Walkerton Stations - SVN3MEnvironmentalScience

advertisement

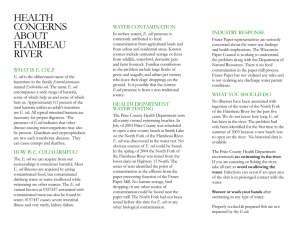

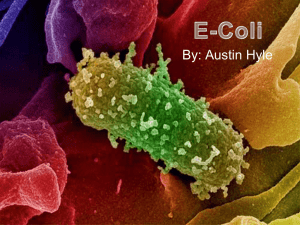

SVN3M Unit 4: Human Health and the Environment Mr. Scott WATER CONTAMINATION IN OUR OWN BACK YARD: Walkerton Ontario STATION # 1: AT YOUR DESK In May 2000 Canadians were shocked by the deaths of at least six people and at least 2000 more who became ill in Walkerton, Ontario, as a result of E.coli contamination of the local water system. Every day countless deaths are reported in the news; the constant flow of stories of death and disaster is such that usually we can distance ourselves from the events. But the deaths of those six people in small-town Ontario had a profound impact on most Canadians. The realization that what happened in Walkerton could happen anywhere in Canada gave the events a significant immediacy and personal relevance. In a wealthy country endowed with bountiful natural resources, the possibility of drinking water being unsafe seems unthinkable. The outbreak in developing countries of dreadful diseases, such as cholera, that kill thousands of people as a result of polluted water, are generally seen as events happening to anonymous people in distant lands. We might feel pity for the sufferers, but the story seems far away because we can't imagine a situation where our own water supply our most basic resource could actually kill us. Walkerton brought this fear home to all Canadians. Water is one of the most fundamental human needs. We can survive weeks without food, but with no water we would be lucky to last a week. In Canada we have always taken fresh drinking water for granted, assuming an endless supply. But fresh drinking water is not as abundant as we might think. Only one per cent of the world's water is drinkable, and although Canada possesses 10 per cent of that water it is constantly being exposed to many forms of pollutants, not just E.coli bacteria. According to water ecologist David Schindler, climate change, acid rain, human and animal waste, ultraviolet radiation, airborne toxins, and biological invaders will endanger all our water supplies within 50 years. The story of Walkerton has also brought to the public's attention the crucial issue of resource management. SVN3M Unit 4: Human Health and the Environment Mr. Scott STATION# 2: MATCH-UP 1. What do officials suspect is the source of the E.coli bacteria that got into the water supply in Walkerton? 2. Why were town officials being blamed? 3. Why was the Ontario government of Mike Harris criticized? 4. The Ontario Government has promised new laws governing water quality standards. However Dr. Murray McQuigge, Walkerton's Medical Officer of Health, is critical of this new plan. Why? 5. What happened in cities and towns across the country after the Walkerton tragedy was widely reported in the media? 6. Why is this a news story that affects all Canadians? McQuigge said: "You can't announce something like that and not have adequate staff to do it," suggesting that regulations are ineffective unless you have enough people to put them into practice. The Walkerton Public Utilities Commission Manager didn't tell anyone about the E.coli contamination until the Medical Officer of Health confronted him with independent laboratory results confirming the contamination. They began to test their water, and a good many of them found that there were problems with their own water quality. Some critics say that Canadians have taken clean drinking water for granted for too long. The Mike Harris government was blamed for years of cutbacks to the provincial budget, privatization of government services, and the downloading of costs from the province to local communities, which some believe had a negative impact on the quality of water standards. Heavy rainfall washed E.coli-contaminated cow manure into one of the three wells from which Walkerton draws its water. SVN3M Unit 4: Human Health and the Environment Mr. Scott STATION# 3: TIME LINE Early April 2000: A chlorinator, used to purify water, begins to break down at the Walkerton Public Utilities Commission (PUC). This is the local organization that is responsible for keeping the water safe. Since there is no back-up chlorinator the manager orders a new one; however, it will take up to two months to arrive. April 7 Provincial environment officials receive a fax from the private lab that tests Walkerton's water saying that four of eight tests indicate that water might be contaminated. Three days later the environment office receives further evidence of possible contamination. The office calls Stan Koebal, the manager of the Walkerton PUC, who tells them the water is fine. April 24 Another round of testing is performed. The results don't indicate any contamination from E.coli. However it is later revealed that the samples were not taken from the well with the damaged chlorinator. Walkerton's water comes from three wells. The well with the poorly working chlorinator was not checked. Once more Koebal tells the environment office that everything is fine. May 15 Koebal sends a further batch of samples to be tested, but to another lab. May 18 The PUC receives a fax from the lab confirming E.coli contamination of Well Seven, the one with the malfunctioning chlorinator. May 19 The region's Medical Officer of Health, Dr. Murray McQuigge, is informed that the local hospital has had several cases of bloody diarrhea, a sign of E.coli poisoning. Koebal assures McQuigge that the water is safe. The Medical Health Office (MHO) therefore begins to look into other causes for the sickness. May 20 As many as 40 more people report to hospital with bloody diarrhea. An anonymous caller telephones the Ministry of the Environment's Spills Action Centre claiming that Koebal has received test results indicating contamination of the water supply. Both Chris Johnston from the Ministry, and McQuigge from the Medical Health Office contact Koebal, who insists that the water is safe. May 21 With more cases of illness reported, the Medical Health Office officially warns residents not to drink the water. The MHO also takes its own independent water samples, no longer trusting the PUC's reports. May 23 The MHO's lab confirms that the water is polluted with E.coli bacteria. McQuigge of the MHO