File - CLASS 11 a

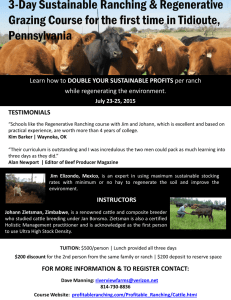

advertisement

Question Answers 1. Why is Theophil Eshley called a cattle painter by force of environment? The circumstances that forced Eshley to start painting cattle were not his genuine love for cattle but a force of the environment in which he lived. His home was in a park-like, villa-dotted semi suburban district. On one side of his house was a picturesque meadow and so many colorful, little cows ate grass there. All Eshley saw was cows, gardens, flowers, grass and walnut trees and his imagination could not WORK without cows and other cattles hence his paintings had the domination of cattle. 2. TheophilEshley didn’t have any background that directly connected him to cows and oxen. Explain. Although Eshley was a cattle painter, he had no ancestral or temperamental connections with cows and oxen. He lived in the city where he had no nearby ranch or a dairy farm. There was no atmosphere pervaded with horn and hoof, milking-stool, and branding-iron, all CHARACTERISTIC of life with cattle. His home was in a park-like, villa-dotted district. 3. What was Eshley’s first award winning work? Eshley’s first cattle painting was of two reposeful milch-cows in a setting of walnut tree and meadow-grass and filtered sunbeam. 4. The Royal Academy encourages orderly, methodical habits in its children. Explain. Eshley was a painter brought up and patronized by the Royal Academy. The academy chose to honor and keep only orderly artists like Eshley who painted stereotiped paintings. The academy was particular that every artist adopted to uniformity regarding the genre/kind of his WORK. 5. Who was Adela Pingsford? Why did she seek Eshley’s help? Adela was Eshley’s closest neighbor. The lady had no remarkable love for art or animals but she could die for plants and flowers. One fine afternoon in late autumn she knocked on the outer door of Eshley’s studio because a stray ox had wandered into her garden and she didn’t have the courage to get the huge beast out all alone. Her garden had just been put straight for the winter, and she could not even imagine an ox roaming about in it. Apart from this, she had some finest chrysanthemums just coming into flower. Besides, she was practically all alone; the housemaid was having her afternoon out and the cook was lying down with an attack of neuralgia. 6. Why was Adela disappointed at having sought help from Eshley? Adela had never known Eshley anything more than a painter. All that her instinct urged her was to go get help from her neighbor, a man, known for his paintings of cattle. She was of the opinion that Eshley could be good at chasing an ox out of her garden. With Eshley asking the panic stricken lady ‘what kind of an ox was in her garden,’ ‘from where it came into the garden’ and his foolish inquiry ‘if the ox would not go out itself,’ Adela knew that the man was going to be useless for the task at hand. 7. How did Eshley try to turn down Adela’s request? Eshley confessed that he was not at all good at chasing an ox out of a garden although he was known for his cattle paintings. He even made it clear that he painted only cows, that too, diary cows, the least dangerous ones. He said that rounding up an ox is easy in films because such stunts are either done with accessories or they are fake. 8. How do you describe the ox? The ox was a huge mottled brute, dull red about the head and shoulders, passing to dirty white on the flanks and hind-quarters, with shaggy ears and large blood-shot eyes. It bore about as much resemblance to the dainty paddock heifers that Eshley was accustomed to paint. 9. How did Eshley attempt to round the ox up? When the necessity for doing something for Adela was becoming imperative, Eshley took a step or two in the direction of the animal, clapped his hands, and made noises of the “Hish” and “Shoo” variety. The ox gave no outward indication of the fact that Eshley was asking it to leave the place. When this failed, Eshley picked up a pea-stick and flung it with some determination against the animal’s mottled flanks. 10.How did Eshley lead the ox into Adela’s morning room? Finally the ox seemed to realise that it was to go. It gave a hurried final pluck at the bed where the chrysanthemums had been, and strode swiftly up the garden. Eshley ran to head it towards the gate, but only succeeded in quickening its movement. The ox, thinking Eshley meant to lead it to the lady’s morning room, crossed the tiny strip of turf and pushed its way through the open French window into Adela’s morning-room. 11.How did the thought of painting the ox ring in Eshley’s mind? In fact it was not Eshley who first thought of painting the ox in Adela’s room – it was Adela herself who satirically suggested this. When Eshley said that he was not responsible for the ox’s entry into the morning room, Adela retorted that his foolish whims would think of painting the scene. Although Adela didn’t the least mean this, Eshley considered it an amazing idea. 12.The episode was the turning-point in Eshley’s artistic career. Which episode? How was it a turning point? Eshley’s remarkable picture, “Ox in a morning-room, late autumn,” was one of the sensations and successes of the next Paris Salon, and when it was subsequently exhibited at Munich it was bought by the Bavarian Government, in the teeth of the spirited bidding of three meat-extract firms. From that moment his success was continuous and assured, and the Royal Academy was thankful, two years later, to give a conspicuous position on its walls to his large canvas “Barbary Apes Wrecking a Boudoir.” 13.What did Eshley present Adela? Eshley presented Adela Pingsford with a new copy of “Israel Kalisch,” and a couple of finely flowering plants of Madame AdnréBlusset. 14.Elaborate on the use of humor by Saki with special reference to Stalled Ox. Saki’s Stalled Ox is a non-stop, humor-packed story. From the chancepainter TheophilEshley, his neighbour Adela to the Ox, all characters make the reader laugh at once or reserve laughter for another time. The circumstances the led to the making of a cattle-painter out of Eshley may not be as such funny but the episode of Eshley chasing the ox out with peasticks, Adela’s rising rage at the sight of the cattle expert’s leading the ox’s way into her parlour, his painting the ox in his neighbor’s parlour, etc. are Saki’s wonderful contribution to humor and literature. Adela’s replies are rude but when they are weighed against Eshley’s absent minded queries, the reader joins Adela for her support because such questions as those Eshley asked are not only irrelevant, they are foolish. Eshley’s asking, “won’t it go?” is another reason for laughter because his question was quite childish. Apart from Eshley’s kind of questions, Adela’s helplessness adds fun to the story although the reader feels like the helpless neighbor. Eshley’s remark, “it’s eating a chrysanthemum,” and the desperate response on Edla’s side evoke myrth and anger in the reader. The author has been able to present an artist under utmost thoughtlessness with a huge ox eating a plant-lover’s most expensive flowers one by one. Adela says, “you ‘shoo’ beautifully,” and the painter goes on shooing without registering her sarcasm. Her making a note that the ox was eating a Mademoiselle Louise Bichot in icy calm can be understood as an expression of maximum rage. Eshley’s failure to get a grasp of the lady’s sarcasm leads him to telling her that the ox was an Ayrshire ox. It is extraordinarily ironical that the ox was a degree more sensible than the artist, for, it was able to understand what the artist and the lady were trying to communicate with it. This follows another instance of laughter – Eshley leads the ox into the lady’s morning room! The way the author narrates the ox’s mistaken movement is humorous and hilarious. Finally there is this artist who runs to his house to bring his painting implements just because he failed to read Adela’s sarcasm and this appears more than humor.