Craft Analysis of Markus Zusak`s The Book Thief

advertisement

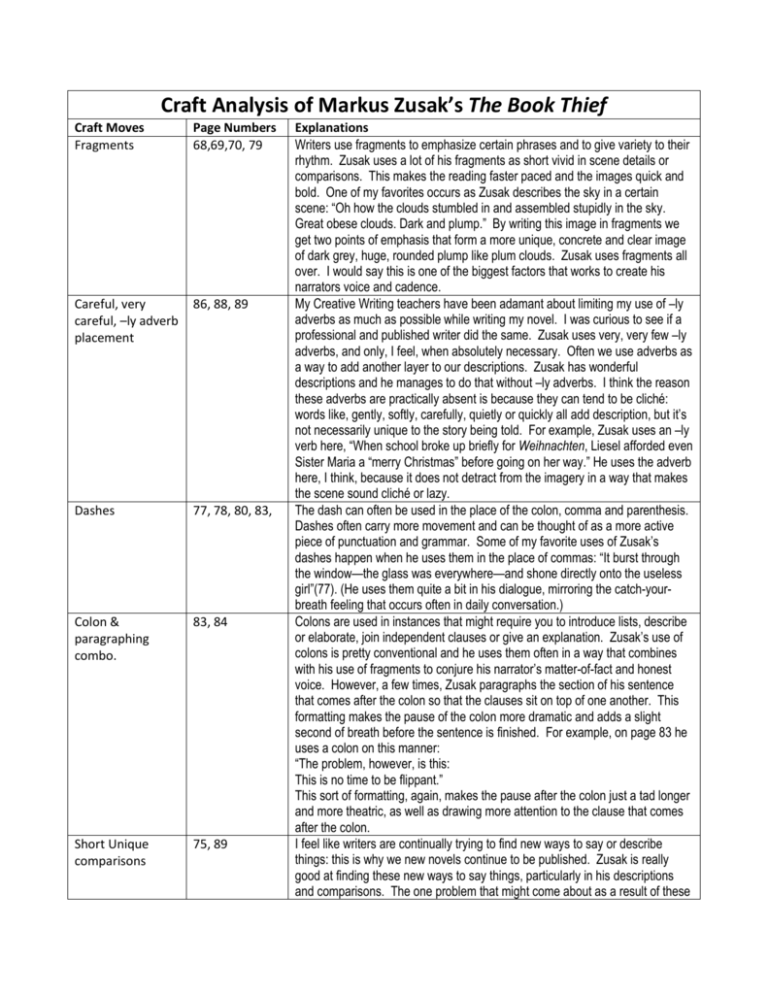

Craft Analysis of Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief Craft Moves Fragments Page Numbers 68,69,70, 79 Careful, very careful, –ly adverb placement 86, 88, 89 Dashes 77, 78, 80, 83, Colon & paragraphing combo. 83, 84 Short Unique comparisons 75, 89 Explanations Writers use fragments to emphasize certain phrases and to give variety to their rhythm. Zusak uses a lot of his fragments as short vivid in scene details or comparisons. This makes the reading faster paced and the images quick and bold. One of my favorites occurs as Zusak describes the sky in a certain scene: “Oh how the clouds stumbled in and assembled stupidly in the sky. Great obese clouds. Dark and plump.” By writing this image in fragments we get two points of emphasis that form a more unique, concrete and clear image of dark grey, huge, rounded plump like plum clouds. Zusak uses fragments all over. I would say this is one of the biggest factors that works to create his narrators voice and cadence. My Creative Writing teachers have been adamant about limiting my use of –ly adverbs as much as possible while writing my novel. I was curious to see if a professional and published writer did the same. Zusak uses very, very few –ly adverbs, and only, I feel, when absolutely necessary. Often we use adverbs as a way to add another layer to our descriptions. Zusak has wonderful descriptions and he manages to do that without –ly adverbs. I think the reason these adverbs are practically absent is because they can tend to be cliché: words like, gently, softly, carefully, quietly or quickly all add description, but it’s not necessarily unique to the story being told. For example, Zusak uses an –ly verb here, “When school broke up briefly for Weihnachten, Liesel afforded even Sister Maria a “merry Christmas” before going on her way.” He uses the adverb here, I think, because it does not detract from the imagery in a way that makes the scene sound cliché or lazy. The dash can often be used in the place of the colon, comma and parenthesis. Dashes often carry more movement and can be thought of as a more active piece of punctuation and grammar. Some of my favorite uses of Zusak’s dashes happen when he uses them in the place of commas: “It burst through the window—the glass was everywhere—and shone directly onto the useless girl”(77). (He uses them quite a bit in his dialogue, mirroring the catch-yourbreath feeling that occurs often in daily conversation.) Colons are used in instances that might require you to introduce lists, describe or elaborate, join independent clauses or give an explanation. Zusak’s use of colons is pretty conventional and he uses them often in a way that combines with his use of fragments to conjure his narrator’s matter-of-fact and honest voice. However, a few times, Zusak paragraphs the section of his sentence that comes after the colon so that the clauses sit on top of one another. This formatting makes the pause of the colon more dramatic and adds a slight second of breath before the sentence is finished. For example, on page 83 he uses a colon on this manner: “The problem, however, is this: This is no time to be flippant.” This sort of formatting, again, makes the pause after the colon just a tad longer and more theatric, as well as drawing more attention to the clause that comes after the colon. I feel like writers are continually trying to find new ways to say or describe things: this is why we new novels continue to be published. Zusak is really good at finding these new ways to say things, particularly in his descriptions and comparisons. The one problem that might come about as a result of these unique comparisons is that they can be a little hard to imagine. But, they do add tone and atmosphere to the novel because he uses very tangible and concrete objects that our mind’s associate with certain settings or emotions. On page 89, “That was when Mama finished her soup with a clank, suppressed a cardboard burp, and answered for him.” What is a cardboard burp? Cardboard is useful, dull brown, wrinkles and smells dank when it’s wet, its superbly versatile, often associated with packaging, it’s essentially thick paper: the feeling we get is a bland sort of homey and versatile burp. Interesting.