Alcohol and other substance use Alcohol disorders at follow up

advertisement

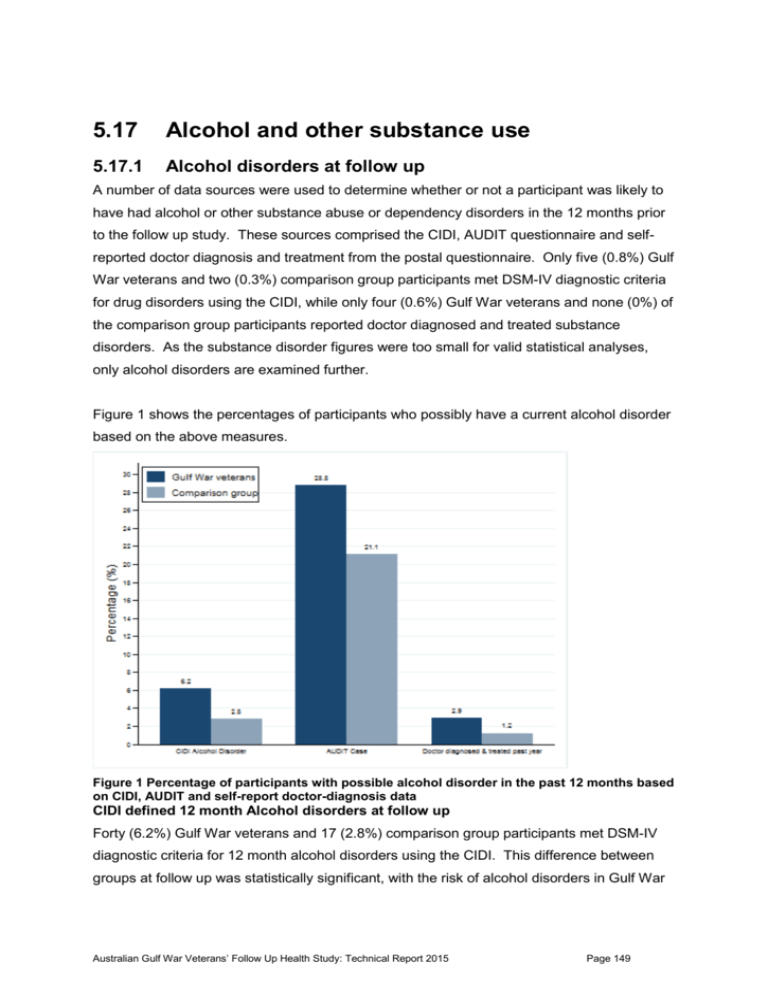

5.17 Alcohol and other substance use 5.17.1 Alcohol disorders at follow up A number of data sources were used to determine whether or not a participant was likely to have had alcohol or other substance abuse or dependency disorders in the 12 months prior to the follow up study. These sources comprised the CIDI, AUDIT questionnaire and selfreported doctor diagnosis and treatment from the postal questionnaire. Only five (0.8%) Gulf War veterans and two (0.3%) comparison group participants met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for drug disorders using the CIDI, while only four (0.6%) Gulf War veterans and none (0%) of the comparison group participants reported doctor diagnosed and treated substance disorders. As the substance disorder figures were too small for valid statistical analyses, only alcohol disorders are examined further. Figure 1 shows the percentages of participants who possibly have a current alcohol disorder based on the above measures. Figure 1 Percentage of participants with possible alcohol disorder in the past 12 months based on CIDI, AUDIT and self-report doctor-diagnosis data CIDI defined 12 month Alcohol disorders at follow up Forty (6.2%) Gulf War veterans and 17 (2.8%) comparison group participants met DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for 12 month alcohol disorders using the CIDI. This difference between groups at follow up was statistically significant, with the risk of alcohol disorders in Gulf War Australian Gulf War Veterans’ Follow Up Health Study: Technical Report 2015 Page 149 veterans estimated to be almost twice as high as the risk in the comparison group (RR 2.21, adj RR = 1.93, 95% CI 1.10 – 3.38). AUDIT caseness at follow up One hundred and ninety-nine (28.8%) Gulf War veterans and 138 (21.1%) comparison group participants met past year AUDIT caseness criteria for possible harmful or hazardous drinking. The difference in levels of AUDIT caseness between the groups at follow up was statistically significant, with the risk of caseness in Gulf War veterans estimated to be around 26% higher than the risk in the comparison group (RR 1.36, adj RR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.05 – 1.52). The relative risk for Gulf War veterans compared with the comparison group was higher for CIDI alcohol disorders than for AUDIT caseness. The AUDIT is a self-report screening instrument for harmful or hazardous levels of drinking or drinking-related behaviour, rather than an actual diagnosis, and so prevalence would be expected to be higher for this measure, rather than for the more comprehensive CIDI DSM-IV diagnosis of alcohol disorders. Self-reported doctor-diagnosis and treatment for alcohol abuse or dependence Twenty (2.9%) Gulf War veterans and eight (1.2%) comparison group participants reported that a medical doctor had diagnosed them with, or treated them for, alcohol abuse or dependency in the period since January 2001, and that they had been treated by a doctor for that condition in the past 12 months. Although the risk of doctor diagnosed alcohol disorders treated in the past 12 months was estimated to be almost one and a half times as high as the risk in the comparison group, this difference between groups at follow up was not statistically significant, (RR 1.45, adj RR = 1.55, 95% CI 0.64 – 2.81), as numbers were small. Similar results were obtained for exact Poisson regression, performed