Redesign of a Model of Managerial Employee Turnover

advertisement

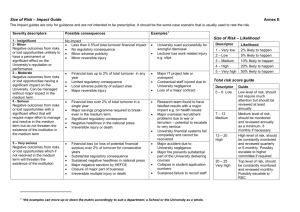

1 Redesign of a Model of Managerial Employee Turnover Shari L. Peterson Associate Professor Department of Organizational Leadership, Policy, and Development College of Education and Human Development University of Minnesota peter007@umn.edu 612-624-4980 Huh Jung Hahn Graduate Assistant Department of Organizational Leadership, Policy, and Development College of Education and Human Development University of Minnesota hahnx225@umn.edu Christina Stello Graduate Assistant Department of Organizational Leadership, Policy, and Development College of Education and Human Development University of Minnesota stel0034@umn.edu 612-709-3705 Bruce A. Center Coordinator, Office of Research Consultation & Services College of Education and Human Development University of Minnesota Cente001@umn.edu 612-624-6886 and Laura Le Research Assistant, Office of Research Consultation & Services College of Education and Human Development University of Minnesota free0312@umn.edu 612-624-6083 Amanuel Medhanie Research Assistant, Office of Research Consultation & Services College of Education and Human Development University of Minnesota medha001@umn.edu 612-624-6886 Stream: #3 Critical, Theoretical, and Methodological Issues in HRD Type: Work in Progress Key Words: Employee Turnover, Longitudinal SEM, Theoretical Model 2 Abstract Previous as well as current literature consistently argues that studies of employee turnover need to be longitudinal. The purpose of this work in progress was to reexamine a longitudinal model using structural equations modeling (SEM) to determine if it remains valid in predicting turnover. With a sample of over 1400 managerial employees in retail and government agencies, the results of both models confirmed the predictive power of the model. Initial intention, goals, commitment, and satisfaction and Career decision-making self-efficacy significantly contributed to Overall Integration which comprised Performance, Social, Career-path, and Extra-organizational integration. Overall integration forged a direct path to the actual Turnover decision in both samples. To date, implications for HRD appear to be strong in terms of the need to create a culture in which managers perceive a sense of connectedness with their work unit, leadership, and peers, and one in which there are opportunities for career growth as well as work-life balance—these dimensions may be conducive to retaining talented managers. However, there also were some curious findings that need to be explored further before the model can be reaffirmed as representing a predictive theory of managerial turnover. Redesign of a Managerial Employee Turnover Model The literature consistently has argued that studies of employee turnover need to be longitudinal if, legitimately, they are to measure an organization’s impact on employee decisions to stay or leave an organization; and they continue to do so (e.g., Steel, 2002; Joo, 2010; Moen et al. 2011). One such longitudinal model, The Organizational Model of Managerial Employee Persistence (Peterson, 2004), was operationalized; the resulting Organizational Integration Survey of Managerial Employees was found to be a valid instrument to measure employee turnover utilizing logistic regression (Peterson, 2007; 2009). However, the instrument was lengthy, and did not include economic or other dimensions outside the control of the organization, as have other researchers (e.g., Hom and Griffeth 1995; Swider et al 2011). For example, Hom and Griffeth (1995) suggested labor market dimensions as a predictor of turnover and Swider et al. (2011) included job alternatives outside organizations as a mediator between job search and turnover. In the intervening years, other new variables have emerged such as employee well-being (Wright and Bonett 2007), organizational justice (Radzi et al. 2009), and perceived organizational learning cultures (Joo, 2010). Clearly, the turnover issue has not been resolved and the problem remains: employee turnover is expensive. The costs are especially high to replace managerial expertise, knowledge, and skills (Abbassi and Hollman 2000; Peterson, 2007; Moynihan and Landuyt 2008). In fact, the cost to replace a manager can range from 70-200% of salary (O'Connell and Kung 2007), and replacement costs are not the only costs associated with excessive turnover. Turnover also has an adverse impact on job performance (Zimmerman and Darnold 2009), lost productivity (Moynihan and Landuyt 2008), and development of the managers who remain (O’Connell and Kung 2009). For example, Moynihan and Landuyt (2008) noted the indirect cost of strain on HRD professionals for the performance improvement and training of those managers who remain. Finally, regardless of the numerous studies on the topic, no additional sophisticated longitudinal designs have emerged. 3 Therefore, considering continued calls for longitudinal studies measuring actual turnover (as opposed to the often used surrogate, intention to stay or leave), and given that such a model and instrument already exist, the purpose of the current study is to reexamine that model to determine if it remains a viable approach. Thus, the research questions are: How viable was the Peterson (2004) model and instrument in predicting turnover? Is there a need to modify the model and/or instrument? 