Coral Reefs Face Extinction

advertisement

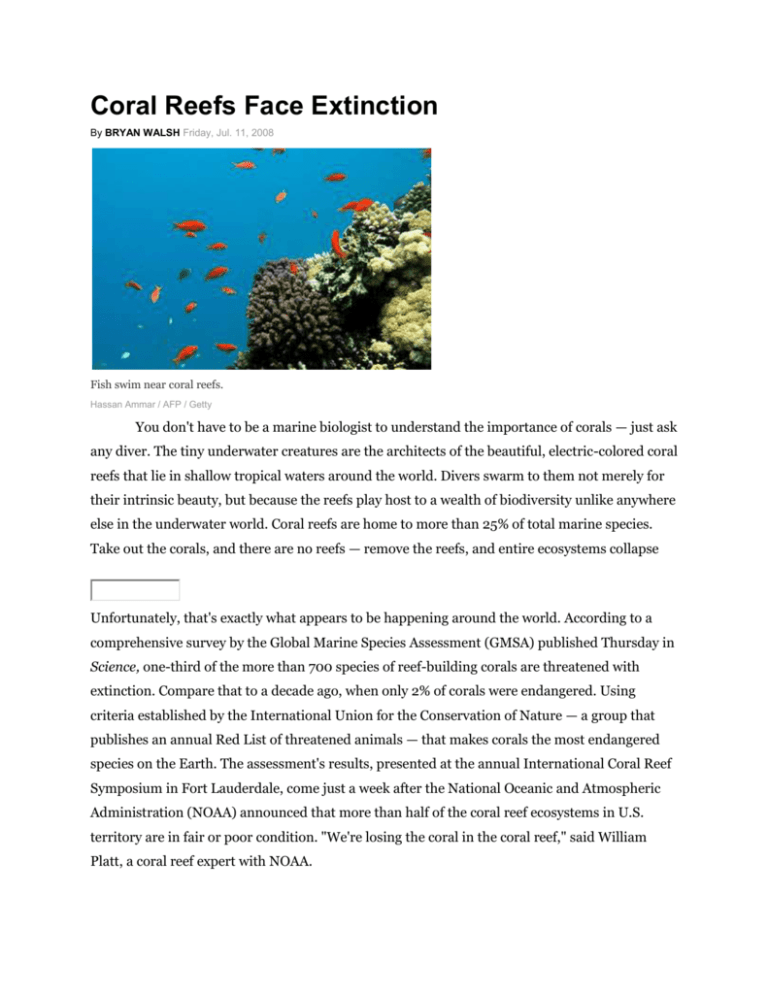

Coral Reefs Face Extinction By BRYAN WALSH Friday, Jul. 11, 2008 Fish swim near coral reefs. Hassan Ammar / AFP / Getty You don't have to be a marine biologist to understand the importance of corals — just ask any diver. The tiny underwater creatures are the architects of the beautiful, electric-colored coral reefs that lie in shallow tropical waters around the world. Divers swarm to them not merely for their intrinsic beauty, but because the reefs play host to a wealth of biodiversity unlike anywhere else in the underwater world. Coral reefs are home to more than 25% of total marine species. Take out the corals, and there are no reefs — remove the reefs, and entire ecosystems collapse Unfortunately, that's exactly what appears to be happening around the world. According to a comprehensive survey by the Global Marine Species Assessment (GMSA) published Thursday in Science, one-third of the more than 700 species of reef-building corals are threatened with extinction. Compare that to a decade ago, when only 2% of corals were endangered. Using criteria established by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature — a group that publishes an annual Red List of threatened animals — that makes corals the most endangered species on the Earth. The assessment's results, presented at the annual International Coral Reef Symposium in Fort Lauderdale, come just a week after the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) announced that more than half of the coral reef ecosystems in U.S. territory are in fair or poor condition. "We're losing the coral in the coral reef," said William Platt, a coral reef expert with NOAA. The causes of the coral's demise are manifold, but they all come back to one culprit: us. Overfishing — especially the kind that uses dynamite or poison to kill whole schools of fish — destroys the coral directly, while polluted runoff from agriculture simply chokes them. Development in booming coastal economies from the Caribbean to Southeast Asia further threaten the delicate reefs. Tourism — in the form of diving and snorkeling — can also cause damage. As with so many other endangered species around the world, there doesn't seem to be enough space for healthy coral reefs and unchecked human development. "It's just a litany of bad actions," says Brian Huse, the executive director of the Coral Reef Alliance. "Over the past 35 to 50 years, we've lost 25% of our reefs worldwide. Put it altogether, and you can see why." Disease plays a role as well, with whole coral colonies wiped out by sudden sickness. That rise in illness may be linked to warmer sea temperatures, which is caused by climate change. And it's global warming that poses the most serious threat to the survival of coral. Corals have a symbiotic relationship with a kind of algae that provide nutrients and energy through photosynthesis — not to mention the vivid colors we associate with coral reefs. When corals are stressed by rising temperatures, the algae are expelled by the coral, turning the reefs bone white. That's a "bleaching event," and bleached coral are left weakened and defenseless against disease. Increased carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere also lead to more acidic seas, which impairs the ability of corals to form their skeletal reefs. (In acidic water, the reefs simply dissolve.) "Corals appear to be particularly sensitive to the buildup of CO2," says Kent Carpenter, the lead author of the Science study and the director of GMSA. "The corals will be the canary in the coal mine in terms of the effect climate change will have on our oceans." In one way, protecting the coral is not that different from protecting any endangered species. First, we need to cut back on activities that ruin their habitat, the shallow waters close to our coast. Agricultural runoff — already responsible for the oceanic "dead zones" seen in the Gulf of Mexico and other heavily built up coasts — has to be curtailed, as does the senselessly destructive fishing practices that have us tossing dynamite or poison into the waters. One of the best