Impact of leadership on ICU clinician`s burnout ABSTRACT

advertisement

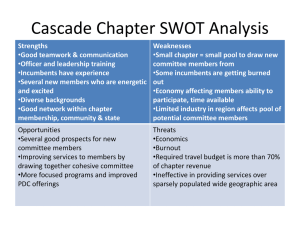

Impact of leadership on ICU clinician's burnout ABSTRACT Introduction: Global spreads of burnout among healthcare practitioners, particularly within intensive care units (ICUs), has been described as a growing crisis with a variety of unwanted consequences as drawbacks (1). Aim of the work: Our primary objective was to explore the prevalence of burnout in this area among different healthcare givers; we also focused on identifying the contributing factors as well as the role of empowerment and leadership impact. Methodology: We employed a cross-sectional descriptive study with purposive sampling. A combined methodological approach (quantitative and qualitative) was used with questionnaires. We used five instrument: Conditions of work effectiveness scale (CWES), Work stress scale (WSS), Maslasch Burnout scale (MBI-HSS), Leadership scale (LS), and Empowerment scale (ES). Results: We studied 200 healthcare practitioners within medical and surgical ICUs. The case study that focused on Qatari intensive care confirmed a high prevalence of burnout (25.5%), where physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists were equally at risk (p=0.19). Younger individuals were more likely to burn out (p=0.000). We report a high association of burnout with the instruments that we used. Both positive leadership and empowerment had a negative effect on burnout variance (12.4 and 3.8%, respectively) when considering practitioner burnout. Conclusion: The reported high burnout rate among practitioners in ICU settings necessitates special attention in terms of positive leadership attitudes; empowerment could serve as an ameliorating factor. Key words: burnout, ICU, practitioners Introduction Care of critically ill patients recognized as highly demanding and challenging profession, it requires extensive effort and communication between the staff during which professionals are exposed to variable degrees of work-related stress. Pressures related from financial demands as well as diagnostic, monitoring and therapeutic techniques put extra burden on intensive care unit (ICU) staff. According to Miller, et al., (1990 existence of stress and burnout in the workplace as well as related outlay affect many variable levels in the community. The ICU is one of the front lines in dealing with health care related crisis that could place the providers on variable degrees of psychological stress [1]. Staffing in ICU involved multiple specialties (physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, and clinical pharmacists), and dealing with these diversified practitioners is a difficult task that needs knowledge, skills and proper communication [2]. In an attempt for ICU leaders to get higher performance, burnout problem needs to be looked at with special attention as prophylaxis is better than treatment in medicine and it seems that having burnout oriented field with tools for the early management seems to be attractive goal. It is reasonable that leader empowerment of the staff could have a positive impact on the overall progress, execution and engagement at work. Burnout could be presented with irritability, insomnia, feeding problems and depressive attitude as well as increased leave requests among staff. Low performance at workplace and high resigning intentions could be attributed to emotional exhaustion. Job satisfaction depends on work and organization; the former is related to workload, social backup, and autonomy while the latter is related to authority and decision-making. Individual characters, work conditions as overload, feeling of valueless job, and disputes predispose to burnout [3]. Linkage between emotional stress and burnout exist as expressed in a study conducted in UK physicians, higher stress associates higher emotional exhaustion. Emotional tiredness, depersonalization, and reduced personal and professional achievements characterized the burnout. The high association in healthcare may result 2 from daily management of complex, stressful situations and intense interpersonal relations [4]. The decision-making could involve conditions of life and death as well as withdrawing and withholding life supportive measures. Staff retention is another risk factor. Nurses are more exposed to burnout than physicians, at least one-third experienced severe burnout syndrome symptoms at certain time. Burnout could be attributed to conflicts at workplace between practitioners and younger age of the practitioners is more susceptible [5]. According to Aiken, et al., (2002) different forms of leadership may be required through professional career development, however complexity in the leadership and burnout relation exists. Protection against the depersonalization could be attributed to transformational leadership [6]. Stress released from the physical and social factors as well as vagueness of roles, but leadership management could significantly lead to increased emotional exhaustion levels. [7]. Leader-empowering attitude significantly enhanced staff approach to empowerment structures that is linked with reduction of the encountered job tension and enhancement of work effectiveness [8]. Nurses working with sounding leaders got significantly lower levels of emotional exhaustion and associated stress, and they got also preferable communication with physicians, superior satisfaction with their leaders and their jobs, which reflected on improvement of patient care demands than did nurses working for discordant leaders [9]. Empowerment as a factor in burnout, that latter affects attraction and retention of the experienced health care staff. Positive work environments rely heavily on the leaders who heavily influence medical staff performance and response to working conditions as well as the quality of care supplied to the customers. Empowerment techniques seem to offer the staff more satisfaction as sharing in decision