1 Literature Review 1.1 The Organizational Model of Employee Persistence The purpose of Peterson’s (2004) theoretical model, the Organizational Model of Employee Persistence, was to clarify the impact of organizational practices on employee turnover and provide a foundation for research and theory development on employee turnover from an HRD perspective. This model addressed the shortcomings of previous models by (a) calling attention to the magnitude of the role of the organization, (b) including dimensions that represented supervisory relationship, career planning, and career decision making, (c) longitudinally extending to the actual turnover decision, and (d) hypothesizing the symbiotic and reciprocal relationship between organizational variables and individual variables. As noted above, although the model was grounded in the theoretical foundations of turnover, socialization, and educational attrition, it was not all-inclusive. For example, it did not include such external environmental influences as the economic situation or the internal dimension of salary. However, according to Peterson (2004, 2007, 2009), these omissions were intentional the focus was on internal organizational behaviors in order to address factors over which the organization has substantial control and over which HRD can play a critical role. The Peterson (2004) model included individual pre-entry attributes of the employee (such as demographic variables, abilities, skills, behavioral attributes, and career decision-making self-efficacy) but focused on the role of the organization in integrating employees into the performance, social, career-path, and extraorganizational systems of the organization that might influence the individual’s intention, goals, commitment, and satisfaction. Intention, goals, commitment, and satisfaction were represented twice – once at entry into the organization and then after socialization and integration into the organization. Hypothetically, the greater the employees’ integration, the greater would be their developed intention, goals, commitment, and satisfaction, and thus, the greater their likelihood of persisting. This model was operationalized by a 79-question survey and tested in 2007 with retail managers and in 2009 with government employees. The results of both studies provided sufficient support for the model. However, Peterson (2009) made several recommendations to (a) fine-tune and further investigate the factor structure, potentially in order to reduce the number of items, (b) re-examine the two sub-categories of both Performance Integration and Organizational Integration, potentially to collapse into a single dimension of each, (c) re-think the time-consuming nature of the longitudinal nature of the model, and (d) engage in further studies in both the public and private domains. 1.2 Current Literature 4 Peterson had conducted thorough reviews of the literature through 2008 and into 2009, so the literature review for this research in progress focuses on some of the relevant literature from 2009 to present. Much of the recent literature provides support for the Peterson model and the variables related to organizational experience (i.e., Performance, Organizational, Career, and Extra-organizational integration). One recent study found that employees exhibited the highest organizational commitment when they perceived a higher learning culture and when they were supervised in a supportive fashion; this higher organizational commitment explained about 40% of the variance in turnover intention (Joo, 2010). Joo noted limitations of his study including not investigating actual turnover data, and thus called for a longitudinal study to substantiate his conclusions. Chalofsky and Krishna (2009) addressed extra-organizational integration, suggesting that organizations that attempt to foster affective commitment must in turn show their commitment to employees by providing supportive work environments. They noted that the American workforce wants to be part of an organization that will take care of them and help them take care of their families, support their growth through skill and knowledge development, understand their need to have some work-life balance, and use their skills and abilities in a way that is meaningful. Opportunities in the realm of career growth and development represent another key variable in Peterson model—career integration. Preenen et al. (2011) also addressed the importance of career paths, finding that challenging assignments at work served as developmental opportunities that were negatively related to turnover intension. Similarly, with a sample of 264 managerial employees from manufacturing companies, Kraimer et al (2011) found that turnover increased when employees perceived that work assignments and job opportunities within the organization were not consistent with their career interests and goals. Steel (2002) argued that although turnover theories constantly call for longitudinal research, little empirical research has been conducted. Little has changed in the last decade; the current literature continues to call for longitudinal research designs. Even using a longitudinal design, Moen et al’s (2011) study of turnover intentions noted that collecting data for eight months still was too short a timeline. In summary, the past and current literature confirms the need for employee turnover studies to be longitudinal and to include the actual decision to stay or leave (as opposed to a surrogate measure). This was the rationale for re-examining the Peterson model since that model and the instrument used to operationalize the model included those exact features. Furthermore, the independent variables identified in current studies did not vary substantively from the variables used in the instrument being reexamined. 