Introduction to Conversational-Act Analysis And Its Application to

advertisement

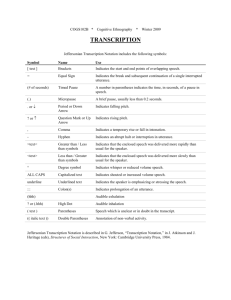

Introduction to Conversational-Act Analysis And Its Application to Social and Private Speech Data Peter Feigenbaum, Ph.D., Fordham University 1. Introduction to Conversational-Act Analysis And Its Application to Social and Private Speech Data The aim of this workshop is to teach you a method for analyzing speech that will enable you to identify the most basic speech acts that a speaker performs every time he or she utters words in a conversation. The decision procedure for analyzing utterances and the classification system for identifying speech acts were developed by my mentor, John Dore (1979). He is the linguist who gave applied speech acts the name “conversational acts”. My reason for teaching you this method is to convince you that a simple but powerful tool exists that can be applied to empirical data to verify and validate Lev Vygotsky’s (19301935/1978, 1934/1987) theory of psychological development. I will work hard to make the relationship between conversational acts and Vygotsky’s theory of the development of words and their meanings as clear as possible. The deal is: if I convince you that conversational-act analysis is an appropriate method for testing Vygotsky’s theory, then you have to promise to start conducting Vygotskian research! Do we have a deal? 2. Part I. Conversational-Act Analysis and Its Application to Social Speech Data 3. 1) Introduction—A Brief History of Speech Acts and Applied Conversational Acts (C-Acts) 4. In a series of lectures that he delivered at Harvard University over 50 years ago, the philosopher of language John Austin (1962) argued persuasively that speech utterances perform actions. Simply by saying certain words, people make claims, take oaths, show respect, apologize, criticize, marry, and initiate a host of other interpersonal and cultural interactions that are too numerous to mention. Austin suggested there could be more than a thousand verbs in the English language that describe the many actions that people perform simply by speaking. What John Austin developed through the course of his lectures was the concept of speech acts. This highly generalized and abstract concept became more articulated and concrete in the able hands of another philosopher, John Searle (1976). Searle extracted the essential features of the concept, developed a taxonomy of types, and articulated the theory necessary to construct a conceptual model. At the center of his model is a speech utterance, which Searle refers to as a locution. When a locution is deployed in conversation, the speaker uses the locution to perform an act (or acts) of communication. The particular form that an utterance takes, plus the tone of voice and the circumstances of its delivery, provide a listener with clues as to the speaker’s intentions. A speaker’s intentions are to produce a speech act. According to Searle, a locution is delivered with an attitude, which he referred to as the illocutionary force. It is the specific features of a locution and its illocutionary force that a listener must attend to in order to recognize the speaker’s speech act. Furthermore, once a listener grasps the speaker’s intended speech act, he or she may also infer that there are obligations or expectations related to the speech act. What response the listener makes to the speech act Searle refers to as the perlocutionary effect. To simplify this model, consider the following analogy between performing a speech act and playing the game of billiards. During one’s turn at billiards, the object is to use the cue stick to apply force to the cue ball so that it bounces off the cushions and strikes the red and green balls. In this analogy, the cue ball 1 represents the utterance, or locution. The utterance is delivered with a measured amount of force, and perhaps with some spin—depending on precisely where the cue ball is struck. This represents the illocutionary force. The intention being, of course, to move the cue ball so that it will contact the green and red balls in a very specific way—namely, in a manner that will set up the next turn. The green and red balls represent the listeners in this analogy. 5. 