Rasmussen Denmark Norway curriculum fin

advertisement

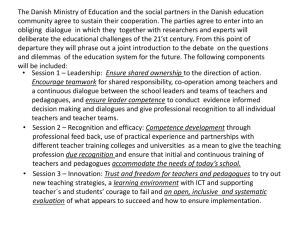

COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE DANISH AND THE NORWEGIAN CURRICULUM FOR DANISH AND NORWEGIAN LANGUAGE TEACHING PAPER PRESENTED AT NATIONAL CONFERENCE ON EDUCATIONAL SCIENCE 14-15 JANUARY 2011 HAI PHONG, VIETNAM JENS RASMUSSEN, PROFESSOR, PHD THE DANISH SCHOOL OF EDUCATION, AARHUS UNIVERSITY TUBORGVEJ 164 DK-2400 COPENHAGEN NV DENMARK JERA@DPU.DK Keywords: comparative curriculum study, Danish and Norwegian curriculum in national languages, competences, Introduction Curricula are state administrative instruments for establishing teaching practice as a part of educational policy. Their function is to express the political system’s expectations for schools and what students are to get out of school. In this way, curricula have both a social and a pedagogical-didactic function. The social function consists predominantly in making clear the expectations society has for the way schools prepare students for their future life in society, at work, and at leisure. The pedagogical-didactic function consists of making clear the expectations for teaching and learning at a particular time. In recent decades, there has been a tendency for curricula to express in ever clearer ways expectations for what students are to achieve through teaching and not what they are to be taught in, which was ordinarily the case before. At times, this displacement from content orientation to result orientation in which interest is directed toward what students get out of teaching has been designated as a paradigm shift. The expectations for what students are to get out of teaching are formulated as goals or standards. In Denmark, the development toward the target management of teaching was introduced in 2001 with so-called Clear Goals. In 2002, these guidelines were re-dubbed Common Goals and made nationally binding and expanded to include attainment goals and final goals. In 2009, these goals were revised and clarified under the title Common Goals 2009. In Norway, the development toward the target management of teaching was introduced in 1997 with Primary School Reform. However, the curriculum from 1997 was content-oriented even though clearer goal formulations were introduced. It was only with Knowledge Promotion Reform 2009 that competence goals replaced the tradition of content-oriented curricula. In this study, the Danish curriculum for Danish language instruction and the Norwegian curriculum for Norwegian language instruction will be analyzed and compared. Both curricula are introduced with the objectives for the subjects, which will not be included in this analysis, and both curricula provide attainment goals, while only the Danish curriculum provides final goals. In the Danish curriculum for Danish, there are attainment goals for grades 2, 4, 6, and 9 and final goals for grades 9 and 10. In the Norwegian curriculum for Norwegian, there are attainment goals for grades 2, 4 and 7, but no final goals. Table 1: Overview of goals Attainment goals Denmark 2 Norway 2 4 4 6 7 9 10 Final goals 9 10 The Danish curriculum Common Goals 2009 contains objectives for the subject, the subject’s attainment and final goals, a syllabus, and teaching guidelines for the subject as well as an appendix on the canon of Danish literature – a total of 71 pages (Danish Ministry of Education, (Undervisningsministeriet, 2009). The Norwegian curriculum for Norwegian contains objectives for the subject, the subject’s primary areas, provisions respecting number of hours and basic skills for the subject, and competency goals for four grades as well as provisions for assessment – a total of 16 pages (Utdanningsdirektoratet, 2010). In this comparative study, the goals and objectives of the native language curricula of the two countries will be analyzed. Goals A goal is not a clear-cut concept. A fundamental distinction can be made between content goals and performance goals. Content goals usually describe what the teacher should teach and what the students should learn. Performance goals are only directed at what learning benefits the student gets out of the teaching. Performance goals cannot be used to establish a student’s expected benefits from teaching, but they can be used to establish the skill level that students are expected to achieve at a particular point in time. Typically, a distinction is made between three forms of goals: Minimum goals, rule or normal goals, and maximum goals. (Criblez, et al., 2009; Drieshner, 2009; Ziener, 2009) - Minimum goals establish a basic level of expectation, i.e. the level that all students at a particular level must achieve. Minimum goals provide the skill level that the school must make it possible for all students to achieve. - Rule or normal goals establish the average expectation level, i.e. the skills that students as a rule achieve. Rule goals provide the average level of competence that is assumed to be realistic for a particular age group. - Maximum goals establish the highest level of expectation, i.e. the level that only the best students achieve. Maximum goals provide a theoretical highest achievable skill level. Competence goals typically concentrate on core or primary areas in individual subjects, not on the subject in its widest sense. The goals express expectations for subject or subject-overlapping skills that are of significance for later schooling and education in that they