2 Method This work in progress reports the findings based on structural equations modeling (SEM), in response to the need for a more sophisticated picture of the strength of the variables that have been found to play a role in managerial employee turnover among retail organizations and government institutions. In addition to descriptive statistics, correlations between the various dimensions represented in the instrument will be reported. The findings based on these measures could be used to 5 identify (a) the extent to which the lengthy instrument that operationalized the model might be shortened from its current 79 items, (b) whether some sections of the model could be eliminated altogether, and most importantly, (c) the extent to which the predictive power of the model and instrument is reaffirmed or rejected. Table 1 Independent Variables S1 S4 S7 S10 S13 S16 S17 S18 Independent Variables Initial Intention, Goals, Commitment, and Satisfaction Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy (confidence in career information gathering and decision-making) Performance Integration (interactions with managers) Organizational Integration (social aspects and interactions with co-workers) Career Integration (opportunities to discuss career paths with supervisors) Extra-Organizational Integration (degrees of work-life balance) Overall Integration (collective score of Scores 1-16) Developed Intention, Goals, Commitment, and Satisfaction (identical to S1 but collected several months after the initial survey) The independent variables are reported as scores (S) as replicated in the instrument and are identified in Table 1. A single dependent variable (S20) identified whether managers were still employed in their organization one year following completion of the surveys in three retail organizations and three government service institutions. 3 Preliminary Findings Simple descriptive statistics identified that among the four mean integration scores as measured on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 5, the level of Performance Integration was rated highest both by government institutions (3.97) and retail organizations (4.05). Table 2 also identifies that Career Integration was rated lowest by both government institutions (3.24) and retail organizations (3.17). However, across all scores—the four integration scores, plus Initial Intention, Goals, Commitment, and Satisfaction, and Career Decision-making Self-efficacy— government institutions rated Initial Intention, Goals, Commitment, and Satisfaction highest (4.31), followed by Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy (4.05). This was the identical finding for retail organizations, rating Initial Intention, Goals, Commitment, and Satisfaction highest (4.31), also followed by Career Decision-Making Self-Efficacy (4.13). These findings are important because they influenced the initial construction of the structural equations models for both samples. 6 Table 2 Descriptive Statistics n mean S.D. 681 681 4.31 4.05 0.56 0.57 675 676 677 677 677 3.97 3.65 3.24 3.73 3.65 0.48 0.55 0.74 0.55 0.48 527 528 4.31 4.13 0.60 0.58 472 474 474 474 474 4.05 3.78 3.17 3.66 3.66 0.51 0.58 0.80 0.64 0.52 Government Institutions Initial goals, commitment. . . Career decision-making selfefficacy Performance integration Organizational integration Career integration Extra-organizational integ. Overall integration Retail Organizations Initial goals, commitment. . . Career decision-making selfefficacy Performance integration Organizational integration Career integration Extra-organizational integ. Overall integration The correlation matrix (see Table 3) identified moderate to high correlations between all of the independent variables (S1-S16). When analyzing only the integration scores (S 7- 16), the highest correlations were between Performance Integration and Social Integration (r = .656) and between Career Integration and Social Integration (r = .622). This information also contributed to the initial construction of the SEM. Table 3 Correlations Between Main Scores* S S1 S4 S7 S10 S13 S16 Initial Goals (S1) .366 .377 .282 .186 .249 CDMSE (S4) .505 .359 .370 .323 Performance Integration (S7) .656 .525 .481 Organizational Integration (S10) .622 .502 Career Integration (S13) .494 ExtraOrganizational Integration (S16) 7 * All correlations were significant (p =.000) A separate SEM model (using MPLUS V.5) was constructed for the retail sector