2) Dore’s System for Classifying Basic Conversational Acts 6. The concept of a speech act that I just described can actually be put to an empirical test using John Dore’s (1979) classification scheme. What Dore did was to take the concept of speech acts and apply it to actual utterances of interpersonal speech. Dore invented the name “conversational acts”, or “c-acts” to distinguish the applied version of speech acts from the conceptual one. 7. He devised a procedure for analyzing children’s speech utterances that enables a researcher to identify the basic speech acts being performed. Notice that there are several basic categories of conversational acts: assertions, requests, expressions, and responses. These are the basic acts that everyone performs when they speak. You can either tell someone about something, ask someone about something, emote to someone about something, or respond to someone about something. And you can do all of these things with just one utterance—if you’re strategic about it. The status of the category “performatives” is still being debated, but Dore (1979) included these particular acts because the children in his experiment performed them. Performatives are acts that one accomplishes simply by saying the right words. “Regulatives” are acts that are useful for keeping conversation flowing smoothly. I need to point out that I believe that a second tier of conversational acts can be and should be constructed on top of the foundation created by these basic categories. I think it will become apparent to you all as we go through some examples that a number of other acts are performed on top of the basic foundation provided by assertions, requests, expressions, and responses. Flirting, deceiving, threatening, joking, avoiding, and criticizing are but a few examples. Thus, there is more work to be done fleshing out a complete taxonomy of conversational acts. 8. One other noteworthy property of this classification scheme is the tight relation between some of the request types and their corresponding response types. In order to respond appropriately in a conversation, a developing child is faced with the difficult task of trying to comprehend the implicit rules of dialogue. With regard to the relationship between one utterance and another in conversation, nowhere is that relationship manifested more clearly than in the relationship between a question and an answer. For that reason, question-answer exchanges may be just the type that children need to grasp the logic of dialogue. I also wish to point out that Dore (1979) introduced the category of “Responses” into the classification system because it is a meaningful category if you study speech acts in real-life conversation. Neither Searle (1976) nor Austin (1962) noticed the need for this category when speech acts were still at a conceptual stage. 9. 3) An Example of the Application of Dore’s Classification System: A Passage from Dostoevsky Now I would like to show you an example of how this classification of basic conversational acts looks when it is applied to data. Rather than presenting typical conversational data where speakers use different linguistic expressions to convey the same C-act, I think it would be far more illustrative to use the rare instance of a conversation involving the exchange of only one linguistic expression that is intended to convey different C-acts. Such an example would provide a real acid test for Dore’s (1979) classification 2 system. Where can we find such an example? In Chapter 7 of Vygotsky’s (1934/1962) Thought and Language, of course, where he quotes a passage from Dostoevsky’s (1873) The Diary of a Writer. Fortunately, Dostoevsky does all of the heavy lifting with respect to determining the communicative intentions of the speakers, leaving to us the easy task of picking the C-acts off the list and simply recording them. The passage describes a conversation among several drunken workmen that consists entirely of one uncouth word. This curse word will be designated in the following example as [expletive]. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. One Sunday night I happened to walk for some fifteen paces next to a group of six drunken workmen, and I suddenly realized that all thoughts, feelings, and even a whole chain of reasoning could be expressed by that one noun, which is moreover extremely short. One young fellow said it harshly and forcefully, to express his utter contempt for whatever it was they had all been talking about. Another answered with the same noun but in a quite different tone and sense—doubting that the negative attitude of the first one was warranted. A third suddenly became incensed against the first and roughly intruded on the conversation, excitedly shouting the same noun, this time as a curse and obscenity. Here the second fellow interfered again, angry at the third, the aggressor, and restraining him, in the sense of “Now why do you have to butt in, we were discussing things quietly and here you come and start swearing.” And he told this whole thought in one word, the same venerable word, except that he also raised his hand and put it on the third fellow’s shoulder. All at once a fourth, the youngest of the group, who had kept silent till then, probably having suddenly found a solution to the original difficulty which had started the argument, raised his hand in a transport of joy and shouted . . . Eureka, do you think? I have it? No, not eureka and not I have it; he repeated the same unprintable noun, one word, merely one word, but with ecstasy, in a shriek of delight—which was apparently too strong, because the sixth and the oldest, a glum-looking fellow, did not like it and cut the infantile joy of the other one short, addressing him in a sullen, exhortative bass and repeating . . . yes, still the same noun, forbidden in the presence of ladies but which this time clearly meant “What are you yelling yourself hoarse for?” So, without uttering a single other word, they repeated that one beloved word six times in a row, one after another, and understood one another completely. (p. 143-144) 18. 