The Impacts of Tariff Reductions on Real Imports in Malaysia from

advertisement

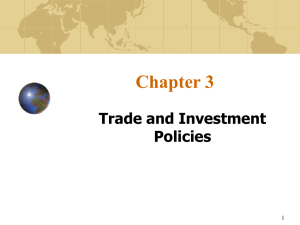

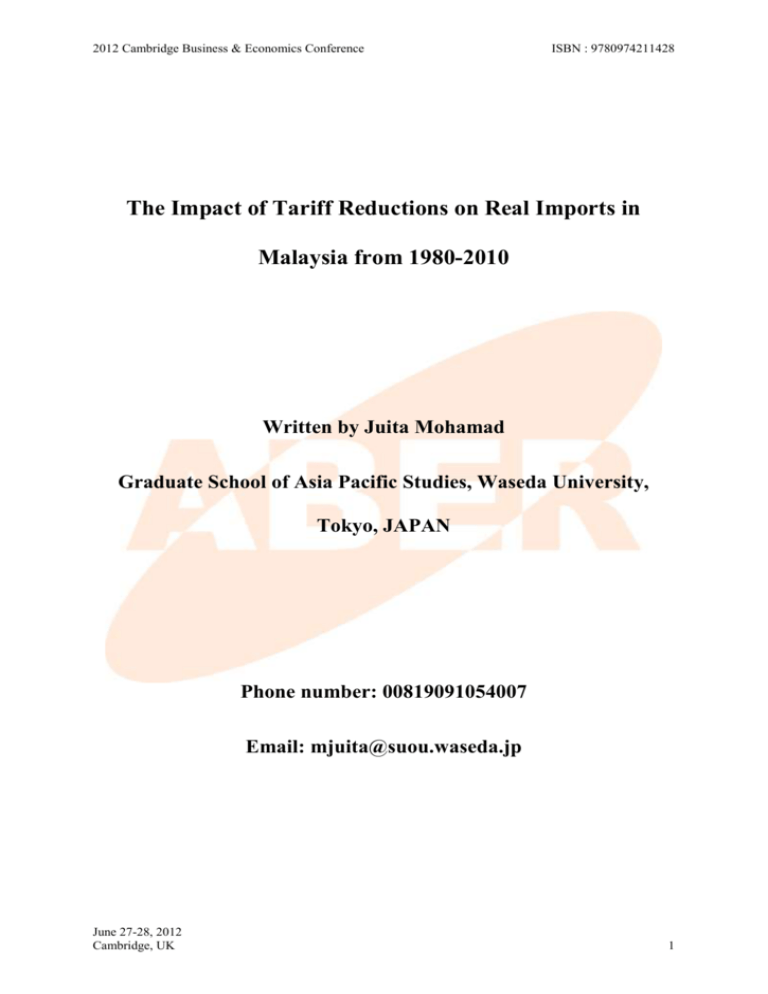

2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 The Impact of Tariff Reductions on Real Imports in Malaysia from 1980-2010 Written by Juita Mohamad Graduate School of Asia Pacific Studies, Waseda University, Tokyo, JAPAN Phone number: 00819091054007 Email: mjuita@suou.waseda.jp June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 1 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 The Impact of Tariff Reductions on Real Imports in Malaysia from 1980-2010 Abstract This paper investigates the long run relationship of drastic tariff reductions on the real imports from 1980 - 2010 in Malaysia using the Johansen cointegration analysis. Time series data for eight sectors according to the Standard International Trade Classification were compiled. A dynamic error correction model is used to overcome the limited number of observations for each of the sectors. A log-linear regression is run for each sector to test the effects of income, domestic price, import price, tariff rates on real imports in each of these sectors. With the independent variables selected, it is expected that as imports increase, income and domestic price increase, while import price and tariff rates decrease. The results from the regression exercise are mixed. It is observed that those sectors conforming to the hypothesis are sectors concerning with basic necessities of the Malaysian consumers and producers. The import demand for sectors with basic necessity goods are more sensitive with the changes in tariff rates compared to sectors with non-basic necessity goods. For the latter group, even when tariff rates are increasing, import demand still increases as these products are mostly intermediary goods needed for production and processing activities. This interpretation is appropriate for the case of Malaysia, whereby manufacturing activity is the main driver of its domestic economy since the early 1990s. This study is beneficial to determine the behaviour pattern of each sector in the wake of reduced import prices and drastic tariff cuts. Key words: tariff reductions, real imports, Stolper-Samuelson theorem, domestic price, import price, Malaysia June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 2 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 Introduction As the world economy shifts into a more globalized era, presently every developing nation is harnessing their resources in aneffort to take part in a more free trade regime.Globalization promotes the practice of free trade and it is believed to promote a more levelled playing field in the world market, as tariff rates are driven down to near 0%. In other words, protectionism policy is at the brink of extinction with the rise of globalization. Globalisation in the long run, rewards efficient producers the competitive advantage that ensures its position in the global market.Even with the promise of more wealth and ensuring increased welfare for all, the issue of increased competition domestically in the midst oftrade liberalization for both developed and developing nations, are widely discussed. In his book Making Globalization Work(2006), Stiglitz emphasized that with globalization, "Everyone was supposed to be a winner - those in both developed and thedeveloping world. Globalization was to bring unprecedented prosperity to all." Even Adam Smith, 1776 promoted the idea of free tradei. Here was how he put it at that time: It is the maxim of every prudent master of a family, never to attempt to make at home what it will cost him more to make than to buy.. . . If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it of them with some part of the produce of our own industry, employed in a way in which we have some advantage. With all of the advantages of free trade, some economists are sceptical about the downside of globalisation which includes increased competition in the domestic economy which can lead to the absolution or demise of local businesses. With the world as one big market, local producers are forced to compete with cheaper imported goods or higher quality products. The survival of the fittest is being tested in today’s economic environment, with more pressure being put not only onto business, but nations as well. June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 3 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 Malaysia, a small open economy, in the South East Asian region, is taking this threat and turning it into an opportunity. The ASEAN bloc has become the hub for intratrade activity. Intra- regional trade has been growing. According to Otsuki, 2011, intra-regional trade for manufactured goods within the ASEAN region has increased to 150 billion USD in 2008 if compared to 70 billion USD in year 2000ii. What makes this region a part of the world engine of economic growth nowadays, is that as we increasingly trade intermediary goods among ourselves in the assembly process of commodities, we also import and re-export the goods, outside the region to China, the US and Europe as end users for our products. This activity is how we are known as the entreportcenter. Due to the importance of this intra trade activity as the driver