Creative Digitization

advertisement

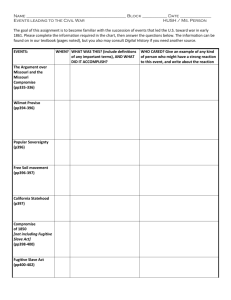

Wiring the Past: The Lincoln Telegrams Project The past is so often unknowable not because it is befogged now but because it was befogged then, too, back when it was still the present. If we had been there listening, we still might not have been able to determine exactly what Stanton said. All we know for sure is that everyone was weeping, and the room was full. Adam Gopnik, 2008, p. 142 John Lee North Carolina State University USA john_lee@ncsu.edu Philip Molebash Loyola Marymount University USA philip.molebash@lmu.edu Work in history requires analysis, inference, and ultimately trying to know the unknowable. Adam Gopnik reminds us how hard it is to know the past, in this case to know Edwin Stanton’s words at the deathbed of Abraham Lincoln. Did Stanton actually say, “Now he belongs to the ages?” We’ll never know, but we do know that learning history requires collaborative engagement in dynamic environments, with teachers and students working together to know the past. Such work is exciting, yet as educators we are often restrained in our efforts. Far too often, learning in history is reduced to students listening or memorizing without understanding how events connect. Teachers complain that their curricula are restrictive and materials are inaccessible. The weight of high stakes tests and the burden of content coverage conspire to put history teachers on the defense. A way out of this predicament is to use emerging technologies to encourage new ways to learn history. Wiring the Past: The Lincoln Telegrams Project has been designed to reimagine history education as a creative disciplinary experience supported through online communities and public work. The project focuses on the creative digitization and presentation of telegram memos written by and to President Abraham Lincoln and related analysis of these historical documents in online environments. The project seeks to promote a vision of history education that is amplified using technology in support of of teachers and students working to improve their disciplinary skills and their knowledge of the Lincoln presidency. Digital history is an emerging construct that describes processes for historians and students of history to develop dispositions, skills and content knowledge in the discipline of history. It includes new processes for providing access to historical materials, conducting historical inquiry, and presenting the results of historical research. Much like the emerging social history of several decades ago, digital history today offers something decidedly new. Beyond the additive value of online digital historical resources, digital history offers a new way of thinking about, doing, and communicating about history. Thomas (Interchange, 2008) describes these conditions in his working definition of digital history. On one level, digital history is an open arena of scholarly production and communication, encompassing the development of new course materials and scholarly data collections. On another, it is a methodological approach framed by the hypertextual power of these technologies to make, define, query, and annotate associations in the human record of the past. (Interchange, 2008, p. 454). Scholars, researchers, teachers, and students in the history today have access to a remarkable range of previously inaccessible resources (Cohen & Rosenzweig, 2005). The wide availability of digital historical resources has expanded opportunities for conducting historical research, and democratized the research process (Ayers, 1999; Rosenzweig, 2003). Beyond being able access historical resources, the Web now enables users to create, analyze, interpret, and communicate about historical ideas and issues. Fueling these new uses are collaborative technologies commonly termed Web 2.0 that enable not just information sharing but collaborative content generation using a wide range of continually evolving, primarily web-based tools (Boggs, 2007). Cohen (2004) has argued that the discipline of history is primed to move into the world of Web 2.0, which he describes as the “interaction between historians and their subjects, interoperation of dispersed historical archives, and the analysis of online resources using computational methods” (p. 293). In the few years since Cohen’s premonition, the field of history has indeed gone 2.0. Work in digital history is still a frontier populated by creative and experimental projects and a sense of shared passion by many who conducted research in the area. Digital history offers a laboratory for ideas and experimentation. New networks are emerging to support a wide range of people who are interested in learning about the past, and instructional resources are being developed that provide teachers and students guidance for using digital historical materials. However, digital history projects often lack pedagogical scaffolding and structure for use in k-12 and even college classrooms. Well-designed pedagogical interfaces can enhance the usability of existing digital historical resources for students. Pedagogical interfaces based on specific or practical pedagogical principles can serve to ease young learners into using digital historical materials in ways that support their developmental needs. Wiring the Past: The Lincoln Telegram Project aims to reimagine history education by focusing on four core questions. 