File - Ossett History

advertisement

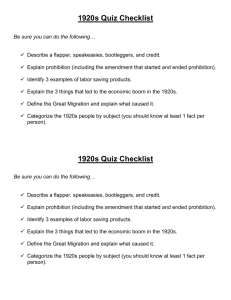

USA 1917 – 1941 – Prohibition study Guide What is Prohibition? The ratification of the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which banned the manufacture, transportation and sale of intoxicating liquors, ushered in a period in American history known as Prohibition. The result of a widespread temperance movement during the first decade of the 20th century, Prohibition was difficult to enforce, despite the passage of companion legislation known as the Volstead Act. The increase of the illegal production and sale of liquor (known as "bootlegging"), the proliferation of speakeasies (illegal drinking spots) and the accompanying rise in gang violence and other crimes led to waning support for Prohibition by the end of the 1920s. In early 1933, Congress adopted a resolution proposing a 21st Amendment to the Constitution that would repeal the 18th. It was ratified by the end of that year, bringing the Prohibition era to a close. The Prohibition Era in the United States has a storied past beginning with various temperance movements in the 1830's and finally culminating with the passage of the 18th amendment. However, the success was short-lived and the 18th amendment was repealed thirteen years later with the passage of the 21st amendment. 1830's - Temperance Movements begin advocating for abstinence from alcohol. 1847 - The first prohibition law is passed in Maine (although a prohibition law had previously passed in the Oregon territory). 1855 - 13 states have enacted prohibition legislation. 1869 - The National Prohibition Party is founded. 1881 - Kansas is the first state to have prohibition in its state constitution. 1890 - The National Prohibition Party elects its first member of the House of Representatives. 1893 - The Anti-Saloon League is formed. 1917 - The US Senate passes the Volstead Act on December 18th which is one of the significant steps to the passage of the 18th amendment. 1918 - The War Time Prohibition Act is passed to save grain for the war effort during World War I. 1919 - On October 28th the Volstead Act passes the US Congress and establishes the enforcement of prohibition. 1919 - On January 29th, the 18th amendment is ratified by 36 states and goes into effect on the federal level. 1920's - The rise of bootleggers such as Al Capone in Chicago highlight the darker side of prohibition. 1929 - Elliot Ness begins in earnest to tackle violators of prohibition and Al Capone's gang in Chicago. 1932 - On August 11th, Herbert Hoover gave an acceptance speech for the Republican presidential nomination for president in which he discussed the ills of prohibition and the need for its end. 1933 - On March 23rd, Franklin D. Roosevelt signs the Cullen-Harrison Act which legalizes the manufacture and sale of certain alcohol. 1933 - On December 5th, prohibition is repealed with the 21st amendment. Timeline task Draw a timeline of events. Add any more that you think are significant. Pick 5 most significant events and explain them. Can you add any of these key dates into your essay? Prohibition Fast Facts 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. So convinced were they that alcohol was the cause of virtually all crime that, on the eve of Prohibition (1920-1933), some towns actually sold their jails. During Prohibition, temperance activists hired a scholar to rewrite the Bible by removing all references to alcohol beverage. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) strongly supported Prohibition and its strict enforcement. Because the temperance movement taught that alcohol was a poison, supporters insisted that school books never mention the contradictory fact that alcohol was commonly prescribed by physicians for medicinal and health purposes. Prohibitionists often advocated strong measures against those who did not comply with Prohibition. One suggested that the government distribute poisoned alcohol beverages through bootleggers (sellers of illegal alcohol) and acknowledged that several hundred thousand Americans would die as a result, but thought the cost well worth the enforcement of Prohibition. Others suggested that those who drank should be: a. hung by the tongue beneath an airplane and flown over the country b. exiled to concentration camps in the Aleutian Islands c. excluded from any and all churches d. forbidden to marry e. tortured f. branded g. whipped h. sterilized i. tattooed j. placed in bottle-shaped cages in public squares k. forced to swallow two ounces of caster oil l. executed, as well as their progeny to the fourth generation. A major prohibitionist group, the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) taught as "scientific fact" that the majority of beer drinkers die from dropsie (edema or swelling). Prohibition agents routinely broke the law themselves. They shot innocent people and regularly destroyed citizens' vehicles, homes, businesses, and other valuable property. They even illegally sank a large Canadian ship. "Bathtub gin" got its name from the fact that alcohol, glycerine and juniper juice was mixed in bottles or jugs too tall to be filled with water from a sink tap so they were commonly filled under a bathtub tap. The speakeasy got its name because one had to whisper a code word or name through a slot in a locked door to gain admittance. Prohibition led to widespread disrespect for law. New York City alone had about thirty thousand (yes, 30,000) speakeasies. And even public leaders flaunted their disregard for the law. They included the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives, who owned and operated an illegal still. Some desperate and unfortunate people during Prohibition falsely believed that the undrinkable alcohol in antifreeze could be made safe and drinkable by filtering it through a loaf of bread. It couldn't and many were seriously injured or killed as a result. xi 12. In Los Angeles, a jury that had heard a bootlegging case was itself put on trial after it drank the evidence. The jurors argued in their defence that they had simply been sampling the evidence to determine whether or not it contained alcohol, which they determined it did. However, because they consumed the evidence, the defendant charged with bootlegging had to be acquitted. 13. When the ship, Washington, was launched, a bottle of water rather than Champagne, was ceremoniously broken across its bow. 14. Prohibition led to a boom in the cruise industry. By taking what were advertised as "cruises to nowhere," people could legally consume alcohol as soon as the ship entered international waters where they would typically cruise in circles. 