House of the Seven Gables - Khazar Journal of Humanities and

advertisement

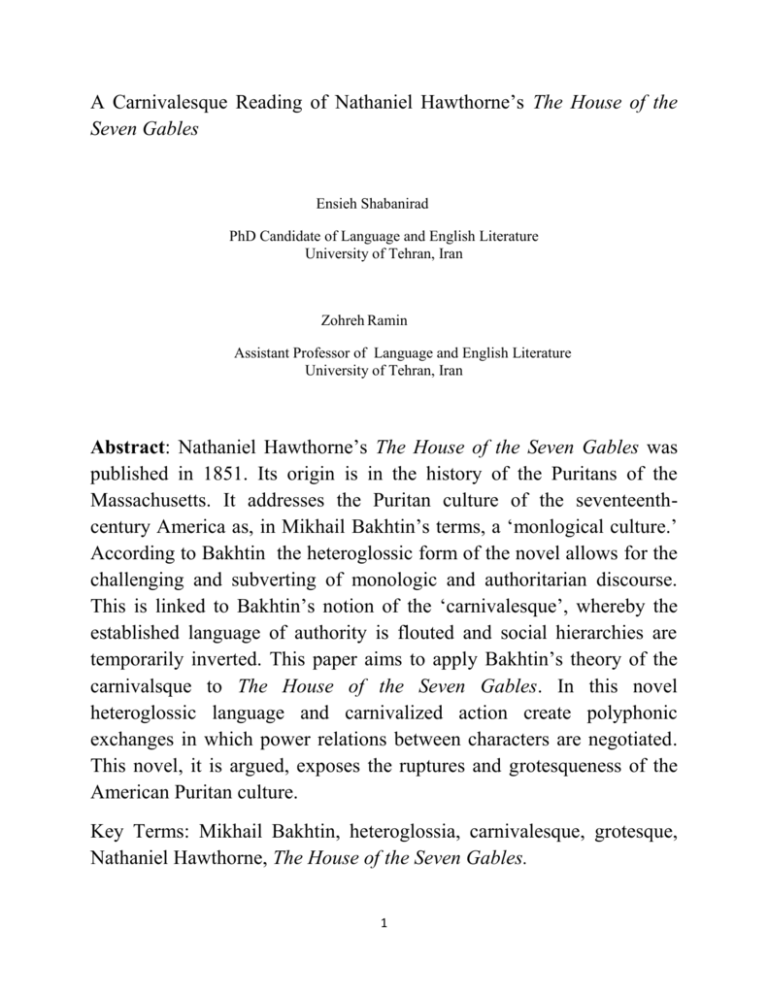

A Carnivalesque Reading of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables Ensieh Shabanirad PhD Candidate of Language and English Literature University of Tehran, Iran Zohreh Ramin Assistant Professor of Language and English Literature University of Tehran, Iran Abstract: Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables was published in 1851. Its origin is in the history of the Puritans of the Massachusetts. It addresses the Puritan culture of the seventeenthcentury America as, in Mikhail Bakhtin’s terms, a ‘monlogical culture.’ According to Bakhtin the heteroglossic form of the novel allows for the challenging and subverting of monologic and authoritarian discourse. This is linked to Bakhtin’s notion of the ‘carnivalesque’, whereby the established language of authority is flouted and social hierarchies are temporarily inverted. This paper aims to apply Bakhtin’s theory of the carnivalsque to The House of the Seven Gables. In this novel heteroglossic language and carnivalized action create polyphonic exchanges in which power relations between characters are negotiated. This novel, it is argued, exposes the ruptures and grotesqueness of the American Puritan culture. Key Terms: Mikhail Bakhtin, heteroglossia, carnivalesque, grotesque, Nathaniel Hawthorne, The House of the Seven Gables. 1 1. Introduction: Bakhtin and Carnival Mikhail Bakhtin, the Russian thinker, is one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century. He has made great contributions in such fields as history, philosophy, sociology, psychology, linguistics and literature. Writing under the repressive Soviet regime of Joseph Stalin, Bakhtin labored most of his life in obscurity. In David Lodge’s words, Bakhtin’s career was “an extraordinary story of outstanding intellectual achievement in the teeth of every imaginable obstacle and discouragement” (3). Bakhtinian concepts such as dialogism, polyphony, heteroglossia and carnival, to name just a few, have dominated Western literary theory and criticism towards the end of the twentieth century. Bakhtin’s theory of the novel relies on the key concept of the carnivalesque which was first introduced in his well-known book Rabelais and His World, a study of the writings of Francois Rabelais (1494-1553). The novel is the form, as Simon Dentith explains, “which most exploits the heteroglossic potential that is present in all languages that come from all but the most isolated and homogenous societies. But the specific social and institutional form which enables and anticipates the activity of the novel is the epochal force of carnival” (Simon Dentith 57). Carnival is a subversive force, a lived experience, providing an opportunity for the people to oppose the authority. In fact, carnival allows people who in life are separated by hierarchical barriers to enter into free and tangible contact, suspending the established official order and allowing new relationships to emerge. Carnival turns the world upside down. Hierarchies are reversed and suspended. As Vincent B. Leitch points out, “The carnivalesque is Bakhtin’s term for those forms of unofficial culture that resist official culture, political oppression, and totalitarian order through laughter, parody, and grotesque.” (1187) In relation to Rabelais, Bakhtin shows how the official ceremonies and customs of the Church and the feudal state are parodied and ridiculed by rituals that show low bodily functions. Some critics interpret Bakhtin’s account of carnival as being a critique of Stalinism. Bakhtin’s study of Rabelais, in Dominick LaCapra’s words, “can be read as a hidden 2 polemic directed against Stalinist uses of Marxism in the Soviet regime of the 1930s and 1940s” (321). Bakhtin’s conception of carnival creates a fulfilling and intellectually acceptable vision of an “alternative social context” to the Stalinist system(Ibid. 322). Carnival opposes all that is Stalinist: the dialogical voice of unofficial culture in the people resisted the theological monologism of the Catholic Church and tyrannical communism; the grotesque body was celebrated, not condemned as sinful; collective laughter in broad daylight defeats eschatological terror and laughter as sinful in Russia; vitalist primitivism replaces the ascetic and life-denying culture