking implies epistemic disobedience rather than the constant search for “newness” (e.g., as if Michel Foucault’s concept of racism and power were “better” or more “appropriate” because they are “newer”—that is, post-modern—within the chronological history or archaeology of European ideas). Epistemic disobedience takes us to a different place, to a different “beginning” (not in Greece, but in the responses to the “conquest and colonization” of America and the massive trade of enslaved Africans), to spatial sites of struggles and building rather than to a new temporality within the same space (from Greece, to Rome, to Paris, to London, to Washington DC). I will explore the opening up of these spaces—the spatial paradigmatic breaks of epistemic disobedience—in Waman Puma de Ayala and Ottabah Cugoano. The basic argument (almost a syllogism) that I will develop here is the following: if coloniality is constitutive of modernity since the salvationist rhetoric of modernity presupposes the oppressive and condemnatory logic of coloniality (from there come the damnés of Fanon), then this oppressive logic produces an energy of discontent, of distrust, of release within those who react against imperial violence. This energy is translated into decolonial projects that, as a last resort, are also constitutive of modernity. Modernity is a three-headed hydra, even though it only reveals one head: the rhetoric of salvation and progress. Coloniality, one of whose facets is poverty and the propagation of AIDS in Africa, does not appear in the rhetoric of modernity as its necessary counterpart, but rather as something that emanates from it. For example, the Millennium Plan of the United Nations headed by Kofi Anan, and the Earth Institute at Columbia University headed by Jeffrey Sachs, work in collaboration to end poverty (as the title of Sach’s book announces). But, while they question the unfortunate consequences of modernity, never for a moment is the ideology of modernity or the black pits that hide its rhetoric ever questioned: the consequences of the very nature of the capitalist economy—by which such ideology is supported—in its various facets since the mercantilism of the sixteenth century, free trade of the following centuries, the Industrial Revolution of the nineteenth century, and the technological revolution of the twentieth century. On the other hand, despite all the debate in the media about the war against terrorism, on one side, and all types of uprisings, of protests and social movements, it is never suggested that the logic of coloniality that hides beneath the rhetoric of modernity necessarily generates the irreducible energy of humiliated, vilified, forgotten, or marginalized human beings. Decoloniality is therefore the energy that does not allow the operation of the logic of coloniality nor believes the fairy tales of the rhetoric of modernity. Therefore, decoloniality has a varied range of manifestations—some undesirable, such as those that Washington today describes as “terrorists”—and decolonial thinking is, then, thinking that de-links and opens (de-linking and opening in the title come from here) to the possibilities hidden (colonized and discredited, such as the traditional, barbarian, primitive, mystic, etc.) by the modern rationality that is mounted and enclosed by categories of Greek, Latin, and the six modern imperial European languages. Page 4 of 5 MDAW 2012 Kritik draft shell [don’t use in debates until the file comes out] Lab Name Long Shell 5/5 E. Predictive approaches to policy require a normalization of expectations where each link is a billiard ball on a uniform surface. Prefer epistemological critique to their impact claims. Deloria 6 (Vine, World We Used to Live in: Remembering the Powers of Medicine Men, p.194) Our expectations in life are that events will occur in a cause-and-effect universe in which it is relatively simple to trace the beginnings and end of any natural phenomenon. When we experience an event or feeling out of the ordinary, we tend to dismiss it as unreal, a fantasy that somehow broke into our consciousness. We cannot explain what we have experienced because we have only this narrow, materialistic framework in which to evaluate what has happened. In a practical sense, the Newtonian billiard balls that clang together creating events and guaranteeing uniformity are sufficient for us. But what if we learned to have other expectations? Suppose we were of such a nature that we could discern the life force in everything and were thus assured that as we made our way through life, unusual things could happen. What if these events gave testimony that the physical world we know was but a manifestation of a larger cosmos that was beyond our powers to discern and was also part of our lives. We would then begin to attribute the cause of some unusual events as the intervention or intersection of unseen yet powerful forces that played a role in our experience, even if we could not see them. In theory, but not in daily practice, we do live in such a world. Page 5 of 5

![vietnam[1].](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005329784_1-42b2e9fc4f7c73463c31fd4de82c4fa3-300x300.png)