of the nation’s economy, it is important to examine the effects of the reduction of tariff rates on real imports. It is also important to see how changes in income, domestic pricing, import pricing effect real imports. The study will take a look at the behaviour of these variables in different sectors according to the segregation of Standard Industrial Trade Classification, Revision 3 at one digit level iii.The paper examines how reduction in import duties affect the demand for real imports in selected sectors in a small, open, developing economy of Malaysia using time series data from 1980 to 2010. Background on Tariff Reduction through AFTA and WTO Initiatives On the 8th of August 1967, a simple yet clear agreement was drawn up between the six Founding Fathers of the six main Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) members, which were Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. According to the document, ASEAN is seen as representing ―the collective will of the June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 4 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 nations of Southeast Asia to bind themselves together in friendship and cooperation and, through joint efforts and sacrifices, secure for their peoples and for posterity the blessings of peace, freedom and prosperity. It is with that basic drive of cooperation and joint efforts, ASEAN Free Trade Area (AFTA) came about in year 1992. When the AFTA agreement was signed, the primary goals were to ―increase ASEAN's competitive edge as a production base in the world market through the elimination, within ASEAN, and to attract more foreign direct investment to ASEAN. Looking back since its inception, AFTA has come a long way in changing trade patterns in Malaysia and the South East Asian region. As from year 2002, it is now in full swing, ― aiming to promote the region‘s competitive advantage as a single production unit. Even though specific rules and priorities are given for the elimination of tariff mainly for manufacturing and agriculture products in member countries, the non-tariff barrier is also expected to promote greater economic efficiency, productivity, and competitiveness. To observe how far the region has come in promoting a leveled playing field for its member countries, as of 1 January 2005, ― tariffs on almost 99 percent of the products in the Inclusion List of the ASEAN-6 have been reduced to no more than 5 percent. More than 60 percent of these products have zero tariffs. The average tariff for ASEAN-6 has been brought down from more than 12 percent when AFTA started to 2 percent today. The implementation of the Common Effective Preferential Tariff –AFTA Scheme (CEPT-AFTA) was even accelerated further in January 2004, when Malaysia decided to reduce tariffs for Completely Built Up (CBUs) and Completely Knocked Down (CKDs) automotive units to smoothly meet its CEPT commitment one year earlier than schedule. This proved to be a big commitment on behalf of Malaysia, as Proton, its national car industry have been shielded under heavy protectionist policy since year 1985. When full trade liberalization is achieved, the area could not only be beneficial for the 10 member countries but also holds attractiveness for trading partners all around the worldiv. June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 5 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 Malaysia is a founding Member of the WTO by virtue of its membership in the GATT since 1957. Through active participations in WTO negotiations, Malaysia continues to ensure that trade regulations and trade measures that are negotiated are fair and provide the flexibility for Malaysia to continue its development policyv. To date, under the commitment of GATT/WTO, the average MFN applied tariff rates for Malaysian goods are down to 8.8% in year 2010 compared to 11.3% in year 1995vi. This shows the continuous effort and commitment of Malaysia as a WTO member and how tariff rate reductions are not only induced by the ASEAN bloc agreement regionally but also the commitments of the GATT/WTO at an international level. Literature Review There are many empirical studies on demand of imports. For example in the case of Malaysia, the studies which are conducted to examine the behaviour of import demand are Mohammad (1980), Semudram (1982), Awang (1988), and the Malaysian Institute of Economic Research (MIER) Annual Model (1990). These studies estimated a traditional import demand function, where the dependant variable is the volume of imports, where the independent variables are real income and relative prices. For these studies, the assumption is that data are stationary. These studies were done when cointegration analysis and error correction model were not standard practice for time series analysis. Hence they used OLS regression models or partial adjustment approaches to estimate the import demand function. Granger and Newbold (1974) emphasized that if the stationary assumption is not satisfied, this can lead to spurious regression. Due to this, the OLS results would be unreliable. From previous literature review, the traditional import demand function has branched out, to include other independent variables which can affect real import such as tariff rates. Caesar June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 