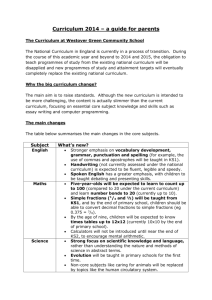

Implementing the new National Curriculum 2014

advertisement

Preface Without a change in the National Curriculum since the year 2000 the spectre of a new National Curriculum casts a dark shadow over the educational landscape becoming statutory in 2014. I know education is in a constant state of flux either through changes in the political landscape or simply because pedagogy drives our understanding of how children learn ever deeper. However a curriculum rolled out to all state schools1 is a seminal moment in the educational history of any country. A further complication would appear to be the fact that whilst the legislation’s predecessor, The Rose Review, was generally well received by the teaching profession, there are few who feel that the aims and general ethos underpinning the current documentation are either pedagogically secure or cogent in its aims. In short it would appear that schools are once again entering the stormy waters of curriculum change. This may have been welcomed if it was deemed to be a positive move forward. However, whilst most of us recognised the need for the curriculum to reflect a move into another century, most of us were hoping this would be a move forward into the 21st rather than a step back to the 19th. The key question is how we respond to this positively and continue to chart a course that provides a vibrant, creative curriculum when the tiller appears to be in the hands of an education minister described as “dangerous” by the 100 academics who wrote to the Independent newspaper earlier this year. My contention would be that schools can still continue to deliver their current curriculum even within a framework as dire as the one proposed. However the corollary to this is that each school needs to be secure in its own curriculum aims and have developed a secure pedagogy. It is only from this position that schools will be able to weave elements of the new National Curriculum into their “School Curriculum” rather than allowing one man’s quest to seemingly reinvent a Victorian education system being imposed universally on schools. This article is not intended to undertake a line by line critique of the new document but simply to provide some broad brush strokes to provoke thinking, and hopefully allay a little fear. To this end the following thoughts focus on two key subject areas; Maths (as a core subject) and History (which is generally considered to be the most contentious) and the principles drawn out from these can then be extrapolated into other curriculum subjects. 1 I am aware that academies and free schools are exempt from the National Curriculum but in reality they will still be inspected using the criteria from the document and to this end the legislation states that they should hold it in “due regard”, although I do accept that much of the argument in document is more pertinent to state schools that remain under LA control. 1 “All Change” is the familiar call of the station master as the train reaches the end of the line, and as the Curriculum 2000 enters the buffers of its educational journey there is always the danger that schools feel that the clarion call is “All Change” But I don’t believe this has to be the case. Teaching Maths post 2014 This will be my 30th year of teaching, my expertise lying predominantly in KS2. Unless my memory fails me I remember teaching subtraction to my first year 3 class all those years ago. In those days there was no National Curriculum, yet somehow I managed to teach subtraction without it. A few years later the national curriculum was introduced to officially inform me, of something that I had long suspected, that we ought to be teaching Year 3 children subtraction. This was followed by the framework in 1999 and the renewed framework in 2007 and surprise, surprise they both confirmed that I had been on the right track all along because they also proposed that children should be taught subtraction in Year 3. So one should not be too surprised to find that when we look in the new National Curriculum there it is again; Pupils should be taught to add and subtract numbers” (Consultation Document p69) In reality what has changed? The answer is the documents on the Headteachers shelves, but in reality little else. What has changed, indeed totally transformed, is the pedagogy. What I readily recognise is that I don’t teach Mathematics or any other subject for that matter the way I taught them early on in my career. However the National Curriculum is a document about coverage and does not seek to explicitly elucidate pedagogy or the style of teaching. So in terms of curriculum coverage I see there being little change. So how should we respond to the new curriculum? For me it will mirror my approach to the renewed frameworks. Many of my staff asked when we would be implementing the new document to which my reply was simply: What does it add to what we are doing already? I am a staunch supporter of the 1999 Numeracy Framework and it still forms the basis for my own planning when I teach. I saw little that the renewed framework added to it. In truth I read through the document found a few salient points that I felt would enhance our practice, presenting them to staff on half a side of A4, and then for the most part life continued as it had, because as we have alluded to schools have always taught children subtraction. But we are being forced to change There is a danger that we feel driven by the policy makers rather than by pure learning philosophy. It is true that the new curriculum puts more challenging content into lower year groups… and your point is? The new document now places division in Year 1 and adding and subtracting fractions has moved into Year 3 but my response