Overview: Drawing from the Deck of Genes

advertisement

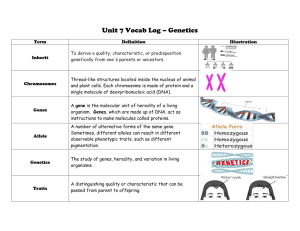

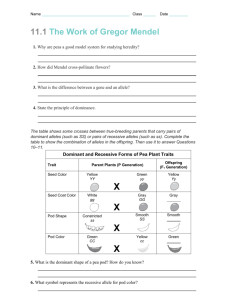

Chapter 14: Mendel and the Gene Idea Overview: Drawing from the Deck of Genes Mendel had a theory that heredity came from genes and that’s what this chapter is about 14.1 Mendel used the scientific approach to identify two laws of inheritance Mendel’s Experimental, Quantitative Approach Two of Mendel’s main influences were physicist Christian Doppler and a botanist named Franzy Unger Mendel bred garden peas in the abbey garden to study inheritance o Because they’re available in many varieties Character—a heritable feature that varies among individuals o Ex: a flower’s color o Trait—each variant for a character Ex: purple and white color are variants for the character of color of a flower Mendel also used peas because they have a short generation time, large number of offspring from each mating, and he could control the mating between the plants true breeding—a plant with purple flowers is true breeding of the seeds produced by selfpollination in successive generations all give rise to plants that also have purple flowers Mendel cross-pollinated two contrasting, true-breeding pea varieties o Ex: purple flowered plants and white flowered plants o Hybridization—the mating, or crossing, of two true-breeding varieties P generation—the true breeding parents (parental generation) F₁ generation—the hybrid offspring of the P Generation F₂ generation—when the F₁ generation self pollinates, it’s produced o Mendel followed traits for these three generations Through his tests, Mendel saw two fundamental principles of heredity: the law of segregation and the law of independent assortment o He put them to the test again and again The Law of Segregation Results of first experiment: o P generation: purple and white flowers o F₁ generation: all purple flowers o F₂ generation: 705 purple flowered plants, 224 white flowered plants—3 to 1 ratio There was confusion at first because the blending between white and purple flowers didn’t make pale purple flowers, but it didn’t make all purple or all white, so both of the genes had to be there He named the purple flower color the dominant trait and the white flower color the recessive trait Mendel’s Model Mendel developed a model to explain the 3:1 inheritance pattern: o 1. Alternative versions of genes account for variations in inherited characters Ex: gene for flower color in pea plants exists in two versions: one for purple and other for white Alleles—the alternative versions of a gene We see this example today in how each gene is a sequence of nucleotides at a specific place or locus along a certain chromosome, but the DNA at that locus can vary slightly in its nucleotide sequence o 2. For each character, an organism inherits two alleles, one from each parent Mendel didn’t even know about chromosomes when he made this rule Each organisms has two sts of chromosomes, and so a genetic locus occurs twice in a cell—the two alleles might be the same at that locus (P generation) or they may be different (F₁ hybrids) o 3. If the two alleles at a locus differ, then one, the dominant allele, determines the organism’s appearance; the other, the recessive allele, has no noticeable effect on the organism’s appearance o 4. Law of segregation—the two alleles for a heritable character segregate (separate) during gamete formation and end up in different gametes Egg or sperm only gets one of the two alleles—this happens because chromosomes segregate in meiosis—if the organism is true-breeding and has identical alleles for that character then that allele is present in ALL gametes If different alleles are present (like in the F₁ hybrids) then 50% of the gametes get the dominant and 50% get the recessive Punnett square—handy diagrammatic device for predicting he allele compostion of offspring from a cross between individuals of known genetic makeup o capital letter symbolizes dominant allele, lowercase symbolizes recessive Mendel’s model accounts for the 3:1 ratio of traits he observed in the F₂ generation Useful Genetic Vocabulary Homozygous—and organism that has a pair of identical alleles for a character o Ex PP or pp o “breed true” because all of their gametes contain the same allele o If we cross dominant homozygotes with recessive homozygotes every offspring will have two different alleles Pp Heterozygous—an organism that has two different alleles for a gene because of different effects of dominant and recessive alleles, an organism’s traits don’t always reveal its genetic composition o phenotype—an organism’s appearance or observable traits note that this can mean physiological traits like a pea that lacks the ability to self pollinate vs. one that can pollinate as well as actual physical looks like color o genotype—genetic makeup ex: plants can have same phenotype of purple, but have different genotypes of PP or Pp The Testcross testcross—breeding an organism of unknown genotype