Gender Identity Issues and Bioethics

advertisement

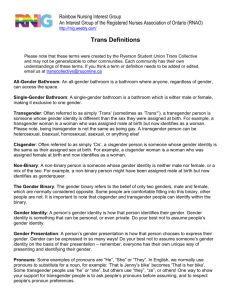

Legal-Institutional Sex vs. Gender Identity: Cisnormativity, Cultural Competency and Caliber of Care By Alexandra Houle-Dupont Current American healthcare and identity card policies promote a binary view of gender that is misrepresentative of the current gender spectrum. A binary view of gender is flawed, exclusionary, and discriminatory and is therefore unethical. There exist individuals who occupy spaces outside of the rigid confines of “man” and “woman”. Genderqueer individuals such as Alex Tuerk have been gaining widespread acceptance and recognition in the media yet identity card and healthcare policy only recognizes two genders. The genderqueer community deserves public recognition so as to legitimize and solidify their gender status. Furthermore, the binary promotes misconceptions about the transgender community’s use of Sex Reassignment Therapy (SRT). These misconceptions undermine transgender individuals’ status and create unnecessary barriers compatible identity cards. Moreover, these misconceptions create healthcare inequality. In order to understand the ethical implications of a binary view of gender we must first understand the intricacies and nuances in gender terminology. A person’s sex refers to an individual’s genotype (genetic makeup) and to their phenotype (observable physical appearance). The three sexes are male, female and intersex. Contrary to sex, gender identity or psychosocial sex refers to an individual’s sense of being a man, woman or anything in between. Consequently, not all men are male and not all women are female. Males that identify as women and females that identify as men are transgender. Cisgender individual’s gender identity corresponds with their native sex (ie: male men and female women). 1 Cisnormativity is the assumption and/or belief that all men are/should be male and all women are/should be female. Genderqueer individuals occupy the middle space between “man” and “woman”; they do not ascribe to the gender binary. Under the umbrella of genderqueer individuals there are those who seek gender neutrality without experiencing gender dysphoria (androgynous), those who identify as neither a man nor a woman (agender, neutrois, non-gendered, neutral-gendered, nullgender, etc.), those who alternate between two or more genders (gender fluid) and those 1 Crethar, H.C. & Vargas, L. A. (2007). Multicultural intricacies in professional counseling. In J. Gregoire & C. Jungers (Eds.), The counselor’s companion: What every beginning counselor needs to know. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. p.61. who identify as other-gendered. 2 Gender identity is highly a personal and constantly evolving. For example, in “A Gender Not Listed Here”, a 2012 survey, respondents offered gender identities such as: “birl”, “Jest me”, “skaneelog”, “twidget”, “OtherWise”, “gendertreyf”, “trannydyke genderqueer wombat fantastica”, “Best of Both”, “gender blur”, “Two-Spirit”, “genderfuck”, “rebel”, and “radical”. 3 Clearly, gender is a complex, evolving and holistic notion. Genderqueer individuals are a real gender minority and they deserve recognition. In “What’s So Bad About a Boy Who Wants to Wear a Dress?”, Ruth Padawer cites the case of Alex Tuerk. Alex has been self-proclaimed as genderqueer since the age of four, firmly stating that he is both “a boy and a girl”.4 Tuerk displays gender variant behavior: his parents describe him as “equally passionate about and identified with soccer players and princesses, superheroes and ballerinas…”.5 It is important to note that Tuerk is not transgender as he values the gendered pronouns and his native sex by asking to be referred to as “he”. Despite his use of the male pronoun, Tuerk also enjoys wearing dresses and playing with Barbie’s but does not identify as a woman: “to Alex’s irritation, people on the street often mistook him for a girl. ‘I just hate being misunderstood,’ ”.6 Tuerk feels a need to preserve a sense of fluidity in his hobbies as he enjoys activities both stereotypically associated with boys and girls: […] he is simply a boy who sometimes likes to dress and play in conventionally feminine ways. Some days at home he wears dresses, paints his fingernails and plays with dolls; other days, he roughhouses, […] rams his toys together or pretends to be Spider-Man.7 Tuerk is not alone. Padawer states that two to seven percent of boys under the age of twelve regularly display “cross-gender” behavior, with very few identifying as transgender. In February of 2011, the National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE) 2 Stringer, JAC (2009). "GenderQueer and Queer Terms". Educational Materials. Cincinnati: Midwest Trans & Queer Wellness Initiative. Retrieved 3 May 2012. And "LGBTQ Terms." Neutrois. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 July 2014. <http://neutrois.com>. 3 Harrison, Jack, Jaime Grant, and Jody L. Herman. "A Gender Not Listed Here: Genderqueers, Gender Rebels, and OtherWise in the National Transgender Discrimination Survey." Harvard Kennedy School Journal of LGBTQ Policy (2012), P. 20 4 Padawer, Ruth. "What’s So Bad About a Boy Who Wants to Wear a Dress?." New York Times. 4 Aug 2012: n. page. Print. 5 Ibid. 6 Ibid. 7 Padawer, Ruth. "What’s So Bad About a Boy Who Wants to Wear a Dress?." New York Times. 4 Aug 2012: n. page. Print. paired up with the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force to survey transgender and genderqueer individuals. The resulting report entitled “Injustice At Every Turn: A Report on the National Transgender Discrimination Survey” is largely considered the most comprehensive analysis of transgender and genderqueer issues.8 Of the 6,450 respondents 13% reported being genderqueer. The binary denies recognition to people like Tuerk who are simply asking to be understood and treated with dignity. Tuerk is misidentified and uncomfortably questioned about his gender on a daily basis. This poking and prodding at his identity stems from a lack of education, an issue easily remedied by formal recognition on the part of our government. A binary view of gender creates unnecessary barriers for genderqueer as, unfortunately, a lack of awareness leads to intolerance and discrimination. “A Gender Not Listed Here”, a study of 860 genderqueer respondents, found that 76% of genderqueer respondents were unemployed, 32% suffered physical assaults, and 31% experience harassment by law enforcement. Genderqueer females who participated experienced harassment in K-12 schools at a rate of 83% and sexual assault at 16%. These same individuals reported having attempted suicide at a rate of 43% (as compared to 1.6% for the general population) while 31% experienced police harassment and 25% reported being “very uncomfortable” seeking police assistance. 9 Clearly, genderqueer have legitimate reason to fear public assistance and have unfortunate, but justified reactions to their dire situations. I was at first verbally assaulted and then physically assaulted in broad daylight on a crowded street. As a result of the assault I didn’t leave my house for several weeks unless it was absolutely necessary (due to mental anguish). I didn’t report the incident but I have since helped start a selfdefense class for trans-men and masculine-identified genderqueers.10 Genderqueer discrimination has trickled down into healthcare settings. Two anonymous respondents in the “Injustice at Every Turn” survey reported: 8 Ibid. P. 135 McIntosh, John L. 2004. Suicide data page: 2002. Prepared for the American Association of Suicidology. Compiled from Kochanek, K.D. et al. 2004. Deaths: Final data for 2002. National Vital Statistics Reports 53(5). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. ; Harrison, Jack, Jaime Grant, and Jody L. Herman. "A Gender Not Listed Here: Genderqueers, Gender Rebels, and OtherWise in the National Transgender Discrimination Survey." Harvard Kennedy School Journal of LGBTQ Policy (2012), P. 21 10 Grant, Jaime M., et al. Injustice at every turn: a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (2011). P. 135 9 I rarely tell doctors of my gender identity. It just seems so hard to explain what “genderqueer” means in a short doctor’s appointment. I also am reluctant to take the risk of discrimination; I need to be healthy more than I need to be out to my doctors. I hate making this compromise. But I’m not quite that brave yet.11 Denial of health care by doctors is the most pressing problem for me. Finding doctors that will treat, will prescribe, and will even look at you like a human being rather than a thing has been problematic. I have been denied care by doctors and major hospitals so much that I now use only urgent care physician assistants, and I never reveal my gender history.12 Unfortunately, these are not isolated cases. According to the “Injustice at Every Turn” study, only 28% of respondents being out to all their medical providers. According to “A Gender Not Listed Here”, the 860 participants experienced medical refusal at a rate of 14% and as a result forwent needed medical care at a rate of 36%.13 Twenty-three percent of those “out or mostly out to” their medical providers were denied care and 15% who were “not out or partly out” that were also denied service. Shockingly, the gravity of the situation supersedes refusal of care. Harassment by an EMT or in an ambulance was experienced by 8% of those who were “out or mostly out” and by 5% of those who were “not out of partly out”. Moreover, 2% of those who were “out or mostly out and 1% of those who were “not out or partly out” were physically attacked and/or assaulted in a hospital. Clearly, genderqueer individuals are avoiding healthcare settings for legitimate reasons as a result of unnecessary circumstances. In theory, a binary view of gender recognizes transgender individuals as they, in the words of Alex Tuerks’s father, “preserve the traditional binary gender division: born in one and belonging in the other”. 