remains the same; and your point is? What right minded teacher is going to go into a classroom tomorrow and teach calculus to their year 1 class because an office in Whitehall has decreed that it is a good idea? Is this “Quality First Teaching” where the content is allowed to drive the lesson at the expense of the needs of the child? All the research in education points towards best practice being child-centred, formatively driven by previous assessment and then highly differentiated. We are teaching 2 children, not Mathematics, and this should be reflected in classroom practice. So whilst I am aware of the changes in the document the intelligence of children does not spike because someone in a governmental office changes the wording on a curriculum document. If life was that easy any of us could effectively fulfil the role of Education Minister. In essence what changes will there be to my teaching in light of the curriculum changes? I would imagine very little if indeed anything at all. I will still enter a classroom tomorrow, teaching subtraction with a secure knowledge of the children which will remain the foundation for both my planning and my teaching. There is probably more truth in the contention that the re-writing of the standards will have an impact on the school system at a macro scale. If we are to claim that understanding the concept of division is a requirement for Year 1 then my guess is that in a few years’ time the Daily Mail will herald the scandal that… 80% of Year 1 children are falling below the standard expected for their age. Teachers will then be berated as failing and the profession will continue to be undermined in the eyes of the public but it is the goalposts that have changed not the teaching. As Einstein said, “Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid." If teaching division to a 6 year old was all that was required for them to grasp it, then how easy teaching would become, but anyone with an ounce of common sense can clearly see that this approach to “raising standards” is deeply flawed. In similar vein the removal of the levels from the national curriculum will create a “mastery” approach to the Maths curriculum. The new document focuses on “age related” expectations meaning that without levels it will be hard to use “progress made” as a viable measure. This is a major cultural shift and creates an assessment regime that is more like the driving test where the assessor only concerns themselves with whether you have attained the level that enables you to pass the test. The fact that you might have made good progress in your driving over the past year will be of little interest. This will have major ramifications for the assessment of children and also how these assessments are then used as a performance indicator for schools; however, will it change the way I teach subtraction tomorrow to the Year 3 class? I think not. So whilst I accept that there will be a change on the macro scale I see little that necessarily needs to change at the micro level of the local school, or the individual class unless of course current teaching and planning is sub-standard but there again you don’t need a national curriculum to point that out and you certainly don’t need a national curriculum to address these issues. What about the History Curriculum? When teachers get together and discuss the foibles in the new curriculum the subject they turn to first is History. The reason behind this is that it is deeply prescriptive in terms of content and there is always the danger that this drives not just “what” is taught but “how” it is taught. As a subject curriculum it is a deeply flawed piece of pedagogy on many levels and schools are right to feel like the Israelites standing by the Red Sea. In front of them are the waters of national conformity because we are all aware that the national curriculum is statutory and behind them the chariots of the Ofsted army ready to slay 3 them if they fall short of these requirements. Yet all the while they know that the document is pedagogically erroneous. How does one move forward with integrity? One of the misunderstandings of the old curriculum was how much freedom there was within it; in truth it was often schools that imposed constraints upon themselves. There has never been any requirement under the old legislation to teach any particular subject to any particular year group. It is not “illegal” to save all the Science in Key Stage 2 and teach it all in year 6. There may be a debate based around the spiral curriculum that might be worth considering but the point I am making is that the only statutory requirement is that the programmes of Study are fully covered within the key stage. In Denmark not every subject is taught every year, so whilst music is taught in year 6 it is not taught in years 7 or 8 similarly DT is not taught in years 2 or 3 but only taught in years 4 and 5. Who is to say that the Danes are not wrong in this approach? All I am saying is that we have freedom currently and we should apply this in our own schools wherever possible. So how much freedom is there in the History? The key again (like the argument relating to Maths) is for schools to be secure in what they believe is good teaching and learning in the subject and then develop schemes of work from there. As Dylan Wiliam says “pedagogy always trumps curriculum” and it is the former which should be established locally so that the national agenda weaves seamlessly into the fabric of the school rather than derailing a school’s chosen direction. If you are following a series of QCA styled units at present, looking at one of the time periods in the current breadth of study for a term then the question is does the current document allow you to continue in this