due to small cell sizes. The overall levels of doctor diagnosed and treated alcohol disorder was far lower than that of either CIDI-defined alcohol disorders or AUDIT caseness in both groups, suggesting the possibility of a response bias in not self-reporting diagnoses of alcohol disorder at interview, or not reporting alcohol symptoms to medical doctors in the first place, or doctors missing these diagnoses. Australian Gulf War Veterans’ Follow Up Health Study: Technical Report 2015 Page 150 5.17.2 Association between Gulf War-deployment characteristics and alcohol disorders in veterans at follow up The associations between Gulf War deployment characteristics and occurrence of CIDIdefined 12 month alcohol disorders at follow up in male Gulf War veterans are shown in Table 1. Alcohol disorders at follow up were associated with lower ranks, with the highest risks being observed for other rank – non supervisory, followed by other rank – supervisory, when compared with Officers. The overall differences in risk associated with each rank were statistically significant (p < 0.01). There were not any apparent differences in risk of alcohol disorders between age category (p = 0.21), and service branch (p = 0.93). Table 1 Association between Gulf War-deployment characteristics and 12 month alcohol disorders at follow up in Gulf War veterans Gulf War deployment characteristic Veterans with 12-month alcohol disorders at follow up N n (%) RR Adj RR (95% CI) < 20 58 6 (10.3) 1.0 1.0 20-24 156 13 (8.3) 0.8 1.1 (0.4-2.8) 25-34 336 14 (4.2) 0.4 0.9 (0.3-2.3) >=35 97 7 (7.2) 0.7 2.1 (0.7-6.1) Navy 552 35 (6.3) 1.0 1.0 Army 45 3 (6.7) 1.0 1.2 (0.4-3.7) Air Force 50 2 (4.0) 0.6 0.9 (0.2-3.6) Officer 139 2 (1.4) 1.0 1.0 Other rank-supervisory 330 19 (5.8) 4.0 5.0 (1.3-19.4) Other rank - non supervisory 177 19 (10.7) 7.4 9.7 (2.5-37.4) Age at deployment Service branch Rank category 5.17.3 Change in prevalence, also persistence, remittance and incidence of 12 month alcohol disorder since baseline For male participants who completed the CIDI Alcohol module at both baseline and follow up (n=637 Gulf War veterans and n=555 comparison group), Table 2 shows the change in prevalence of 12 month alcohol disorder, from baseline to follow up, in both study groups. These results indicate that, in the decade or so since the baseline study, the risk of 12 month alcohol disorder in Gulf War veterans approximately doubled, and this was a statistically significant increase. In contrast the risk of alcohol disorder in the comparison group has increased since the baseline study, but not significantly so. Additional analysis showed, Australian Gulf War Veterans’ Follow Up Health Study: Technical Report 2015 Page 151 however, that any difference in risk of developing alcohol disorder across time between Gulf War veterans and the comparison group was not statistically significant (RR 1.13; 95% CI 0.46 – 2.72). Table 2 Prevalence of 12 month alcohol disorders at baseline and follow up for male participants who completed the CIDI at both time points Gulf War veterans (n=637) 12 month Alcohol Comparison group (n=555) Baseline prevalence (%)* Follow up prevalence (%) RR (95% CI) Baseline prevalence (%)* Follow up prevalence (%) RR (95% CI) 20 (3.1) 40 (6.3) 2.0 (1.25-3.20) 9 (1.6) 16 (2.9) 1.78 (0.84-3.76) *Includes only those participants who also completed the CIDI at follow up Table 3 shows the proportions of Gulf War veterans and comparison group participants with a diagnosis (present) or without a diagnosis (absent) of 12 