making, enhancing the work value, facilitating target achievements, trusting high execution, and releasing bureaucratic boundaries to have more autonomy. Leader empowering attitude involved adequate control in terms of clear roles and responsibilities, 3 adequate reward system, fairness and conformity between organization and employee's needs [10]. Empowerment is hypothesized to improve nurses and patients capabilities to convey their requirements that could manage their lives [11]. Wise & Billi (1995) mentioned that implementing, work support methodology should involve clinical leaders to carry the organizational or the governmental messages through endorsing and adopting guidelines in the regional or local circumstances [12]. Objectives of the study This study predominates at investigating the burnout problem which is poorly estimated in health care; the author aim at the present study the prevalence of burnout within the intensive care settings in a particular institution, and whether the leadership attitude could increase or ameliorate the problem. As well the effect of participant empowerment on ameliorating this condition will be considered. Methodology Settings This study conducted in two intensive care units (ICU), in a tertiary hospital in the Middle East. The number of beds in each ICU was 20 and 12 respectively. The participants were screened for socio-demographic data such as age, gender, profession, marital state, education, native country, years of experience, weekly working hours and salary. The questionnaire were clarified to the potential respondents in order to clear any poor understanding. English used as the official language in the organization; translation of the used instruments to individual mother languages is not required. Design Cross-sectional descriptive survey with purposeful sampling. Mixed qualitative and quantitative methodology used in this dissertation. Invitations to participate through the corporate mail, anonymous questionnaire survey were presented to the staff members including physicians, nurses and respiratory therapists who work as full time. Instrumentation 4 The used instrumentation is questionnaire that is divided into the following sections: A) Condition of work effectiveness questionnaire (CWEQ): This scale consisted of 19 items developed by Kanter, (1977) measured by a 5 point Likert type response [13]. B) Occupational stress scale (WSS): A three-point scale was used in which low stress = 1, moderate stress = 2, and extreme stress = 3. The total number of declaration in the scale will be 15 [14]. C) Maslach Burnout Inventory human services survey (MBI-HSS): The scale is a standardized instrument to measure burnout it utilize 9 items related to emotional exhaustion and it is most frequently used in health care researches, the nine items are calculated to get the whole score, scores of 27 and more signaled high burnout [15]. The percentage of high degree of burnout was used for advanced analysis. We got permission to use this scale from (Mindgarden.com, USA). D) Psychological Empowerment Scale (ES): A 12 items scale considering work meaning, efficiency, autonomy, and impact (Spreitzer, 1995). Each of the preceding four components is measured by three items through 7 point Likert scale ranging from very strong disagreement (1 point) to very strong agreement (7 points). Calculating the total 12 items to get the total Psychological Empowerment score. [16].E) Leadership Behaviours scale (LS): The staff discernment of managers’ leadership attitude were measured using the 11 item Manager Action Scale. [17]. The questionnaires were submitted in English form; no need for translation, as health care practitioners in the organization, must practice English that is the official language at workplace. The results of the analysis will be presented using descriptive methods. The quantitative and qualitative data will be analyzed statistically, the relations between the variables will be interpreted, the relation between burnout score and socio-demographic variables, occupational stress score, and empowerment scale will be assessed statistically using (t-test, analysis of variance, correlation efficient and regression). Ethical Considerations: Participant identity kept confidential, final report would not contain any identity. Comprehensive explanation for the participants about the questionnaires, the type, purpose of the study and outcome was done, early rejection, or late withdrawal was permissive. Ethical approval was obtained according to the corporate regulations. The ethical consent 5 attached after being approved from university of Liverpool and medical research center. IRB Approval 14281/14 by HMC research center. Data Collection Procedures The purpose of the study was explained to the managing directors in the hospitals. Clarifying the study to managers of the units after initial hospital authorization was procured. The questioners (appendix A) were driven through the corporate mail to the respondents. Survey-Monkey was used to deliver the questioners and to receive the responses. The questioners composed of 5 sections (Appendix A). Statistical analysis Data were presented as mean ± SD for quantitative data and frequency and proportion for qualitative data. Median and range were calculated for non-normal continuous distributed data. Statistical significance tests included: For quantitative data, the student's ttests and Mann-Whitney U tests (if data is not non-normally distributed); and Chi-square tests for categorical variables. A P-value of <0.05 (two tailed) was considered the statistical significant level. Multivariate regression analysis performed for significant data in a univariate analysis, both within group agreement (rwg) and interclass correlation (ICC) assessed. Individual data could not be aggregated to the level of the group if rwg median equal or was less than 0.7. Variability between the groups should be higher that variability within groups (James, Demaree, & Wolf, 