increase the possibilities for acquiring new knowledge. Thus, competence goals aim to a wide extent at developing learning-to-learn skills (Rasmussen, 2011): ’Learning-to-learn’ is the fundamental, unavoidable skill for an overall life, which must be generalized in schools in a modern, open society. (Klieme, et al., 2003, p. 66) To a broad extent, competence goals are linked with the Anglo-American concept of literacy, which is also the concept on which the PISA studies are based. This concept stands for an emphasis that basic skills must be acquired in a usable and everyday-oriented way. The German didactician Elmar Drieschner has pointed out that, to a broad extent, the Anglo-American concept of literacy is 2 compatible with the Central European concept of core competencies, since both concepts have a functional aim of understanding competencies as fundamental cultural tools. (Drieshner, 2009, p. 44) This presumption, which is the basis for the shift from content-management curricula to resultmanagement competence-oriented curricula, takes as its starting point that teaching is more effective when it is not structured from a systematic content but from the student’s process of acquisition. In other words, the focus is shifted from the content of the teaching, which becomes a means, to student learning, which becomes a goal. Areas of competence in Danish and Norwegian curricula Both the Danish and the Norwegian language curricula divide the subject into a number of core areas or, as they will be designated below, competence areas. In the Danish curriculum, the competence areas are: Spoken language, written language – reading, written language – writing, and language, literature and communication. These four areas are the same for all attainment and final goals (2, 4, 6, 9, 10). In the Norwegian curriculum, the competence areas are: Oral texts, written texts, composite texts, and language and culture. These four areas are likewise the same for the four grades (2, 4, 7, 10) for which competence goals have been set. Table 2: Competence areas with competence goals Denmark Spoken language Written language - reading Written language - writing Language, literature and communication Norway Oral texts Written texts Composite texts Language and culture At first blush, it may look as though the primary areas are the same for the two curricula and that it is merely the use of terminology that is different. However, it may quickly be seen that the Danish curriculum is oriented toward language and communication, i.e. toward something the student is to end up possessing to a greater or lesser perfection, while the Norwegian curriculum is oriented toward texts, which are rather to be understood as the content of the teaching. Performance descriptions Furthermore, each competence area is differentiated into a number of different sub-skills that are concretized by descriptions of what the students are expected to be able to do, i.e. in so-called performance descriptions. This rather high degree of complexity is illustrated in the schematic overview below. Table 3: Overview of competence areas and performance descriptions Denmark Norway Competence areas Grade Spoken language Written language reading Written language - writing Language, literature and communication Performance descriptions 2 • 4 • 6 • 9 • Competence areas 10 • Grade Oral texts Written texts Performance descriptions 2 4 7 • • • 10 • Composite texts Language and culture The concept of competency has gradually developed into a concept that summarizes what a person can or is expected to be able to do, which typically comprehends knowledge, skills, and attitudes. (Drieshner, 2009, p. 40, 45; Ziener, 2008, p. 18) Thus, a person can be designated as competent, when 3 he possesses knowledge he understands how to use and to which he can take a position. Competenceoriented curricula, therefore, must set goals that aim at providing the student with knowledge and skills as well as the capacity to reflect on his knowledge and skills. But this is not enough in itself; the student must also be capable of displaying his competencies in actions or performances. In other words, acquired competencies must be observable. This implies that the performance descriptions of curricula must be formulated in terms of what students are to achieve, i.e. be able to do (‘can do’ descriptions) as a result of the teaching. This often happens with terms such as ‘can,’ ‘master,’ ‘have at his disposal,’ ‘reflect,’ etc. Thus, performance descriptions for teaching consist of a list of competencies that students must master upon completing a grade or before leaving school. A progression will typically be built across the various grades of the overall course of study that is described in such a way that attainment goals can be seen as steps toward the final goal they are striving for. This is referred to as constructive learning or that the competencies students acquire may be considered a result of cumulative learning. Both the Danish and the Norwegian curricula have performance descriptions for individual competence areas. In the following, the performance descriptions for the competence area ’spoken language’ in the Danish curriculum and ’oral texts’ in the Norwegian curriculum, i.e. the areas marked by a bullet in table 3, will be analyzed. Analysis My analysis will focus on three aspects of the performance descriptions: 1) competence terms, i.e. whether and to what extent the goals