15. National Prohibition not only failed to prevent the consumption of alcohol, but led to the extensive production of dangerous unregulated and untaxed alcohol, the development of organized crime, increased violence, and massive political corruption. 16. The human body produces its own supply of alcohol naturally on a continuous basis, 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Therefore, we always have alcohol in our bodies. 17. Prohibition clearly benefited some people. Notorious bootlegger Al Capone made $60,000,000...that's sixty million dollars...per year (untaxed!) while the average industrial worker earned less than $1,000 per year. 18. But not everyone benefited. By the time Prohibition was repealed, nearly 800 gangsters in the City of Chicago alone had been killed in bootleg-related shootings. And, of course, thousands of citizens were killed, blinded, or paralyzed as a result of drinking contaminated bootleg alcohol. 19. The "Father of Prohibition," Congressman Andrew J. Volstead, was defeated shortly after Prohibition was imposed. 20. Repeal occurred at 4:31 p.m. on December 5, 1933, ending 13 years, 10 months, 19 days, 17 hours and 32.5 minutes of Prohibition. "What America needs now is a drink" declared President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the end of Prohibition. 21. Although Prohibition was repealed 75 years ago, there are still hundreds of dry counties across the United States today. Prohibition summary The noble experiment of Prohibition was introduced by the 18th Amendment, which became effective in January 1920. Here are four reasons why Prohibition was introduced: National mood - when America entered the war in 1917 the national mood also turned against drinking alcohol. The Anti-Saloon League argued that drinking alcohol was damaging American society. Practical - a ban on alcohol would boost supplies of important grains such as barley. Religious - the consumption of alcohol went against God's will. Moral - many agreed that it was wrong for some Americans to enjoy alcohol while the country's young men were at war. Background information -Causes of Prohibition Why was Prohibition Introduced? The Prohibition Era began in January 16th, 1920 when United States prohibited the manufacture and sale of mostly alcohol. And there are many reasons to the beginning of the Prohibition Era. There were many pressure groups such as the Anti-Saloon Organization, that tried to persuade government and Congress to pass this law (this is included in social reason). MEDICAL By that time people were started to realise that alcohol damaged our health and could affect our lives. Many American men suffered from Sclerosis, which is caused by alcohol and lung cancer from smoking cigarettes. Those people suffered badly and eventually died. Because of this, many children fought their lives without their fathers, which led to families’ financial problems. ECONOMIC Many labourers got drunk and so they could not perform the job properly. The absence from work each week was very high, therefore the company was less efficient. The company could not afford to produce the same products in the time that they should and the industrialists were not satisfied. Other people also insisted that buying beer meant that the money flew away to Germany because all of the brewers were actually located in Germany. The solution that people came up was instead of helping Germany with her economy that was to spend the large amount of money on some other necessaries. POLITICAL Many votes were won in rural areas because politicians promised to back up prohibition, which helped those politicians to win the election. SOCIAL The last point of all, which we have agreed on the most important, was that the husbands were spending their family’s saving stupidly on alcohol instead of essential items, e.g. Education. That problem led to family arguments, which eventually led to divorce. The problem pressurised women the most, therefore they set up the anti-saloon groups. Which Groups supported Prohibition? Why? Anti-Saloon League The Anti-Saloon League, the leading organization for National Prohibition in the United States, was a non-partisan political pressure group established in 1893. It was a single-issue lobbying group that had branches across the United States to work with churches in marshalling resources for the prohibition fight. Its primary base of support was among Protestant churches in rural areas and the South. Before the civil War (1861-1865) temperance groups had promoted voluntary abstinence from alcoholic beverages. That war and its aftermath had diverted national attention to other matters and the movement fell into abeyance. Moral suasion had proved to be both difficult and frustrating. Following the Civil War, temperance groups increasing called for the power of the state to be used to prohibit the legal production and consumption of beverage alcohol. Combined with the frustrations of moral suasion, the country was undergoing rapid industrialization and urbanization with serious social problems of crime, poverty and disease. The cities were increasingly populated by Catholic immigrants from southern and eastern Europe. The temperance movement has been viewed by some scholars as part of a cultural war between the largely Protestant rural residents from northern Europe and the newer and culturally different immigrants. The Anti-Saloon League saw itself as primarily and fundamentally a (Protestant) church movement. In the words of leader Ernest Cherrington it was "the united Church Militant engaged in the overthrow of the liquor traffic." It promoted "Saloon Field Days," by which churches presented an appeal for contributions to the Anti-Saloon League at during at least one regular Sunday service each year. The League also used churches more directly to achieve its objectives. For example, it arranged for pastors in over 2,000 churches in Illinois to discuss a pending temperance measure and urge congregations to ask their representatives to support it. Its leaders insisted that the League was not simply another temperance organization and was not in competition with them. Rather, it was a league of temperance organizations and a clearinghouse for them. The primary purpose of the Anti-Saloon League was to unify and focus anti-alcohol sentiment effectively to achieve results. Although idealistic in its goal, it was pragmatic in its action. A secondary goal was to increase anti-alcohol sentiment. To that end it established the American Issue Publishing Company. The printing presses of the American Issue Publishing Company operated 24 hours a day and employed 200 people. Within the first three years of its existence, the publishing house was producing about 250,000,000 (one-quarter billion) book pages per month. Its superintendent, Ernest Cherrington, reported that if all the pages it printed over a twenty year period were placed end-to-end, they would circle the earth 80 times. Unlike the Prohibition Party, the Anti-Saloon League was non-partisan; unlike the Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), it did not discriminate against men; unlike democratic organizations, it operated from the top down; and unlike the Ku Klux Klan, it did not engage in the enforcement of prohibition laws. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) was a major supporter of Prohibition. The Anti-Saloon stressed its religious character and since it acted as an agent of the churches and therefore was working for God, anything it did was seen as moral and justified because it was working to bring about the Lord's will: It didn't necessarily include the outright purchase of a politician, nor did it preclude such a buy if the situation warranted. In general, however, and briefly, it consisted of swarming into a contested area and bringing every imaginable sort of pressure to bear upon the candidates and officeholders; in saturating the country with speakers and literature; in laying down a barrage of abuse, insinuation, innuendo, half-truths, and plain lies against an opponent; and in maintaining an efficient espionage system which could obtain reliable knowledge of the enemy's plans. In the minds of many leaders of the Anti-Saloon League, achieving prohibition justified many highly questionable actions. After Purley Baker assumed leadership of the League he raised large sums of money to create a major information campaign. The primary thrust of his campaign was to demonize the producers of alcoholic beverages. Most brewers were of German extraction and Baker contended that Germans "eat like gluttons and drink like swine." League posters vilified the "Huns" who were portrayed as ape-like Neanderthals threatening the U.S. and its way of life. Stigmatizing German brewers proved to be a highly successful strategy as World War I approached. When the U.S. entered the war, Anti-Saloon League leader William H. Anderson equated the dry crusade as synonymous with patriotism. Under his direction, the League insisted that "The challenge to loyal patriots of America today is to demand the absolute prohibition of the liquor traffic." The New York Times expressed concern over Anderson's unwavering dogmatism and bigotry. One pamphlet attacked "the un-American, pro-German, crime-producing, food-wasting, youth-corrupting, home-wrecking , treasonable liquor traffic" and asked "How can any loyal citizen, be he wet or dry, help or vote for a trade that is aiding a pro-German Alliance?" Another insisted that "Everything in this country that is pro-German is anti-American. Everything that is pro-German must go." Anderson attributed resistance to Prohibition in New York City to "...unwashed and wild-eyed foreigners who have no comprehension of the spirit of America." He attacked Jews, Irish, Italians and others whose cultures generally included the consumption of alcohol. However, Catholics became a special target of Anderson's bigotry. He accused the Catholic Church of mounting an "assault on law and order" and said Catholic leaders were "indignant over what they consider a Protestant victory." Therefore, Anderson said, the Church was engaged in "efforts to destroy [the Prohibition] victory and bring back the saloons." A Catholic newspaper argued that the New York Anti-Saloon League, under Anderson, had supplanted the Ku Klux Klan as the leading anti-Catholic organization in the state. For his part, Anderson said that the resurgence of the KKK was a natural and welcome response to Catholic opposition to Prohibition and "the aggression of these wet anti-Protestant forces." In 1924, Anderson was accused of embezzling money from the Anti-Saloon League and convicted of forgery for which he was sentenced to two years imprisonment in the maximum security penitentiary at Sing Sing. The Legislative Superintendent of the Anti-Saloon League was Bishop James Cannon, Jr. who hated Catholicism almost as much as alcohol and called it "The mother of ignorance, superstition, intolerance, and sin." During the presidential campaign between Catholic Al Smith and Protestant Herbert Hoover, Cannon "launched extremely personal attacks on Smith that shocked even many seasoned political observers. "Bishop Cannon also used blatant bigotry. He told voters that Smith wanted …the Italians, the Sicilians, the Poles, and Russian Jews. That kind has given us a stomach ache. We have been unable to assimilate such people in our national life, so we shut the door on them. But Smith says ‘give me that kind of people.' He wants the kind of dirty people you find today on the sidewalks of New York. Bishop Cannon's reputation and power were destroyed after he was charged with numerous crimes in both civil and church courts. He illegally used church funds to support a political candidate, engaged in shady or illegal stock market manipulations with a corrupt firm, illegally hoarded flour during World War I which he sold at great profit, embezzled a substantial fortune, and had a sexual affair with his secretary while his wife was still alive. These revelations destroyed the reputation and influence of this once powerful dry leader. Leader William E. ("Pussyfoot") Johnson developed some of the tactics used by the AntiSaloon League. For example, he wrote to wet leaders, claiming to be a brewer and asked them for advice on how to defeat temperance activists. He then published the incriminating letters he received. "Pussyfoot" Johnson seemed proud of his dishonesty. "Did I ever lie to promote prohibition? Decidedly yes. I have told enough lies for the cause to make Ananias ashamed of himself" he wrote in an article titled "I had to lie, bribe and drink to put over prohibition in America." (Ananias was a notorious liar in the New Testament.) Wayne B. Wheeler was the highly talented and skillful de facto leader of the ASL for decades. According to his biographer, he often bragged about the many deceptions he used in promoting Prohibition. With the formidable machinery and well-known intimidation