Hale-Meyers

advertisement

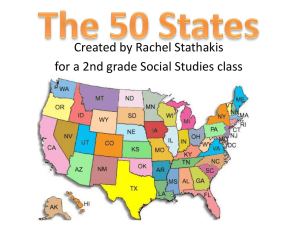

Chelsea Hale Amanda Meyers ENGL 401 – Vieira Final Research Project “Divided by Dialect: Discrimination at UIUC based on northern and southern Illinois Dialects” Both English majors with a minor in Secondary Education, we have been around one another for quite some time. Between the different classes we have taken as well as the various projects we have worked on together, we have come to know each other very well. Although typically something overlooked when we interact with one another, one major difference between the two of us is our accent; while Amanda is from northern Illinois, Chelsea is from southern Illinois. We used this difference as a starting point for our research and decided to focus on the following question: “Do students with a southern/northern Illinois ‘dialect’ experience linguistic discrimination at UIUC? Do people from southern/northern Illinois perpetuate this discrimination?” We believe that discrimination based on differing Illinois dialects does occur at the University of Illinois, and that people from both southern and northern Illinois enable this discrimination. Researchers such as Jennifer Cramer, Glasper Curtshone, Robel Belay, Alana Mbanza, and Joseph M. Williams have focused on issues such as dialect stereotyping and the certain linguistic ways people coupe with being stereotyped against. For our purposes, we are defining dialect as the speech patterns that emerge from two regions in Illinois: northern and southern. Like the researchers mentioned above, we will be comparing and contrasting the dialects between the different regions; however, we move past just the geographical differences and into the dialect’s affect on the social, mental, and academic experiences at UIUC. 1 Analysis In order to obtain information regarding the perceptions of dialect at the University of Illinois, we interviewed seven people - four were associated with northern Illinois and three were associated with southern Illinois. In the following sections, their personal stories and views on dialect will be presented for analysis. Establishing Northern Illinois vs. Southern Illinois To establish the difference between northern and southern Illinois, we first asked participants how they would differentiate between the two. Five of the seven interviewees answered that Interstate 80 is the dividing line; anything north of the interstate is considered northern Illinois and anything south of the interstate is considered southern Illinois. This is represented by the map below with Interstate 80 highlighted in red. Of the five interviewees that answered this way, four are from the suburbs of Chicago; because they are north of Interstate 80, these interviewees represent northern Illinois. Countering what the northern Illinois interviewees believe, the map below shows the Southern District of Illinois. Taken from the United States Attorney’s Office, the section in green highlights what the remaining two interviewees, as well as the government, believe to be southern Illinois. 2 Looking at the difference apparent between the two maps, it becomes clear that there are two differing perspectives on the dividing line between southern and northern Illinois; this supports the idea that perceptions of northern and southern Illinois are skewed depending on what part of the state one is from. Already, a difference in the way that people from the two respective areas think is established. What’s Your First Instinct? The Northern Perspective. While most people may be less than thrilled to admit it, the way a person speaks and sounds typically has an effect on an initial meeting between two people. Without knowing anything about a person, presumptions may take place. One of our hypotheses centered on discrimination that originates from northern Illinois against those from southern Illinois. In order 3 to expand on this idea, each interviewee was asked the following question: “Do you remember a time you assumed something specific about a person because of their northern/southern accent?” One of the first people interviewed was Emma, a senior Marketing major in the College of Business. Emma was born and raised in La Grange, Illinois, a southwestern suburb of Chicago. When she came to the University of Illinois, Emma subconsciously surrounded herself with people from northern Illinois, stating that “Of my core group of friends, I only have one friend from central Illinois.” Emma also believes that she does not have an accent; “Um, I’m going to go with no. Once in a while I’ll catch myself saying things with a slight Chicago accent, but it’s not as strong as most Chicagoans.” Emma was then asked the question above. Her response initially focused on the way southern Illinois people sound when pronouncing words and articulating ideas; “Definitely a red flag for me in that I’ll have to pay more attention to what they’re saying (…) I listen harder because of how they’re saying it.” She continues, assuming specific elements in regards to their lifestyle; “I think ‘Oh, a southern Illinois accent.’ Farmers. Rural. Small town lifestyle.” Emma recognizes the difference in dialect immediately, suggesting that people can, and do, distinguish between the different dialects. Frank, our second interviewee, is a senior History major in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences with a minor in Secondary Education. Frank was born and raised in Tinley Park, Illinois, a southwestern suburb of Chicago. Frank is also surrounded by friends from northern Illinois; “All of my close friends are from northern Illinois, or close to my hometown.” Frank does not believe that he possesses an accent. When asked, he responded with, “Uh, no. Well, slightly.” 4 When asked about his initial reaction to a southern Illinois accent, his response focused on lifestyle as well; “Small town. Farmer. I feel like they’re all small town farmers. They speak slower too.” Like Emma, Frank assumes a specific way of life based on a difference in dialect. Both interviews exhibit hints of stereotyping when they hear a southern accent; the interviewees assumed that that person must come from a small, agricultural town if they possess a southern Illinois accent. Frank also felt it necessary to note their speed of speech, highlighting the fact that it is slower than what he is used to. Although terming this as discrimination may be a bit harsh because it often implies very negative connotations, Emma and Frank both assume a specific way of life when a southern accent is heard; this supports our hypothesis in that both participants from northern Illinois perpetuate stereotypes. Expanding on this idea is Brittany Marrinson. In her work titled “Dialects around Illinois State University,” Brittany approaches the stereotypes surrounding the southern Illinois dialect as well; “A myth is that people from the south are slow and “hicks” because of their southern drawls and their dialect, or the different words and phrases that Midwesterners are used to.” Brittany expands on Frank’s stereotypes in that many people associate the southern Illinois drawl with a slower pace of speech; this drawl is often comprised of different terms that northern Illinois people are not used to. With these initial interviews, as well as Brittany’s article, our hypothesis was supported. What’s Your First Instinct? The Middle Perspective. After the people from northern Illinois were interviewed, Beth, a unique case when looking at northern and southern Illinois, was interviewed. Beth has moved six times in her life. Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Beth has lived in Dallas, Texas, Naperville, Illinois, and Overland Park, Kansas. Eventually, Beth’s family settled in St. Charles, Illinois, a suburb that lies to the 5 west of Chicago. In May, her family will move again to Atlanta, Georgia. While she may not directly reflect southern Illinois, she often displays a deeper accent than those from this respective area. For now, Beth identifies with northern Illinois. When asked about the people she is often surrounded by, Beth focuses on those from the north, but recognizes a few from southern Illinois; “I have friends in my classes, friends that I hang out with, friends from work, friends from Allan Hall – they’re all from the north. But Justin, Andy, Ben, Chris, ehhhh, I think that’s all. So a few from southern Illinois that I met while attending U of I.” Unlike Emma and Frank, Beth associates with a few different people from southern Illinois. Asked her views on whether or not she possesses an accent, Beth noted her participation in both; “(smiling) Yes, but mine changes. I can say Chicago with the heavy ‘a’, but I can also say fixin’ to and mean it, which is interesting.” Asked about her perceptions of northern and southern Illinois accents, Beth responded with similar ideas, but made sure to emphasize the positive connotations; “Hmm, southern Illinois. Small town. Family-oriented people that probably still attend church. So religious as well. I also think farming, but not in a negative way. They know the land. They know everyone in the town. But, like the north as well, this all depends on family and where you’re from.” Beth assumes small town as well, but immediately associates this with optimistic, strong qualities. When discussing farming, she associated it with a deep knowledge of the land, not a slower lifestyle. Because Beth blurs the distinction between northern and southern Illinois with her constant moving from the south to the north, she was also asked what she thinks when she hears a northern Illinois accent; “(They) probably went to a big high school. Both parents probably worked. They’re less community oriented.” When Beth hears a northern Illinois accent, she assumes a working, disconnected community. Like Emma and Frank, Beth makes negative 6 assumptions based on dialect; people from the north have money and do not take part in their larger community. This adds to our hypothesis, suggesting that both northern and southern Illinois people enable stereotypes. What’s Your Instinct? The Southern Perspective. The small town lifestyle that Emma and Frank often associate with southern Illinois is the lifestyle Amy, a senior Animal Science major in the College of Agriculture, Consumer and Environmental Sciences has lived for the majority of her life. Amy was born in Germany while her father served in the United States Airforce. When she turned five years old, her family moved to Beckemeyer, Illinois where she has