4) Dore’s Decision Procedure for Identifying Basic Conversational Acts 19. In the passage I just read, Dostoevsky (1873) interprets the speech acts for us. So what would it take for us to do that interpretive work ourselves? Dore (1979) devised a decision procedure for analyzing children’s speech that enables a researcher to identify the basic speech acts being performed. The analysis is applied to one utterance at a time. The first step begins by determining: a) the literal semantic meaning of the words contained in the utterance, which the philosopher of language Jerrold Katz (1972) articulated in grammatical terms. He described the semantic meaning of a sentence as a logical proposition, composed of a logical subject, a predicate, and modifying phrases. Of course, not all turns at talk are complete sentences, or even complete phrases, but for those utterances that do take the form of a sentence, this is certainly the first step. This part of the analysis answers the superficial question: What did the other person just say? Now it is time to ask the deeper question: What did the other person mean by saying that? Step b) attempts to peel the onion by looking for clues about the speaker’s communicative intentions—in other words, their communicative act. The particular way that grammar is used, or the vocal emphasis that the speaker places on a particular clause or word can be evidence of sarcasm, for example—thus signaling a joke has been made. 3 In step c) the analysis moves on to novel information—anything new that has been introduced either into the conversation or the ongoing activity. The pioneering work of Michael Halliday (1970) revealed the importance of novel information in maintaining joint attention among participants in a conversation. As novelty flows, so flows the topic of attention. Step d) asks the analyst to examine what the speaker has been saying and doing over the past few turns. That information could be relevant to determining the speaker’s communicative intentions. Step e) looks at the interaction. Both the speech and the actions of the participants in relation to one another provide clues that could enable a researcher—or a listener—to recognize one or more of the basic conversational acts. Catherine Garvey (1975) did much of the ground-breaking work to establish an understanding of these relations. Finally, in step f) the analysis shifts to the physical and social and cultural properties of the situation that might have a bearing on the interpretation of the utterance. Here, one would want to consult the numerous communicative channels that speakers conventionally use to convey speech acts: intonational stress on particular words, emotional tone, vocal timber and volume, choice of words and syntax, as well as the relationship of the utterance to the conversational topic, to ongoing activity, the social situational, the physical circumstances—even the participants’ awareness of one another’s knowledge. Lewis (1972) described in detail the sorts of contextual features that could influence the interpretation of an utterance. At this point, an analyst should have enough information to choose a particular conversational act or acts from Dore’s (1979) classification table. 20. 5) An Example of the Application of Dore’s Decision Procedure to Social Speech Data 21. Background: A Social Speech Dialogue [Show SS Episode 1 uninterrupted (full-screen)] [Show SS Episode 1 uninterrupted (minimize screen) – With Transcript in Excel] [Show SS Episode 1 in stop-action (minimize screen) – With C-Act Codes in Excel] 22. 6) A Participatory Exercise—Applying Dore’s Decision Procedure and Classification System [Show Remaining SS Episode 1 uninterrupted (minimize screen) – With Transcript in Excel] [Show Remaining SS Episode 1 in stop-action (minimize screen) – With C-Act Codes in Excel] 23. 7) The Relevance of C-Act Analysis to Vygotsky’s Theory of the Development of Word Meaning The best way I know to introduce to you the dynamic character of Vygotsky’s (1934/1987) theory of word meaning is by marshaling Vygotsky’s own words. 