6 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 (2011) have used tariff and exchange rate as an extension of the general import demand function to study the determinants of import demand in Zambia. Egwaikhide (1999) have incorporated tariff rates into its import prices, in the empirical study for Nigeria. Karacaovali (2011) has also incorporated tariff rates in its model. The choice between a linear and log-linear import demand equation is important because the influence of explanatory variables on demand is affected by the functional form. Kmenta (1971) stated that misspecification of the functional form can result in misspecification of the error term and violation of the classical assumptions of the error term. This leads the estimates to be biased. Previous studies by Khan and Ross (1977), Boylanet. al (1980) and Doroodian et. al (1994) has proven that specification of a log-linear form is preferable when estimating import demand functions. Data The variables used for this study areReal Imports, Gross National Income, Domestic Price Index, Import Price Index and Simple Average Tariff Rates. All of the annual data from year 1980-2010 were supplied by the Department of Statistics Malaysia except for the tariff rates, which were obtained from the WITS website. The real imports variable is based on import value and not quantity as it is more comparable among the goods in a certain sector. The sectors are divided into 9 Standard of Industrial Trade Classification at 1- digit level. The author constructed an index for the real imports for each sector.For a more accurate analysis, the author chose the log form, so that the result of the coefficients of the variables can be interpreted as degree of elasticity. Due to lack of data, the author has focused her analysis on June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 7 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 only 8 sectors instead of 9 sectors according to the SITC Revision 3 segregation. These sectors are: 0. Food and Live Animals, 1. Beverages and Tobacco, 2. Crude Materials Inedible Except Fuels, 3. Mineral fuels, Lubricants and Related Materials, 4. Animal and Vegetable Oils, Fats and Waxes, 5. Chemicals and Related Products, 6. Manufactured Goods Classified Chiefly by Material, Machinery and Transport Equipment, 8. Miscellaneous Manufactured Articles. The author did not include the last sector, 9. Commodities and Transactions Not Classified Elsewhere in the SITC in this study due to data unavailability. Methodology and Findings This methodology is replicated from the study by Tang T.C. and Mohammad H. A. (2000), which looked at the demand of aggregate import as a whole for Malaysia. Instead of looking into aggregate imports, the author uses the same analytical steps in observing the different behavior of demand of imports for 8 different sectors. The traditional formula for an import demand function can be specified that relates the quantity of imports demanded to income, the price of imports and the price of the domestic substitute. Import demand at time t is written as below: Mit = ƒ (Ydt, Pmit, Pdit) (1) where Mit is the quantity of imports demanded for commodity class i (to the ithat one digit level of the Standard International Trade Classification) at period t, Ydt is domestic income, Pmit is the price level for the import commodity class i and , Pdit is the price level for the domestic good i at time t. The theory of demand suggests that ordinary demand functions are homogenous of degree zero in prices and income. This implies that the absence of money illusion and allows the June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 8 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 demand for imports to be expressed as a function of real income and relative prices (Siddique, 1997). Therefore the traditional import demand function can be rewritten as: Mit = g (Yt, Rit) (2) Where Ytequals toYdt/Pdtand represents real domestic income and Ritequals to Pmit/Pdit, which is the price of the ith digit import relative to the domestic price. This equation has the assumption that the effect of 2 price variables on demand will be equal but in opposite directions. Gafar, 1988 explained that the two most common functional forms used in the literature are in the linear and log-linear formulations. In linear terms, the empirical import demand function can be written as: Mit = δ + α0Yt+β0Rit +εit (3) Where δ is the constant term, α0 is the marginal propensity to import,β0 is the import coefficient of relative prices andεit, is the random error term. From economic theory point of view, it is expected that α0>0. However Goldstein and Khan, 1976 explained that if imports represent the difference between domestic consumption and domestic production of imported goods, production may rise faster (slower) than consumption in response to rise in real income. Due to this, imports could fall (rise) as real income increases, resulting in negative (positive) sign for the coefficient α0. The author however has constructed an adjusted import demand function, to include the tariff rate variable, T as an extension from the traditional function. Additionally in this new equation, the import price level and domestic price level are disaggregated to relieve the restrictions imposed