resided ever since. Beckemeyer is located in Clinton County, a rural, southern Illinois community which prides itself on offering “the quiet of rural living.” Different than we assumed, Amy noted that she has more friends from northern Illinois because she “met a lot of people in college.” Asked about the perception of her own dialect, Amy also noted the absence of an accent. However, she does know that she “says some words differently.” Amy was then asked about her perception of the northern Illinois dialect; “I don’t really associate anything with the northern accent. I do notice a difference on how certain words are pronounced, like ‘bag’ for instance. That’s a big one. But I just associate the dialect with being from Chicago.” Unlike Emma and Frank, Amy does not associate a specific way of life with the northern Illinois accent. She does not follow the common stereotypes, and just assumes that the person talking is from the Chicago-land area. She does not make judgments based on income, schooling, or social settings. Personally, Amy does not perpetuate discrimination. 7 Nathan, our next interviewee, is from southern Illinois. Nathan is a senior, majoring in Aerospace Engineering in the College of Engineering. Nathan is from Alton, Illinois which is located in Madison County, a southern country of Illinois. When asked about his friends from northern and southern Illinois, Nathan noted that he has “more northern Illinois than southern Illinois. But to put a number on it…that’s tough.” Like all other interviewees, Nathan does not notice an accent; “I don’t believe I have much of one.” Asked about his initial reaction to northern Illinois accents, Nathan responded similar to Amy; “I don’t really think of anything. Southern Illinois is what I’m used to, but being in Champaign for four years makes it feel like the northern Illinois dialect is more normal. At first I thought it was funny, but that has worn out.” Nathan’s response shows that being on a campus where the majority of students come from northern Illinois affects his view on dialect; coming to this campus has made Nathan’s idea of what is the “normal” way of speaking change. Even though Nathan is from southern Illinois, he perceives the northern Illinois accent as the norm. The sixth interviewee comes from Albers, Illinois. Albers is located in Clinton Country, a southern county just east of the border line between Missouri and Illinois. Nick, a sophomore majoring in Biomedical Engineering in the College of Engineering was born and raised in Albers. When asked about the makeup of his friends, Nick answered that he has “approximately 200 from up north, and 100 from down south.” Unusual based on the rest of our research, Nick believes that he does have an accent; “I noticed it when I first came to school because all of the Chicago kids pointed it out. I did say ‘Chemistry’ with a kind of twang. I didn’t think I had an accent until I was around people who spoke differently than me. And I do get teased a little bit by my friends. But this semester I noticed that I lost my twang and started to say ‘in’ differently.” Coming into contact with others from the north, Nick’s perspective on dialect 8 changed. Linking this with the idea of “double consciousness,” which is discussed in Vershawn Young’s article titled “Nah, We Straight’: An Argument against Code Switching,” Young addresses this changing perspective; double consciousness is defined as “having to always look at one’s self through the eyes of others” (52). In order to even consider the idea of differing dialects, or notice that he had one, Nick had to come to the University of Illinois and see himself through the eyes of other people; people from northern Illinois pointed out that he spoke differently than they did, and this is what allowed Nick to notice that a difference was present. The above findings that discuss possession of a dialect expand our interview question; each interviewee failed to recognize that they had an accent. While Nick eventually noticed one, it was not until after he was placed in a different context with others who spoke in another way. This suggests that dialects, and views concerning ownership, are relative to position. While many variations in language occur, it is difficult for people to realize that they speak with an accent because the dialect that they are used to, according to their perception, is normal. Like all other interviewees, Nick was asked about his initial reaction to the northern Illinois dialect; “I assume that people with a Northern accent are from Chicago. And are rich. A person comes off as nicer if they have a southern accent. Personally, I prefer my southern accent over the northern one.” Supporting our hypothesis further, Nick assumes a certain way of life based on the northern dialect; to him, the dialect suggests that people from this area have a lot of money. If they’re from the north, they’re rich. This idea is expanded in Morris Young’s “Re/Visions: Asian American Literacy Narratives as Rhetoric of Citizenship.” The idea of upward social mobility and success, as Nick links with the northern Illinois accent, is analyzed. Young discusses how the perception of social mobility, and the groups that are capable of moving up, affects various groups of