24. He gets right to the heart of the matter in this passage—which we will consider in several pieces. The first line of this passage informs us that the activity of producing words (a.k.a. “speaking”) and the activity of comprehending words (a.k.a., “thinking”) are united by marriage, but that each originates from a 4 different clan. In certain respects they are complete and total opposites, each behaving in accordance with its own laws of motion. The passage highlighted in blue summarizes the ontogenetic direction in which the activity of speaking develops, with particular reference to its linguistic structures. In the portion in red, Vygotsky stumbles a bit, unsure of which linguistic structures to associate with this movement. But his characterization of its direction is clear: The structures of meaning develop in the opposite direction from those of spoken language. Finally, he concludes by making clear that this is a marriage composed of the conflict of opposites. (In terms of linguistic structures, he seems to have settled on the pendulum swinging between word and sentence.) 25. Just so that we’re all absolutely clear about this dynamic, let’s briefly review the relationship. On the “external-vocal-word-speaking” side of the aisle we have the development from “word” to “monologue”. (A monologue is defined as a single turn at talk consisting of two or more sentences). On the “internalsemantic-meaning-thinking” side of the aisle we have structures of meaning that are roughly associated with each linguistic structure. (Forgive me for these descriptions—they are only intended to fill a conceptual slot in this scheme.) Now, for competent adult speakers, the proper match between the linguistic structures on the left and the semantic structures on the right is horizontal. Each line in this table identifies a separate pairing of vocal and semantic forms. 26. But for an infant at the beginning of the developmental process, the meanings to be expressed are global and undifferentiated. Ironically, the only linguistic structures available to communicate this global meaning are the tiniest linguistic structures of all—individual words. 27. The tools for articulating global meaning are supplied as an infant begins to expand his or her linguistic repertoire with the addition of simple phrases. 28. With each new set of structures that develops, speaking and thinking advance. 29. The interpenetration of speaking and thinking becomes deeper as development proceeds. 30. The unity of thinking and speaking is maintained throughout the developmental process, even though the pairing of word and meaning structures is not stable. 31. Stability is achieved only at the end of the developmental process, when the conflict between thinking and speaking reaches a compromise. This compromise is nothing more than the set of social conventions established by the adult speech community. These conventions include the assignment of particular meanings to particular words, rules for sequencing words into grammatical structures, and rules for taking turns and for exchanging speech utterances in conversation. 32. 8) Psychological Subject and Predicate, both Within and Between Conversational Acts I have introduced you to Vygotsky’s (1934/1987) theory of the development of word meaning, but I have not yet demonstrated the relevance of conversational-act analysis to his theory. To do so, I need to drill down to the level of speaking and listening roles, and show how they fit into a dialogue. 5 33. First, the speaker (Person A) produces a speech utterance and the listener (Person B) comprehends it. In dialogue, this “speaking and thinking” unit is followed by another in which the participants switch roles: Person B becomes the speaker and Person A becomes the listener. (We have just encountered our first example of the dialectical pattern: A-B, B-A.) 34. Let’s dig down further. Vygotsky (1934/1987) proposed that the movement from thinking to speaking (and back again) involves traversing five “planes”. Tatiana Akhutina (2003) has done some marvelous work describing these planes. The first step in the formation of an utterance is the emergence of a motive. Second, the crystallization of the general intention—the germ of a thought or a schema. This germ is then expressed in step three as inner speech. The more facile a person is at conducting strategically planned internal conversations, the more options that exist for reflecting backwards upon thoughts and motives, and for thinking forwards toward designing an appropriate speech utterance to fit the situation. The formulation of a speech plan in the motor cortex constitutes the fourth step, while the fifth step consists in carrying out the plan and actually uttering and performing the speech. 35. Listening takes the opposite journey: it begins with the speech produced by another and ends inside the listener’s consciousness. Speaking moves from inside to outside, while listening moves from outside to inside. 36. Okay, let’s draw a box around our first speaking and thinking unit. 37. And since we need two such units for a conversational exchange, let’s put in a second speaking and thinking unit. So, Person A initiates a conversational exchange by producing a speech utterance, and Person B listens and comprehends Person A’s utterance. Then Person B responds to the utterance he or she just comprehended by producing an utterance in return. And the chain continues. 