on the traditional demand function.The author has chosen to disaggregate the log import price and log domestic price, due to the assumption that these prices do not move in the same degree, and also in opposite directions. For this kind of study June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 9 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 both the linear and log linear specifications have been used as highlighted in the literature review section. The author has chosen the latter due to the fact that it is more commonly used. At the end of the day, the selection between these 2 forms of specifications is intuitional based on previous literatures. With thedisaggregation of the two prices, the behaviour of the import prices and domestic prices can be observed, for specific commodity groupings. As log-linear form is mostly adopted for this empirical study, the newly adjusted import demand function can be written as: lnMit = δ + φ0lnYt-β0lnIit +ѲlnDit- σlnTit +εit (4) whereln is the natural logarithm, Iitis the import price level of the ith commodity group, Dit is the domestic price level of the ith commodity group andTit, is the tariff rate for the ith commodity group according to the SITC segregation. Εit is the random error term. For this study, Error Correction Model (ECM) is being used due to limited annual observations for each sectors from year 1980-2010 (only 31 observations). ECM is the most appropriate for limited observations in time series. OLS is not appropriate for this time series study, as the outcome will be highly unreliable as mentioned in the literature review section. Before the ECM analysis could take place, the author tested the time series data for each sector for multicollinearity problems. For each sector, Augmented Dickey Fuller (ADF) testing was undergone. The regression equation for ADF test (Dickey&Fuller, 1979) is stated as follows: ∆𝑌𝑡 = 𝑎 + 𝑏𝑡 + 𝑐𝑌𝑡 − 1 + ∑𝑘𝑖=1 𝑑∆𝑌𝑡 − 1 + 𝑒𝑡 (5) where∆ is the first difference operator, t refers to time trend, and k is additional terms in the first differences for the Augmented Dickey-Fuller test, et is the regression error assumed to June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 10 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 be stationary with zero mean and constant variance. The test were carried out to test the null hypothesis of a unit root (c=0). The results are presented in Table 1 below. The table highlighted that all variables real imports, GNI, Domestic Price, Import Price and Simple Average Tariff are integrated in order one, I(1). This means that they are stationary in their first difference. Insert Table 1a, 1b and 1c here After the ADF test were undergone, the author went on to the vector error correction model. Before the modelling could be done, for the Johansen method, it is crucial to specify an appropriate lag length for the VAR. For all of the eight subsectors, 2-year lag length was the most appropriate. As for the trace test, for each different sectors the cointegration ranking differs. Table 2 below, shows the Johansen test for cointegration and the appropriate lags chosen for each of the eight sub sectors. Table 3 presents the normalised cointegrating equation estimate for all of the subsectors. Insert Table 2a-h, here Insert Table 3a-h, here In the next step, error correction model was estimated. The rank is set to 1, which is the default number of the error correction terms. An error correction model was estimated to examine the long run behaviour of Malaysian imports (according to their 8sectors). The lagged residual from the Johansen Cointegration Equation was included the dynamic general ECM. The general equation for ECM with 2 lag length is stated as below: ∆ln Mt = b0 + b1i∆ lnM t-2 + ∑𝑛𝑖=0 𝑏2𝑖 ∆ ln Yt-2+ ∑𝑛𝑖=0 𝑏3𝑖 ∆ lnIt-2 + ∑𝑛𝑖=0 𝑏4𝑖 ∆ lnDt-2 𝑛 +∑𝑖=0 𝑏5𝑖 ∆ lnTt-2 + b6 ECt-2 + error term June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK (6) 11 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 where EC is residual error derived from the cointegrating vector. This dynamic general equation is used separately for all the 8 sectors and presented in the next section. Analysis of Findings The coefficients of income, domestic prices, import prices and simple average tariff rates shows both expected and unexpected signs and are both significant and not significant, depending on the sector being analysed. In this section a detailed breakdown of the findings will be presented. Let us look at the normalised cointegrating coefficients results for each of the 8 sectors in Table 3 below. Insert Table 3 here – result for vec for all sectors- make table Let us take a look at the results of the coefficients, sector by sector. A very interesting finding from this analysis is that the coefficient for GNI as a proxy of income, α0 is negative in relations to import demand. From economic theory point of view, it is expected that α0>0. However Goldstein and Khan, 1976 explained that if imports represent the difference between domestic consumption and domestic production of imported goods, production may rise faster (slower) than consumption in response to rise in real income. Due to this, imports could fall (rise) as real income increases, resulting in negative (positive) sign for the coefficient α0. For Sector 0, Food and Live