confronts Koebal with the test results. Koebal admits to having received a fax on May 18 that showed that the water had E.coli in it. Health officials are also informed that the chlorinator in Well Seven has not worked for some time. By this time six people who have drunk the water and become ill have already, or will soon, die. At least 2000 others will become ill, many seriously. May 24 McQuigge issues a press release stating that the town officials knew about the problem for nearly a week, and that had they acted on the information sooner, deaths might have been prevented. SVN3M Unit 4: Human Health and the Environment Mr. Scott STATION # 4: What is E.coli? Description: E.coli is short for Escherichia coli. It is a type of bacteria found in the intestines of animals and humans. There are hundreds of different kinds, or strains, of E.coli, some of which are harmful, but most of which are not. The variety that struck Walkerton is known as E.coli 0157:H7. This type produces a powerful toxin, or poison, and can cause severe illness and even death. E.coli 0157:H7 was first identified in 1982 in the United States when 47 people developed severe stomach disorders. The cause of these disorders was traced to ground beef patties that were contaminated with the harmful variety of E.coli. Because E.coli can be caught from eating undercooked contaminated ground beef it has been called the hamburger disease. However, the bacteria can also be caught from consuming unpasteurized milk and apple cider, ham, turkey, roast beef, sandwich meats, raw vegetables, cheese, and of course water. Symptoms: Once infected, people do not necessarily die. Some people develop mild diarrhea. You may even have had a mild strain of E.coli yourself and never realized it! In more serious cases there is severe diarrhea, which is often bloody, as well as very painful stomach cramps. The most severe cases tend to be with young children and elderly people because their immune systems are not as able to fight the infection. In children the infection causes red blood cells to be destroyed, and the kidneys can fail. Even if a child recovers from such a serious illness they may have permanently damaged kidneys and other serious health problems for the rest of their lives. In an elderly patient E.coli can cause strokes, which may kill. However, in most cases people recover with the help of antibiotics after five to 10 days of treatment. Contamination: If E.coli comes from hamburger meat, how does it get into water, you may ask? The answer is through human and animal waste. During heavy rains E.coli in the form of animal manure from farms may be washed into creeks, rivers, streams, lakes, or even groundwater (underground sources of water). Human sewage can do the same thing if it comes into contact with the water sources just listed. When this polluted water is used as a source of drinking water and the water is not treated properly, E.coli may end up in the drinking water as it did in Walkerton. The more manure in the area of water sources, the greater the likelihood that water may become contaminated during flooding. This is why factory farming, as it is called, has been blamed for the water contamination at Walkerton. The good news is that by testing water samples we can find out if water is contaminated with E.coli and then treat the water SVN3M Unit 4: Human Health and the Environment Mr. Scott STATION # 5: What caused the Contamination? 1. A Faulty System of Rules and Regulations? In all bureaucracies it is necessary to have rules and regulations in place so that serious errors do not occur. In the case of Walkerton it seems that the regulations that were in place were not strict enough to prevent a deadly outbreak of E.coli. If this could happen in the richest province in Canada, then it could happen anywhere. Such was the fear of many Canadians, and with this fear they also began questioning whether their various levels of government were adequately protecting them from danger. The tragedy of Walkerton raised the issue of the public's confidence or faith in their governments to act in their interest. It has been suggested that a lack of federal and provincial regulation was responsible, at least in part, for allowing the situation to get out of hand without anybody knowing about it except Stan Koebal, the PUC manager. 2. The Lack of a National Standard? Some environmentalists have called for the federal government to establish a set of binding regulations for water quality that every province would have to follow. Currently, however, water quality standards are basically the responsibility of provincial governments. Federal and provincial governments have co-operated on the federal-provincial subcommittee on drinking water, which regularly updates guidelines for water safety. But these guidelines are not legally enforceable, they are merely suggestions. Each province and territory bases its water safety policy on these guidelines. Only Alberta and Quebec have legislation legally requiring that specific standards be followed province-wide. 3. Cost Cutting? The administration of Premier Mike Harris has been criticized not only for failing to provide a comprehensive system of water standards, but also for shifting the responsibility of water safety to municipalities and reducing the number of government inspectors who check water utilities, in an attempt to cut costs. Before the Harris government came to power in 1995 government labs tested the samples that were sent to them from water utilities, but when the Conservative Party came to power in Ontario they closed all four government labs, and municipal utilities were given the task of testing their own samples using private labs. Had the Walkerton samples gone to a government lab, the trained government staff would presumably have realized the danger and notified the Medical Health Office as well as the Public Utilities Manager. In the case of Walkerton the private lab did tell Stan Koebal about the presence of E.coli, but critics speculate whether Koebal did not realize the importance of this information and therefore did not pass the information on to the MHO. It is important to note that Koebal, like many utilities managers, is not a scientist or engineer. Given that there are many varieties of