cycle? At first glance the answer might appear negative but with some creative thought I see no reason why schools could not continue to deliver a curriculum based around these topics. There is a little sentence at the top of the KS2 document that could be easily lost but it states that Pupils should be taught about the ancient civilisations of Greece and Rome. The rest of the document lists a whole raft of chronological historical events but two sections stand out. One is (what we used to call) The Invaders and the other is the period of The Tudors. If you add the Stuarts to The Tudor time period and study this as one unit you are left with four topics Greeks, Romans, Invaders and the Tudors and Stuarts which can be covered across the four years of Key Stage 2. Suddenly the curriculum looks remarkably similar to that found in schools at the present time. Whilst the new curriculum has a raft of aims for each subject in the case of History the first few are not aims at all (in the truest sense of the word) they are merely a summary statement of what is achieved if you fulfil the “Subject Content” section. So ignoring those the other three aims are incredibly “history rich” and are what any decent teacher would want to see underpinning their history teaching. To be fair many of them are just a re-wording of the old programmes of study but they include; understand historical concepts such as continuity and change, cause and consequence… understand how evidence is used rigorously to make historical claims… gain historical perspective by placing their growing knowledge into different contexts… 4 So we could have a curriculum that has the Greeks in Year 3, the Romans in Year 4, the Invaders in Year 5 and the Tudors/Stuarts in Year 6 (should you wish to follow the units chronologically) all underpinned by secure historical principles such as “cause and consequence” or “fact and opinion” So what has actually changed? Precious little it would appear. Such a rolling programme with an emphasis on the quality of teaching focused on clear subject aims is what has been taught since the introduction of the first national curriculum. It is true that for complete statutory coverage you would need to fill in the gaps of the chronological mapping. However once you have taken out the time periods above, the only major remaining time period is the Middle Ages. The Stone Age could be taught as a bolt on to the Romans or the Greeks, and the Normans included in the Invaders. So what about the Middle Ages? If schools so desired they could put the Romans into the invaders and create another topic called Middle Ages that could then be taught in Year 5. Alternatively they could teach the “content” of the Middle Ages in a drip feed model in the five minutes before the register throughout the Autumn Term of Year 6. There is no prescription on the depth of study required to fulfil the “Subject Content” section. This has been the case since the Excellence and Enjoyment document stated that; “It is up to schools which aspects of the curriculum they do in depth – some they might cover in an afternoon” If this is the case then why not teach the “key developments in the reign of Henry II, including the murder of Thomas Becket” on a daily basis in bite size pieces, or as Excellence and Enjoyment suggested and cover it in an afternoon. The key is that the school is aware of what history offers to children in terms of the richness of thinking skills and that these are taught in quality units of work throughout Key Stage 2 There are some who decry the fact that the Second World War and The Victorians have been removed from the curriculum. This is frustrating especially when schools have invested much time and money in developing a bank of resources, but in truth there is no pedagogical reason why these time periods are more important than any other. If we intrinsically believe so we are in danger of falling into the same trap as the minister himself and focusing on the shallow debate on content rather than the focussing on secure History teaching which develops through a progression of skills whatever the content. As Mick Waters said from his time at QCA many of the discussions relating to which time periods children might explore sounded more like a “Battle Raffle” than a debate about pedagogy, with certain battles simply kept in the curriculum because we won them! There remains the issue of chronology which needs to be resolved. The document is a little ambiguous in its statement that; Pupils should be taught the following chronology of British history sequentially. It remains to be seen therefore whether the topics need to be tackled in a sequential order through the Key Stage. I am sure this will be clarified but I am also sure that in future years we will not hear of schools going into “notice to improve” based solely on the fact that they did not teach the history topics in the right order!2 2 See Addendum for updates from the final draft of the History Curriculum 5 What about the other foibles? Having said all the above, I am not saying that it is easy to work with a national rationale that is flawed and incoherent, it just requires schools to think a little more creatively to maintain a curriculum they feel delivers quality learning at a local level. As a school with a link in Tanzania I bemoan the fact that Africa has been taken out of the Key Stage 2 subject content. It seems a little incongruous that at the same time as the British Council (a government funded organisation) is providing grants to link schools with developing countries the new curriculum has removed these countries from the programmes of study. Again it just means that we need to find a local solution to a national problem. Aware that the government