strategies is to expand the range of territory protected by marine reserves — national parks of the deep. And here the Bush Administration — usually anything but environmental — deserves real credit. With a stroke of a pen in 2006, President George W. Bush created the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument, a 140,000 sq. mi. protected area northwest of Hawaii. Larger than every other national park in the U.S. combined, the monument protects 10% of the shallow coral reef habitat in U.S. territory. These kind of reserves need to be expanded, to limit the influence of human activity on delicate corals. But we could make the entire ocean into a marine park and still lose the coral, if we can't stop climate change. As temperatures rise in the ocean, bleaching events will become more and more common. According to a study published in Science late last year, if CO2 levels continue rising unabated, by 2100 coral could be utterly extinct. "If we can't contain the CO2 problem and enact strong coral reef conservation measures, we will lose them," says Carpenter. The depressing fate of the coral could be a reminder that climate change has the power to undo all the work of wildlife conservation over the past century — if we let it. http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1821971,00.html (TECHNOLOGY IN ARTICLE BELOW WITH HELPFUL INFORMATION) Trying to Save the Coral Reefs By KRISTA MAHR Friday, Aug. 17, 2007 A school of fish pass over a coral reef at Hanauma Bay, Hawaii. Donald Miralle / Getty Near the close of the 1960s, a squadron of young scuba divers headed out into the warm waters of the South Pacific, tanks of air strapped to their backs and syringes at the ready. Their mission, one lethal injection at a time, was to put a stop to an outbreak of crown-of-thorns starfish, a voracious predator of fragile tropical coral reefs. Those early efforts — along with a big printing of "Save the Barrier Reef" bumper stickers — helped establish what has since been considered one of the world's best-protected coral reefs. Bottom of Form More than 30 years later, some of those dive bums have grown up to become full-fledged coral ecologists, and what they are seeing today is probably making them long for the halcyon days of the '60s. Rising ocean temperatures, compounded by other man-made factors, like pollution and overfishing, have been catastrophic for the earth's coral. "I grew up diving and snorkeling all over the world," says Gregor Hodgson, executive director of the coral monitoring organization Reef Check Foundation. "Those reefs are all gone." On August 7, researchers at the University of North Carolina released the world's first comprehensive study on coral in the Indo-Pacific region, which stretches from Japan to Australia and east to Hawaii, and is home to 75% of the world's coral reefs. The outlook is grim. Between 1968 and 2003, more than 600 sq. mi. of reef disappeared in the region — that's 1% a year, twice the pace of rainforest decline — and the losses are hitting well-protected areas like the Great Barrier Reef just as hard as the stressed, overfished reefs that surround crowded countries like the Philippines. "People thought the Pacific was in much better shape," says John Bruno, lead author of the study, which was published online by the Public Library of Science. Scientists assumed that far-flung reefs in the vast waters of the Pacific would be safely isolated from negative human impact. They were wrong. "There is no such thing as an isolated reef from the perspective of climate change," says Bruno. The UNC report coincides with separate accounts of another widespread scourge: in July, coral reefs in the South China Sea and around the Florida Keys and Caribbean started to bleach — a result of warming waters. Healthy reefs live symbiotically with algae, which takes shelter inside the coral and, in return, passes nutrients to its host. When waters reach an uncomfortably high temperature, coral gets stressed and kicks the algae out, which turns the coral white and essentially starves it to death. Local reef watchers have contacted the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) from