More Debate Examples Logical Fallacies

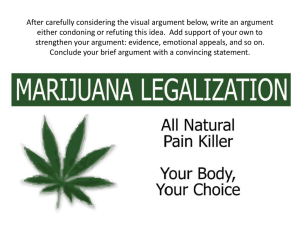

advertisement

More Debate Examples Logical Fallacies Debates are centered on logic and reasoning. Logic and reasoning are the two building blocks upon which effective arguments are built. When an argument appeals to a sense of logic, the case is harder to argue against. To be logically sound, arguments should be supported with evidence. The conclusions should follow from the facts that have been presented. If all debaters were perfect, every argument would be airtight. In reality, people's logic is sometimes imperfect. Debaters sometimes commit logical fallacies. It's up to you to avoid them in your argument and to refute them if used by the opposing team. To successfully refute the ideas of the opposing team, you must know what to argue against. Here are six reasoning errors—called logical fallacies—that are common to debates: • hasty generalizations • false either-or statements • false cause-effect statements • circular reasoning • loaded language • extension Hasty Generalizations Hasty generalizations lack examples. A generalization is a conclusion based on many examples that applies to many things, such as "Most birds can fly." A hasty generalization is the drawing of a conclusion when not enough examples have been observed. For example, you might read a quotation from a property owner who is unhappy about restrictions placed on her land by the Endangered Species Act. If you then conclude that "all property owners oppose the Endangered Species Act," you are making a hasty generalization based on one example. The statement that "all property owners oppose" something would need some kind of reliable, defensible statistic to support this kind of generalization. False Either-Or Statements An either-or statement offers only two possibilities. Some either-or statements are valid, such as, "Either you are awake or you are asleep." The false either-or statement reasons that only two possibilities exist when actually there are more. Here's an example: "Either we convert all cars to hydrogen-powered fuel or we will be unable to stop our dependence on oil." It is true that hydrogen-powered cars do not depend on oil for power; however, other alternatives exist for reducing oil dependency, such as using biofuels, electric cars, riding bicycles, or walking. Sometimes false either-or statements are referred to as "false dilemmas." False Cause-and-Effect Statements A false cause-effect statement assumes that because one event follows or occurs close to another, the first event caused the second. For example, a debater may say driving hydrogen-fuel powered cars is better for human health. She may present evidence that more people are driving hydrogen-fuel powered cars and fewer people are developing migraine headaches. Migraine headaches could be a result of several factors such as diet or stress. To assume that using hydrogen fuel reduces the occurrence of migraine headaches is a false cause-effect statement. Unless a direct link can be shown, the sequence of events is not enough to support the conclusion. Circular Reasoning Circular reasoning says something is true because it is true. In sound reasoning, a statement is supported by facts or evidence. In circular reasoning, a statement is supported only by itself, in different words. It's like saying the same thing twice, but using stronger or different terms the second time. For example, someone might say, "Physical education classes need to stay in school curriculums because kids need to take P.E." This is really a restatement of the idea that physical education classes may be important, but it does not explain why. "Physical education classes need to stay," and, "Kids need to take P.E." mean the exact same thing. The statements lead to each other in an endless circle. Loaded Language In English, synonyms may have the same denotation, or official meaning. However, synonyms with the same dictionary meaning often have different shades of meaning, or connotations. The various connotations of a word often have different emotional values, either positive or negative. For example, slender is a positive term, but scrawny is negative. Loaded language is when a debater uses the connotations of words in a heavily one-sided manner, distorting reality to create an effect. For example, saying that a foreign language requirement would be a "terrible ordeal for students," when actually it would only involve a modest amount of extra work, is loaded language. Extensions Extension is a fallacy of exaggeration. It occurs when a debater exaggerates the meaning of evidence to prove more than it really should or exaggerates the opponent's argument to make it easier to attack. For example, on the issue of whether the government should continue spending money on space exploration, a team argues, "The opposing team supports putting billions of dollars into the space program, leaving no funds to help the millions of homeless children in the nation." The argument is distorted, focusing on the lack of funds to help the homeless rather than whether spending money in space is worthwhile. Focus on the arguments presented and be aware if the other team offers them with a different slant. Review them carefully so you argue the issue that was presented, instead of the argument that was expected. Effective Debating Strategies In addition to researched facts and logical reasoning, the presentation of a clear case is important to win a debate. Here are several strategies that will help you prepare and deliver your arguments effectively. Prepare carefully. Present in a polished and convincing manner. Expose weaknesses with style and strategy. Keep it professional. Prepare carefully. Are your points well-organized? Make strong points at the beginning and end of your argument. Are your points supported with facts and evidence? Just stating something without a source will not convince your opponents. Make sure your sources are solid. Use examples, facts, statistics, expert opinions, and quotes. Have you thought about what the opposing team will argue? Remember to collect facts and evidence that will counter and weaken your opponents' major points. Practice. Before posting your team's response, allow each team member to read and comment on the argument. You may be able to discover a weak spot before the opposing team does. Present in a polished and convincing manner. Make the most of every argument opportunity with a solid presentation. You are the authority. You have carefully researched your position and collected convincing evidence. Present your case with confidence. Stay calm and collected. Avoid getting rattled by your opponents or taking criticism personally. Your manner of expression or tone can give away a lot about your feelings and how you are reacting. Make a solid conclusion. The summary of your points is the last thing to be heard. Firmly state the position you are supporting. Use humor (but avoid silliness). You can gain support by skillfully appealing to your audience's emotions and using humor to gain their support. Expose weaknesses with style and strategy. To win a debate, you must present your position as well as point out flaws in the opposing team's argument. The following tips will help you defend your position and prepare for rebuttal. Beware of pity or emotional appeals. These arguments don't usually have a lot of evidence or facts to support them. Question authority. Are the experts credible that are quoted by the other team? Look for authorities that disagree. Look out for vague arguments. Argument should be clear and precise, statistics should have sources, and sources should be solid. Keep it professional. Beware of distorted or inconsistent facts. Point out any exaggeration of the facts or if the opposing team seems to contradict itself. Remain in the present, not the past. Out-of-date facts such as statistics from a twenty-year-old study would be considered unreliable. Watch out for personal attacks. Using personal attacks or citing issues that are unrelated to the debate are bad manners and bad strategy. Keep the arguments focused on the issues presented, not the personalities involved.