Animals, all the signs exhibited the expected signs. In this case, even when income decreases by 1 point, real imports will still increase by 0.61 point. In this June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 12 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 sector, tariff rates do affect real imports. When average tariff decreases by1 point, real imports will increase by 0.17 point. The second sector which exhibits the expected signs for its variables is Sector 6. Manufactured Goods Classified Chiefly by Material. For this sector, in the long run, domestic and import prices play important roles in affecting real imports. The long run elasticities of import demand with respect to import price and domestic price are -27 and 30. It is not surprising then that the tariff coefficient sign is positive. For this sector in the long run, even when tariff increases by 1 point, real imports will still increase by 1.18 points. It is clear that for manufactured goods, tariff rates do not affect the import demands for this sector. A 1 point increase in import price, will decrease real imports by 27 points, while a 1 point decrease in domestic price, will decrease imports by 31 point. With our re-exporting activity, the more we export the goods, the more imports are needed as intermediary goods to support this activity.This is not surprising as Malaysia’s imports and exports of manufactures from overall merchandise trading account for 70% as of year 2010. This is further highlighted by Graph 1 in the Appendix. The last sector with expected signs for its variables is Sector 8, Miscellaneous Manufactured Articles. In this sector, footwear, furniture and articles of apparel and clothing accessories which are basic necessity goods are included. The implied long run elasticties of import demand with respect to import price and average tariff are -1.97 and -1.60. Here tariff rate does play a role in affecting real imports. For all the other sectors, the variable signs are not as expected. However, due to the fact that this paper focuses on the effect of trade reform on imports, it is important to see how changes in tariff rates do or do not, influence the changes in import demands for different goods in June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 13 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 different sectors. Table 4 below present the results for the signs and significance of the tariff rate variable. Insert Table 4 here – tariff rate As can be observed in the Table above, only 3 sectors are presented to have negative signs for their tariff variable in relations to real import. These sectors are Food and Live Animals, Animal and Vegetable Oils, Fat and Waxes and Miscellaneous Manufactured Articles. Their coefficients are -0.17, -3.38 and -1.60 respectively with all being highly significant at 1% level. What all of them have in common is that, these are basic necessity goods. The rest of the sectors have positive signs for their tariff variables in relations to real import. These sectors are 1. Beverages and Tobacco, 2.Crude Materials Inedible Except Fuels, 3.Mineral fuels, Lubricants and Related Materials, 5.Chemicals and Related Products, 6. Manufactured Goods Classified Chiefly by Material and 7. Machinery and Transport Equipment. Their coefficients are 0.11, 0.67, 1.30, 0.49, 1.18 and 0.11 respectively, with all being highly significant at 1% and 5% level except for Sector 7. For this sector, tariff rate is insignificant in affecting import demand. These are all non- basic necessity goods except for beverages and tobacco sector. Beverages and tobacco sector belongs to a special group. Higher taxes have always been imposed on tobacco and alcoholic beverages in Malaysia, making it more expensive and therefore, unavailable for youths and children. Due to this even when tariff rates are higher, due to preferences or lack of choice, these goods are still high in demand for Malaysian consumers. Examining the results of the analysis, it can be concluded that the import demand for sectors with basic necessity goods are more sensitive by the changes in tariff rates compared to sectors with non-basic necessity goods. For the latter group, even when tariff rates are increasing, import demand still increases as these products are mostly intermediary goods June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 14 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 needed for production and processing activities. This interpretation is appropriate for the case of Malaysia, whereby manufacturing activity is the main driver of its domestic economy. Conclusion A number of conclusions can be drawn from this study. Firstly, if researchers are to obtain robust results it is important they choose the right methodology, appropriate for its time series data limitation. As this data set, has only 31 observations for each of its 8 sectors, the author has chosen the dynamic error correction model to estimate the long run behaviour of Malaysian imports according to sectors from year 1980-2010. Secondly, the negative sign presented for the income coefficient suggests that in Malaysia, according toGoldstein and Khan, 1976 imports represent the difference between domestic consumption and domestic production of imported goods, production may rise faster (slower) than