Graduates and SMEs - Stephen McNair`s Website

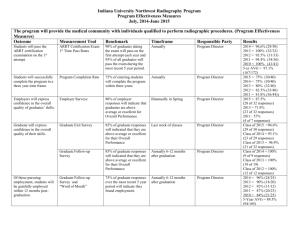

advertisement