tactics of the League backing him, Wheeler became very powerful: Wayne B. Wheeler controlled six congresses, dictated to two presidents of the United States, directed legislation in most of the States of the Union, picked the candidates for the more important elective and federal offices, held the balance of power in both Republican and Democratic parties, distributed more patronage than any dozen other men, supervised a federal bureau from outside without official authority, and was recognized by friends and foes alike as the most masterful and powerful single individual in the United States. By 1926, however, Wheeler was being criticized and investigated by members of Congress who were questioning the legality of the League's spending in some congressional races; he retired shortly thereafter. The League was quickly losing power as the failure of National Prohibition and the massive problems it caused became painfully and increasingly apparent to the American public. Organizations calling for Repeal proliferated and grew quickly. Former supporters of Prohibition such as John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and Henry Ford came to believe that Prohibition was not only ineffective but counterproductive and publicly called for its repeal. The League fought bitterly to the very end, but the 21st Amendment repealed the prohibition experiment in 1933. In spite of Repeal, the Anti-Saloon League never really died. From 1948 until 1950 it was known as the Temperance League, from 1950 to 1964 it was called the National Temperance League; from then it has been known as the American Council on Alcohol Problems. The current name disguises its neo-prohibition and, ultimately, prohibition agenda. Although Prohibition was rejected over 75 years ago, many people and organizations today support neo-prohibition ideas and strongly defend the vestiges of Prohibition that still remain. By 1830, the average American over 15 years old consumed nearly seven gallons of pure alcohol a year – three times as much as we drink today – and alcohol abuse (primarily by men) was wreaking havoc on the lives of many, particularly in an age when women had few legal rights and were utterly dependent on their husbands for sustenance and support. The Temperance Movement The country's first serious anti-alcohol movement grew out of a fervor for reform that swept the nation in the 1830s and 1840s. Many abolitionists fighting to rid the country of slavery came to see drink as an equally great evil to be eradicated – if America were ever to be fully cleansed of sin. The temperance movement, rooted in America's Protestant churches, first urged moderation, then encouraged drinkers to help each other to resist temptation, and ultimately demanded that local, state, and national governments prohibit alcohol outright. Excerpt from "Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition" by Daniel Okrent: "THE STREETS OF San Francisco were jammed. A frenzy of cars, trucks, wagons, and every other imaginable form of conveyance crisscrossed the town and battled its steepest hills. Porches, staircase landings, and sidewalks were piled high with boxes and crates delivered on the last possible day before transporting their contents would become illegal. The next morning, the Chronicle reported that people whose beer, liquor, and wine had not arrived by midnight were left to stand in their doorways "with haggard faces and glittering eyes." Just two weeks earlier, on the last New Year's Eve before Prohibition, frantic celebrations had convulsed the city's hotels and private clubs, its neighborhood taverns and wharfside saloons. It was a spasm of desperate joy fueled, said the Chronicle, by great quantities of "bottled sunshine" liberated from "cellars, club lockers, bank vaults, safety deposit boxes and other hiding places." Now, on January 16, the sunshine was surrendering to darkness." What does this source infer? Women's Christian Temperance Union After the Civil War, as millions of immigrants – mostly from Ireland, Germany, Italy, and other European countries – crowded into the nation's burgeoning cities, they worked hard to assimilate while simultaneously retaining cherished habits and customs from their homelands. The brewing business boomed as German-American entrepreneurs scaled up production to provide the new immigrants with millions of gallons of beer. In the 1870s, inspired by the rising indignation of Methodist and Baptist clergymen, and by distraught wives and mothers whose lives had been ruined by the excesses of the saloon, thousands of women began to protest and organize politically for the cause of temperance. Their organization, the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), became a force to be reckoned with, their cause enhanced by alliance with Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and other women battling for the vote. By the late 19th century the WCTU, led by the indomitable Frances Willard, could claim some significant successes – it had lobbied for local laws restricting alcohol and created an anti-alcohol educational campaign that reached into nearly every schoolroom in the nation. Its members viewed alcohol as the underlying source of a long list of social ills and found common cause with Progressives trying to ameliorate the living conditions of immigrants crowded into squalid slums, protect the rights of young children working in mills and factories, improve public education, and secure women's rights. But the WCTU's ultimate goal, a prohibition amendment to the constitution, still seemed impossibly out of reach. It would take the emergence of a new organization, the Anti-Saloon League, for the drys' dream to enter the realm of the possible. Who opposed Prohibition? They were called the "wets" — primarily liturgical Protestants (Episcopalians, German Lutherans) and Roman Catholics, who denounced the idea that the government should define morality. The issue of Prohibition became a highly controversial one among medical professionals, because alcohol was widely prescribed by physicians of the era for therapeutic purposes. Congress held hearings on the medicinal value of beer in 1921. Subsequently, physicians across the country lobbied for the repeal of Prohibition as it applied to medicinal liquors. The Prohibition Years – The problems In 1929, however, the Wickersham Commission reported that Prohibition was not working. In February 1933, Congress passed the 21st Amendment, which repealed Prohibition. Prohibition had failed. Here are six reasons why: 1. There weren't enough Prohibition agents to enforce the law - only 1,500 in 1920. 