and for the government institutions. In addition to identifying the path model to the dependent variable that emerges, two statistics are particularly important to the goodness of fit of the model— Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Root Mean Square Approximation (RMSEA). CFI ranges from 0 to 1, and the closer to 1, the more robust. On the other hand, the lower the RMSEA score the better, and it should be less than .06.) For the retail sector (See Figure 1), initial findings identified a path model with a CFI of .987 and RMSEA of .048. The independent variable, Overall Integration, significantly and directly explained the decision of retail managers to stay (.07). As . expected, Initial Intention, Goals, Commitment, and Satisfaction (S1) provided a direct 0 path (.28) to Integration as did Career decision-making Self-efficacy (.38), and all of the 2 separate integration scores, the highest of which was Career Integration (S13). Surprisingly, Developed Intention, Goals, Commitment, and Satisfaction (a longitudinal variable, S18), was not significant, and was the only variable in the model not to have a direct or even indirect path to the turnover decision (S20). Overall, the model accounted for most of the variability, and the goodness of fit suggests that it is a plausible model. The model tested with managers in governmental agencies also was found to be plausible with an even higher CFI (.997) and lower RMSEA (.025). All of the variables significantly interacted, and, the path scores suggest that all of the variables are important, (See Figure 2). As expected, Developed Intention, Goals, Commitment, and Satisfaction (S18) forged a significant and direct .path (.17). Most interesting is that . . while Overall Integration also directly predicted the turnover event, the path was 0 0 negative (-.13), such that overall integration results in being less0 likely- to stay. Thus, 6 5 within the government sample, the greater the managers’ integration, 2 . the greater their likelihood of leaving. As in the retail sample, the greatest contributor to Overall . 0 Integration was Career Integration (S 13), also followed by Performance Integration (S7; 0 2 .95). 2 8 Figure 1. Final path diagram for retail organizations. The '1' is fixed by MPLUS and arbitrary. All the other coefficients are relative to this one. As the largest coefficient, it is clearly and highly significant. ______________________________________________________________________ 9 Figure 2. Final path diagram for government institutions. ______________________________________________________________________ 4 Discussion With a sample of over 1400 managerial employees in retail organizations and government institutions, two separate SEM models (using MPLUS V.5) confirmed that the Peterson model was useful in predicting turnover. The path model for the retail sector was strong with a high CFI of .987 and RMSEA of only .048. All of the independent variables were significant, but only Overall Integration forged a direct path to the decision of retail managers to stay (.07). However, both individual independent variables, Career decision-making Self-efficacy (S4, .38) and Initial Goals, Commitment, & Satisfaction (S1; .28), forged an indirect path—through Overall Integration. Score 1 was the only variable to forge a direct path to more than one variable and that additional variable was, not surprisingly, Developed Intention, Goals, Commitment, & Satisfaction (S18). This preliminary finding clearly needs to be explored further, but perhaps it is in part due to the fact that this variable (S18) was highly significant in forging a rather large path (.51) to Overall Integration. Thus it is also in part. indirectly related to the actual . turnover decision. . 0 0 The model tested with managers in governmental agencies was found to be 0 also 9 5 plausible with an even higher CFI (.997) and lower RMSEA (.025). All of the variables 2 . * significantly interacted, but inconsistent with the retail sample, * Developed Intention, *. *0 2 * 0 2 * 10 Goals, Commitment, & Satisfaction did forge a direct path (.17) to the turnover decision. Inconsistent with the retail sample, Overall Integration directly predicted the turnover event (-.13), but the higher the integration score, the less likelihood of the manager staying in the organization. Government workers are unique in terms of the length of their tenure, the nature of productivity expectations, and the overall organizational culture. While the model itself appears to be supported, the nature of the four integration scores that made up Overall Integration in government institutions need to be examined in greater depth because of this unusual finding. 