month alcohol disorders at baseline and at follow up. Due to the small cell sizes, exact Poisson regressions were performed. Relatively few of the large proportion (>94%) of Gulf War veterans and comparison group participants who had no diagnosis of 12 month alcohol disorders at baseline, then had this diagnosis at follow up. Incident cases are shown in the first row of data in Table 3, and consist of those participants for whom 12 month alcohol disorders were absent at baseline and present at follow up. The percentage of incident alcohol disorder cases in the Gulf War group (5.3%) was higher than that in the comparison group (2.6%). The adjusted difference between the groups narrowly missed statistical significance, although the unadjusted difference between groups was significant (unadjusted 95% CI 1.09 – 4.22), suggesting that differences were due to possible confounders such as age and military rank when included in the exact Poisson regression model. Persistent cases are shown in the second row of data Table 3, and consist of those participants for whom 12 month alcohol disorders were present at baseline and present at follow up, while remitted cases are those for whom 12 month alcohol disorders were present at baseline but absent at follow up. Of the 20 Gulf War veterans and 9 comparison group members who had a 12 month diagnosis of alcohol disorder at baseline, 35% and 22.2% respectively were persistent cases who met this criteria at follow up, whereas 65% and 77.8% remitted. These differences between groups in persistence and remittance were not statistically significant, but numbers were small and these analyses had limited statistical power. Australian Gulf War Veterans’ Follow Up Health Study: Technical Report 2015 Page 152 Table 3 Persistent and incident cases of 12 month Alcohol disorders among Gulf War veterans and comparison group members who completed the CIDI at baseline and follow up 12-month Alcohol Gulf War veterans Comparison group Follow up n (%) absent n (%) present absent (n = 617) 584 (94.7) present (n = 20) 13 (65.0)‡ Baseline Follow up Baseline n (%) absent n (%) present 33 (5.3)* absent (n = 546) 532 (97.4) 14 (2.6)* 7 (35.0)† present (n = 9) 7 (77.8)‡ 2 (22.2)† Between groups RR Adj RR§ (95% CI) Incidence 2.09 1.85 (0.96–3.77) Remittance 0.84 0.81 (0.28–2.51) Persistence 1.58 1.66 (0.29–16.96) *Incident cases †Persistent cases ‡Remitted cases §These RRs are adjusted for binary age category (<25, >=25), service type (Navy, Army/Air Force) and rank (Officer, nonOfficer) category at August 1990 , using exact Poisson regression due to small cell sizes. 5.17.4 Key findings The risk of current alcohol disorders in Gulf War veterans was significantly higher than that in the comparison group, as ascertained using both DSM-IV CIDI-defined 12-month diagnosis and AUDIT caseness, but not doctor diagnosed and treated alcohol disorders. In addition, Gulf War veterans were twice as likely to have a CIDI diagnosis at follow-up compared with baseline. Among Gulf War veterans, risk of CIDI-defined 12 month alcohol disorders was highest for lower ranks. Since the time of the baseline study, CIDI-defined 12 month alcohol disorders in Gulf War veterans are suggestive of being more persistent, less likely to remit and new cases of alcohol disorders have been more likely to occur relative to the comparison group, although numbers were small and these differences were not statistically significant. Australian Gulf War Veterans’ Follow Up Health Study: Technical Report 2015 Page 153