1984). Clinical and laboratory data was entered into a database (Microsoft Excel 2013, Redmond, WA, USA) and statistical analyses performed (SPSS Inc., Version 21. Chicago IL, USA). Results Descriptive Statistics The participant's background initially determined all were health care practitioners highly educated. Then the contents were transferred to statements. The validity was established through face validity where questionnaires intention of measurement was addressed, making sure it represent the contents, appropriate for the studied population, and appearance of the instrument look like a questionnaire [18]. A pilot test including 20 subjects who not enrolled in study sample was tested to check the reliability of the questionnaires, the collected data were analyzed by SPSS [18]. Missing Data 6 The missing data managed statistically; it comprised less than 6% for all scales and most in demographic variables. The “highest degree” was the main missing variable in the demographics ad it was missing 4% of the time.” No specific missing pattern identified after examination with t-test and Chi-square. Questionnaires were distributed to 390 health care practitioners including physicians, nurses and respiratory therapists working on two inpatient medical and surgical intensive care units. Two hundred practitioners completed and returned the questionnaires, for a 51.8% response rate. The response rates for all participating units reached 200 participants, which was the desired target. The mean ageSD of the participants was 36.36.7, the rest of the demographic characteristics were shown in (table 1) Validity and reliability of the questionnaires The validity of the five used instruments demonstrated in previous literatures. However, the design of the survey included a blend of the instruments for which validity needed to confirmation. Reliability is tested by Cronbach’s alpha and ICC. Adequate ICC is .72 but .8 is preferred denoting high-reliability level. The mean rwg (in group agreement) was 0.827 denoting adequate intergroup aggregation above ICC was .60 and the rwg was .70, the instrument was considered to be in composition form [19]. Individual data distribution The distribution of individual data for the MBI-HSS used instrument was examined to and found to have normally distribution (Figure 1) accordingly parametric statistics were suitable. Statistical test of hypothesis The prevalence of burnout in ICU staff is high in our study, we found that 51 respondents (25.5%) suffered a high degree of burnout, while 29 respondent (14.5%) suffered moderate degree of burnout The only significant relation was encountered with the gender distribution (table 3). 7 The relation between Maslach burnout score for human social services and the rest of the other used instruments was studied using Pearson correlation (table 4). We found significant correlation with age (p=0.000), CWES (p=0.008), WSC (p=0.000), ES (p=0.006), and LS (p=0.000) by 2-tailed test. Linear regression was attempted to draw relation between burnout measured by MBI and work condition subscale (table 5), where significant predictors for burnout accordingly were item 1 (challenging work) p=0.001, item 14 (seeking out ideas from professionals other than physicians) p=0.029, and item 6 (goals of management) p= 0.033. The r2 for this model was 0.309 thus work related conditions account for 37.9% of the variation in burnout. Linear regression was attempted to draw relation between burnout measured by MBS and leadership subscale, where no significant predictors for burnout among the subscale. Next the leadership influence on high burnout was studied with linear path analysis with burnout measured by MBI as an outcome variable and leadership as a predictor variable. The path coefficient was .35 (p<.001). The result was statistically significant, however, r2 was .124, indicating that leadership accounted for only 12.4% of variance in practitioners burnout (figure 2) Linear regression was attempted to draw relation between MBS and empowerment subscale (table 7), where significant predictors for burnout accordingly were item 4 (My impact on what happens in my department is large) p=0.004, and item 2 (The work that I do is important to me) p=0.048. Next the empowerment influence on high burnout was studied with linear path analysis with burnout as an outcome variable and empowerment as a predictor variable. . The path coefficient was .35 (p<.006). The result was statistically significant, however, r2 was .038, indicating that leadership accounted for only 3.8% of variance in practitioners burnout (figure 3). Discussion The salient findings of this study are: high prevalence of burnout found in the Qatari ICU settings and it is below the international levels. Respiratory therapists similarly got burnout as the rest of the critical care practitioners. Higher burnout found in males according to our results. We noted involvement of Syrian nationality more with high burnout and more burnout in medical ICU. We observed higher level of burnout in the younger age population. 8 Strong relations between the used instruments and high burnout including work condition, work stress, leadership and empowerment scales were found in our work. Among the condition at work items challenging work, and goals of management were strong burnout predictors among the work conditions scale. Positive leadership attitude had the negative effect on high burnout, where leadership accounted for only 12.4% of the variance in practitioner's burnout. Burnout term is a psychological one associated with reduction of the work interest in certain situations after experiencing long-term exhaustion. Lack of recover after disbursing too much effort in work could be the striking. Healthcare practitioners are vulnerable to burnout, especially in areas with more stress [20]. The ICU pattern of work could typically lead to burnout which is reflected on health care practitioners well-being and work