2. The size of America's boundaries made it hard for these agents to control smuggling by bootleggers. 3. The low salary paid to the agents made it easy to bribe them. 4. Many Americans never gave their support to Prohibition and were willing to drink in speakeasies - bars that claimed to sell soft drinks, but served alcohol behind the scenes. 5. Gangsters such as Al Capone made money from organised crime. 6. Protection rackets, organised crime and gangland murders were more common during Prohibition than when alcohol could be bought legally. How did Prohibition lead to crime? Prohibition created an enormous public demand for illegal alcohol. Gang leaders such as Al Capone and Bugs Moran battled for control of Chicago's illegal drinking dens known as speakeasies. Capone claimed that he was only a businessman, but between 1927 and 1930 more than 500 gangland murders took place. The most infamous incident was the St Valentine's Day massacre in 1929 when Capone's men killed seven members of his rival Moran's gang while Capone lay innocently on a beach in Florida. Capone was imprisoned for income-tax evasion and died from syphilis in 1947. It has been estimated that during Prohibition, $2,000 million worth of business was transferred from the brewing industry and bars to bootleggers and gangsters. Enforcing Prohibition In a perfect world, once a law or constitutional amendment is passed, the resources necessary to enforce it are plentiful and effective. Prohibition, unfortunately for its supporters, was not so easily enforced. Many challenges quickly surfaced when it came time to keep demon rum from being bought, sold or imported. Gangs of illegal alcohol traffickers, comparable to today's illegal drug rings, became common. They were able to charge a steep price for sneaking alcohol into the country - and they thrived in the process. It became obvious that bootlegging had reached an all-time high when the demand for $10,000 notes reached an unprecedented level in 1926. Critics of Prohibition recognized this as a telltale sign of large transactions between bootleggers. European "rum fleets" proliferated. Small boats would sail out to ships waiting in international waters and bring back large quantities of alcohol. It was also very easy to smuggle alcohol from Canada. Political corruption reached new levels, as those who were profiting from illegal trafficking lined the pockets of crooked politicians. Illegal speakeasies flourished. Prior to Prohibition, there were fewer than 15,000 legal bars in the United States. By 1927, however, more than 30,000 speakeasies were serving illegally across the country. Approximately 100,000 people brewed alcohol illegally from home [source: Digital History]. Undercover police officers were trying to do their jobs, but the available manpower was still tiny in comparison with the thriving industry. Even when arrests were made, corruption made it nearly impossible to convict anyone. For example, during one time period more than 7,000 arrests were made in New York for alcohol violations, and only 17 of those ended in conviction. Many states eventually grew tired of the hassle. In fact, by 1925 six states had developed laws that kept police from investigating infractions. Cities in the Midwest and Northeast were particularly uninterested in enforcing Prohibition [source: Digital History]. Fiorello LaGuardia, mayor of New York City, testified before the Senate judiciary committee and had this to say about Prohibition: "It is impossible to tell whether Prohibition is a good thing or a bad thing. It has never been enforced in this country" [source: Pittsburgh PostGazette]. Actually, Prohibition Was a Success By Mark H. Moore; Mark H. Moore is professor of criminal justice at Harvard's Kennedy School of Government Published: October 16, 1989 Close analyses of the facts and their relevance is required lest policy makers fall victim to the persuasive power of false analogies and are misled into imprudent judgments. Just such a danger is posed by those who casually invoke the ''lessons of Prohibition'' to argue for the legalization of drugs. What everyone ''knows'' about Prohibition is that it was a failure. It did not eliminate drinking; it did create a black market. That in turn spawned criminal syndicates and random violence. Corruption and widespread disrespect for law were incubated and, most tellingly, Prohibition was repealed only 14 years after it was enshrined in the Constitution. The lesson drawn by commentators is that it is fruitless to allow moralists to use criminal law to control intoxicating substances. Many now say it is equally unwise to rely on the law to solve the nation's drug problem. But the conventional view of Prohibition is not supported by the facts. First, the regime created in 1919 by the 18th Amendment and the Volstead Act, which charged the Treasury Department with enforcement of the new restrictions, was far from all-embracing. The amendment prohibited the commercial manufacture and distribution of alcoholic beverages; it did not prohibit use, nor production for one's own consumption. Moreover, the provisions did not take effect until a year after passage -plenty of time for people to stockpile supplies. Second, alcohol consumption declined dramatically during Prohibition. Cirrhosis death rates for men were 29.5 per 100,000 in 1911 and 10.7 in 1929. Admissions to state mental hospitals for alcoholic psychosis declined from 10.1 per 100,000 in 1919 to 4.7 in 1928. Arrests for public drunkenness and disorderly conduct declined 50 percent between 1916 and 1922. For the population as a whole, the best estimates are that consumption of alcohol declined by 30 percent to 50 percent. Third, violent crime did not increase dramatically during Prohibition. Homicide rates rose dramatically from 1900 to 1910 but remained roughly constant during Prohibition's 14 year rule. Organized crime may have become more visible and lurid during Prohibition, but it existed before and after. Fourth, following the repeal of Prohibition, alcohol consumption increased. Today, alcohol is estimated to be the cause of more than 23,000 motor vehicle deaths and is implicated in more than half of the nation's 20,000 homicides. In contrast, drugs have not yet been persuasively linked to highway fatalities and are believed to account for 10 percent to 20 percent of homicides. Prohibition did not end alcohol use. What is remarkable, however, is that a relatively narrow political