38. Vygotsky (1934/1987) approached the phenomenon of conversational initiation and response from the perspective of what he termed the “psychological subject” and “psychological predicate” of a verbal communication. An utterance (or idea) that is held in consciousness is a psychological subject, whereas an utterance that is produced in response to what is in consciousness is a psychological predicate. According to Bakhtin (1981), every utterance responds to an utterance produced by a prior speaker. This is true regardless of whether the prior utterance was produced moments before or centuries before. Conversely, every listener confronts another person’s utterance as an initiation of a new topic of conversation. The words are the joint focus of attention for both participants, and point at the shared topic of the communication. Thus, speakers relate to utterances as psychological predicates, or conversational responses, whereas listeners relate to the same utterances as psychological subjects, or conversational initiations. 39. But psychological subjects and predicates don’t exist just between utterances; they also exist within utterances. And once again, speakers and listeners confront them from opposite perspectives. Let’s start with the speaker. In producing a speech utterance, a speaker starts with a motive and then conceives of an act of speech communication, or speech act, that will fulfill that motive. This “activity” component of a verbal communication is perceived by the speaker as a psychological subject. It is the thought being held in consciousness at that moment. 6 40. With the help of inner speech, the speaker responds to this topic that is being held in his or her consciousness by conceiving of words or text that will complete the speech act. This component is perceived by the speaker as a psychological predicate. Together, they constitute a complete speech act. 41. Now the process shifts to the listener role. A listener’s task is to reconstruct the entire speech act, beginning with the text or utterance. To the listener, the words constitute the psychological subject. Their literal meaning provides the topical focus of the speech act. 42. Once the listener (Person B) comprehends what was said, he or she must infer—from the available contextual evidence—why it was said. This inner speech query leads to the reconstruction of the entire speech act. 43. Now Person B is holding Person A’s speech act in consciousness, and can’t help forming an involuntary reaction to it. It may take some serious inner speech conversation to decide how to respond. Whatever speech acts Person B decides upon, he or she will perceive that communicative intention as a psychological subject. 44. As all speakers do, they respond to a psychological subject with a psychological predicate—which takes the form of a verbalization. The speech act is completed only when it is put into the form of words to be uttered. 45. The process then shifts again to the listener role, where it repeats. The listener confronts the words first, and must establish the meaning of the verbalization. 46. Once the shared topic has been comprehended, the listener must complete the reconstruction of the speech act, the communicative intention, and if possible, the motive behind it all. I would like to point out that the two main components of a speech act—the oral text and the communicative context—correspond to the two parts of verbal thinking that Vygotsky (1934/1987) termed “meaning” and “sense”. The words, according to Vygotsky, convey the semantic “meaning”, which is the explicit and more or less stable part of the communication. The communicative context in which the words are embedded conveys the “sense”, and is the implicit and more elastic part of the communication that serves to qualify and modify the literal meaning of the text. Gregory Bateson (1972), the noted anthropologist, referred to the textual part of a speech act as the “communication”, and the contextual part as the “meta-communication”— because the context determines how the text is to be regarded or understood. End of Part 1 7 Introduction to Conversational-Act Analysis And Its Application to Social and Private Speech Data Peter Feigenbaum, Ph.D., Fordham University 47. Part 2: Conversational-Act Analysis and Its Application to Private Speech Data 48. 1) A Brief Overview of the Social-Private-Inner-Social Pattern of Speech Development 49. The “unity and conflict of opposites” that characterizes the relationship between word and meaning, or between speaking and thinking, is best understood when it is mapped onto an ontogenetic timeline. That way we can visualize how the developmental process leads to the formation of stages or periods. Just to get oriented, thinking and speaking are independent activities during the first year of life. A child’s first words are evidence that they have become united into one activity—a dialogical activity involving others. The movement from part to whole that is characteristic of speaking is inseparably tied to the movement of thinking, which is from whole to part. Each movement spurs on the other, and each serves as both cause and effect of the other. 