14 A binary view of gender combined with a cisnormativity, however, has limited the understanding of transgender gender identity and given rise to discrimination. The current American healthcare system and identity card policy promote cisnormativity and a binary view of gender. We fundamentally believe that one is either entirely a man or entirely a woman. Thus, Sex Reassignment Therapy (SRT) or “gender-confirming therapy” is seen as essential to transgender individuals. If 11 Ibid. P. 75 Ibid. 13 Harrison, Jack, Jaime Grant, and Jody L. Herman. "A Gender Not Listed Here: Genderqueers, Gender Rebels, and OtherWise in the National Transgender Discrimination Survey." Harvard Kennedy School Journal of LGBTQ Policy (2012), P. 21 14 Padawer, Ruth. "What’s So Bad About a Boy Who Wants to Wear a Dress?." New York Times. 4 Aug 2012: n. page. Print. 12 you identify as a woman, then your whole body should be female, right?15 Wrong. A binary view of gender promotes the fallacy that all transgender individuals undergo all stages of SRT. The reality is that most transgender individuals value some aspects of their native sex and body. In fact, according to the “Injustice at Every Turn” survey, only 2% of transgender men and 20% of transgender women undergo SRT. Furthermore, genital reconstructive surgeries are performed on less than one in five transwomen and less than one in twenty transmen. In fact, as of 2012 only six identified surgeons in the United States performed genital reconstructive surgery. 16 Most transgender individuals simply undergo hormone therapy. According to the same study, 62% of respondents have had hormone therapy and 23% of respondents said they hope to have it in the future. 17 Through cisnormative eyes very few transpeople have truly and authentically transitioned genders. The aforementioned misconception has grave consequences when it comes to identity card policy. Gender is perceived as essential to classification; “M” and “F” boxes are included on almost every identification document (passports, birth certificates, driver’s licenses, etc.) even when it is not necessary. Policies regarding changing one’s gender on identity cards vary highly from institution to institution while certain institutions do not even recognize gender change as a possibility. In “Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of the Law”, Dean Spade points out the situation for transgender individuals in New York in the late nineties. Spade highlights how, on one hand, changes to birth certificates and to social security cards require SRT while, on the other hand, changes to driver’s licenses only require a doctor’s letter. Unfortunately the situation is even less regulated when it comes to official name changes and Medicaid, as neither have official policies regarding sex changes. In these cases, the decision is left to a clerk who might have little to no knowledge of gender identity.18 On a national level the situation has not improved significantly since the late 15 Stroumsa, Daphna. "The State of Transgender Health Care." American Journal of Public Health 104.3 (2014): 1-14. Medscape. Web. 23 July 2014. P. 2 16 Ibid. P. 4 17 Grant, Jaime M., et al. Injustice at every turn: a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (2011). 18 Spade, Dean. Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, And The Limits of Law. Brooklyn, NY: South End Press, 2011. P. 140 nineties. There are currently sixteen states whose Department of Motor Vehicles or DMV policies still require SRT to change sex (Alabama, Alaska, Georgia, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Virginia, and Wyoming) while ten other states have yet to write policies on the issue (Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Minnesota, Mississippi, North Dakota, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas). 