are described so that they are observable, 2) progression and cumulativity, i.e. whether the goals are described in such a way that they relate to competencies that are described at an earlier point in the process of schooling, and 3) the type of goal, i.e. whether they express minimum requirements that all students must achieve, whether they express average requirements that middling students are expected to achieve, or whether they express maximum expectations that the best students are expected to achieve. It is immediately striking that fewer attainment goals are set for individual competence areas in the Norwegian curriculum than in the Danish. Eight goals are established for all competence areas in the Danish curriculum, while five to seven goals are set in the Norwegian curriculum. Another immediately striking observation has to do with the designations within the competence areas. The Danish curriculum mentions ’spoken language,’ which refers to a competence; while the Norwegian curriculum mentions ’oral texts,’ which refers to content. 1) Competence terms A goal that is formulated in competence or ’can-do’ terms must be able to answer the question: What do we want a student to be able to do upon completion of a grade or at the end of schooling? The student is the subject of the goal, since it is the student who is to master the competence. In this sense, goals and standards are student-oriented. However, since they are oriented toward a competence that teaching is to promote, goals are result- or process-oriented at the same time. Goals formulate what the student is to be able to do after a successful lesson or set of lessons with respect to knowledge, skills and approach, and they must be formulated so concretely that they can provide guidance for the preparation of lessons, assignments and, in principle, also for tests. Most goal formulations by far in the Danish curriculum live up to this criterion, as do all goal formulations in the Norwegian curriculum, except one. Many competence terms recur in the Danish curriculum from grade to grade and in the two final goals, while this is not the case to the same degree in the Norwegian curriculum. 4 Most of the goals by far for sub-competencies in the competence areas ’spoken language’ (DK) and ’oral texts’ (N) are formulated in such a way that it is possible to plan teaching from them and, particularly, to observe whether the individual student has achieved them. However, some goal formulations do not live up to this criterion. This has to do with goal formulations such as ’develop,’ ’understand,’ and ’master.’ For these terms, since they deal with psychological processes, it is not possible to determine whether the student has achieved the goal. To the extent it could be possible in the given case, the goals must be supplemented with signs or indicators of the student’s development, understanding or mastery. Table 4: Competence terms used Danish curriculum Attainment goals 2, 4, 6 and 9 Competence term Non-competence term Use Develop Be able to exchange Understand Present Refine Retell Tell Dramatize Give expression to Read Listen Improvise Experiment Explain Comment Interview Argue Debate Inform Express Be able to Communicate Final goals 9 and 10 Speak Use Express Read Listen Present Norwegian curriculum Attainment goals 2, 4, 7 and 10 Competence term Non-competence term Play Understand Improvise Experiment Tell Talk about Listen and give response Interact Explain Express Present Perform Listen Discuss Give Present Participate Understand and reproduce Lead and take minutes Assess Understand Master 2) Progression When standard-based curricula are introduced with attainment goals and even final goals, it is endeavoured to formulate these goals in such a way that they show a progression from grade to grade over the entire process. Ideally, the goals provide a planned sequence for when certain competencies are acquired by students. In this respect, attainment goals are directed toward cumulative learning, which implies that the content that students work with as a means to achieve these goals are constructed in such a way that it can be actualized and made actively usable in later learning processes and that acquired competencies form the prerequisite for the acquisition of other or more advanced competencies. 5 The Danish curriculum for the subject of Danish contains both attainment and final goals, which is why the attainment goals must be constructed in such a way that the intended final goals can gradually be achieved through the student’s acquisition of the competencies that the attainment goals provide. The same is not true for the Norwegian curriculum for the subject of Norwegian, since it operates solely with attainment goals and has no final goals. Here, a progression in the given case must be indicated through attainment goals without a final goal to aim for. The Danish curriculum contains a schematic overview of attainment goals and final goals from which it is easy to read how the progression from grade to grade is conceived. Nothing corresponding is found in the Norwegian curriculum. In the Danish curriculum, the competence area ’spoken language’ is divided into eight performance areas, which are the same – though with varied formulations – for all attainment goals and final goals. The competence terms are grouped into eight categories, and each category is represented at every grade. Yet, the formulations within a category may be different in that they also indicate a progression from grade to grade at the competence goal level. For example, the competence term ‘develop’ is used at grade 2 and the term ‘refine’ at grade 4, while the term ‘develop’ is used again slightly surprisingly at grades 6 and 9, even though at all grades there are allusions to the stock of concepts and vocabulary. A corresponding progression is seen in the formulations: ’Present, refer, tell, dramatise,’ Tell, explain, comment, interview, argue’, ’Argue, debate, inform’ and ‘Present and communicate.’ Table 5: Competence terms for the competence area ‘spoken language’ (DK) Competence terms 2nd grade 4th grade Use • • Develop • Refine • Present, refer, tell, dramatize • Tell, explain, comment, interview, argue • Argue, debate, inform Present and communicate Give expression to • • Express Read • • Listen • • Improvise and experiment (with body language) • Use body language (body language) • Understand • • 6th grade • • 9th grade • • • • • • • • • • • • • Every competence term or category of competence terms is described so that the competence is gradually expanded to include a broader repertoire of activities. For example, being able ’to use colloquial language’ is gradually expanded – as shown in the table below – from ’being able to listen and express oneself’ (2nd grade) to ’being able to function as moderator in a group’ (4th grade) to being able ‘to express oneself understandably and as moderator’ (6th grade) in order finally to ‘be able to lead meetings and guide discussions’ (9th grade). Only a modest difference in performance descriptions at the 4th and 6th grades can be observed. Otherwise, the individual performance area is gradually expanded in such a way that more is added to competencies already acquired. Table 6: Performance descriptions for pt. 1 in the competence area ’spoken language’ (DK) 2nd grade In conversation and work, being able to shift between listening and expressing 4th grade In conversation, collaboration, and discussion, acting as moderator in a group 6th grade Understandably and clearly in conversation, collaboration, and discussion, functioning as moderator 9th grade Leading meetings and guiding discussions 6 The final goals toward which the attainment goals in the Danish curriculum are aiming for the students to achieve are formulated in more general performance statements than in the attainment goals: ’’to speak understandably, clearly and in a varied form appropriate to the situation’ (9th) and ‘to express one’s own opinions in discussions and to assess what is sound argumentation’ (10th). The Danish curriculum aims at a progression from grade to grade – however, not always with clearly new or intensified performance descriptions and performance expectations. In principle, there is an endeavour, but not always in reality, to make the acquired competencies a prerequisite for the acquisition of more advanced competencies in a cumulative learning process. The goals in the Norwegian curriculum are not gathered around the same competence terms from grade to grade in the same way as the Danish. Goals are provided for some competencies at many grades, but no competencies are provided goals at every grade. At individual grades, the same competence is stated several times with a different performance description. Table 7: Competence terms for the competence area ’oral texts’ (N) Competence terms 2nd grade Play, improvise and experiment • Express • Tell • Talk about •• Listen and give response • Interact Explain Express Present Perform Listen Discuss Give Present Participate Understand and reproduce Lead and take minutes Assess 4th grade 7th grade 10th grade • • • • • • • • • •• • • • • • • • • Since the competence terms for individual goals are different from grade to grade, the performance descriptions will be as well. Thus, it is difficult to see a clear progression in the Norwegian curriculum. An example that emphasizes this especially clearly has to do with the performance description respecting the Scandinavian languages Danish, Norwegian and Swedish. In the Danish curriculum, there are competence goals for Norwegian and Swedish at all grades, while in the Norwegian curriculum there are only competence goals for Danish and Swedish at the 10th grade. Thus, the Norwegian curriculum must be said to provide guidance in only a minor (modest) way for cumulative learning processes. 3) Goal type The Danish and the Norwegian curricula operate only with rule or normal goals for, respectively, Danish and Norwegian. This means that both curricula only state a middle or average requirement level for the desired competencies. Rule goals are ordinarily defined empirically, i.e. from practitioners’ experiences and evaluations. 7 Rule goals will typically direct the teacher’s attention toward the middle group of students, since these goals are formulated from a tacit assumption that students’ competencies are normally allocated differently, albeit so that a majority of students will achieve these goals. By orienting themselves toward an average level, rule goals reflect a widespread ‘normal allocation’ mindset that finds it ’natural’ for student performance to be allocated in accordance with a normal distribution curve with a greater or lesser number on each side of a fictive average. In other words, rule goals strengthen the focus on the middle group that strikes the teacher as natural. In this way, both weak and strong students fall outside the teacher’s field of vision, so to speak. Thus, in principle, rule goals help strengthen the tendency to orient teaching toward the average student, as the first professor in pedagogy Ernst Christian Trapp pointed out in Versuch einer Pädagogik from 1780. Here, he writes that teachers typically relate to the heterogeneity of school classes by orienting and calibrating the teaching in accordance with an imaginary average or in accordance with average students, which he designates as ’Mittelköpfe.’ (Trapp, 1977 (1780)) There is much to indicate that this is still the case in the comprehensive schools of the day, which can be read from the fact that the middle group of students in both Denmark and Norway achieve quite acceptable results in school, while this is not the case, cf. the PISA studies, for weak and strong students. (OECD, 2007) A number of European countries, including Denmark and Norway, have decided to introduce rule goals. Maximum goals are often rejected, because they imply that rule goals and minimum goals would be formulated negatively as a deviation from an ideal. The choice of rule goals implies with great probability that the problem of the comprehensive school – namely, that both weak and strong students attain poorer results from their schooling – is reinforced. Instead of choosing one standard type, the possibility exists for choosing minimum goals and rule goals or maybe all three goal types and letting them complement each other. Minimum goals are characterized by putting a focus on weak students. Many students even at the beginning of a grade have already met the minimum goal – often, even without the school’s efforts. Many students will follow at different tempos, while some individuals will not achieve the goal within the established time period. It is this latter group of students around which attention may gather, since they must be offered special help to achieve the goals that everyone is to achieve. Maximum standards are specific goals for what the best students are expected to achieve. Often, the number of students who are expected to achieve these goals as a percentage is stated. By their nature, maximum standards direct the teacher’s attention toward strong students. 8 By using several goal types and by letting them complement each other, the teacher’s opportunities for being attentive to weak students, strong students, and the large middle group of students, in which none of these groups need to be the same in all subjects and at all times, are increased. Conclusion The Danish and the Norwegian curriculum in Danish and Norwegian language show a number of equal signs. Both countries have introduced goal based curricula. The goals are arranged around few main areas of the subject, not around the subject in its full extent. To each of the competence areas a number of competence goals are stated along with performance descriptions. The goals are intentionally formulated so that they show progression from grade to grade, and attainment goals are stated for selected grades, but only the Danish curriculum has final goals. The two curricula also show a number of differences. In the Danish curriculum the competence areas are oriented toward language and communication, i.e. toward something the student is to end up possessing, while competence areas in the Norwegian curriculum are oriented toward texts, i.e. toward content of the teaching. Each curriculum aims at progression from grade to grade. In the Danish curriculum the competence goals are formulated so that the competence is gradually expanded over the course of school years. In the Norwegian curriculum mostly new competence goals are stated for every grade, which means that it is difficult to see a clear progression over the course of school years. Both the Danish and the Norwegian curriculum for Danish and Norwegian language aims at being goal oriented competence based curricula but it seems like the Norwegian curriculum does not release its hold on content oriented curriculum thinking. Bibliography Criblez, L., Oelkers, J., Reusser, K., Berner, E., Halbheer, U., & Huber, C. (2009). Bildungsstandards. Seelze-Velber: Klatt-Kalmeyer. Drieshner, E. (2009). Bildungsstandards praktisch. Perspektiven kompetenzorientierten Lehrens und Lernens. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften. Klieme, E., Avenarius, H., Blum, W., Döbrich, P., Gruber, H., Prenzel, M., et al. (2003). Zur Entwicklung nationaler Bildungsstandards - Expertise Available from http://www.bmbf.de/pub/zur_entwicklung_nationaler_bildungsstandards.pdf OECD (2007). PISA 2006. Paris: OECD. Rasmussen, J. (2011). Moderne pædagogik - refleksionsteori mellem praksis og forskning. In H. J. Kristensen & P. F. Laursen (Eds.), Gyldendals pædagogikhåndbog. København: Gyldendal. Trapp, E. C. (1977 (1780)). Versuch einer Pädagogik. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh. Undervisningsministeriet (2009). Fælles Mål 2009 Dansk. Retrieved from http://www.uvm.dk/~/media/Publikationer/2009/Folke/Faelles%20Maal/Filer/Faghaefter/090 707_dansk_24.ashx Utdanningsdirektoratet (2010). Norwegian Subject Curriculum. Retrieved from http://www.udir.no/Artikler/_Lareplaner/_english/Common-core-subjects-in-primary-andsecondary-education/ Ziener, G. (2008). Bildungsstandards in der Praxis (2 ed.). Seelze-Velber: Klett, Kallmeyer. Ziener, G. (2009). Bildungsstandards in der Praxis: Kompetenzorientiert unterrichten. Seelze-Velber: Klett, Kallmeyer. 9