50. Here I impose divisions along the timeline representing developmental stages caused by transformations of both a functional and structural nature. The timing of these divisions is approximate, and is based on predictions made by Vygotsky (1934/1987), plus empirical evidence. First, consider the division of speech into two modes of production: interpersonal and personal speech. Interpersonal speech is typical back-andforth conversation. An infant’s induction into this basic mode of speaking and communicating exposes him or her to all of the behaviors associated with social speech dialogue, such as speaking, listening, initiating, responding, and turn-taking. Intellectually, native, biological intelligence based mainly on implicit learning (Reber, 1989) is the dominant cognitive system during infancy. And so it is into that system that the first words become assimilated. But like a Trojan Horse, words will gradually assemble themselves into a powerful force that acts from within. At approximately age 3 (earlier for precocious children), a child’s struggle to reconcile the competing demands of speaking and thinking leads to the creation of an alternative mode of engagement—personal speech. This is speech intended for a person’s own consumption, not for anyone else’s. It is most prevalent during play activities—particularly, socio-dramatic and fantasy-play activities. By conducting interpersonal speech conversations with imagined characters, the young child practices imagining the points of view of the speakers and the listeners. In the early half of the private speech stage, a child’s use of private speech helps to enact the play activity, but ironically, the child is essentially unaware of this fact. When the child does become aware of private speech’s influence, the relationship between private speech and practical activity changes dramatically. From that point onward, the child deliberately invokes private speech in order to regulate both play and problem-solving activities. This is possible because private speech—like social speech—has the power to steer the speaker’s attention toward any topic—even a task analysis. With the help of this speech, a child acquires the ability to plan the solution to problems. But solving problems out loud using conversation addressed only to oneself is socially disruptive, particularly if the task is interpersonal speech communication. Some conversations require that participants analyze what they heard, reflect on the implications, and then plan an appropriate response. There is recent 8 evidence that school-age children engage in private speech problem-solving right in the middle of a challenging interpersonal speech communication task. But there is also evidence that children learn to inhibit the respiratory component of the act of vocalization soon after age 4. According to Vygotsky (1934/1987), by about age 7, personal speech is physically transformed into “inner speech”, which is a “silent” form of speaking that is inaudible to others. In inner speech, a person “speaks” and “hears” words internally. With the ability to think dialogically and conversationally inside one’s own head, a developing preadolescent is now equipped to re-engage interpersonal conversations at a new level of understanding and skill. He or she can speak intelligently during a speaking turn by engaging in inner speech “thinking” and “planning” during the preceding listening turn. This brings the developmental process full circle. It should be noted that development is not complete for most of us at age 12, for there is much in our vocabularies and in our understanding that never reaches its developmental potential. While mastery of the process of learning one’s native language is essentially complete by about age 12, it could take more than a lifetime to complete the process of applying one’s mastery to all of the verbal and non-verbal material that a person experiences. 