5 Conclusions and Implications for Research and Practice In recent years, research on organizational commitment, organizational citizenship, and employee turnover has emerged as one of the most important strands of HRD research (Ardichvili, 2011). We began this work in progress with questions about the viability of the Peterson (2004) model and instrument in predicting turnover and whether or the model and/or instrument needed to be modified. Findings to date suggest that the model is reasonably plausible based on strong paths to the turnover decision for both rather large samples. However the research to date has not examined the extent to which the survey might be adapted to make it shorter, thus more efficient. The concern is that the information contained in the items provides rich detail that could be instructive to the HRD and line managers of an organization. To eliminate many of those items for the sake of efficiency, while potentially not reducing the reliability, would reduce the depth of information for the participating organizations. Implications for HRD are strong in terms of the need to create a culture in which managers perceive a sense of connectedness with their work unit, leadership, and peers, and one in which there are opportunities for career growth as well as work-life balance—these dimensions are conducive to retaining talented managers. The model intentionally focused on factors within the organization because these are factors the organization can influence. Using the findings of this study, organizations can focus on strategies to improve managerial retention in the correlated areas. However, given the mixed findings, the role of Overall Integration needs to be clarified. Implications for further research include conducting a new longitudinal study to (a) determine whether the findings of the current SEM can be replicated or whether they are industry specific and (b) assess results during a more challenging economic climate. The initial purpose of re- testing the Peterson model was to find a rationale for revising it; however, it appears to be reasonably plausible as it is. The question remains as to the nature of the different findings in the two samples—curious and unexpected and, while related to the same direct effect on the turnover decision, related in very different ways. 11 References ABBASI, S. and HOLLMAN, K. (2000).Turnover: The real bottom line. Public Personnel Management, 29(3), 333-342. ARDICHVILI, A. (2011). Invited reaction: Meta-analysis of the impact of psychological capital on employee attitudes, behaviors, and performance. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 22(2), 153-156. CHALOFSKY, N. and KRISHNA, V. (2009). Meaningfulness, commitment, and engagement: The intersection of a deeper level of intrinsic motivation. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 11(2), 189-203. HOM, P. and GRIFFETH, R. (1995). Employee turnover. Cincinnati, OH: Southwestern. JOO, B. (2010). Organizational commitment for knowledge workers: The roles of perceived organizational learning culture, leader-member exchange quality, and turnover intention. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 21(1), 69-85. KRAIMER, M. L., SEIBERT, S. E., WAYNE, S. J., LIDEN, R. C. and BRAVO, J. (2011). Antecedents and outcomes of organizational support for development: The critical role of career opportunities. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3), 485-500. MOEN, P., KELLY, E. and HILL, R. (2011). Does enhancing work-time control and flexibility reduce turnover? A naturally occurring experiment. Social Problems, 58(1), 69-98. MOYNIHAN, D. and LANDUYT, N. (2008). Explaining turnover intention in state government. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 28(2), 120-143. O'CONNELL, M. and KUNG, M. (2007). The cost of employee turnover. Industrial management, 14-19. PETERSON, S. (2009). Career decision-making self-efficacy, integration, and the likelihood of managerial retention in government agencies. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 20(4), 451-475. PETERSON, S. (2007). Managerial turnover in retail organizations. Journal of Management Development, 26(8), 770-789. PETERSON, S. (2004). Toward a theoretical model of employee turnover: A human resource development perspective. Human Resource Development Review, 3(3), 209-227. PREENEN, P. T.Y., DE PATER, I.E., VAN VIANEN, ANNELIES E. M. and KEIJZER, L. (2011). Managing voluntary turnover through challenging assignments. Group & Organization Management, 36(3), 308-344. RADZI, S. M., RAMLEY, S. Z. A., SALEHUDDIN, M. and OTHMAN, Z. (2009). An empirical assessment of hotel departmental manager’s turnover intentions: The impact of organizational justice. International Journal of Business and Management, 4(8), 173-183. SHUCK, B., REIO, T. G. and ROCCO, T. S. (2011). Employee engagement: An examination of antecedent and outcome variables. Human Resource Development International, 14(4), 427-445. SWIDER, B. W., BOSWELL, W. R. and ZIMMERMAN, R. D. (2011). Examining the job search-turnover relationship: The role of embeddedness, job satisfaction, and available alternatives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(2), 432-441. 12 STEEL, R. (2002). Turnover theory at the empirical interface: Problems of fit and function. Academy of Management Review, 27(3), 346-360. WRIGHT, T.A. and BONETT, D.G. (2007). Job satisfaction and psychological well-being as nonadditive predictors of workplace turnover. Journal of Management, 33(2), 141-160. ZIMMERMAN, R. and DARNOLD, T. (2009). The impact of job performance on employee turnover intentions and the voluntary turnover process: A metaanalysis and path model. Personnel Review, 38(2), 143-158.