Queen Herod - mrtelfersEnglishpage

advertisement

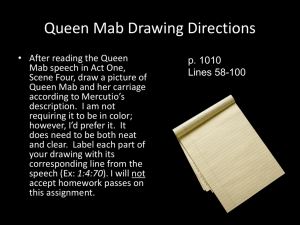

Queen Herod by Michael Woods The wife of King Herod tells of how it was she and not her husband who ordered all the newborn males to be slaughtered in order to protect her daughter form the attentions of a suitor that three visiting wise women warn her about. Duffy subverts the bible story of the Magi visiting King Herod by retelling it from his wife's point of view. She tells of three queens, not kings, visiting them. Instead of a star heralding the arrival of a saviour, it presages the birth of a man who will steal the Herods' daughter. Queen Herod does not want this to happen and so orders the slaughter of all male babies. The act of King Herod has become known as the Slaughter of the Holy Innocents but here we become aware that as far as Queen Herod is concerned, all males are potentially guilty. The order to kill babies given by the queen is undeniably shocking and discomfiting. Does the reader find it worse that a queen who has not long since given birth to a child should be capable of such action? Is it, though, consistent with the intense instinct to protect that any mother has when her child is threatened, albeit through a prophesy? Whatever the answer it is central to the poem that King Herod did not given the order. In the bible story, it was Herod's fear that the child about to be born would be greater than he would, that motivated his actions. Here, the male ego has been rejected as a source of power in favour of a woman with a strong animus. The poem opens with Queen Herod's memory of the time of year. The 'Ice in the trees' and 'furs' establishes the harsh, cold setting. The foreign queens are 'accented' and the exotic is quickly mingled with the erotic as Queen Herod notices their 'several sweating, panting breasts' (line 4). They had not followed a star as the biblical Magi did but a 'guide and boy'. The queens brought gifts in exchange for their sumptuous accommodation and opulent entertainment. There is a clear sense of affinity conveyed between them and Queen Herod. They stay up together until 'bitter dawn' (line 15) while others, including the 'drunken' Herod sleep. The dawn is 'bitter' in an inversion of its usual associations with hope since it seems that by that time of day Queen Herod has become convinced that her daughter will be under threat from the man mentioned at the end of the second verse paragraph. In bestowing gifts of Grace, Strength and Happiness we are alerted simultaneously to the fairy tale quality of the story we are being told (there are clear associations with The Sleeping Beauty) as well as the gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh offered to the infant Jesus. The black queen, though bestowing happiness as a gift seems to do so rather archly as she knows that it is unlikely to be the totality of the little girl's experience. The fact that she 'stared…Queen to Queen, with insolent lust' (lines 29-30) conveys a mixture of sadistic pleasure in knowing that her gift does not necessarily mean the same to her mother as it might to others and a sense that she is seeking a physical liaison with Queen Herod. The 'tiny starfish' made by the black Queen opening the fist of the child emphasises its vulnerability and links with the forthcoming mention of 'a new star / pierced through the night like a nail'. (lines 32-3) The image of the star being likened in a simile to a nail suggests penetration and it could be that Queen Herod senses this as a prefiguration of what might happen to her daughter. Certainly, she does not enjoy sex with Herod as she thinks of the black Queen when 'splayed…below Herod's fusty bulk'. (lines 60-61) and at that point decides not to let her daughter be taken away by a 'swaggering lad' who will 'take her name away' and give her a 'nowt in gold' in exchange. This clearly indicates that Queen Herod sees marriage as something that effaces women. The answer to Queen Herod's question 'Who?' (line 35) is a compendium of terms for a man. Even though some of these terms have potentially positive connotations, they are stripped of these to an extent through Duffy's choice of poetic technique. For example, the deliberately repetitive internal rhyme: 'The Boy Next Door. The Paramour. The Je t'adore.' (line 36) insists that men are men whatever label is attached to them. The boy next door is a well known term for a man who is fairly ordinary, a paramour is a term for an illicit lover and the French 'Je t'adore' is a phrase used by men in an attempt to make them sound sophisticated in their protestations of love. Simple alliteration reduces men to a predictable list of culturally bankrupt clichés: 'Him. The Husband. Hero. Hunk.' Other terms such as 'Adulterer. Bigamist. / The Wolf' reinforces the negativity of the presentation of men. The placing of 'Mr Right' at the end of the second verse paragraph is ironic