51. One other feature to consider before we wrap up this segment is the correspondence between the stages of thinking and speaking in particular and the stages of the dialectical or developmental process in general—as originally conceived by the philosopher Frederick Hegel (1874). There are two stages that anchor development—the initial stage and the final stage. Between them is the stage of negation or inversion, in which one of the conflicting opposites asserts its dominance. This change in dominance from Stage A to Stage B draws out new qualities but also leads to new obstacles. The process moves forward when Stage B is negated by Stage A, resulting in a state of affairs in which the key properties of Stage B are incorporated into Stage A. In this case, social speech dialogues based on an unanalyzed and implicit understanding of dialogue are first transformed into a means for producing analyzed and explicit understanding. Then this new verbal form of explicit thinking is structurally transformed into an abbreviated and silent form of explicit thinking. Finally, there is a return to social speech dialogues, only this time the developing adolescent has inner speech as a tool. With inner speech, naïve social speech can be augmented and transformed into intelligent, rational social speech. The pattern, incidentally, is A-B, B-A. 52. 2) Why Private Speech is Necessary for Children Who Are Learning to Think Dialogically 53. Let’s briefly return to our model of “speaking and thinking” based on the notion of “psychological subject” and “psychological predicate”. Notice that the movement from speaking to listening is a cooperative and public activity in which the participants are each assigned a reciprocal or complementary task—the speaker regards the utterance as a psychological predicate, whereas the listener regards the same utterance as a psychological subject. The speaker “utters words”, while the listener “comprehends meanings”. But the movement from listening to speaking crosses a bridge which links the next utterance to the last one. The new utterance must constitute a culturally appropriate response to the prior one. Fortunately, the division of labor in a dialogue is constructed in such a way that the movement from listening to speaking is conducted entirely within the consciousness of a single individual. 9 54. We can illustrate this simply by shifting our box over. By means of interpersonal speech, a developing child has an intimate involvement in directing the movement from listening to speaking. But according to Piaget and Inhelder (1963/1977), in order for children (or adults) to comprehend the logic of a psychological system, they must understand how to reverse their movements within it. In the case of a dialogical system such as conversation, this would mean having an intimate involvement in the movement from speaking to listening as well. In what circumstances can a single person experience the same utterance from the perspective of the speaker as well as that of the listener? 55. The answer is: private speech activity. During play time, young children tend to retreat from social speech in order to take advantage of the many personal uses of private speech. Besides expressing emotions, noting difficulties, and describing and conducting imaginary play, they can also experience both sides of a conversation. In private speech, children can get intimately involved in the activity of listening to themselves speak. 56. 3) Special Considerations in Applying Conversational-Act Analysis to Private Speech 57. In social speech conversations, speakers alternate turns at talk. Each person produces a single speech utterance per turn. A speech utterance can be as short as a single word or as long as a political address. Each person's utterance is interleaved with the utterances of the other person. Consequently, it is easy to identify the start and end of any single utterance—it is bounded before and after by the other person's utterances. Private speech presents a particular challenge to identifying the start and end of any single utterance, however, because there is only one speaker. While breath pauses of two seconds or longer, combined with information about grammatical structure and intonational contour, typically indicate the start and end of utterances that are sentence-length or shorter, additional information is needed in order to determine if an utterance is actually a monologue, consisting of many sentences. The additional information that is needed concerns the relationship between private speech and the role it plays in some practical activity. Imagine a stream of individual sentences, each of which relates to some different aspect of an ongoing activity. These otherwise unrelated sentences could actually be part of a single speech utterance simply by virtue of their being related to the same goal with respect to the activity. 58. 