is encouraging schools to develop their own “school curriculum” we believe that in the white, middle-class confines of Malvern a good case could be made for developing strong links with an African school. Therefore we intend to teach the Geography of Africa to ensure that children here to not imbibe a narrow ethnic view of the world. We will then use the aims from the new national curriculum document to teach the subject in an African context. With the aims covered we will then drip feed children some “subject content” on the country of Canada as the national curriculum requires. In truth I lived in Canada and it is not uncommon for me to share aspects of life from that country based on my own experience both in lessons and assemblies. The paradox of innovation and accountability If all of the above appears a little Machiavellian it is not intended to be. This is not subversion for the sake of it but a desire for the profession that understands teaching and learning to take ownership of what is taught in their schools. When George Tomlinson (minister for education in the 1940’s) famously said “The minister knows nowt about education” he was quite right. Whilst politicians can have their best stab at what they think children need in the 24,000 schools across the UK with their diverse social, cultural and economic mix, the reality is that it is the local school that will provide the best solutions. Ofsted acknowledged as much in their report on Outstanding Schools saying; “Outstanding schools are confident organisations that weigh up curriculum initiatives and local and national programmes before deciding whether they are right for the school, not being afraid to dispense with them if they are not” (20 Outstanding primary Schools OFSTED 2009) The truth is that we have a National Curriculum at present and when we review the national situation we find schools that have adopted and adapted it to produce an inspirational entitlement at a local level one that engages children and delivers outstanding standards across the breadth of the curriculum. At the same time the school down the road whilst claiming to follow the same national document subjects its children to a series of dry, uninspiring lessons that lack the joined up thinking required to deliver a powerfully cohesive curriculum. The point is that a document written by a minister in an office in Whitehall has never been proven to be the key factor in determining the quality of schooling provided at a local level. This has always been down to the ethos of the school, the philosophy of the head, the creativity of the curriculum and the quality of the teachers delivering it and as far as I can see 6 these factors will remain the foundation upon which good schools will be built both before September 2014 and for many a year after. Running alongside the national curriculum on a somewhat parallel track, and seemingly at odds at times with the overbearing accountability machine that appears to drive the DfE, is the mantra that schools develop best when they take ownership of the curriculum themselves. The Ofsted quote above is one of the most recent examples but the Excellence and Enjoyment document quoted earlier said; “teachers already have great freedoms to exercise their professional judgment about how they teach… and the government supports that” In similar vein the White Paper in 2005 stated that “schools are most effective when they have the autonomy to innovate and adapt to their local circumstances”. In a speech in 2010 Michael Gove himself conceded that; “The government is genuinely committed to giving schools greater freedoms. We trust teachers and headteachers to run their schools. We think headteachers know how to run their schools better than bureaucrats or politicians.” How one quite squares this rhetoric with the seemingly heavy prescription found in many of the directives coming out of national government is the challenge facing all schools at the present time. However we must keep faith in our own ability to know what is best for the children in our own schools and design a curriculum accordingly. In this sense we need to meld the national curriculum around the school curriculum rather than the other way round. Or in the (somewhat parodied) words of one infamous American president; “Ask not what the national curriculum can do for you but what you can you do for the National Curriculum” Addendum 9th July 2013 Postscript to the History Curriculum Yesterday the final draft of the curriculum was published and we see some changes in the revised framework. The time periods beyond 1066 have been left out and placed into KS3. This adds further weight to the argument that to study “The Invaders” as we have always done would allow all schools to fulfil this element of the Programmes of study. There is still the option to study the Ancient Greeks as we have seen before. However the new orders state that children should study an “aspect or a theme in British History that extend the pupil’s chronology beyond 1066” Two of the aspects mentioned include Queen Victoria and The Battle of Britain. Whilst it might be true that the minister’s intention is that these be covered as discrete and isolated studies, in light of the fact that the National Curriculum is a minimal requirement there would be nothing to stop any school taking the option of studying the context around these two events and thereby studying The Victorians and The Second World War as topics themselves. So, what are we left with? We have the potential for a series of topics taught through KS2 that include The Invaders, The Ancient Greeks, The Victorians and the Second World War – but let me think, have I not seen these topics taught in Key Stage 2 classrooms somewhere before! 7