NPO vs. CL, CHO

advertisement

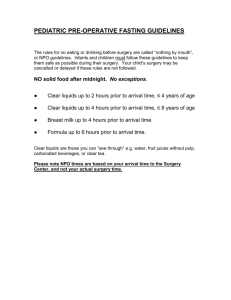

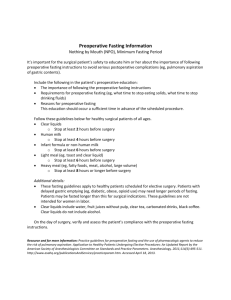

Running Head: NPO AFTER MIDNIGHT VS. NPO AND CLEAR LIQUIDS/CHO PICO Paper Charles J. Adler NURS 612: PICO Paper Prof. Pam Kallmerten RN, MSN, CNL University of New Hampshire March 27th, 2015 1 Running Head: NPO AFTER MIDNIGHT VS. NPO AND CLEAR LIQUIDS/CHO 2 Abstract A traditional preoperative instruction given to patients is to remain NPO after midnight. The rationale behind this is to prevent gastric aspiration and potential fatality in the OR. Though this is a severe concern, the incidence of this event is quite rare. This recommended instruction has been preserved by tradition and ritual as opposed to evidence. With support from up to date reviews and clinical trials, a more “flexible” NPO alternative diet has been introduced in attempt to address symptoms that clients have reported in the preoperative and postoperative periods. The goal is to understand the difference between prolonged fasting and the intake of clear liquids with carbohydrates before surgery. To determine the effectiveness of these interventions in reducing incidence of aspiration and accompanying complications, evidence will be gathered, synthesized, and appraised under the criteria of maintaining patient safety and striving for optimal wellness in clients electing surgery. Keywords: NPO after midnight, Clear Liquids/CHO, Gastric aspiration, Post Op Running Head: NPO AFTER MIDNIGHT VS. NPO AND CLEAR LIQUIDS/CHO 3 In adult preoperative patients scheduled for surgery in the OR, what are the effects of a “strict” NPO diet after midnight to reduce incidence of intraoperative aspiration and other pre and postoperative complications, compared to a “flexible” NPO diet consisting of clear liquids and intake of carbohydrate rich solutions? Title PICO Population Intervention Compared to… Outcome Preoperative adult patients scheduled for next day surgery “Strict” NPO after midnight before surgery “Flexible” NPO with clear liquids and CHO before next day surgery Reduced incidence of intraoperative aspiration, pre and postoperative complications Background & Rationale Patients who are scheduled for surgery will often be instructed to withhold the intake of food or liquids the night before their elective procedure. Traditionally, surgeons will recommend this instruction to begin after midnight the night before the surgery. This order is often seen in expression as “NPO”, “Nothing by mouth”, or “nil per os”. Conventionally, this order was given to patients to reduce the risk and incidence of gastric aspiration under the induction of anesthesia. Mendelson’s syndrome, or aspiration pneumonitis, is an anesthesia related complication that is a rare event in today’s hospitals (Webster & Osborne, 2014). Though its incidence is uncommon, the regurgitation of stomach contents into the lung can be a fatal consequence. Mechanically, the swallowing mechanisms including pharyngeal and laryngeal nerve reflexes are temporarily seized due to anesthetic induction (Oshodi, 2004). While the patient is in a state of stupor, all voluntary and involuntary swallowing capabilities are halted, placing the patient at a high risk for gastric regurgitation and aspiration if stomach contents are present. Theoretically speaking, this is why the order to maintain NPO after midnight is so important because it is believed that the Running Head: NPO AFTER MIDNIGHT VS. NPO AND CLEAR LIQUIDS/CHO 4 optimal approach to reducing aspiration risk is ensuring an empty stomach on the day of surgery (Crenshaw, 2011). To ensure maximum safety regarding the fatal risk of intraoperative aspiration, NPO guidelines after midnight have been conservatively enforced. With such strict and prolonged fasting times for patients, it is evident that many clients experience great discomfort with this request, reporting symptoms such as hunger, dizziness, headaches, and irritability before surgery (Reimer-Kent, 2010). In addition to subjective patient reports, excessive fasting can also extend patient stay in the hospital and delay post-operative recovery (Romit & Mortel, 2011). Contrary to the standard preoperative order of NPO after midnight, the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) established guidelines in 1999 that favor more flexible fasting options before surgery. These options include the intake of clear liquids up to two hours before surgery and the intake of a carbohydrate rich solution