Potential research questions

advertisement

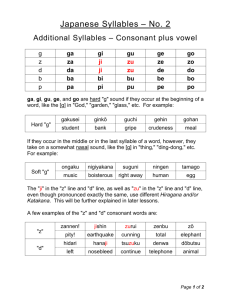

Daniel Guerrero LING 566 Potential research questions: These first two are more related to education than linguistics specifically, so I’m just counting them as one question: 1. This first question was prompted by a paper I read while writing an essay on second language acquisition, where the author claimed that before puberty, it’s more important for children to be properly educated in their first language than to emphasize a second, as their verbal abilities are still developing. “Before puberty, it does not matter when one begins exposure to (or instruction in) a second language, as long as cognitive development in the first language continues up through age 12 (the age by which first language acquisition is largely completed).” This didn’t have a specific citation for this claim, and I couldn’t find any particular studies that supported it, even though this potentially has significant consequences, especially in a city like Los Angeles where there are many children below the age of 12 who are only receiving education in English and not their L1. For example, my brother-in-law was raised speaking Lao, but never learned to read or write it; he learned to read and write only in English. Could this have negatively impacted his ability to read and write in general, and made his reading and writing abilities in English lower as well? My actual research question would be: Does receiving language education in one’s L1 before puberty improve learning outcomes in an academic L2 for bilingual students? The Paper: Collier, Virginia P. “How Long? A Synthesis of Research on Academic Achievement in a Second Language.” TESOL Quarterly, 23.3 (September 1989): pp. 509-531. JSTOR. 2 Dec. 2014. 2. The second is just something that I’ve observed working with bilingual children as a math tutormany children have trouble understanding problems that require “translation,” for example, “The sum of a number and four is the difference of seven and twice that number. What is the number?” In that problem you must take each word and turn it into parts of a mathematical equation. “Sum of a number and four” becomes “x + 4,” “is” becomes “=,” and “the difference of seven and twice that number,” becomes “7 – 2x,” leaving you with “x + 4 = 7 – 2x” which you can then solve. At middle school age, children really vary in their ability to understand concepts like that. But I’ve had bilingual students (students who were educated in both languages) who were very good at it, and at a young age, leading me to suspect that there could be a connection between these two “translation” abilities. I know that there has been some study between music education and mathematical abilities, so perhaps there is room for study of this as well. My research question for this would be: Does bilingual education improve [these particular] mathematical skills? 3. I’ve noticed something that American English Speakers do when pronouncing a particular type of foreign name- if it has a /d/ or /t/ sound in the middle, and stress on the first syllable, they will instead put the stress on the second syllable. (I don’t remember how to transcribe stress, but as an example, the name “Aar-ti” is pronounced by Americans as “Aar-ti.”) I suspect this is to avoid using an alveolar tap (/ɾ/), which they sense is an “incorrect” way to pronounce a name with a “t” in the middle. So for this my research question would be: How do American English speakers reconcile or transfer the alveolar tap with words from other languages? 4. This question may have already been researched, but I’ve noticed (and heard from others) that consonant clusters provide an extra puzzle to Japanese speakers. Japanese only has two acceptable consonant clusters that I am aware of, /st/, as in /steki/, which means “lovely,” and /sk/, as in /ski/, which means “liked.” Some consonant clusters are difficult to impossible for a Japanese speaker to reconcile, for example, “drive” can only be pronounced /doraiv/, and truck as /torak/ or /toraku/. I’ve noticed that consonant clusters also seem to make it more difficult for Japanese speakers to maintain a difference between /ɹ/ and /l/. (My Japanese professor very consistently used /desklaib/ for “describe,” even though she was very good at pronouncing l and r in other words). My research question for this would be: How do consonant clusters affect Japanese speakers’ abilities to produce /l/ and /ɹ/ sounds, and is it different than in other languages (perhaps a language that has more consonant clusters than Japanese, but still no l/r difference)?