of celibate prelacy. The utopian freedom of permanent becoming transcends the prison house of dogma and Gulag of dissent. (Shakespeare and Carnival: 4) Carnival practices are found throughout the world. Carnival was traditionally staged as a licensed or authorized activity, not only offering an alternative to official imagery but also suspending and inverting social hierarchies. It provided an alternative construction of social relations. For Bakhtin, carnival is both a populist utopian vision of the world seen from below and a festive critique, through the inversion of hierarchy, of the ‘high’ culture: As opposed to the official feast, one might say that carnival celebrates temporary liberation from the prevailing truth of the established order; it marks the suspension of all hierarchal rank, privileges, norms, and prohibitions. Carnival was the true feast of time, the feast of becoming, change and renewal. It was hostile to all that was immortalized and complete. (Bakhtin 1968: 109) Carnival is presented by Bakhtin as a world of topsy-turvy, of heteroglot exuberance, of ceaseless overrunning and excess where all is mixed, hybrid, ritually degraded and defiled. Carnivalesque practices, in general, consist of three key aspects: grotesque imagery, laughter, and the market location. 3 1.1. Grotesque imagery Carnivalesque practices were imbued with images of the grotesque body, images of “exaggeration, hyperbolism…[and] excessiveness” (Bakhtin Rabelais: 303). Fundamental to the corporeal, collective nature of carnival is what Bakhtin calls ‘grotesque realism’. It emphasizes the material and the bodily. Grotesque realism uses the material body to represent cosmic, social, and linguistic elements of the world. In contrast with the classic conception of the body as a complete, individual entity, the grotesque conception of the body was of an incomplete, amorphous entity. Moreover, grotesque imagery contributed to the alternative construction of reality provided by carnival as a whole. The material imagery of the grotesque not only provided an alternative to the spiritual imagery of the Church, but the dynamism of the grotesque body represented an alternative to the stasis of the official order. This is because, as Peter Stallybrass points out, “it is always in process, it is always becoming, it is a mobile and hybrid creature, disproportionate, exorbitant, outgrowing all limits, obscenely decentered and off-balanced, a figural and symbolic resource of parodic exaggeration and inversion” (9). Therefore, the grotesque imagery represents an alternative to the symbolism and ideology of officialdom. While official culture always strove to portray social relations as natural and unchanging, grotesque imagery contrastingly represented the extent to which human existence was bound up with processes of transition. ‘The essential principle of grotesque realism’, Bakhtin writes, ‘is degradation’ (Rabelais, 19). In carnival the high, the elevated, the official, even the sacred, is degraded and debased, but as a condition of popular renewal and regeneration. Carnival always celebrates renewal. 4 1.2. Laughter Grotesque imagery also has an important connection with laughter, the second aspect of carnival. Bakhtin ascribes great importance to the spirit of carnivalesque laughter. Let us say a few initial words about the complex nature of carnivalesque laughter. It is, first of all, a festive laughter. Therefore it is not an individual reaction to some isolated ‘comic’ event. Carnival laughter is the laughter of all the people. Second, it is universal in scope; it is directed at all and everyone, including the carnival’s participants. The entire world is seen in its droll aspect, in its gay relativity. Third, this laughter is ambivalent: it is gay, triumphant, and at the same time mocking, deriding. It asserts and denies, it buries and revives. Such is the laughter of the carnival. (Bakhtin 1968: 11-12) Carnival laughter has a vulgar, earthy quality to it. It was responsible for shaking the body out of its proper form; laughter caused an eruption of the other within the self, and it was probably for such a reason ─ the transgression of bodily propriety, that Bakhtin places particular emphasis on laughter. Laughter was also transgressive because it traversed the limits of all social forms and was very ambiguous. While it humiliated and mortified, it also revived