4) Development of the Relationship Between Private Speech Activity and Practical Activity 59. In my opinion, the most fascinating problem in Vygotsky’s (1934/1987) theory is the developmental transition that occurs in the relationship between private speech and practical activity. This change occurs approximately when a child is between five and seven years of age. Vygotsky described this transition with an anecdote about a child drawing a picture. At the beginning of the activity, the boy used his private speech to comment on his drawing after the fact. Later, he remarked aloud to himself as an accompaniment to his activity. Then, when his pencil broke, he uttered the word “broken”, and then proceeded to alter his activity by drawing a wagon with a broken wheel. The development of conscious awareness in children may very well be rooted right here—in their awareness and understanding of the cognitive uses of private speech, which soon becomes reformulated as inner speech. But thinking develops hand-in-hand with speaking, so we should also be investigating the 10 development of conversational exchanges in private speech. After all, with the help of adults, children are able to speak dialogically long before they acquire the ability to think dialogically. 60. It should come as no surprise that question-answer exchanges play an important role in the development of children’s understanding and use of private speech. Here is the system devised by Lawrence Kohlberg and his associates (1968) to classify the developmental stages of private speech. According to Vygotsky (1934/1987), children start out using private speech involuntarily—to play with words, to release emotion, and to fantasize. But with development, they begin using private speech as a means for reflecting mentally, and for guiding and planning their behavior. 61. In Kohlberg et al.’s (1968) system, this turning point is signaled by a new form of private speech: “Questions answered by the self”! What could be more indicative of a child who has mastered an understanding of the perspective-taking character of dialogue than his performing both turns in a conversational exchange? 62. 5) An Example of the Application of Conversational-Act Analysis to Private Speech Data 63. Background: A Private Speech Monologue [Show PS Episode 1 uninterrupted (full-screen)] [Show PS Episode 1 uninterrupted (minimize screen) – With Transcript in Excel] [Show Re-Structuring of Transcript to Capture Monologues – in Excel] [Show PS Episode 1 in stop-action (minimize screen) – With C-Act Codes in Excel] 64. 6) A Participatory Exercise--Applying Conversational-Act Analysis to Private Speech Data [Show Remaining PS Episode 1 uninterrupted (minimize screen) – With Transcript in Excel] [Show Remaining PS Episode 1 in stop-action (minimize screen) – With C-Act Codes in Excel] 65. End of Part 2 References Akhutina, T.V. (2003). The role of inner speech in the construction of an utterance. Journal of Russian and East European Psychology, 41(3/4), 49-74. Austin, J. L. (1962). How to do things with words. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bakhtin, M.M. (1981). The dialogical imagination. (M. Silverstein, Trans.). Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. San Francisco: Chandler. Dore, J. (1977). "Oh them sheriff": a pragmatic analysis of children's responses to questions. In S. Ervin-Tripp & C. Mitchell-Kernan (Eds.), Child discourse (pp. 139-163). New York: Academic Press. 11 Dore, J. (1979). Conversational acts and the acquisition of language. In E. Ochs & B.B. Shieffelin (Eds.), Developmental pragmatics (pp. 339-361). New York: Academic Press. Garvey, C. (1975). Requests and responses in children’s speech. Journal of Child Language, 2, 41-63. Halliday, M.A.K. (1970). Language structure and language function. In J. Lyons (Ed.), New horizons in linguistics (pp. 140-165). Harmondsworth, England: Penguin. Hegel, G. W. F. (1874). The Logic. Encyclopaedia of the Philosophical Sciences. 2nd Edition. London: Oxford University Press. Katz, J. J. (1972). Semantic theory. New York: Harper and Row. Kohlberg, L., Yaeger, J., & Hjertholm, E. (1968). Private speech: Four studies and a review of theories. Child Development, 39(3), 691-736. Lewis, D. (1972). General semantics. In I.D. Davidson & G. Harman (Eds.), Semantics of natural language. Dordrecht, Holland: Reidel. Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1977). Intellectual operations and their development. In H.E. Gruber & J.J. Vonèche (Eds.), The essential Piaget: An interpretive reference and guide. (pp. 342-358). New York: Basic Books, Inc., Publishers. (Original work published 1963) Reber, A.S. (1989). Implicit learning and tacit knowledge. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 118, 219-235. Searle, J. R. (1976). A classification of illocutionary acts. Language in Society 5(1), 1-23. Vygotsky, L. S. (1962). Thought and language. (E. Hanfmann & G. Vakar, Eds. and Trans.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. (Original work published 1934) Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher mental processes. (M. Cole, V. JohnSteiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (Original work published 1930, 1933, and 1935) Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). Thinking and speech. In The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky: Volume 1. Problems of general psychology (pp. 39-285). (R. W. Rieber & A. S. Carton, Eds., N. Minick, Trans.). New York: Plenum Press. (Original work published 1934) 12