Module C- Representation and Text

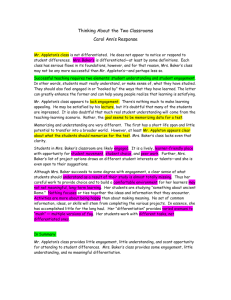

advertisement