both to promote gastric emptying, assist in postoperative recovery, and overall reduce the incidence of gastric aspiration (Apfelbaum, 2011). Operative interventions such as differing preanesthesia fasting instructions are important to implement with support from evidence and clinical significance. Evidenced based practice is the backbone of most nursing interventions that are instilled in the clinical setting. A paradigm such as this exemplifies the importance of patient safety and achieving optimal client outcomes based on empirical data and literature reviews. It is here that differing preoperative fasting interventions will be compared and assessed using evidence, clinically significant appraisals, and client trials to conclude the most appropriate fasting intervention that will ensure intraoperative safety, optimal wellness, and quickened post-operative recovery in patients electing surgery. Search Methods Running Head: NPO AFTER MIDNIGHT VS. NPO AND CLEAR LIQUIDS/CHO 5 To retrieve information regarding preoperative fasting and diet alternatives, the primary database used was the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). The following are key words that were inputted into CINAHL database: “NPO”, “surgery”, “NPO after midnight”, “preoperative fasting”, and “Mendelson’s syndrome”. In combination, these terms yielded over 50 results, including analyses, reviews, and academic journals. To narrow this list, limit conditions were placed on the search, only allowing for full text reviews, imbedded references, publication 2000 to 2015, and English language. The new search with limits yielded roughly 20 results that were relevant and applicable to the nursing interventions. When gathering citations, it is important to collect only those that adhere to inclusion criteria that is established by the searcher. For this compilation, citations were gathered only if they acknowledged the legitimacies of ASA preoperative fasting guidelines, which included fasting for 2 hours after ingesting clear liquids, 4 hours after breastmilk, 6 hours for infant formula, nonhuman milk, and or a light meal, and 8 hours for a “dense” meal containing fried or fatty foods (Apfelbaum, 2011). In addition to fasting criteria, the citations used must also have strictly featured adults in its trials electing surgery as opposed to an emergent procedure. The trials searched must also have contained data regarding the evaluation and comparison of preoperative fasting alternatives, such as clear liquids and carbohydrate solutions, which would promote client safety and compliance. Furthermore, only evidence based reviews and clinically significant appraisals were accepted regarding the incidence of intraoperative gastric aspiration and potential postoperative complications. (Exclusion criteria included studies involving pediatric surgeries, emergent procedures, unsourced appraisals, and unreferenced reviews.) Search engines such as Google Scholar and “UpToDate” were utilized to assist in a pathophysiological understanding of gastric aspiration and recognizing NPO guidelines. Running Head: NPO AFTER MIDNIGHT VS. NPO AND CLEAR LIQUIDS/CHO 6 Between search engines and databases, the estimated number of included citations range from 12-15. Few citations highlighted clinically controlled trials, while others presented evidence to promote the elimination of NPO after midnight. With each satisfying the inclusion criteria, citations were analyzed and appraised in relevance to the posed PICO question of determining the most appropriate nursing intervention to achieve the stated desired outcome. Critical Appraisal of Evidence The first citation to be appraised originates from Spain’s Hospital Nutrition Magazine, presented as a scientific journal of health science. The research journal was accessible in English, meeting the necessary inclusion criteria. As reflected in the subtitle, this “double-blind, controlled, and randomized clinical trial” targets preoperative fasting to include the ingestion of a carbohydrate rich solution with glutamine components up to 2 hours before anesthetic induction of elective laparoscopic cholecystectomies (Borges Dock-Nascimento et al., 2011). To determine the safety of this “abbreviated” fasting ritual, a nasogastric tube is inserted to measure the residual gastric volume (RGV) of stomach contents after being anesthetized. RGV is ultimately determined by the predicted evacuation of the stomach and the emptying rates in which fluids are guided to the small intestine via peristalsis (Crowley, 2014). 