with a recessive homozygote—it can reveal the genotype of that organism o ex: if you have a purple flower and you want to know whether it’s PP or Pp, you testcross it and if it was PP all offspring will turn out purple because they’ll all be Pp, but if it was originally Pp, there will be some white ones because there will be at least 1 pp in the mix The Law of Independent Assortment monohybrids—heterozygous for one character o Mendel derived his law of segregation from experiments with monohybrids Mendel identified second law of inheritance by following two characters at the same time o Ex: seed color and shape If you cross two true breeding pea varieties that differ in both characters (ex: yellow round seeds that are YYRR and green wrinkled peas that are yyrr) you will get dihybrids—individuals heterozygous for two characters (YyRr) We know that genes have to independently assort instead of staying together as YR and yr..this means you can get YR, yR, Yr, and yr—we know this because when we had F₁ self reproduce, the F₂ generation got a 9:3:3:1 ratio of results o Alleles of one gene are sorted into gametes independently of the alleles of other genes law of independent assortment—each pair of alleles segregates independently of each other pair of alleles during gamete formation o this law only applies to genes located on different chromosomes (not homologous) genes located near each other on the same chromosome tend to be inherited together and have more complex inheritance patterns than predicted by the law of independent assortment 14.2 The law of probability govern Mendelian inheritance two basic rules of probability can help us predict the outcome of the fusion of gametes in simple monohybrid crosses and more complicated crosses The Multiplication and Addition Rules Applied to Monohybrid Crosses multiplication rule says that in order to determine that probability that two or more independent events will occur together in some specific combination, we multiply the probability of one event by the probability of another o ex: probability that two coin tosses will end up both heads—1/2 (probability that one toss will end up heads) * ½ (probability that the other toss will end up heads) = ¼ (probability that the two tosses will both end up heads) o ex for genes: if two Rr plants reproduce, the probability that the offspring will end up rr is ¼ because there is a ½ chance the egg will have an r and there’s a ½ chance the sperm will have an r and ½ * ½ = 1/4 same for RR—this is the rule we use to figure out that probability of an F₂ plant from a monohybrid cross being homozygous addition rule—the probability that any one of two or more mutually exclusive events will occur is calculated by adding their individual probabilities o this is how we find the probability of a F₂ plant being heterozygous ex: ½ (probability that mother will give r) * ½ (probability that father will give R) = ¼ (probability that there will be Rr) you can also get heterozygous if father gives r and mother gives R—1/2 (probability that mother will give R) * ½ (probability that father will give r) = ¼ ¼+¼=½ Solving Complex Genetics Problems with the Rules of Probability We can use the multiplication rule to find probabilities: o Ex: YyRr— ¼ chance it will be YY, ½ chance it will be Yy, ¼ chance it will be yy; ¼ change it will be RR, ¼ chance it will be rr, ½ chance it will be Rr This means probability of YYRR will be ¼ * ¼ = 1/16; probability of YyRr is 1/2 * ½=¼ o For more examples see pg 271 at the top! 14.3 Inheritance patterns are often more complex than predicted by simple Mendelian genetics Mendel went off the assumption that there were two alleles, one completely dominant and the other completely recessive, but it’s even more complex than that Extending Mendelian Genetics for a Single Gene Deviation from Mendelian patterns occurs when alleles aren’t completely dominant or recessive, when a particular gene has more than two alleles, or when a single gene produces multiple phenotypes Degrees of Dominance Complete dominance—when the phenotype of the heterozygote and the dominant homozygote are indistinguishable Incomplete dominance—when neither allele is completely dominant and so F₁ hybrids have a phenotype somewhere between those of the two parental varieties o Ex: red plus white snapdragons makes pink snap dragons—you know however that it’s not blending because they still produce 1 all red and 1 all white along with the 2 pink Codominance—the two alleles both affect the phenotype in separate, distinguishable ways o Ex: M and N on blood cells—at a single gene locus two variation are possible Individuals can either be homozygous MM, homozygous NN, or heterozygous MN (where red blood cells have both M and N) It’s not intermediate between M and N phenotypes (like complete dominance is) but rather both M and N phenotypes are exhibited since both molecules are present The Relationship between Dominance and Phenotype Dominant alleles don’t subdue a recessive allele—in