movement, relying on a relatively weak set of statutes, succeeded in reducing, by one-third, the consumption of a drug that had wide historical and popular sanction. This is not to say that society was wrong to repeal Prohibition. A democratic society may decide that recreational drinking is worth the price in traffic fatalities and other consequences. But the common claim that laws backed by morally motivated political movements cannot reduce drug use is wrong. Not only are the facts of Prohibition misunderstood, but the lessons are misapplied to the current situation. The U.S. is in the early to middle stages of a potentially widespread cocaine epidemic. If the line is held now, we can prevent new users and increasing casualties. So this is exactly not the time to be considering a liberalization of our laws on cocaine. We need a firm stand by society against cocaine use to extend and reinforce the messages that are being learned through painful personal experience and testimony. The real lesson of Prohibition is that the society can, indeed, make a dent in the consumption of drugs through laws. There is a price to be paid for such restrictions, of course. But for drugs such as heroin and cocaine, which are dangerous but currently largely unpopular, that price is small relative to the benefits. Research Task Find four points to show that prohibition was a: 1. success 2. failure Was Prohibition Really a Success? by David J. Hanson, Ph.D. “Prohibition was quite successful,” argues Rev. Mark H. Green, head of the Christian Action League of North Carolina. But specifically by what measure or measures could Prohibition be judged a success? The reverend states as fact that Prohibition reduced alcohol consumption. However, that is a very controversial assertion. Per capita consumption of alcohol increased during Prohibition, according to the federal Wickersham Commission. More specifically, it increased over 500% between 1921 and 1929, according to a study published by Columbia University Press. It’s important to point out that per capita consumption dropped dramatically between 1910 and the imposition of Prohibition in 1920. So Prohibition reversed a downward trend in alcohol consumption. The reverend also fails to note the change in the way people drank after Prohibition was implemented. The Noble Experiment drove drinking underground to speakeasies and other uncontrolled locations. Under Prohibition, people drank less often but much more heavily and quickly when they did drink. People didn’t go to an illegal speakeasy to enjoy a leisurely drink with their meal. Prohibition clearly lead to dangerous binge drinking. Prohibition promoted public health? Not so. Prohibition lead to the consumption of often unsafe bootleg alcohol containing poisonous lead compounds, embalming fluid, creosote, poisonous methyl alcohol, and other dangerous substances. Hundreds of thousands of people became ill, suffered paralysis, lost their sight, or died from illegal alcohol. Prohibition reduced crime? Not so. To the contrary, it stimulated the rapid development of organized crime. “Prohibition is a business.” observed the notorious Al Capone. “All I do is supply a public demand.” And indeed he did. After violently disposing of his competitors, Capone earned 60 million untaxed dollars each year. That was at a time when the typical industrial worker earned less than one thousand dollars annually. Crime paid very well. And it led to the corruption of the entire administrations, including the police departments, of cities across the country. The reverend then argues that denying adults age 18-20 the right to drink (that is, imposing Prohibition on adults of specific ages) has reduced alcohol problems. Not so. For example, raising the drinking age to 21 was associated with a lower rate of alcohol-related traffic fatalities among those 19-20. However, it merely postponed those fatalities, which subsequently increased among persons age 21-24. The reverend refers to Dr. John McCardell, President Emeritus of Middlebury College. That educational leader has pointed out some of the many problems caused by raising the drinking age. A major such problem is that student drinking is driven underground, where, like the speakeasies of Prohibition, it encourages binge drinking. Simultaneously, colleges are no longer able to teach responsible drinking behavior among their adult students who choose to drink. Instead, they must take the role of enforcer of a very unpopular law that’s inconsistent with American history and culture. And alcohol has always been a part of American college life. A brewery was one of Harvard College’s first building projects because it wanted to ensure a steady supply of fresh beer to the student dining hall. The reverend tries unsuccessfully to debunk the fact that moderate attitudes and laws encourage moderation. Many groups around the world have learned how to consume alcohol widely with few problems. Those familiar to most Americans include Italians, Jews, Greeks, Portuguese and Spaniards. The success of such groups has three parts: 1. beliefs about the substance of alcohol, 2. the act of drinking, and 3. education about drinking. In these successful groups: The substance of alcohol is seen as neutral. It is neither a terrible poison nor is it a magic substance that can transform people into what they would like to be. The act of drinking is seen as natural and normal. Drinking and abstention are seen as equally acceptable. While there is little or no social pressure to drink, there is absolutely no tolerance for abusive drinking. Education about alcohol starts early and starts in the home. Young people are taught -through their parents' good example and under their supervision -- that if they drink, they must do so moderately and responsibly. Indeed, federally-sponsored research has found that those who drink with their parents are less likely to drink as often or to abuse alcohol than are others. Imagine if we handled driving education the way we do drinking “education.” We would tell young people that driving is dangerous and kills tens of thousands of people each year, that driving requires physical skill, emotional maturity, knowledge of rules of the road, and practical driving experience. We would deny them the opportunity to obtain a driver learner’s permit, to practice driving, and to become skilled and safe drivers. Then, on their 21st birthday, we would hand them car keys and tell them that it’s safer to take public transportation but if they must drive, to be careful and try to