56 women participated in randomized control trials. Women were randomly assigned to either adhere to a traditional fasting of 8 hours before surgery (n=12), drink a placebo of water the evening before and 2 hours prior to surgery (n=12), drink a carbohydrate solution (n=12), or drink a glutamine mixture (n=14) both following the same fluid guidelines as the placebo. After a few surgery cancellations and participant refusals, 50 women completed the trial. Results suggest that no participants had suffered from intraoperative gastric regurgitation or significant postoperative complications. With the determined RGV in the varying fasting alternatives, it was found that Running Head: NPO AFTER MIDNIGHT VS. NPO AND CLEAR LIQUIDS/CHO 7 each intervention produced a similar volume of gastric contents with a median range between 080mL of fluid. No one intervention consistently produced a RGV of 0mL, nor did an intervention consistently exceed 80mL. It is concluded that the ingestion of clear liquids, carbohydrate solutions, and glutamine mixtures (when concentrated and measured according to this trial) 2 hours before surgery will not increase RGV, nor will it rise the incidence of gastric aspiration when under anesthesia, deeming it a safe practice. Strengths of this trial include its physiological focus on gastric emptying and its direct relationship with RGV. It also emphasizes the importance of varying evacuation rates based on fluid consistency. In the discussion analysis section of the article text, it announces the potential benefits of ingesting a carbohydrate/glutamine solution in regards to postoperative recovery and complications. Though it is solid in its experimental trials, the study is restricted in its surgical criteria, meaning it lacks experimentation in more diverse surgeries beyond gall bladder removal. Additionally, this clinical trial only targets women undergoing this surgery. This gender bias is considered a weakness in its product, excluding the male population with potentially differing RGV and incidence of complication. The weaknesses of the trial may or may not have been responsible for such uniform results among trial groups. Statistically, a 5% significance level was accepted with a corresponding p value of 0.29, proving results to be statistically insignificant, allowing for a retained null hypothesis (all interventions are equal in outcome or difference happened by chance). A second citation found addresses preoperative fasting and carbohydrate loading before surgery. As acknowledged in the article’s title, the evidence which has been gathered for decades regarding preoperative fasting has yet to be implemented in today’s practice. It is understood that a prolonged fasting time for a pre-surgical patient could consequent a variety of Running Head: NPO AFTER MIDNIGHT VS. NPO AND CLEAR LIQUIDS/CHO 8 discomforts including hunger, thirst, dizziness, drowsiness, and anxiety (Crenshaw, 2011). These symptoms would manifest before surgery, only exacerbating the patient’s own anxieties regarding the procedure. To measure these somatic reports and the incidence of other complications such as insulin resistance, dehydration, muscle wasting, hyperglycemia, and impaired immune function, a qualitative study was performed in Sweden, targeting patients scheduled for abdominal surgery. A double blind, randomized control trial incorporated 252 Swedish adult patients, each assigned to either a traditional 8 hour fast, a placebo group to ingest water, or a group told to ingest a carbohydrate rich clear beverage the night and 2 hours before surgery. After about an hour into anesthesia, stomach contents were aspirated and analyzed. No significant difference in RGV was found between participants and their corresponding preoperative diet. Results show that clients who ingested the carbohydrate rich solution reported significantly less symptomatic distress before induction. Those participants in the placebo and NPO after midnight groups reported higher incidences of thirst, hunger, and anxiety before going under anesthesia. According to Borges Dock-Nascimento et al. (2011), a carbohydrate rich beverage in the preoperative period may also decrease the body’s catabolic stress response to surgery, promoting a speedy recovery in the postoperative setting. This trial is strong by targeting preoperative symptoms and postoperative recovery after the intake of a preoperative