1. What methods and tools can we use to creatively digitize and present historical resources for use in k-12 and college classrooms? (Creative Digitization) 2. How best can we provide purposeful access to digital historical resources so students can use the resources to conduct research? (Purposeful Access) 3. How can we use multimedia and disciplinary tools to support students as they conduct historical research? (Multimedia and Disciplinary Tools) 4. How can we use online social networks to expand publication, sharing and collaboration related to students’ historical research? (Social Networks) Creative Digitization Creative digitization involves imaginative and novel methods for presenting historical resources online. It is prompted by inquiry, or some desire to study the past, and facilitate using technology. By creatively digitizing historical resources, we can provide students access to unique historical collections in environments that are designed to meet instructional goals. Creative digitization merges process and product by encouraging educators to think about how they can represent digital sources used for historical inquiry. This project features the creative digitization of telegram memos written by and to President Abraham Lincoln. The digitization of this collection is unique and important in that the telegram memos represented a new form of communication and the content is focused on a central topic in United States history. Work on this project involves the creative digitization of microfilm from the National Archives and Records Administration for presentation on the Web given specific student user needs. Purposeful Access Purposeful access to digital historical resources suggests a range of uses. Depending on these, digital history sites can be either archival or interpretative. Archival sites attempt to recreate the structure of a collection as it existed when the materials where created or when the materials were collected. Interpretative historical websites present historical materials to reflect interpretations about the past. Wiring the Past: The Lincoln Telegrams Project aims to do a bit of each – archival and interpretative. Toward this goal, the following design principles are guiding this project. Principle 1 – Organizational constructs, metaphors, symbols, images, visual aids, and textual scaffolds should frame interpretations on digital history websites Principle 2 - Resources on digital history websites should be nonlinear, malleable, well focused, and pertinent to the interpretation Principle 3 - Digital history websites should invite active engagement and constructive interpretation Relative to the first principle, we present the telegrams on the same day they were written years later. For example, a telegram memo written on March 12, 1864 would be presented on March 12, 2012. This construct serves to invite users to imagine historical events on the day they occurred. The second design feature focuses on user interaction with the collection. We are working to develop an interface for the telegram collection that can be customized by users so that the collection can be accessed according to topical themes and areas of interest. Our third design feature includes elements that invite research and scholarly engagement with the resources. Multimedia and Disciplinary Tools Multimedia and disciplinary tools can support the use of digital historical resources. Multimedia enables students to engage resources in different modes and supports students as they construct products of their learning. Multimedia tools might enable the visual presentation of information, visualizations of data, the development of multimodal text, and the creation of audio and video products. Disciplinary tools include structures and ways of thinking in history that support purposeful inquiry. In education, disciplinary structures take form as cognitive scaffolds that support novice learners as they engage new content. Wiring the Past: The Lincoln Telegrams Project features the SCIM-C model (Hicks, Doolittle, & Ewing, 2004). SCIM-C was developed as a cognitive scaffold to help students develop the knowledge and skills necessary to interpret historical sources while conducting historical inquiry. The SCIM-C strategy includes five overarching phases: Summarizing, Contextualizing, Inferring, Monitoring, and Corroborating. An existing SCIM-C multimedia tutorial (http://historicalinquiry.com) includes three phases, explanation of the SCIM-C process, demonstration of the SCIM-C process, and participation in the SCIM-C process. Online Social Networks All digital historical resources have social context. Such context takes into consideration how and why we inquiry about the past. Online social networks extend collaboration and expand students’ opportunities to learn from one another and from experts. In these online environments, students are able to engage digital historical resources in ways that meet their needs, when their interests are piqued. High-quality online social networks support teachers and students who are inquiring about history while acting in the present on issues students and their teachers deem important. In this project, we are using collaborative authoring tools such as blogs and wikis to enable students to share work and learn from each other. Wiring the Past: The Lincoln Telegrams Project is designed to address an emerging gap between what is possible given the availability of innovative new web-based resources and the reality of k-12 and college history education. The central issue for this project is not the quantity of the focus on technology and history, but rather the quality of that focus. It is essential that the digital historical resources developed in this project be built upon pedagogical principles that prepare students and teachers to work in networked classrooms so that resources can be used (a) as tools for inquiry; (b) to create authenticity in the doing of history, which facilitates the process of student inquiry and action; (c) and to cultivate students’ academic interests by using technology to foster autonomous, creative and intellectual thinking. References Ayers, E. L. (1999). The pasts and futures of digital history. Retrieved February 20, 2009, from http://jefferson.village.virginia.edu/vcdh/PastsFutures.html. Boggs, J. (2007). Web 2.0 for historians: An introduction. Journal of the Association for History and Computing, 10(2). Retrieved September 20, 2007, from http://mcel.pacificu.edu/jahc/jahcx2/boggs.html Cohen (2004). History and the second decade of the Web. Rethinking History, 8(2), 293-301. Cohen, D. & Rosensweig, R. (2005). Doing digital history: A guide to presenting, preserving, and gathering the past on the Web. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Gopnik, A. (2009). Angles and ages: A short book about Darwin, Lincoln, and modern life. New York: Random House. Hicks, D., Doolittle, P. E., & Ewing, T. (2004). The SCIM-C strategy: Fostering historical inquiry in a multimedia environment. Social Education, 68(3), 221-225. Interchange: The promise of digital history. (2008). Journal of American History, 95(2), 452-491. Rosenzweig, R. (2003). Scarcity or abundance? Preserving the past in a digital era. American Historical Review, 108 (3), 735–62.