consumption in response to rise in real income. Due to this, imports could fall (rise) as real income increases, resulting in negative (positive) sign for the coefficient α0. Thirdly, the empirical results suggest that only 3 sectors which include basic necessity goods for end users and producers, have all the expected signs for their variables. These sectors are Food and Live Animals, Manufactured Goods Classified Chiefly by Material and Miscellaneous Manufactured Articles. Fourthly, as this paper focuses on the effect of trade reform on imports, it is important to see how changes in tariff rates do or do not, influence the changes in import demands for different goods in different sectors. The import demand for sectors with basic necessity goods are more sensitive by the changes in tariff rates compared to sectors with non-basic necessity goods. For the latter group, even when tariff rates are increasing, import demand still June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 15 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 increases as these products are mostly intermediary goods needed for production and processing activities. This interpretation is appropriate for the case of Malaysia, whereby manufacturing activity is the main driver of its domestic economy since the early 1990s. i Taken from the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/FreeTrade.html Statistics were taken from the paper by Otsuki, 2011 at http://www.osipp.osakau.ac.jp/archives/DP/2011/DP2011E006.pdf iii For a more information please visit http://unstats.un.org/unsd/cr/registry/regcst.asp?cl=14 iv Information obtained from the ASEAN Secretariat website v Taken from the MITI website, http://www.miti.gov.my/cms/content.jsp?id=com.tms.cms.section.Section_f5694606-c0a81573-78d578d5759be8c9 vi Tariff rates obtained by the World Trade Indicators Report 2010 athttp://info.worldbank.org/etools/wti/docs/Malaysia_taag.pdf ii June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 16 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 References Awang, A. H. (1988) An evaluation of the structural adjustment policies in Malaysia. In Proceedings of the Eighth Pacific Basin Central Bank Conference on Economic Modelling, Bank Negara Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, November 11-15 Boylan et al. (1980) The functional form of aggregate import demand equation: a comparison of three European economies, Journal of International Economics 10, 561-566 Cheelo, C. (2011) Determinants of Import Demands Zambia, University of Zambia, Published on the Internet by the SAP - Project at http://www.fiuc.org/iaup/sap/ Doroodian et al. (1994) An examination of the traditional aggregate import demand function for Saudi Arabia, Applied Economics 26, 909-915 Dickey, D. A., & Fuller, W.A (1979) Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root, Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74, 427-431 Egwaikhide, F. (1999) Determinants of Imports in Nigeria: A Dynamic Specification, AERC Research Paper 91, African Economic Research Consortium, Nairobi Gafar, J.S. (1988) The determinants of import demand in Trinidad and Tobago: 1967-1984, Applied Economics, 20, 303-13 Goldstein, M. and Khan, M.S (1976) Large versus small price changes and the demand for imports, Journal of International Economics 7, 149-160 Granger, C. W. J. and Newbold, P. (1974) Spurious regressions in econometrics, Journal of Econometrics, 2, 111-20 J. Kmenta, Elements of Econometrics, Macmillan, New York (1971) Karacaovali, B. (2011) Trade policy and Trade Reform in a Developing Country Khan, M.S. and Ross, K.Z, The functional form of the aggregate import demand equation, Journal ofInternational Economy 7, 200-225. Malaysian Institute of Economic Research (1990) MIER Annual Model, In Imaoka, H., Semudram, M., Meyanathan. S. and Kevin Chew (eds). Models of the Malaysian Economy: A survey. Kuala Lumpur, MIER Mohammad H. A. (1980), A demand equation for West Malaysian Imports, Journal Ekonomi Malaysia, 1, 109-20. Otsuki (2011) Quantifying the benefits of Trade Facilitation in ASEAN, OSIPP Discussion Paper : DP-2011-E-006 June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 17 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 Semudram, M. (1982), A macro-model of the Malaysian economy, 1957-1977, The Developing Economies, June Siddique, M.A.B (1997), Demand for Machinery and Manufactured Goods in Malaysia, Mathematics and Computers in Simulation43, 481-486 Tang T.C. and Mohammad H. A. (2000) An aggregate import demand function for Malaysia: a cointegrating and error correction analysis, Utara Management Review, 1, 43-57 June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 18 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 Appendix Table 1a Sector/Variable 0 ADF level 1 FD ADF level 2 FD ADF level 3 FD ADF level * -3.15 * -2.48 ** -2.17 3.84 3.84 0.41 lngni -0.81 ** -0.81 ** -0.81 ** -0.81 3.43 3.43 3.43 lndomprice -2.14 ** -2.23 * -1.56 *** -1.43 3.41 3.41 4.17 lnimpprice -4.33 *** -2.44 -2.22 *** -1.91 4.65 4.65 4.49 lnsimpleavtariff -2.26 *** -2.58 *** -2.50 ** -1.72 4.30 4.30 3.70 *,**,*** denoted rejection of a unit root hypothesis based on MacKinnon’s critical value at 1 percent, 5 percent and 10 percent. Note: 1) Constant and trend were included in level, and only