2015 Human free will in Aquinas Paris Handout

advertisement

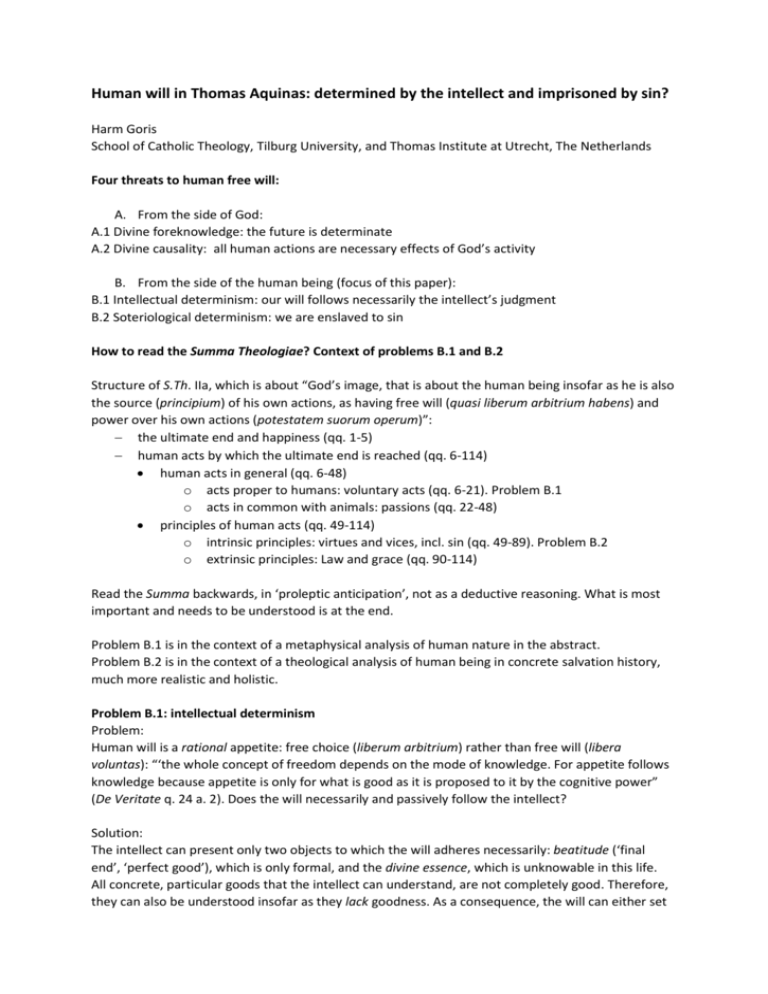

Human will in Thomas Aquinas: determined by the intellect and imprisoned by sin? Harm Goris School of Catholic Theology, Tilburg University, and Thomas Institute at Utrecht, The Netherlands Four threats to human free will: A. From the side of God: A.1 Divine foreknowledge: the future is determinate A.2 Divine causality: all human actions are necessary effects of God’s activity B. From the side of the human being (focus of this paper): B.1 Intellectual determinism: our will follows necessarily the intellect’s judgment B.2 Soteriological determinism: we are enslaved to sin How to read the Summa Theologiae? Context of problems B.1 and B.2 Structure of S.Th. IIa, which is about “God’s image, that is about the human being insofar as he is also the source (principium) of his own actions, as having free will (quasi liberum arbitrium habens) and power over his own actions (potestatem suorum operum)”: the ultimate end and happiness (qq. 1-5) human acts by which the ultimate end is reached (qq. 6-114) human acts in general (qq. 6-48) o acts proper to humans: voluntary acts (qq. 6-21). Problem B.1 o acts in common with animals: passions (qq. 22-48) principles of human acts (qq. 49-114) o intrinsic principles: virtues and vices, incl. sin (qq. 49-89). Problem B.2 o extrinsic principles: Law and grace (qq. 90-114) Read the Summa backwards, in ‘proleptic anticipation’, not as a deductive reasoning. What is most important and needs to be understood is at the end. Problem B.1 is in the context of a metaphysical analysis of human nature in the abstract. Problem B.2 is in the context of a theological analysis of human being in concrete salvation history, much more realistic and holistic. Problem B.1: intellectual determinism Problem: Human will is a rational appetite: free choice (liberum arbitrium) rather than free will (libera voluntas): “‘the whole concept of freedom depends on the mode of knowledge. For appetite follows knowledge because appetite is only for what is good as it is proposed to it by the cognitive power” (De Veritate q. 24 a. 2). Does the will necessarily and passively follow the intellect? Solution: The intellect can present only two objects to which the will adheres necessarily: beatitude (‘final end’, ‘perfect good’), which is only formal, and the divine essence, which is unknowable in this life. All concrete, particular goods that the intellect can understand, are not completely good. Therefore, they can also be understood insofar as they lack goodness. As a consequence, the will can either set them aside or approve them (Summa Theologiae I-II q. 10 a. 2). That is why “the will does not by necessity follow reason” (De Veritate q. 22 a. 15). The will can only choose what the intellect has understood as a good, but need not choose what has been judged rationally the best option, i.e it does not have to make the right choice. Factors that incline the will in making the final choice (cf. De Malo 6): 1. right reason: determines what is rationally the best option. Free: The will can reject it. 2. coincidences drawing the attention of the intellect. Free: The will can ignore them. 3. Most important: innate and especially moral constitution of the person. “As each one is, so the end appears to him” (Nicomachean Ethics 3.5, 1114a32-b1). The good is always good for someone; it must be fitting (conveniens). Summa Theologiae I-II q. 9 a. 2 “That which has been understood as something good and fitting, moves the will by way of an object. However, that an object appears as good and fitting, is because of two things, viz. the condition of the object proposed and the condition of the one to whom it is proposed. For ‘fitting’ is a relative notion and, therefore, depends on both relata. That is why a taste which is differently disposed, will not accept in the same way something as fitting and as not fitting. As the Philosopher says in Ethics III: ‘as each one is, so the end appears to him.’” Moral constitution – what kind of person are you? Determined by the virtues and vices a person has acquired and that shape how his intellectual powers (will and intellect) and his bodily passions function. Free: We can act out of character. Not a hyper-rationalist, but a more holistic model of ethics: embodied and historical: ‘embodied’: human being is animal rationale. Intellectual powers and bodily passions. ‘historical’: human being is animal politicum et sociale. Social-historical context. Problem B.2: soteriological determinism Universal and radical redemption by Christ → doctrine of original sin, transmitted by our ancestors: “slavery of sin”, “law of lust/flesh”. Impairs human free will in choosing the truly good and human will is only set free by grace. Paradise: humankind (Adam and Eve) not created in pure nature, but in a special state of grace, called ‘original justice’: includes sanctifying, supernatural grace and ‘preternatural gifts’, in particular the right harmony between sensory powers, rational soul and God. Original sin: loss of original justice and of “natural inclination to virtue” (Summa Theologiae I-II q. 85 a. 10). All morally relevant human powers severely “wounded”: intellect. Lacks the virtue of prudence. Sin out of negligence concupiscibile. Lacks virtue of temperance. Sin out of concupiscence irascibile. Lacks virtue of fortitude. Sin out of weakness will. Lacks virtue of justice. Sin out of malice Sinful human being remains free, can avoid mortal sin, but not for long. Conclusion 1. Aquinas exegesis: reading Summa Theologiae “in proleptic anticipation” 2. Aquinas’ model of ethics: realistic, holistic, embodied and historical 3. Aquinas’ soteriology: not as dramatical as Luther’s or Heidelberg Catechism; grace is necessary.