and renewed. “Laughter degrades and materialises” (Bakhtin 1968: 20). In carnival, laughter pushes aside the seriousness and hierarchies of official life. Carnival laughter is egalitarian, and derision, not death, is the great leveller. In his essay ‘Epic and Novel’, Bakhtin accredits laughter with the capacity to undertake a thorough examination of objects that fall within its scope: 5 Laughter has the remarkable power of making an object come up close, of drawing it into a zone of crude contact where one can finger it familiarly on all sides, turn it upside down, inside out, peer at it from above and below, break open its external shell, look into its center, doubt it, take it apart, dismember it, lay it bare and expose it, examine it freely and experiment with it. (Bakhtin The Dialogic Imagination: 23) According to Bakhtin, carnivalesque laughter had the potential to demystify reality insofar as it provided the means for probing the objects around it. It was not the objects of laughter, though, that interested Bakhtin so much as the perspective laughter brings. Laughter drew attention to the forms of relationship which were often fixed in one-sided, hierarchical order. Carnival laughter could subvert official authority. Through laughter, according to Bakhtin, “the world is seen anew, no less (and perhaps more) profoundly than when seen from the serious standpoint…Certain essential aspects of the world are accessible only to laughter” (1968: 66) 1. 3. The marketplace The third aspect of carnival is its typical location: the marketplace. Bakhtin locates the autonomy of the people in the marketplace where grotesquery and laughter took place. To Bakhtin the marketplace was an unofficial site where people were in control, a place where people could experience a sense of their own collectivity: The carnivalesque crowd in the marketplace or in the streets is not merely a crowd. It is a people as a whole, but organized in their own way, the way of the people. It is outside of and contrary to all existing forms of the coercive socioeconomic and political organization, which is suspended for the time of the festivity. (Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World 255) 6 Here in the market place people could communicate freely and frankly. The coarse and familiar speech of the fair and the marketplace provided a complex vital repertoire of speech patterns excluded from official discourse which could be used for parody, subversive humor and inversion. In the fair, the place of high and low, inside and outside, stranger and local, commerce and festivity was never a simple given. In such a hybrid place , Bakhtin argued, one could experience “a certain extraterritoriality” from “official order and official ideology” (154): Abuses, curses, profanities, and improprieties are the unofficial elements of speech…Such speech forms, liberated from norms, hierarchies, and prohibitions of established idiom, become themselves a peculiar argot and create a special collectivity.( Bakhtin 1968: 187) The language of the marketplace is ambivalent and subversive, simultaneously debasing and renewing, revealing and hiding, selling and entertaining. Therefore, while carnival laughter and grotesquery had the potential to critique the ruling ideology, it was in the marketplace that people could voice the suppressed and the unexpressed. 2. Carnival and The House of the Seven Gables Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables was published in 1851. Like its predecessor, The Scarlet Letter, its origin is in the history of the Puritans of the Massachusetts. Hawthorne’s family history can be traced in this later book as well, in the story of the Pyncheon family over two hundred years in Salem. Puritanism and the history of early Massachusetts settlements form one important context in which to understand Hawthorne’s writing. Scholars such as Charles Ryskamp and Michael Colacurcio have connected characters and events in Hawthorne’s works to the New England historical record. A tale of the effects of sin and guilt as manifested through successive generations of a New England family, Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables is a novel with multiple levels of meaning that have lead to a wide variety of 7 critical interpretations. The events of The House of the Seven Gables center on the Pynchon House, located on a piece of land obtained