constant in first difference (refer to Baghestani& Mott, 1997). In common practice, an augmentation of one or two, generally appears to be sufficient to secure lack of autocorrelation of the error terms (Ghatak, Milner &Utkulu, 1997) One augmented lag was used due to limitation of annual data (refer to Doroodian, Koshal& Al- Muhanna, 1994:912) ln imports -2.83 FD 2.75 3.43 3.25 2.67 3.20 * ** *** *** ** Table 1b Sector/Variable 4 ADF level ln imports -4.174 5 FD -7.13 *** -4.174 FD -7.13 ADF level *** -1.456 7 FD 2.926 3.425 3.566 3.458 3.602 ADF level * FD -0.665 ** -0.805 ** -0.802 3.425 lndomprice -2.428 *** -2.428 ** -2.587 ** -4.052 3.361 lnimpprice -3.952 *** -3.952 *** -3.007 ** -1.887 4.258 lnsimpleavtariff -2.247 -3.97 *** -2.247 ** -1.672 ** -2.35 3.396 *,**,*** denoted rejection of a unit root hypothesis based on MacKinnon’s critical value at 1 percent, 5 percent and 10 percent. Note: 1) Constant and trend were included in level, and only constant in first difference (refer to Baghestani& Mott, 1997). In common practice, an augmentation of one or two, generally appears to be sufficient to secure lack of autocorrelation of the error terms (Ghatak, Milner &Utkulu, 1997) One augmented lag was used due to limitation of annual data (refer to Doroodian, Koshal& Al- Muhanna, 1994:912) lngni June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK -0.805 3.425 7.214 3.828 ADF level 6 ** -0.805 19 2.459 ** 3.596 *** 5.649 *** 4.447 ** 3.375 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 Table 1c Sector/Variable 8 ADF level ln imports -0.154 lngni -0.802 lndomprice -0.925 lnimpprice -3.88 -2.336 lnsimpleavtariff FD * 2.823 ** 3.596 ** 3.545 ** 3.649 *** 3.968 *,**,*** denoted rejection of a unit root hypothesis based on MacKinnon’s critical value at 1 percent, 5 percent and 10 percent. Note: 1) Constant and trend were included in level, and only constant in first difference (refer to Baghestani& Mott, 1997). In common practice, an augmentation of one or two, generally appears to be sufficient to secure lack of autocorrelation of the error terms (Ghatak, Milner &Utkulu, 1997) One augmented lag was used due to limitation of annual data (refer to Doroodian, Koshal& Al- Muhanna, 1994:912) Results for Trace Test for Cointegrating Vector Table 2a Sector 0 Johansen tests for cointegration Trend: constant Sample: 1982 - 2010 maximum rank 0 1 2 3 4 5 parms 30 39 46 51 54 55 June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK LL 356.99761 395.24529 408.28555 416.56421 423.32156 424.33671 Number of obs = Lags = eigenvalue . 0.92848 0.59316 0.43501 0.37251 0.06762 29 2 5% trace critical statistic value 134.6782 68.52 58.1829 47.21 32.1023 29.68 15.5450 15.41 2.0303* 3.76 20 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 Table 2b Sector 1 Johansen tests for cointegration Trend: constant Sample: 1982 - 2010 maximum rank 0 1 2 3 4 5 parms 30 39 46 51 54 55 Number of obs = Lags = LL 281.49667 310.20511 321.79697 329.80182 333.67385 335.07264 eigenvalue . 0.86192 0.55042 0.42424 0.23435 0.09196 29 2 5% trace critical statistic value 107.1519 68.52 49.7351 47.21 26.5513* 29.68 10.5416 15.41 2.7976 3.76 Table 2c Sector 2 Johansen tests for cointegration Trend: constant Sample: 1982 - 2010 maximum rank 0 1 2 3 4 5 parms 30 39 46 51 54 55 Number of obs = Lags = LL 307.75654 329.31429 339.38405 344.35754 347.24741 348.17139 eigenvalue . 0.77389 0.50066 0.29036 0.18070 0.06173 29 2 5% trace critical statistic value 80.8297 68.52 37.7142* 47.21 17.5747 29.68 7.6277 15.41 1.8479 3.76 Table 2d Sector 3 Johansen tests for cointegration Trend: constant Sample: 1982 - 2010 maximum rank 0 1 2 3 4 5 parms 30 39 46 51 54 55 June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK LL 276.54163 295.00419 310.9101 320.86889 323.97805 325.4728 Number of obs = Lags = eigenvalue . 0.72009 0.66612 0.49682 0.19299 0.09795 29 2 5% trace critical statistic value 97.8623 68.52 60.9372 47.21 29.1254* 29.68 9.2078 15.41 2.9895 3.76 21 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 Table 2e Sector 4 Johansen tests for cointegration Trend: constant Sample: 1982 - 2010 maximum rank 0 1 2 3 4 5 parms 30 39 46 51 54 55 Number of obs = Lags = LL 247.68692 264.54345 278.44208 287.94386 291.8668 295.59271 29 2 5% trace critical statistic value 95.8116 68.52 62.0985 47.21 34.3013 29.68 15.2977* 15.41 7.4518 3.76 eigenvalue . 0.68730 0.61654 0.48071 0.23704 0.22660 Table 2f Sector 5 Johansen tests for cointegration Trend: constant Sample: 1982 - 2010 maximum rank 0 1 2 3 4 5 parms 30 39 46 51 54 55 Number of obs = Lags = LL 383.87484 402.83103 412.56721 418.09083 421.32271 421.5472 eigenvalue . 0.72946 0.48904 0.31678 0.19980 0.01536 29 2 5% trace critical statistic value 75.3447 68.52 37.4323* 47.21 17.9600 29.68 6.9127 15.41 0.4490 3.76 Table 2g Sector 6 Johansen tests for cointegration Trend: constant Sample: 1982 - 2010 maximum rank 0 1 2 3 4 5 parms 30 39 46 51 54 55 Number of obs = Lags = LL 337.85647 358.2123 368.71177 375.65743 379.94405 382.28019 eigenvalue . 0.75435 0.51524 0.38060 0.25594 0.14880 29 2 5% trace critical statistic value 88.8474 68.52 48.1358 47.21 27.1368* 29.68 13.2455 15.41 4.6723 3.76 Table 2h Sector 7 Johansen tests for cointegration Trend: constant Sample: 1982 - 2010 maximum rank 0 1 2 3 4 5 parms 30 39 46 51 54 55 June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK LL 370.51508 382.64727 393.51361 398.83227 402.22917 403.62435 Number of obs = Lags = eigenvalue . 