diet. It is important to address discomforts going into surgery for they could ultimately affect the patient’s recovery. The research, however, failed to provide details in the methods in which qualitative data was recorded and whether surveys were conducted to ask clients to describe their anxiety, etc. Evidence Synthesis Running Head: NPO AFTER MIDNIGHT VS. NPO AND CLEAR LIQUIDS/CHO 9 Each appraised citation offered valuable insight regarding preoperative fasting rituals and their repercussive effects on the body. After weighing the evidence and analyzing clinical significance, it can be confidently concluded that preoperative dieting should include a clear liquid carbohydrate solution two hours before the scheduled procedure as opposed to remaining NPO after midnight. Prolonged fasting is a detriment to the patient’s preoperative period, causing increased anxiety and agitation that is essentially caused by a lack of oral intake. With such strict NPO guidelines based on the traditional 8 hour fast, it is likely for patients to become noncompliant with the order, creating a very serious safety risk that surgeons must be aware of (Kramer, 2000). In addition to preventing optimal wellness, breaking strict NPO instruction can also delay a patient’s surgery, potentially causing added harm to the patient if not operated on when originally scheduled. In the intraoperative period, it is of vital importance that the client’s stomach is nearly empty of all contents in order to prevent Mendelson’s syndrome associated with anesthesia. Based on the research provided, it is concluded that gastric aspiration has an extremely low incidence in today’s operating rooms. Specifically, 1 out of every 2,000-3,000 operations result in some degree of gastric regurgitation (Brown & Heuberger, 2014). Though rare, gastric aspiration is a fatal complication that is believed to be related to RGV. Additionally, research shows that NPO after midnight and clear liquids 2 hours before result in very similar residual gastric volumes, suggesting that one preoperative diet method is just as effective as the other in relation to intraoperative incidence of aspiration. In the post anesthesia period, the body begins to adjust back to its normal functioning which includes regaining the ability to swallow, consciously breathe, etc. Research has shown that the intake of clear liquids and carbohydrates 2 hours before surgery can improve the body’s Running Head: NPO AFTER MIDNIGHT VS. NPO AND CLEAR LIQUIDS/CHO 10 stress response by decreasing insulin resistance. Clear liquids also produce an anabolic state of metabolism which will help “rebuild” and energize the body after surgery by using up the CHO reserves ingested during preop (Brown & Heuberger, 2014). Understandably so, patients are more likely to have a shorter hospital stay as their postoperative recovery advances (Crenshaw, 2011). In conclusion, it is suggested to adhere to a preoperative diet of a carbohydrate/clear liquid solution 2 hours before surgery in order to promote optimal healing and allow for an efficient and productive postoperative recovery. In adult preoperative patients scheduled for surgery in the OR, what are the effects of a “strict” NPO diet after midnight to reduce incidence of intraoperative aspiration and other pre and postoperative complications, compared to a “flexible” NPO diet consisting of clear liquids and intake of carbohydrate rich solutions (CHO)? In relevance, all evidence and reviews have been appraised in regards to the question… The presented evidence has addressed the effects of a “strict” NPO diet in all three realms of surgery: preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative. In synthesis, the data was compared to a “flexible” NPO diet consisting of clear liquids and carbohydrate solutions. In regards to intraoperative aspiration, the overall incidence is rare so it is concluded that either diet is favorable in that respect. In the preoperative stage, clear liquids and CHO is the recommended diet, for this intervention is likely to reduce symptoms such as anxiety, agitation, hunger, and thirst before induction. Prolonged fasting with NPO after midnight can also cause unnecessary complications such as hypovolemia and confusion (Oshodi, 2004). Finally, in the postoperative period, clear liquids with CHO promote healing and quickened recovery. Clinical & Research Recommendations Running Head: NPO AFTER MIDNIGHT VS. NPO AND CLEAR LIQUIDS/CHO 11 The evidence