more than a hundred-fifty years earlier by Colonel Pyncheon after he had played a role in having the land’s owner, Mathew Maule, hanged as a wizard. According to legend, Maule placed a curse on the Colonel. This curse became the source of many misfortunes suffered by his descendants. Bakhtin’s notion of carnival appears germane to the novels of Nathaniel Hawthorne. A carnivalesque reading of The House of the Seven Gables uncovers the subversive elements in the American Puritan culture and highlights the cultural exchange between the forces of gentility and democracy. The language of heteroglossia is evident in this tale, giving voice to a variety of discourses explaining the world of New England. These discourses include the language of New England Puritanism obsessed by sin and determination, the language of capitalism and commerce, describing a world dominated by profit and loss, and the language of science and technology. Each discourse Hawthorne employs in this novel creates a different way of understanding the transitional world of the new world. Throughout his novel The House of the Seven Gables Hawthorne brings together heterogeneous collections of characters from various social orders and have them mingle in festival-like gatherings reminiscent of medieval carnival celebration. For another, the interaction among these disparate characters often results in the suspension of hierarchical barriers and in what Bakhtin calls “carnivalistic mésalliances” that mingle “the sacred with the profane, the lofty with the low, the great with the insignificant, the wise with the stupid” (Problems 123). As Bakhtin argues, All distance between people is suspended, and a special carnival category goes into effect: free and familiar contact among people. This is a very important aspect of a carnival sense of the world. People who in life are separated by impenetrable hierarchical barriers enter into free familiar contact on the carnival square. (123) 8 Thus, familiar and free format of carnival allows everything that may normally be separated to reunite. More than any other of Hawthorne’s novels, The House of the Seven Gables seems attuned to the American present – engaged with various social, economic, and technological phenomena. It also features class conflicts, business and political intrigue.(Person) In Harold Bloom’s words: “This novel portrays Hawthorne’s contemporary world more than his other American novels…the contemporary, the local, and the national qualities lurk between the lines… Nevertheless, this novel contains the most “literal actuality” in any of Hawthorne’s novels”. (Harold Bloom) The House of the Seven Gables constitutes Hawthorne’s employment of American philosophy as a basis for a social ethic. The theme of this romance is an inherited sin, the sin of aristocratic pretensions against a moral order which calls for a truer evaluations of man. For the inheritance of the Pyncheon family proves to be no more than the antagonism of the old Colonel and his world toward things democratic. Hawthorne was aware of the fact that the Puritan society of New England had been as aristocratic in its way as the feudal society of Europe. He saw the sharp contrast that existed between the various members of the social group. The servants who stood inside the entrance to the House of the Seven Gables directing one class of people to the parlor and the other to the kitchen preside likewise over the social distinctions of the whole story, separating the Pyncheons from the Maules and gentility from democracy. Standing as the division between high and low, the house is located midway between two civilizations. It faces the commerce of the street on the west, while to the rear is an old garden. To move from the sepulchral darkness of the old Pyncheon house to the dusky sunlight of the street is to discover the hubbub of the contemporary environment. The locus of the carnival is the street where counter-hegemonic, subversive and mocking voices run parallel to the official, serious, and pious tone of the ruling class. Although Hawthorne occasionally describes the street as a quiet by-way, he obviously intended to capture within it the whole throbbing turmoil of nineteenthcentury life in this country. The street becomes "a mighty river of life, 9 massive in its tide," brimming with chattering housewives and raucous peddlers and venders; the world is