Social Movements Surveillance Neg

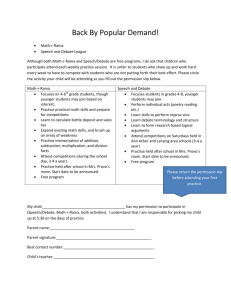

advertisement