people. Nick also assumes that people from northern 9 Illinois are ruder than those from southern Illinois. Like many other interviewees, Nick assumes a specific way of life based on dialect. As the interviews suggest, our research points to discrimination that is perpetuated from both northern and southern Illinois students; when people speak, assumptions are made. So, there is discrimination…What now? Social Experiences at UIUC. We have just seen that assumptions are made based on dialect; whether the participants came from northern or southern Illinois, different stereotypes were applied to different accents. While the aspect of discrimination was the main focus for our research project, we also wanted to see if the participants’ social or academic life on UIUC’s campus has been affected by dialect. Amy, the participant from Beckmeyer, Illinois, was asked to recall a time when her home dialect affected her experience. Immediately, Amy had a response; “I have had many social experiences where people are interested in me because of the way I speak. For example, guys will use pickup lines such as ‘I like a girl with a southern accent.’ This is frustrating because they don’t even know anything about me. They don’t even know my name. They don’t even ask.” Because of her southern Illinois accent, often associated with a girl that can be “taken home to mom” or a girl that is “laid back and down to earth,” boys are immediately attracted to her; they do not initially care about her name or her personal life; they are attracted to her purely because of the way she speaks. Amy is particularly annoyed by it because she does not believe she has an accent; “I’m not from the south. I’m not from Alabama. I’m not from Georgia. I’m from Illinois.” Without knowing her name, boys attempt to advance sexually on her. Like stated before, assumptions are constantly made as boys attempt to pick Amy up in different social settings, sometimes negatively affecting her social experience here at UIUC. While Amy’s story does provide great 10 insight into different social settings on campus, neither Nick nor Nathan have been negatively affected because of their southern Illinois dialect. Emma, Frank and Beth, the interviewees from La Grange, Tinley Park, and St. Charles respectively, were asked the same question - “Describe a time when your home dialect affected your academic or social experience at UIUC.” Unlike Amy, none of the participants from northern Illinois had a negative social experience: Emma: “Overall, dialect doesn’t affect my social experience. I’m not the odd man out. Ever.” Frank: “It doesn’t really. I speak like the majority of the people down here because most of the people are from the suburbs. I don’t choose my friends based on how they speak - Dialect shouldn’t be a determining factor. Friends come from where you’re from, which is why I’m friends with mostly people from the suburbs.” Beth: “My northern dialect doesn’t play an important role in my social or academic setting.” Based on speculations found in their responses, we hypothesize that one of the reasons northern people are not negatively affected in various social settings is because they are the majority on UIUC’s campus; it is difficult to be discriminated against, or take part in negative experiences, when the way a person speaks is dominant within group settings. From the perspective of participants, it seems that people with a southern Illinois dialect are more likely to be negatively affected. From the interviews above, we have speculated that the ideas surrounding dialect, and whether or not one personally possesses one, is relative to position; the area that a person is from is considered the “norm” and often, people do not think that they possess a dialect. The interviews also suggest that discrimination does exist from both northern and southern Illinois people; assumptions based on lifestyle and income are made. Social experiences can also be affected by the way a person speaks. While these interviews have greatly enriched our findings, 11 this study is not completely inclusive and does not represent every northern and southern Illinois student’s beliefs. After taking the time to learn more about the difference between the two dialects, some other interesting questions were raised: Does location play a role in deciding one’s major? Many assume that those from southern Illinois major in Agriculture – does this assumption hold true? Answering these questions, and more like them, is the next step in our research. 12 Works Cited Cramer, Jennifer. “The effect of borders on the linguistic production and perception of regional identity in Louisville, Kentucky.” 2010. Curtshone, Glasper. “Cracking the Code: A Look at a Misinterpreted Dialect.” 2010. Belay, Robel. “Code Switching: A Social Adaptation.” 2009. Marrinson, Brittany. “Dialects Around Illinois State University.” 2005. Mbanza, Alana. “The Myth of the Black Townie.” 2008. Williams, Joseph M. "The Phenomenology of Error." College Composition and Communication: 152- 68. Young, Morris. Minor Re/Visions: Asian American Literacy Narratives as a Rhetoric of Citizenship. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. 2004. Young, Vershawn A. “’Nah, We Straight’: An Argument Against Code Switching.” 49-76. 13