like a train or a bus dropping, here and there, a passenger, and picking up another. It seems that the town’s streets are bustling with life. As the story opens, Hepzibah Pyncheon, the inhabitant of the gabled house, is compelled at the age of sixty to stoop from her aristocratic isolation from the world , and open a little shop, in order that she may provide for the subsistence of an unfortunate brother. The chapters entitled “The Little Shop-Windoew,” “The First Customer,” and a “Day Behind the Counter,” in which her humiliations are described, include the mingling of the high and the low and the inversion of the hierarchies. Hepzibah Pyncheon’s reluctant decision to open a cent shop because she desperately needs the money enables Hawthorne to engage the streets of Salem – to represent the street traffic that otherwise would never enter the aristocratic precincts of the House. Hepzibah feels embarrassed when she discovers that her customers “evidently considered themselves not merely her equals, but her patrons and superiors” (2: 54). After her first day on the job, this “decayed gentlewoman” (2: 54) comes to some “disagreeable conclusions as to the temper and manners of what she termed the lower classes, whom, heretofore, she had looked down upon with a gentle and pitying complacence, as herself occupying a sphere of unquestionable superiority.” One of Hawthorne’s purposes is to portray the social leveling forces at work in American society, coincident with the rise of business, manufacturing, and a host of opportunities to sell things, including entertainment, to increasingly wealthy middle-class people. Hepzibah, for example, quickly finds herself with a double identification. Suddenly a member of the shopkeeper’s class, she looks with disdain at the “idle aristocracy” – at one woman in particular, whose “delicate and costly summer garb” and “slippered feet” make her look as if she is floating down the street. “For what good end,” Hepzibah wonders bitterly, “in the wisdom of Providence, does that woman live! Must the whole world toil, that the palms of her hands may be kept white and delicate?” (2: 55). Even if the central focus of the novel remains the fortunes of the aristocratic Pyncheons, Hawthorne includes a working-class perspective 10 – often in the form of characters who critique the Pyncheons from outside their house. Even before Hepzibah has her first customer, two “laboring men” assess her prospects (2: 47). Savvy patrons of local businesses, they don’t think much of Hepzibah’s chances. Jaffrey will later tell her that, ever since Clifford’s return from prison, her “neighbors have been eye-witnesses to whatever passed in the garden. The butcher, the baker, the fishmonger, some of the customers of your shop, and many a prying old woman, have told me several of the secrets of your interior” (2: 236). This remarkable statement, which sounds more like something we would hear in our own time, is a function of social leveling. The street itself is a marketplace, furthermore, featuring vendors and popular entertainers. In his introductory chapter Bakhtin outlines the basis of his approach to what he sees as Rabelais’ ‘world’. There are two principal concepts, that of carnival and the grotesque. Bakhtin conceives an oppositional folk culture the expression of which is humour: All these forms of protocol and ritual based on laughter and consecrated by tradition existed in all the countries of medieval Europe; they were sharply distinct from the serious, official, ecclesiastical, feudal and political cult forms and ceremonials. They offered a completely different, non-official, extra-ecclesiastical and extra-political aspect of the world, of man, and of human relations; they built a second world in which all medieval people participated more or less, in which they lived during a given time of the year. (pp. 5–6) In a scene that Hawthorne took directly from his notebook, he describes an organ grinder and his monkey, who set up opposite the Pyncheon house to entertain the crowd. With his “man-like expression” and “enormous tail, (too enormous to be decently concealed under his gabardine” (2: 164), the organ grinder’s monkey creates a scene imbued with the spirit of carnival. Representative of increasingly popular forms of mass entertainment, such as the minstrel show, the monkey “offers the sort of obscene caricature of black male