0.56686 0.52735 0.30705 0.20885 0.09174 29 2 5% trace critical statistic value 66.2185* 68.52 41.9542 47.21 20.2215 29.68 9.5842 15.41 2.7904 3.76 22 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 Table 2i Sector 8 Johansen tests for cointegration Trend: constant Sample: 1982 - 2010 maximum rank 0 1 2 3 4 5 parms 30 39 46 51 54 55 Number of obs = Lags = LL 399.7938 410.13805 419.18136 424.82861 427.32992 429.25134 eigenvalue . 0.51002 0.46403 0.32258 0.15845 0.12411 29 2 5% trace critical statistic value 58.9151* 68.52 38.2266 47.21 20.1400 29.68 8.8455 15.41 3.8428 3.76 Results of Normalized Cointegrating Coefficients Table 3a Sector 0 Johansen normalization restriction imposed beta Coef. _ce1 realimports gniconstbill domprice impprice simpleavta~f _cons 1 -.6060141 .8931411 -1.993184 -.1693067 1.810574 Std. Err. . .0592761 .1284432 .1447514 .0414817 . z . -10.22 6.95 -13.77 -4.08 . P>|z| . 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 . [95% Conf. Interval] . -.7221931 .641397 -2.276891 -.2506093 . . -.4898351 1.144885 -1.709476 -.088004 . Table 3b Sector 1 Johansen normalization restriction imposed beta Coef. _ce1 realimports gniconstbill domprice impprice simpleavta~f _cons 1 -1.131859 -2.085972 2.856678 .1094989 .261836 Std. Err. . .1309922 .3314365 .1577977 .0112684 . z . -8.64 -6.29 18.10 9.72 . P>|z| . 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 . [95% Conf. Interval] . -1.388599 -2.735576 2.5474 .0874133 . . -.8751192 -1.436369 3.165955 .1315846 . Table 3c Sector 2 June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 23 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 Johansen normalization restriction imposed beta Coef. _ce1 realimports gniconstbill domprice impprice simpleavta~f _cons 1 -.9276013 -1.932647 2.936185 .6654426 -1.549599 Std. Err. . .0876075 .2743563 .4216616 .0850619 . z P>|z| . -10.59 -7.04 6.96 7.82 . . 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 . [95% Conf. Interval] . -1.099309 -2.470376 2.109743 .4987243 . . -.7558938 -1.394919 3.762626 .8321609 . Table 3d Sector 3 Johansen normalization restriction imposed beta Coef. _ce1 realimports gniconstbill domprice impprice simpleavta~f _cons 1 -.8279099 -1.237617 4.937531 1.296926 -8.292437 Std. Err. . .4080996 1.578216 1.463931 .3905323 . z P>|z| . -2.03 -0.78 3.37 3.32 . . 0.042 0.433 0.001 0.001 . [95% Conf. Interval] . -1.627771 -4.330864 2.068279 .5314964 . . -.0280493 1.85563 7.806782 2.062355 . Table 3e Sector 4 Johansen normalization restriction imposed beta Coef. _ce1 realimports gniconstbill domprice impprice simpleavta~f _cons 1 -.4917603 -7.264583 -6.746218 -3.38468 30.73145 Std. Err. . 2.016952 .9989268 5.327957 1.320966 . z P>|z| . -0.24 -7.27 -1.27 -2.56 . . 0.807 0.000 0.205 0.010 . [95% Conf. Interval] . -4.444913 -9.222443 -17.18882 -5.973726 . . 3.461393 -5.306722 3.696385 -.7956346 . Table 3f Sector 5 Johansen normalization restriction imposed beta Coef. _ce1 realimports gniconstbill domprice impprice simpleavta~f _cons 1 -3.087823 -7.801147 12.77593 .4926158 -4.475497 Std. Err. . .2341412 1.645763 2.420679 .19913 . z . -13.19 -4.74 5.28 2.47 . P>|z| . 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.013 . [95% Conf. Interval] . -3.546731 -11.02678 8.031487 .1023282 . . -2.628915 -4.575511 17.52038 .8829035 . Table 3g Sector 6 June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 24 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 Johansen normalization restriction imposed beta Coef. _ce1 realimports gniconstbill domprice impprice simpleavta~f _cons 1 -3.101338 30.65089 -26.91914 1.180727 -3.287551 Std. Err. z . .5490705 4.659498 4.642102 .2482223 . P>|z| . -5.65 6.58 -5.80 4.76 . . 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 . [95% Conf. Interval] . -4.177496 21.51844 -36.01749 .6942204 . . -2.025179 39.78334 -17.82079 1.667234 . Table 3h Sector 7 Johansen normalization restriction imposed beta Coef. _ce1 realimports gniconstbill domprice impprice simpleavta~f _cons 1 -3.239978 3.712937 1.654194 .107072 -5.643254 Std. Err. . .2745702 1.938091 .897383 .2681926 . z P>|z| . -11.80 1.92 1.84 0.40 . . 0.000 0.055 0.065 0.690 . [95% Conf. Interval] . -3.778126 -.0856527 -.1046447 -.4185758 . . -2.70183 7.511526 3.413032 .6327198 . Table 3i Sector 8 Johansen normalization restriction imposed beta Coef. _ce1 realimports gniconstbill domprice impprice simpleavta~f _cons 1 -2.854489 .6313831 -1.974583 -1.60409 9.299292 June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK Std. Err. . .5562836 1.47894 .6130574 .2347441 . z . -5.13 0.43 -3.22 -6.83 . P>|z| . 0.000 0.669 0.001 0.000 . [95% Conf. Interval] . -3.944785 -2.267286 -3.176154 -2.06418 . . -1.764194 3.530052 -.7730128 -1.144 . 25 2012 Cambridge Business & Economics Conference ISBN : 9780974211428 Table 4 : Coefficients of Tariff Rates for Each Sector Coefficient of Significance tariff level 0 -0.167 *** 1 0.11 *** 2 0.67 *** 3 1.3 *** 4 -3.38 *** 5 0.49 ** 6 1.18 *** 7 0.11 8 -1.6 *** Note: *,**,*** denote significance at 10 percent, 5 percent and 1 percent respectively. Sector Graph 1: Malaysian Manufactures Imports and Exports from 1990-2010 Source: World Development Indicator website June 27-28, 2012 Cambridge, UK 26