19 In the aforementioned “Injustice At Every Turn” study, Grant, Mottet and Tanis studied, amongst other things, the percentages of transgender people unable to change gender on important identification documents. Statistics indicate that 41% were unable to update driver’s licenses, whereas the numbers were 51% for Social Security records and 74% for birth certificates. Only 21% have been able to change their gender on all of their documents with 33% having not updated any identity documents or records. 20 Clearly, gender change polices are inconsistent and this inconsistence reflects the lack of awareness and lack of respect for genderqueer rights. Imagine you are a MTF transwoman living in Kansas who has recently transitioned only using hormone therapy. One friday night you decide to go out to a nightclub with some friends. Upon arriving, the bouncer asks you for your driver’s license, the most common form of ID. Unfortunately, the DMV in Kansas does not have a policy on changing gender, so your driver’s license has an “M” on it while your cocktail dress and high heels indicate otherwise. The bouncer looks at your driver’s license and begins to fume: “What is this, a fake? Who lent it to you? Your brother?” In hushed tones you try and explain your situation, thus forcing you to reveal that you are transgender, something that you may or may not wish to keep private. As a result your privacy has been invaded, you have potentially been exposed to danger, you have been harassed and most probably embarrassed. Clearly, having documentation that is inconsistent with one’s physical appearance and/or gender identity infringes on transgender individuals’ rights. Unfortunately, such situations are all too real. In “Transgender ID Cards: Are The 'M' National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE). 2007. Driver’s license policies by state. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality 20 Grant, Jaime M., et al. Injustice at every turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (2011). 19 And 'F' Outdated?”, Lisa Leff cites the account of Chicago native and transwoman Lauren Grey: Although she had been living as a woman for months […] Grey's ID still identified her as male, puzzling the salesmen and prompting uncomfortable questions. They are like, ‘This doesn't match.’ Then you have to go into the story: ‘I was born male, but now I'm not,’ ” said Grey, 38, […] "And they are like, `What does that mean?' It was super embarrassing." Similarly awkward conversations ensued when she tried to rent an apartment, went to bars or was taken out of airport security lines for inspection. 21 Unfortunately, Ms. Grey is fortunate in comparison with her peers. According to the “Injustice At Every Turn” study, when transgender individuals presented ID that did not match their gender identity and/or appearance 40% were harassed, 15% were asked to leave the venue and 3% were attacked or assaulted.22 Transgender individuals’ privacy is constantly violated as they are forced to reveal their trans identity when completing daily tasks. In order to lead regular lives, transgender individuals must subject themselves to humiliating situations. Transgender individuals have the right to choose the extent of information they want to reveal. Transmen and transwomen should have the right to decide which people know of their native sex, which people see them for their desired gender, and which people know they are transgender. The right to autonomy is a fundamental bioethical pillar as it allows individuals to make choices without being coerced.23 As previously stated, few transgender individuals feel the need to undergo complete SRT, yet sixteen states still require SRT to change gender on identity cards and ten have not even begun to acknowledge the possibility of gender change. It then stands to ground that certain individuals feel coerced into undergoing SRT in order to obtain representative ID and have their cross-gender identification seen as legitimate. Moreover, inconsistent identity documents lead to humiliating and uncomfortable situations for transgender individuals that infringe on their right to privacy. Such situations essentially limit transgender people’s autonomy as they 21 Leff, Lisa. Transgender ID Cards: Are The 'M' And 'F' Outdated? . 2013. Web. Grant, Jaime M., et al. Injustice at every turn: a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (2011). 23 Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (Eds.), (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. 