avoid accidents. But that’s exactly what we do with alcohol education and we are surprised that we don’t get better results. We need to issue drinking learner permits, under strict guidelines, to promote responsible drinking behaviours among adults age 18-20. If the goal of Prohibition was to increase heavy episodic (binge) drinking, increase the consumption of dangerous illegal alcohol, reduce public health, foster violent and powerful organized crime, promote political corruption and encourage widespread disrespect for the law, then it was clearly a resounding success. The end of Prohibition The 21st Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is ratified, repealing the 18th Amendment and bringing an end to the era of national prohibition of alcohol in America. At 5:32 p.m. EST, Utah became the 36th state to ratify the amendment, achieving the requisite three-fourths majority of states' approval. Pennsylvania and Ohio had ratified it earlier in the day. The movement for the prohibition of alcohol began in the early 19th century, when Americans concerned about the adverse effects of drinking began forming temperance societies. By the late 19th century, these groups had become a powerful political force, campaigning on the state level and calling for national liquor abstinence. Several states outlawed the manufacture or sale of alcohol within their own borders. In December 1917, the 18th Amendment, prohibiting the "manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors for beverage purposes," was passed by Congress and sent to the states for ratification. On January 29, 1919, the 18th Amendment achieved the necessary threefourths majority of state ratification. Prohibition essentially began in June of that year, but the amendment did not officially take effect until January 29, 1920. In the meantime, Congress passed the Volstead Act on October 28, 1919, over President Woodrow Wilson's veto. The Volstead Act provided for the enforcement of Prohibition, including the creation of a special Prohibition unit of the Treasury Department. In its first six months, the unit destroyed thousands of illicit stills run by bootleggers. However, federal agents and police did little more than slow the flow of booze, and organized crime flourished in America. Large-scale bootleggers like Al Capone of Chicago built criminal empires out of illegal distribution efforts, and federal and state governments lost billions in tax revenue. In most urban areas, the individual consumption of alcohol was largely tolerated and drinkers gathered at "speakeasies," the Prohibition-era term for saloons. Prohibition, failing fully to enforce sobriety and costing billions, rapidly lost popular support in the early 1930s. In 1933, the 21st Amendment to the Constitution was passed and ratified, ending national Prohibition. After the repeal of the 18th Amendment, some states continued Prohibition by maintaining state wide temperance laws. Mississippi, the last dry state in the Union, ended Prohibition in 1966. As part of your research for your essay, think about the arguments and facts you would use to explain: 1. Why Prohibition was introduced, and then later repealed. 2. How successful Prohibition was. People in New York celebrate the ratification of the 21st Amendment ending Prohibition, Dec. 5, 1933 New York Times Co./Hulton Archive/Getty Images In 1932, Herbert Hoover was giving an election time speech. http://americanhistory.about.com/library/docs/blhooverspeech1932.htm Task: Read the article and pick out all the references to Prohibition. What were Herbert Hoover’s feelings towards Prohibition? How does his political ideology affect this? What was the consequence of Herbert Hoover being elected on Prohibition? The Effects of Prohibition As we mentioned, Prohibition created a vast illegal market for the production, trafficking and sale of alcohol. In turn, the economy took a major hit, thanks to lost tax revenue and legal jobs. Prohibition nearly ruined the country's brewing industry. Anheuser-Busch survived Prohibition by turning to other products, such as ice cream, root beer, malt extract and corn syrup. The city of St. Louis boasted 22 breweries before Prohibition, and a mere nine reopened after it ended. The advent of the Great Depression (1929-1939) caused a huge change in American opinion about Prohibition. Economic issues crippled the country, and it just didn't make sense to those suffering that the country couldn't profit from the legal taxation of alcohol. After all, the gangsters and bootleggers certainly seemed to benefit. Prohibition also produced some interesting statistics concerning the health of Americans. Deaths caused by cirrhosis of the liver in men dropped to 10.7 men per 100,000 from 29.5 men per 100,000 from 1911 to 1929 [source: Digital History]. On the other hand, adulterated or contaminated liquor contributed to more than 50,000 deaths and many cases of blindness and paralysis. It's pretty safe to say this wouldn't have happened in a country where liquor production was monitored and regulated [source: Digital History]. Alcohol consumption during Prohibition declined between 30 and 50 percent [source: Digital History]. Conversely, by the end of the 1920s there were more alcoholics and illegal drinking establishments than before Prohibition [source: Encyclomedia.com] SIGNIFICANCE??? Prohibition in Hollywood Al Capone died 60 years ago, but the gangster legend lives on in scores of movies, books and TV shows. "Little Caesar" was an immensely popular film about 1920s gangsters that helped spawn a heap of others. Following the movie's release in 1930, more than 50 others were put out in the next year alone. True and fictional stories from that time have yielded many other incredibly popular films, like "The Godfather," "Scarface" and "Public Enemy." And country bootleggers are often depicted as folk heroes -- think "The Dukes of Hazzard." Roaring '20s style, immortalized in F. Scott Fitzgerald's "The Great Gatsby," also has its place in TV and movie history. Hard-partying flappers -- and their short hair, fringed dresses and hip flasks -- are still glamorized today, most recently in the movie musical "Chicago." After Prohibition After Prohibition was repealed, it was left up to the states to decide how to govern alcohol consumption. Most states made 21 the legal drinking age, although a handful required drinkers to be only 18. No national drinking age existed until 1984, when the National Minimum Drinking Age Act was passed. One major catalyst behind the creation of this