suggesting that clear liquids and carbohydrates 2 hours before surgery is safe and a more comfortable preoperative diet is overwhelmingly supported by articles, clinical trials, and blind studies. It is my clinical recommendation that this research is distributed to all surgeons, OR nurses, CRNA’s, anesthesiologists, etc. In doing so, it is my hope that healthcare professionals will guide their practice through streamlined and up to date nursing evidence. It is evidence based practice that governs nursing interventions as the most important outcome remains to be patient safety. Educational seminars are also important in the clinical setting for it would provide valuable knowledge about preoperative teaching and potentially change the way in which patients are instructed to prepare for surgery. Additional research is necessary to solidify this intervention and begin to implement it into clinical practice. For example, research regarding emergent procedures are important to assess because the patient obviously does not have the time to adhere to an NPO restriction of any kind. Could this alter the incidence of gastric aspiration? Additionally, it would be helpful to understand a patient’s comorbidities and how they may affect the risk of complications in any of the three stages of surgery. In the evidence provided, the included surgeries were only abdominal. It would be wise to trial other types of surgeries, such as bariatric or pediatric, in regards to incidence of aspiration. Finally, I believe that studies must be conducted containing larger populations. With an increase in participants, it is more likely to produce evidence that is statistically significant, meaning the difference in outcomes did not occur by chance. It is my hope that with increased populations in trials and further evidence validity, operating rooms around the country will begin to fade out NPO after midnight instructions and elevate orders to include the intake of clear liquids and carbohydrate solutions 2 hours before surgery. Running Head: NPO AFTER MIDNIGHT VS. NPO AND CLEAR LIQUIDS/CHO 12 References Allison, J., & George, M. (2014). Using Preoperative Assessment and Patient Instruction to Improve Patient Safety. AORN Journal, 99(3), 364-375. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2013.10.021 Apfelbaum, T. (2011.). Practice Guidelines For Preoperative Fasting And The Use Of Pharmacologic Agents To Reduce The Risk Of Pulmonary Aspiration: Application To Healthy Patients Undergoing Elective Procedures. Anesthesiology, 495-51 Borges Dock-Nascimento, D., Aguilar-Nascimento, J., Caporossi, C., Sepulveda Magalhaes Faria, M., Bragagnolo, R., Caporossi, F., & Linetzky Waitzberg, D. (2011). Safety of oral glutamine in the abbreviation of preoperative fasting: a double-blind, controlled, randomized clinical trial. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 26(1), 86-90. doi:S021216112011000100009 Brown, L., & Heuberger, R. (2014). Nothing by Mouth at Midnight. Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates, 37(1). Retrieved from http://www.nursingcenter.com/lnc/pdfjournal?AID=1690312&an=00001610-20140100000002&Journal_ID=&Issue_ID Crenshaw, J. T. (2011). Preoperative Fasting: Will the Evidence Ever Be Put into Practice?. American Journal Of Nursing, 111(10), 38-45.12&an=00001610-20140100000002&Journal_ID=&Issue_ID Engelhardt, T., & Webster, N. (2000). Pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents in anaesthesia. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 453-460. Kramer, F. (2000). Patient perceptions of the importance of maintaining preoperative NPO status. AANA Journal, 68(4), 321-328. Marsh, M. L., Webster, J., & Osborne, S. R. (2014). NPO practices and preoperative oral carbohydrate intake... “Does preoperative oral carbohydrate reduce hospital stay? A randomized trial” by Webster et al (February 2014, Vol 99, No 2). AORN Journal, 99(6), 672-673. doi:10.1016/j.aorn.2014.03.006 Oshodi, T. (2004). Clinical skills: an evidence-based approach to preoperative fasting. British Journal Of Nursing, 13(16), 958-962. Reimer-Kent, J. (2010). Did you know? ...NPO after midnight is not best practice. Canadian Journal Of Cardiovascular Nursing, 20(1), 22. Romit, J. A., & van de Mortel, T. (2011). Ritualistic preoperative fasting: is it still occurring and Running Head: NPO AFTER MIDNIGHT VS. NPO AND CLEAR LIQUIDS/CHO what can we do about it?. ACORN: The Journal Of Perioperative Nursing In Australia, 24(1), 14. 13