22 avoid situations that require identification. Gender non-conformity should not create barriers for transgender people, especially with regard to mundane tasks such as using a library card or retrieving social security information. Clearly, the status quo of identity card policy infringes on autonomy. Widespread misconceptions about the trans-community’s use of SRT have also resulted in lower standard of care for transgender people. In “Trans Man Denied Cancer Treatment; Now Feds Say It’s Illegal”, Susan Donaldson James cites the case of New Yorker Jay Kallio. Formerly Joy Kallio, Jay became a transman at the age of fifty. Stating that he accepted his native female sex Kallio decided to only undergo hormone treatment. Unfortunately, Kallio developed kidney failure, rheumatoid arthritis and, eventually, breast cancer. During a breast exam, Kallio’s physician discovered a canceroous lump. The physician, however, withheld the information from Kallio because he was shocked that Kallio’s gender identity was inconsistent with his identity documents and his body. Kallio’s physician never informed Jay of the lump and Kallio was only informed many months later by fluke from a lab technician. The doctor’s reaction delayed chemotherapy, allowing the cancer to take its toll. Kallio is not the first to experience such discrimination. According to the “Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey”, 19% of respondents reported “being refused care due to their transgender or gender non-conforming status” and 28% claimed to have experienced harassment in medical settings. Another study conducted at one of the largest transgender healthcare facilities in Massachusetts reported that 19.4% of their 2,635 participants report health discrimination. 24 As a result, 73% of transgender individuals avoid healthcare settings because of a history or fear of stigma, according to The Lambda Legal Health Care Fairness Survey (2010).25 Flagrant discrimination of this kind is a violation of the justice principle, one of the pillars of Bioethics. The status quo on identity card policy and in healthcare promotes the binary as well as cisnormativity. As a result, the status quo infringes on transgender and genderqueer individuals’ right to privacy, right to autonomy and right to a good standard 24 Reisner, Sari L. "Transgender Health Disparities: Comparing Full Cohort and Nested Matched-Pair Study Designs in a Community Health Center." LGBT Health 2 (2014) P. 3 25 Lambda Legal: When Healthcare Isn’t Caring: Lambda Legal’s Survey on Discrimination Against LGBT People and People Living with HIV 2010. Available at www.lambda legal.org/publications/when-healthcare-isnt-caring (last accessed November 6, 2013). of care. The World Health Organization identified the eradication of discrimination and prejudice related to sexual minorities as a key strategy needed for the promotion of sexual health worldwide. 26 First, we should federally mandate that all states have a policy regarding changing gender on all forms of ID cards and gender change should only require a doctor’s letter. This sole requirement for gender change is viable and is working in other parts of the world. In Ontario, for example, a ruling passed on April 11th, 2012 by the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario deemed that requiring proof of SRT was discriminatory and that such a requirement reinforced transgender stereotypes.27 A physician’s letter is only needed letter to testify that the individual has in fact experienced cross-gender identification. Second, as per Shukla’s recommendation, we should add a genderqueer option and a “fill-in-the-blank” option on all ID cards for individuals who do not fit into the binary.28 By instituting such options on identity cards and surveys, we would force individuals to confront and accept genderqueer individuals; this would show to the greater American public that discriminating or harassing gender minorities is unacceptable. A policy of this nature would give greater respect to genderqueer individuals and be a stepping-stone towards reducing stigma surrounding gender non-conformism. Works Cited 26 Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organi- zation: Promotion of sexual health: Recommendations for action. Proceedings of a Regional Consultation, May 19– 22, 2000, Antigua, Guatemala. 27 Anonymous "Legal sex change doesn't require surgery, tribunal says." CBC News Toronto. CBC News, 19 Apr 2012. 28 Shukla, Vipul et al. "Barriers to Healthcare in the Transgender Community: A Case Report." LGBT Health 2 (2014): P. 3 1. Cahill, Sean, and Harvey Makadon. "Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Data Collection in Clinical Settings and in Electronic Health Records: A Key to Ending LGBT Health Disparities."LGBT Health 1.1 (2014): 34-43. Print. 2. Crethar, H.C. & Vargas, L. A. (2007). Multicultural intricacies in professional counseling. In J. Gregoire & C. Jungers (Eds.), The counselor’s companion: What every beginning counselor needs to know. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum 3. Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (Eds.), (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. 4. Ellis, Sarah Kate. End Healthcare Discrimination for Transgender People. GLAAD. N.p., n.d. Web. 25 July 2014. <http://www.glaad.org/healthcare>. 5. Grant, Jaime M., et al. Injustice at every turn: a report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (2011). 6. Harrison, Jack, Jaime Grant, and Jody L. Herman. "A Gender Not Listed Here: Genderqueers, Gender Rebels, and OtherWise in the National Transgender Discrimination Survey." Harvard Kennedy School Journal of LGBTQ Policy (2012): 13-24. Print. 7. Healthy People 2020: US Department of Health and Human Services. Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender health: objectives. Healthy People 2020. Available at: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx? topicid=25. Accessed June 29, 2014. 8. Institute of Medicine: Institute of Medicine Committee on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Issues and Research Gaps and Opportunities. The Health of Lesbian, Gay,Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. 9. James, Susan. N.p.. Web. <http://abcnews.go.com/Health/transgender-bias-nowbanned-federal-law/story?id=16949817>. 10. JSI Research and Training Institute Inc. Access to Health Care for Transgendered Persons in Greater Boston. Boston, Mass: Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Health Access Project; 2000. 11. Lambda Legal: When Healthcare Isn’t Caring: Lambda Legal’s Survey on Discrimination Against LGBT People and People Living with HIV 2010. www.lambda legal.org/publications/when-health-care-isnt-caring (last accessed November 6, 2013). 12. Leff, Lisa. Transgender ID Cards: Are The 'M' And 'F' Outdated? . 2013. Web. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/06/15/transgender-id-cards_n_3447240.html>. 13. "Legal sex change doesn't require surgery, tribunal says." CBC News Toronto. CBC News, 19 Apr 2012. Web. 1 Jan 2014. <http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/legal-sex-change-doesn-t-require-surgerytribunal-says-1.1219942>. 14. "LGBTQ Terms." Neutrois. N.p., n.d. Web. 23 July 2014. <http://neutrois.com>. 15. Lutwak, Nancy. "Opportunity Also Knocks in the Emergency Room: Improved Emergency Department Culture Could Dramatically Impact LGBT Perceptions of Healthcare." LGBT Health 2 (2014): 1-2. Print. 16. National Center for Transgender Equality (NCTE). 2007. Driver’s license policies by state. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality (http://transequality.org/Resources/DL/DL_policies.html). 17. National Center for Transgender Equality 18. Padawer, Ruth. "What’s So Bad About a Boy Who Wants to Wear a Dress?." New York Times. 4 Aug 2012: n. page. Print. <http://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/12/magazine/whats-so-bad-about-a-boy-whowants-to-wear-a-dress.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0>. 19. Reisner, Sari L. "Transgender Health Disparities: Comparing Full Cohort and Nested Matched-Pair Study Designs in a Community Health Center." LGBT Health 2 (2014): 1-8. Print. 20. Shukla, Vipul et al. "Barriers to Healthcare in the Transgender Community: A Case Report." LGBT Health 2 (2014): 1-4. Print. 21. Spack, Norman P. Management of Transgenderism. 309. Journal of the American Medical Association, Web. http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleID=1568265&utm_source=Silvercha ir InformationSystems&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=MASTER:JAMALatestIs sueTOCNotification02/05/2013>. 22. Spade, Dean. Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, And The Limits of Law. Brooklyn, NY: South End Press, 2011. 137-150. Print. 23. Stringer, JAC (2009). "GenderQueer and Queer Terms". Educational Materials. Cincinnati: Midwest Trans & Queer Wellness Initiative. Retrieved 3 May 2012. 24. Stroumsa, Daphna. "The State of Transgender Health Care." American Journal of Public Health 104.3 (2014): 1-14. Medscape. Web. 23 July 2014 <http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/ 821141_print>. 25. Tobin, H. J. n. page. <http://isites.harvard.edu/icb/icb.do?keyword=k78405&pageid=icb.page414493>. 26. Transgender Law Center. Transgender Health and the Law: Identifying and Fighting Health Care Discrimination. Scribd. Scribd, July 2004. Web. 25 July 2014. <http://www.scribd.com/doc/99737410/Health-Law-Fact>. 27. Wilson, Christina et al. "Attitudes toward LGBT Patients among Students in the Health Professions: Influence of Demographics and Discipline." LGBT Heatlh 1.3 (2014): 1-8. Print.