sexuality so common within the period’s minstrel performances” (Anthony, 447). The chapter (“The Arched Window”) in which the organ-grinder appears is a set piece – an 11 example of the crowd scenes that Hawthorne loved to write and an opportunity for him to root the House of the Seven Gables in the texture of popular culture. Class conflict plays an important role in The House of the Seven Gables in the tension between the Pyncheons and the Maules, and Holgrave clearly comes from a workingman’s background. “I was not born a gentleman,” he insists to Hepzibah; “neither have I lived like one” (2: 45). He is the sort of man Hawthorne encountered on the docks in Boston and Salem when he worked in the Custom Houses there, and he resembles many of the Brook Farmers whose ranks Hawthorne seemed proud to join. Holgrave promises to be a spokesman for democratization and social leveling of the sort that the Brook Farmers imagined. The terms “lady” and “gentleman,” he observes, “had a meaning, in the past history of the world, and conferred privileges, desirable, or otherwise, on those entitled to bear them. In the present – and still more in the future condition of society – they imply, not privilege, but restriction” (1: 45). A man on the make, Holgrave also represents the new breed of entrepreneurial opportunists that proliferated in nineteenth-century America. In stark contrast to Hepzibah, who feels as if the “sordid stain” from the first copper coin she receives in her newly opened cent shop “could never be washed away from her palm” (1: 51), Holgrave seems comfortable in a society that increasingly valued and rewarded men who invested themselves in business and marketable professions. Protean in his capabilities–a far cry from the eighteenth-century model of artisanship and lifelong devotion to a single craft–he is only twenty-two years old but has already held many positions: country schoolmaster, salesman, editor, peddler, dentist, mesmerist, and of course Daguerreotypist (2: 176). Holgrave has changed with the economy, taking up each new thing as it comes along and promises to turn a profit. Class issues in The House of the Seven Gables reflect a deep, fearful interest in class generally in the 1850s, a time of social crisis when, as Hawthorne himself experienced, bourgeois existence became dominant ideologically, yet remained highly vulnerable to economic uncertainty (Richard H. Millington 92). Women are a focal point in Hawthorne’s deconstruction of these class formations. In an economy where only 30 12 percent of women (mainly unmarried and seldom middle class) did paid work, middle-class women’s material dependency on male family members demonstrated their social ascendancy. But this also contained the threat of destitution and the loss of the fiercely promoted feminine “decency” that distinguished their middle-class existence in moral terms while veiling its actual financial base. So the event most likely to dismantle the bourgeois illusion is the woman going out to work, or in the case of House of the Seven Gables, the private home shockingly opened up to commerce when unsupported gentlewoman Hepzibah starts her shop. Historically, separation of money-making work premises from the home was fundamental in the new capitalist order; here the shop is tellingly part of the house. Several commentators have interpreted the novel as a statement of the superiority of American democracy to the Old World aristocratic social system. However, in the chapter “Behind the Counter” Hawthorne demonstrates how far American society is from the fundamental egalitarian principles. Hepzibah, at the opening of the book the sole possessor of the dark recesses of the mansion, is the embodiment of decayed gentility, sustained only by her delusion of family importance, lacking any revivifying touch with outward existence. It is impossible in the present state of society even for the dark old sanctuary of Pyncheon gentility to preserve its insularity intact. Let us behold, in poor Hepzibah, the immemorial, lady— two hundred years old, on this side of the water, and thrice as many on the other, —with her antique portraits, pedigrees, coats of arms, records and traditions, and her claim, as joint heiress, to that princely territory at the eastward, no longer a wilderness, but a populous fertility,—born, too, in Pyncheon Street, under the Pyncheon Elm, and in the Pyncheon House where she has spent all her days, — reduced. Now, in that very house, to be the hucksteress of a cent‐shop. (26) 13 The opening of the cent-shop to let the outside world into the stifling interior of the secluded house is a symbol of the salutary virtues of the Maule forces, or the forces of democracy, in contrast to the moribund condition of the Pyncheons. “ In this republican country, amid the fluctuating waves of our social life, somebody is always at the drowning‐point.”