fact they don’t interact at all, and it is only in the pathway from genotype to phenotype that dominance and recessiveness come in to play Illustration of relationship between dominance and phenotype: o Dominant allele for round pea produces an enzyme that makes starch so when the seed dries, it’s not wrinkled while the recessive allele codes for a defective form of this enzyme One dominant allele results in enough of the enzyme to make enough of the starch, which is why homozygous dominant and heterozygous have the same phenotype For any character, the observed dominant/recessive relationship of alleles depends on the level at which we examine the phenotype o Ex: Tay-Sachs disease—an inherited disorder in humans in which the brain cells of a child cannot metabolize certain lipids because a crucial enzyme doesn’t work right and as the lipids accumulate in brain cells, the child begins to suffer seizures, blindness, degeneration of motor skills and eventual death At organismal level it is recessive because only children who inherit two copies of the alleles have it At biochemical level it is characteristic of incomplete dominance because the activity level of the lipid metabolizing enzyme is intermediate between that in people with homozygous for the normal allele and those with Tay-Sachs disease At the molecular level the normal allele and the Tay-Sachs are codominant because the heterozygous individuals produce equal number of normal and dysfunctional enzyme molecules (the number of normal produces is sufficient so that a heterozygote doesn’t have Tay-Sachs disease Frequency of Dominant Alleles Dominant allele is not always the most popular—oftentimes most people are recessive Multiple Alleles Most genes exist in more than two allelic forms o Ex: ABO blood groups in humans—blood can be A, B, AB, or O Pleiotropy Pleiotropy—when genes have multiple phenotypic effects o Most genes are this Pleiotropic alleles are responsible for the multiple symptoms associated with certain hereditary diseases Extending Mendelian Genetics for Two or More Genes Dominance relationships, multiple alleles, and pleiotropy all have to do with the effects of the alleles of a single gene, but now we look at situations in which two or more genes are involved in determining the phenotype Epistasis Epistasis—when a gene at one locus alters the phenotypic expression of a gene at a second locus o Ex: in mice black fur (BB) is dominant to brown, but C decides if there will be color, so if mice are cc then they have a white coat and it doesn’t matter whether it’s BB or bb at the other allele The gene for pigment (C or c) is epistatic to the gene that codes for black or brown (B or b) Polygenic Inheritance Quantitative characters—characters that vary in the population along a continuum o Ex: human skin color and height Polygenic inheritance—an additive effect of two or more genes on a single phenotypic character (opposite of pleiotropy where one gene is affecting several phenotypic characters) o Although it’s more complicated, even if there were just three genes that controlled skin color (ABC) there could be tons of variation from very dark (AABBCC) to very light (aabbcc) These genes have a cumulative effect and each makes the same genetic contribution (three units) to skin darkness Nature and Nurture: The Environmental Impact on Phenotype Another departure from Mendelian genetics is when the phenotype for a character depends on environment as well as genotype o Ex: wind and sun exposure does something to trees, exercise alters builds of humans, etc. Norm of reaction—the phenotypic range that occurs due to all the possibilities of environmental influences o Sometimes norms of reaction have no breadth (ex ABO blood group system—you can’t change that) and some have very wide breadth (count of red blood cells varies a lot depending on altitude, physical fitness, and infectious agents o They’re generally broadest for polygenic characters because environment contributes to the quantitative nature of these characters Multifactorial—when many factors, both genetic and environmental, collectively influence phenotype Integrating a Mendelian View of Heredity and Variation Phenotype can refer to specific characters as well as to an organism in its entirety Genotype can refer to alleles for a single genetic locus or it can refer to the organism’s entire genetic makeup 14.4 Many humans traits follow Mendelian patterns of inheritance Pedigree Analysis Pedigree—a collection of information about a family’s history for a particular trait and the assemblage of this information into a family tree describing the traits of parents and children across the generations see figure 14.15 to see how to trace through a pedigree helps calculate the probability that a child will have a particular genotype and phenotype Recessively Inherited Disorders The Behavior of Recessive Alleles an allele that causes a genetic disorder codes either for a malfunctioning protein or for no protein at all o if