in the light of all the wrong that men are shown to do. Having listened to this litany Queen Herod says, 'My baby stirred'. Symbolically, the black Queen guides her breast to 'the infant's mouth'. This suggests that the only real sustenance for Queen Herod's daughter can come from her. It is at this point that she makes the powerful vow: No man, I swore, / will make her shed one tear.' (lines 46-7) For her, there is an early epiphany or showing of the shape reality is going to take for her child. The following line, 'A peacock screamed outside.' is loaded with significance. In European folklore the screech of the peacock is an omen of evil. The crowing of the cock signalled Peter's third denial of Christ and there is a clear sense here that Duffy is aligning ideas of betrayal. The man who swears fidelity will ultimately betray the woman her daughter will become just as a man who swore faithfulness to Christ betrayed him. The fourth verse paragraph presents Queen Herod as someone who can hardly believe her recent experience. The impact on the senses is stressed as she watches the entourage leave: The 'pungent camels', the 'guide's rough shout' and the 'turbaned Queen' emphasise, through empirical observation, the reality of the situation; it may have 'seemed like a dream' but it was not. The verse paragraph preceding the modulation into the three stanzas that conclude the poem introduce an atmosphere of tension, as the prophesied star is awaited by others: 'The chattering / stars shivered in a cold, black sky, nervous.' (lines 78-79) This personification emphasises the human cost of the slaughter of human children but the blasé response of Orion who had 'seen it all before' reminds us not only of a cosmos indifferent to human affairs but also that Orion himself was turned into a constellation after Artemis set a scorpion on him for attempting to rape Opis, her attendant. Another constellation, Cassiopeia is mentioned in the 'West', a direct contrast to 'The Boyfriend's Star' in the East. It is introduced through the heavily alliterated, 'blatant, brazen, buoyant…/ and blue' which encapsulates the braggadocio of the male so dreaded by Queen Herod. Cassiopeia boasted that her beauty exceeded Hera's resulting in Poseidon turning her into a constellation. There is a suggestion made here by Queen Herod, then, that for every show of male power there is an answering female equivalent. The concluding stanzas of the poem present Queen Herod speaking in the collective voice of all queens and mothers. Their primary objective seems to be to protect their 'sleeping daughters', an archetypal image of female innocence that has not yet been exposed to the sexual advances of a predatory male. The stereotype of the weak woman is subverted in the metaphor, 'We have daggers for eyes'. The sinister rhyme with 'lullabies' serves as a warning and reminder that it is not only kings who are capable of command. Women are also able to unleash 'the hooves of terrible horses' that 'thunder and drum'. Despite the empowerment of women presented in the poem it is notable that men are needed to carry out the killing. It could be argued, though, that this is the ultimate weapon wielded by Queen Herod. From a feminist perspective, men destroying men saves women a lot of trouble. Historically, no one thinks of Herod's wife and this is, of course, the point Duffy is at pains to make. The gold ring offered by a man is in the shape of a zero, although this is traditionally held to symbolise eternity. The poet fuses these ideas to reinforce the unremitting nullity that is forced upon many women when they are required to take a man's name in place of their own. In fact, the central theme of The World's Wife is encapsulated in this critique upon male arrogance. It is this thought that incenses Queen Herod sufficiently to order the deaths of 'each mother's son' (l.76). In this context, the motivation of the woman is more understandable than that of the king who was outraged at the thought that a child born in a stable could be greater than he was. This poem employs a complexity of mythical elements and motivation. Is Queen Herod any more justified than her husband in giving the order for male children to be killed? If women are equally able to wield power should they not also be the agents of its application? Is Queen Herod so self-centred that she is willing to cause grief for countless other mothers, only having selfish, possessive motives for her actions behind the mask of protecting her child? The use of extended verse paragraphs is well suited to the narrative quality of the poem and its informal tone. The final three stanzas signal a shift from narrative to assertion and the vagaries of prophecy are clearly replaced by focused control. Notes King Herod: a well-known figure in the Bible. He ordered the slaughter of the Holy Innocents after learning of the birth of Jesus from the Magi, or three wise men.