(26) The Pyncheons were drowning in their own separateness, unable to draw the breath of life because they had so entirely shut themselves away from it. The cent-shop is a kind of pulmonary connection from humanity to the almost strangled existence of the House of the Seven Gables: Hitherto, the life‐blood has been gradually chilling in your veins as you sat aloof, within your circle of gentility, while the rest of the world was fighting out its battle with one kind of necessity or another. Henceforth, you will at least have the sense of healthy and natural effort for a purpose, and of lending your strength be it great or small—to the united struggle of mankind. This is success,— all the success that anybody meets with!(31) Hepzibah’s first customer is an urchin, Ned Higgins, who is given a free gingerbread man and immediately comes back for another. He wants, in fact, to exploit an individual who out of generosity and out of aristocratic reluctance to go into trade ignores the laws of a free market economy and gives instead of barters. It is no accident, surely, that the gingerbread man is Jim Crow, the colloquial, demeaning name for blacks. The urchin unceremoniously swallows both Jim Crow gingerbread men. This is a comic but telling image of an oppressive caste and class society. The gingerbread incident leads Hepzibah to change her mind about the class system, and she comes “to very disagreeable conclusions as to the temper and manners of what she termed the lower classes, whom, heretofore, she had looked down upon with a gentle and pitying complacence, as herself occupying a sphere of unquestionable superiority.” At the same time she finds herself fiercely resentful of the 14 idle aristocracy to which she has herself recently belonged. Seeing an expensively dressed lady floating along the streets, she wonders: “Must the whole world toil, that the palms of her hands may be kept white and delicate?” Now in trade as well as desperately poor, she has a new, sour, view of the oppressive and discriminatory social system that keeps some idle while many toil and suffer. It takes some time, therefore, for her to realize the truth in Holgrave’s remark to her that in working for a living: “you will at least have the sense of healthy and natural effort for a purpose, and of lending your strength be it great or small to the united struggle of mankind. This is success,—all the success that anybody meets with!” Hepzibah did undergo “the invigorating breath of a fresh outward atmosphere, after the long torpor and monotonous seclusion of her life.”(36-37) But the experience was transitory. She retained her aristocratic arrogance, and inwardly despised the people by whose pennies she hoped to be sustained. The democracy she still repudiated failed to provide for her because she tried to take it in on her own conditions, to pervert it to her own undemocratic ends. Hepzibah, “the recluse of half a lifetime,” proved pathetically incapable of merging with humanity in the common struggle for existence. The childish, ineffectual Clifford exemplifies a maladjustment like his sister. But he too had moments in which he felt the regenerative urge to burst from the inner prison of himself into the stream of life. “With a shivering repugnance at the idea of personal contact with the world, a powerful impulse still seized on Clifford, whenever the rush and roar of the human tide grew strongly audible to him.” (126) On one such occasion he was watching from a window of the House of the Seven Gables when a political parade went by in the street below. It seemed “one broad mass of existence,—one great life,—one collected body of mankind, with a vast, homogeneous spirit animating it. But, on the other hand, if an impressible person, standing al one over the brink of one of these processions, should behold it, not in its atoms, but in its aggregate,—as a mighty river of life, massive in