E.coli that are harmless it may not be surprising that he did not realize the serious danger that it posed. This, critics say, is why it is preferable that labs inform the Ministry of the Environment if they detect tainted water since their employees have much more scientific training. To further cut costs the government ended the obligation of private water labs to inform the government of tainted water. SVN3M Unit 4: Human Health and the Environment Mr. Scott Having eliminated government water testing and also having eliminated the need for private labs to report water contamination to the government, the Ontario Government left the responsibility of water safety in the hands of the municipalities. In the case of Walkerton that came down to one man who made a mistake. There was no procedure for sharing the information among different levels of the government and the public. Had such a procedure been in place the outcome of Walkerton might have been less tragic. 4. The Lack of Timely, Current Testing, and Adequate Staffing? What exactly is in place to regulate the quality of water in Ontario? There is no standard act of government whose rules and regulations all water utilities have to obey. A Crown Corporation known as Ontario's Clean Water Agency oversees about a third of the municipal systems in the province. The province's role in monitoring water quality depends mainly upon water utility inspections by members of the Ministry of the Environment and the Drinking Water Surveillance Program, which tests water in 145 of 627 water utilities, but this provincial body dropped E.coli testing in 1996 due to cutbacks. Aside from this, each of Ontario's 650 municipal water systems carries a Certificate of Approval (COA), which is supposed to outline the municipalities' legal requirements for operating the system. However, some of these certificates date back 40 years, long before the government introduced its new drinking water objectives, which contain the requirements for testing the supply and reporting the contamination. These requirements are not legally binding if they are not written in the certificate. Walkerton's COA was 20 years old. That means there was no legal requirement to report the E.coli hazard to either the Ministry of the Environment or the local Medical Officer of Health. Critics have asserted that without universal standards and up-to-date certification and lacking legal requirements for testing and reporting water conditions, an accident like Walkerton was waiting to happen. SVN3M Unit 4: Human Health and the Environment Mr. Scott STATION #6: Industrial "Factory" Farming So far we have looked at what happened when E.coli got into the Walkerton water system, and how a lack of regulation and enforcement may have contributed to the tragedy, but how did the water become polluted in the first place? It was mentioned earlier that E.coli-contaminated manure was probably the culprit. Remember that on May 12, 2000, there were heavy rains in the area and it is suspected that floodwaters swept E.coli-contaminated pig and cattle manure into a drainage pipe of one of the Walkerton wells. Most small municipalities across the country use groundwater as a source of their drinking water rather than surface water like lakes and rivers, which large cities usually use. Groundwater is water naturally existing in underground reservoirs. Groundwater originates above ground as rain but soaks through the ground into porous channels in the earth. As the water seeps down, the soil acts as a natural filter straining out impurities, which means that most groundwater is of very good quality. To obtain groundwater, municipalities dig wells in the ground and pump the water up. At Walkerton it is suspected that during flooding, contaminated water entered the casing at the top of one of the wells, or a nearby drainage pipe. It was because the bad water entered the pipe that the water supply was poisoned; if the water had just soaked into the soil it would most likely have been purified by the time it became groundwater. The poisoning of water in this manner has brought up the issue of what is called factory farming. It used to be that across the country there were thousands of farmers who might, perhaps, own 100 head of cattle; but in recent years the livestock business has become industrialized, meaning there are fewer farms, but they are much larger. For example, in Alberta there are now only 50 beef producers who control 80 per cent of the province's slaughtered beef. The feedlots where the cattle are kept may hold 25 000 cattle in a space the size of a city block. That many cattle produce a great amount of manure in a small space; manure that is then spread directly on fields. This scenario is pretty much the same everywhere in Canada. Up to now governments across Canada have encouraged factory farming, deeming it highly cost- and revenue-effective. The idea behind it is that by jamming animals together into huge barns farmers will be able to cut costs and sell products more cheaply. Canada's hog business alone is a multibillion-dollar industry that employs 100 000 people. Before Walkerton the Ontario government, among others, was reluctant to regulate the industry, but under continued pressure they have recently allowed municipal governments to ban factory farms on a temporary basis until laws for handling the tonnes of manure they produce are in place. Keep in mind that it has not been proved that the E.coli-contaminated manure came from a factory farm; it may have come from a single small independent farm. Still, the existence of huge unregulated farms generating thousands of litres of liquid manure a day increases the chances of pollution. This type of farming was discussed in a provincial water commission in Quebec that criticized the Quebec government for allowing farmers to contaminate water with manure, pesticides, and fertilizer. Even if it was not the direct source of contamination in the Walkerton tragedy, factory farming does pose a serious threat to the environment. Dr. Murray McQuigge of the Medical Health Office in Walkerton has said that "poor nutrient management on farms is leading to the degradation of the quality of groundwater, streams, and lakes." SVN3M Unit 4: Human Health and the Environment Mr. Scott