law was the increase in deaths related to drunk driving. The 1980s and '90s saw a major movement to decrease drunk driving -- Candy Lightner founded Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD) after a drunk driver fatally hit her daughter in 1980. Since then, alcohol-related driving fatalities have decreased substantially. In 1982, 60 percent of automobile-related fatalities involved alcohol. By 2005, that number had dropped to 39 percent [source: Alcohol Alert]. Despite the national repeal on Prohibition, hundreds of counties in the United States enforce "dry" laws. These laws typically ban the manufacture and sale but not consumption. Nearly half of Mississippi's counties are dry. In fact, it's even against the law to drive through a dry county in the state with alcohol in the car, even if you're transporting it to a personal residence. Kentucky isn't much better for alcohol lovers. Thirty counties are wet and 55 are bone-dry. The other 35 are considered "moist" -- they have some regulations but not complete prohibition. Alabama, Arkansas, Texas, Kansas and Virginia also have a large proportion of dry counties. Hundreds of dry towns (within wet counties) also exist across the country. In fact, 129 of them are in Alaska. Many, many other rules exist regulating the sale and consumption of alcohol on a local level. They often seem confusing and contradictory. One other once-common rule restricts the sale of alcohol on Sundays. This law was developed in Colonial times to honor the Christian Sabbath day in Colonial times. Famous Figures of Prohibition Dr. Benjamin Rush: Well-respected physician who was one of the first people to document opinions on the ill effects of gin, whiskey and other distilled liquors. He was a staunch advocate of “personal cleanliness.” Carrie Nation: Nation, a leader of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, was known for praying on the doorsteps of saloons, often brandishing a hatchet to scare off would-be drinkers. Her passion was fueled by a short-lived marriage to an alcoholic. She was arrested at least 30 times between 1900 and 1910 for destroying saloons with her protemperance cohorts. Fatty Arbuckle: In 1921, this famous screen actor was accused of raping an intoxicated aspiring actress who later died of peritonitis from a ruptured bladder. The theory was that he had raped her with a piece of glass or a bottle. Several trials later, Arbuckle was acquitted, but his career was largely ruined. More than a decade later, he broke back into the industry but soon died of a heart attack. The reform was introduced at the same time that President Woodrow Wilson was advocating a moralistic foreign policy. The American architects of prohibition attempted to export prohibition abroad, forming in 1919 a World League against Alcoholism. By attempting to make other countries abandon alcohol, the prohibitionists wished to safeguard the US against illegal imports of liquor, and also displayed the moral idealism of the prohibitionists, showing how their plans enmeshed with Wilsonian ideals for a new world order. The study of prohibition as a movement can be used to illuminate the missionizing theme in American foreign policy at the time of World War I. Quotes regarding Prohibition By Al Capone I make my money by supplying a public demand. If I break the law, my customers, who number hundreds of the best people in Chicago, are as guilty as I am. Everybody calls me a racketeer. I call myself a businessman. Comment in 1925 By Eleanor Roosevelt Little by little it dawned upon me that this law was not making people drink any less, but it was making hypocrites and law breakers of a great number of people. Her newspaper column, "My Day," July 14, 1939 By Rutherford B. Hayes Personally I do not resort to force — not even the force of law — to advance moral reforms. I prefer education, argument, persuasion, and above all the influence of example — of fashion. Until these resources are exhausted I would not think of force. Regarding a suggested Prohibition amendment, in his diary, 1883 Prohibition and crime – Test your knowledge 1. The main anti-alcohol group in America leading up to Prohibition was... The Anti-Drinking Group Dry America 2. Prohibition was known as... The noble experiment The brave experiment The unique experiment The Anti-Saloon League 3. Which amendment introduced Prohibition? The 17th Amendment The 18th Amendment The 19th Amendment 5. Who was the most infamous gangster of the 1920s? 4. Illegal smugglers of drink during Prohibition were known as... Cattle rustlers Bootleggers Moonshiners 6. The most notorious gangster murders were known as... Al Capone The July Crisis Bugs Moran The St Valentine's Day Massacre Bugsy Malone The November Massacre 7. What were the illegal drinking dens called? Nightclubs Drinkeasies Speakeasies 8. The enquiry into Prohibition was called the... Thompson Commision Brooks Commission Wickersham Commission 9. Prohibition helped to create... organised crime less crime a drink-free society 10. Prohibition is seen by historians as... a success a failure neither Useful resources 1. http://www.pbs.org/kenburns/prohibition/prohibition-nationwide/timeline/ 2. http://www.loc.gov/teachers/classroommaterials/presentationsandactivities/presenta tions/timeline/progress/prohib/ 3. http://americanhistory.about.com/od/prohibitionera/a/prohibition.htm 4. http://womenshistory.about.com/od/temperance/a/Temperance-Movement-AndProhibition-Timeline.htm 5. http://history.howstuffworks.com/historical-events/prohibition5.htm 6. http://www.anzasa.arts.usyd.edu.au/ahas/prohibition_overview.html Prohibition and The Progressive Movement, 1900-1920, James Timberlake, Harvard University Press, 1963 8. Profits, Power and Prohibition: Alcohol Reform and the Industrializing of America, 1800-1930, John J. Rumbarger, State University of New York Press, 1989 9. Al Capone: A Biography, Luciano Iorizzo, Greenwood Press, 2003 10. http://www.vintageperiods.com/prohibition.php 7. 11. http://www.pbs.org/kenburns/prohibition/roots-of-prohibition/ 12. http://prohibition.osu.edu/anti-saloon-league 13. http://www.wisegeek.org/what-is-the-temperance-movement.htm#slideshow 14. http://www.slideshare.net/cvkelly/prohibition-3996443 15. http://www.anzasa.arts.usyd.edu.au/ahas/… 16. http://prohibition.osu.edu/ 17. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prohibition… 18. http://history1900s.about.com/od/1920s/p… 19. http://depts.washington.edu/depress/prohibition_seattle.shtml 20. http://eh.net/encyclopedia/article/miron.prohibition.alcohol