its tide, and black with mystery, and, out of its depths, 15 calling to the kindred depth within him.” (126-127) So strong was the influence on him to join in the march of his fellow men that it affected him as a sort of primal madness, and he could “hardly be restrained from plunging into the surging stream of human sympathies.” He was impelled, Hawthorne suggests, by “a natural magnetism, tending towards the great centre of humanity.” Breathlessly he remarked to the terrified Hepzibah that had he taken the plunge and survived it, it would have made him another man. Hawthorne interpolates again by saying that he “required to take a deep, deep plunge into the ocean of human life, and to sink down and be covered by its profoundness, and then to emerge, sobered, invigorated, restored to the world and to himself.”(127) In his desire shortly after this incident to join the villagers going to church on Sunday, he displayed a “similar yearning to renew the broken links of brotherhood with his kind.” Yet he and Hepzibah were unable to go through with it once they stood on the front step in plain sight of the whole town and all its citizens. They retreated into the gloom of the house which was the historical and material symbol of the isolation of their hearts, “For, what other dungeon is so dark as one’s own heart! What jailor so inexorable as one’s self!” The novel is making the point that unless we escape from the past and accept our common, democratic, yet independent lot, we remain shackled to it. 3.Conclusion Through the carnival and carnivalesque literature, a ‘world upsidedown’ is created, ideas and truths are endlessly tested and contested, and all demand equal dialogic status. The ‘jolly relativity’ of all things is proclaimed by alternative voices within the carnivalized literary text that de-privileged the authoritative voice of the hegemony through their mingling of high culture with the profane. For Bakhtin it is within literary forms like the novel that one finds the site of resistance to authority and the place where cultural, and potentially political, change can take place. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The House of the Seven Gables has its origin in the Puritan culture of the seventeenth-century America which is considered, in Bakhtin’s terms, a ‘monlogical culture.’ 16 According to Bakhtin the heteroglossic form of the novel allows for the challenging and subverting of monologic and authoritarian discourse. In this novel heteroglossic language and carnivalized action create polyphonic exchanges in which power relations between characters are negotiated. This novel exposes the ruptures and grotesqueness of the American Puritan culture. The Salem street and the marketplace in The House of the Seven Gables are public domains where diverse economic, gender, and ethnic groups are present. It is the site of carnival, a place in which the ruptures and grotesqueness of the American Puritan culture is exposed and people are seen as equals. 17 Works Cited Bakhtin, Mikhail. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Ed. and trans. Caryl Emerson. Theory and History of Literature 8. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1984. ---. Rabelais and His World.(1968) Trans. Helen Iswolsky. Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press. Helene Iswolsky. Bloomington IN: Indiana UP, 1984. Bloom, Harold. Nathaniel Hawthorne. New York: Bloom’s Literary Criticism, 2008. Dentith, Simon. Bakhtinian Thought: An Introductory Reader. London: Routledge, 1995. Hawthorne, Nathaniel. The House of the Seven Gables. New York: Pocket Books, Inc., 1950. Knowles, Ronald. Shakespeare and Carnival: After Bakhtin. London: Macmillan Press Ltd, 1998. LaCapra, Dominick. Rethinking Intellectual History: Texts, Contexts, Language. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1983. Leitch, Viencent B. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. new york: W.W. Norton & Company, 2001. Lodge, David. After Bakhtin: Essays on Fiction and Criticism. London: Routledge, 1990. Millington, Richard, H. The Cambridge Companion to Nathaniel Hawthorne. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2004. Person, S. Leland. The Cambridge Introduction to Nathaniel Hawthorne. Cambridge: www. Cambridge.org. Stallybrass, Peter. The Politics and Poetics of Transgression. New York: Cornell University Press, 1986. 18 19