the northern Philippines to southern Japan, some warning that their coral is bleaching nearly as much as it did in 1998, when El Ni�o–heated waters killed 15% of the world's reefs. Like the busily receding glaciers in the Arctic, coral reefs are a canary in the global warming coal mine. "They are a sensitive species that are affected first," says C. Mark Eakin, coordinator of NOAA's Coral Reef Watch program, which warns scientists when their part of the world is at risk for bleaching. And though climate change awareness is up, and embattled reefs do get moments of compassion, the public has a short attention span when it comes to ecosystems it can't see. So do policy makers. Bruno says more coral data is being gathered today by non-governmental organizations than universities or government programs, particularly in developing nations where the focus is more on building hospitals and roads than on marine science. But even in the U.S., NOAA's satellite data program, alert system and monitoring are second to the larger network of local groups and governments keeping watch over the U.S. reefs. "Nobody wants to pay for monitoring because it's boring," says Hodgson. That's why he founded Reef Check. Realizing that one man's chore might be another's hobby, Hodgson decided to fill the information gap by enlisting people who were naturally interested: divers. In 1997 he created a global network of volunteer snorkelers and divers, specially trained by scientists to monitor reefs using a standardized checklist. Over the last 10 years, Reef Check's volunteers have amassed a bounty of data on the world's coral. "In the beginning, people were looking down on us, saying 'Oh, you guys are just volunteers,'" Hodgson recalls. Now, Reef Check has become one of the primary sources of scientific information about coral health. Why the need to monitor coral so closely? Coral reefs constitute a complex and vast global ecosystem, home to millions of species of plants and fish that people depend on for food and tourist revenue; in some areas, healthy reefs help protect the shore from potentially destructive waves. But arguments about the preservation of biodiversity make eyes glaze over, so Hodgson, who's trying to get coral on the World Conservation Union's red and endangered species lists, likes to point out that several anticancer drugs are derived from reef species. "Maybe one day a coral will save your life," Hodgson tells skeptics. "That gets to people." Perhaps the single best advocate for the preservation of coral reefs is the reefs themselves. In many parts of the world, conservationists are letting the natural beauty and allure of the reefs — which generate about $1.6 billion annually in tourist dollars — do the talking for them. In one area of the Philippines, for instance, local leaders asked fishermen who had been making a living by blast-fishing, which destroys reefs, to trade in their trawlers for dive boats. They did, the fish came back to the reefs, the local economy flourished and everybody — tourists, residents, and coral ecologists alike — was happy. In cases like these, one hand washes the other, says NOAA's Eakin. "If healthy coral reefs are your bread and butter, you're going to make sure they're in good shape." It remains to be seen whether local solutions, like ecotourism or the establishment of marine parks, will create lasting changes. No one knows when the warm waters causing the current bleaching epidemic will recede, and once coral starts dying in warm currents, there isn't a lot that scientists can do but sit back and watch. Some reefs may recover, but others won't, and researchers are still trying to figure out why. "I don't think there's any way you can manage for a global effect locally," says Bruno, the author of the UNC report. He thinks the root cause of disappearing coral is, in the end, climate change, which can be addressed only by a worldwide effort to cap fossil-fuel use and pass stringent climate change legislation. "If we only manage locally, [we] will be totally overwhelmed over the next century." http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1653804,00.html?iid=sphere-inline-sidebar