a disorder is recessive, the heterozygotes are normal in phenotype because one copy of the normal allele produces a sufficient amount of the specific protein—person can only get it if they inherit two recessive alleles carriers—heterozygotes who may transmit the recessive allele to their offspring most people with recessive disorders have parents who are carriers of the disorder but have a normal phenotype themselves genetic disorders aren’t even distributed among all groups of people o in olden times people reproduced within a small area so the gene was more likely to be passed on, so for example Ashkenazic Jews have the Tay-Sachs disease occurring 100 times more than non Jews or Mediterranean Jews when disease causing recessive allele is rare, it’s mostly unlikely that two people will reproduce who both carry that allele, but if you mate with someone in your family or someone with the same ancestor as you not too long ago, the chances increase exponentially o so rules society has about marriage between close relatives might have evolved aout of observation that stillbirths and birth defects are more common when the parents are closely related Cystic Fibrosis cystic fibrosis—genetic disease that strikes one out of every 2,500 people of European descent o 1 in 25 are carriers Normal allele for gene codes for membrane protein that functions in transport of chloride ions between cells and extracellular fluid—when you have two recessive alleles you have cystic fibrosis and the protein doesn’t exist so mucus around lungs becomes stickier than usual and it’s way hard for your body to fight infections o If left untreated people with it die before their 5th birthdays, but there’s medicine now that helps people survive longer Sickle-Cell Disease Sickle-cell disease—most common inherited disorder among people of African descent—affects one out of every 4 African Americans cause by substitution of one amino acid in hemoglobin protein; when oxygen content is low in blood, the sickle cell hemoglobin molecules aggregate into long rods that deform the red cells into a sickle shape o these cells may clump and clog small blood vessels which leads to physical weakness, pain, organ damage, and even paralysis regular blood transfusions prevent brain damage and medicine helps prevent or treat other problems, but there’s no cure to sickle-cell two sickle-cell alleles are necessary to have full blown disease, but heterozygotes can experience some symptoms too during long periods of reduced blood oxygen o this is an example of how at the organismal level, the normal allele is incompletely dominant to the sickle cell allele, but at the molecular level the two alleles are codominant because both normal and abnormal hemoglobins are made Dominantly Inherited Disorders they’re much less common because all lethal alleles arise by mutations in cells that produce sperm or eggs, but if a lethal dominant allele causes death of offspring the allele won’t be passed on, whereas if it’s recessive the parent doesn’t show signs of it so they mature and produce and pass it on Huntington’s Disease sometimes lethal dominant alleles don’t become apparent until after the person who has it is old, and they’ve already had kids and may have given the allele to their child o ex: Huntington’s disease—a degenerative disease of the nervous sytem that’s cause by a lethal dominant allele and has no obvious phenotypic effect until the individual is about 35 to 45 years old once deterioration begins it’s irreversible and fatal affects one in 10,000 people Multifactorial Disorders many diseases—heart disease, diabetes, cancer, alcoholism, etc.—are multifactorial, which means there are genetic components and a significant environmental influence Genetic Testing and Counseling Counseling Based on Mendelian Genetics and Probability Rules we can use Mendel’s laws to predict possible outcomes of mating and see if people will have an afflicted baby Tests for Identifying Carriers key is finding out whether parents are carriers but there are ethical dilemmas Fetal Testing amniocentesis—procedure to determine beginning at the 14th to 16th week of pregnancy whether or not the fetus has the disease o done by using amniotic fluid chorionic villus sampling (CVS)—does the same thing, but sample is taken from the placenta o this is much faster because these cells are derived from the fetus and have the same genotype and they’re proliferating rapidoly enough to allow karyotyping to be carried out immediately as opposed to amniocentesis which has to be cultured for several weeks Newborn Screening some genetic disorders can be detected at birth o ex: PKU—kids can’t metabolize phenylalanine and it accumulates to toxic levels in the blood causing mental retardation—if it’s caught at birth though precautions can be taken to allow normal development

![Biology Chapter 3 Study Guide Heredity [12/10/2015]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006638861_1-0d9e410b8030ad1b7ef4ddd4e479e8f1-300x300.png)