performance. Retention of the caregivers could be affected to a greater extent and leaders in health care organizations suffer from a shortage in ICU staff that threatens the given services [21]. Poncet et al. (2007) reported high association of burnout symptoms in ICU staff; where up to 45% of the practitioners got burnout symptoms that vary from insomnia, to irritability up to the blown full picture of depression [22]. This aim of this study was to discover prevalence of burnout within the ICU in Qatar, find the precipitating demographics and working conditions for burnout, and to explore the influence of leadership as well as empowerment on burnout. Two hundred participants were involved in this study, where questionnaires were distributed to 390 health care practitioners including physicians, nurses and respiratory therapists form two ICUs (table 1). Demographics We found that 51 respondents (25.5%) suffered a high degree of burnout with higher association in physicians (table 3). In a multicenter study conducted in France Embriaco, et al., (2007) reported high level of burnout in more than have of the physicians and one third of the nurses working in ICUs suffered the same phenomena [20]. Respiratory therapists suffer the same stressors as other health care practitioners but only few studies addressed the association of burnout in this group [23]. 9 Guntupalli et al., (2014) reported 25% severe burnout in respiratory therapist in USA [24]. Similarly Shelledy, et al., (1992) went through stress in ICU professionals, and find that this group suffered burnout as the rest of the ICU staff where leader recognition of these factors is needed for enhancing retention [25]. Few studies went through healthcare burnout in the Middle East [26, 27] but no studies went through in Qatari ICU settings where practitioners are vulnerable to stressors. All respondents in our study were non-Qatari practitioners. Similarly in Saudi Arabia study that share similar demographics with the rest of the Gulf countries most of the nursing workforce is from other countries that enhance the work related stress [26]. Close to Qatar in an Egyptian cross-sectional survey targeting physician burnout, the authors find that 62.2% of their studied population suffered experienced emotional exhaustion, 56.1% had depersonalization, and 58.2% got reduced individual capacity. Egypt got different demographics from the Gulf group where lacks of job support and salary dissatisfaction were the strongest predictors in this study [27]. Abdulla, Al-Qahtani & Al-Kuwari (2011), studied burnout in Qatar but in general health practitioners. The authors found level of high burnout about 12.5% that was below the international level, however Qatari physicians suffered the high incidence of burnout syndrome than other population in same study [28]. In our study males got higher burnout than females (table 3). Embriaco, et al., (2007a) found high level in ICU women [20], similarly Abdulla, Al-Qahtani & AlKuwari (2011), found higher burnout in female primary physicians [28]. Variable level of high burnout reported in the diverse population and different population. We encountered higher level of burnout in physicians (35.4%) followed by respiratory therapists (25%) followed by nurses (19%). The Syrians suffered the highest burnout percentage (table 4). The influence related to specific nationality could differ the evolvement of burnout Al-Turki et al., (2010) found that non-Saudi nurses were significantly more susceptible to emotional 10 exhaustion (27.3 ± 12.1 versus 21.6 ± 2.9) than Saudi nurses [26]. Syrians suffer from civil war since 3 years which could add to the faced stressors. High burnout was more in younger age groups 25-34 than older groups. People who got lower years of professional experience (less than five years) experienced high degree of burnout (57.1%) than professionals with more years of experience (table 3). High degree of burnout had high significant relation p=0.000 with the lower age group by Pearson relation (table 4). This was similar to the results of Abdulla, AlQahtani & Al-Kuwari (2011) who find higher burnout in younger professionals [28]. Age less than 30 years was in a multicenter European study was significantly associated with high burnout [21]. But on the other hand the study of Koivula, Paunonen & Laippala, (2000) indicated that burnout increases with age [29]. High burnout was equally distributed in participants with variable years of experience within the same organization 25% each in our study. However, Koivula, Paunonen & Laippala, (2000) reported lower level of burnout in practitioners with shorter work experience [29]. Furthermore in a more recent study managerial situation and years of experience did not impact burnout [30], this was concomitant to findings of Merlani, et al., (2011), where years of experience in ICU did not affect the burnout association [21]. Participants with higher level of had higher burnout than those with lower level of education but it did not reach statistical significance. Koivula, Paunonen & Laippala, (2000), reported experience of high burnout level in participants with a secondary education level laboring on psychiatric wards. The authors also found that continuous professional education could ameliorate the burnout level [29]. Similarly Zaghloul & El Enein, (2009), found that higher educational level suffered more burnout among practitioners. Perhaps the demands and social support is higher in the later group [31]. Unmarried participants in our study were more involved in higher burnout than the married one. This was consistent with findings of Keane, Ducette & Adler (1985), but 11 the authors were able to identify significantly high burnout in unmarried nurses [32]. No major differences encountered in our study related to satisfaction with the salary where high burnout with more in unsatisfied than satisfied participants (57% versus 48.5%). Houkes, et al., (2001) emphasized that low salary lower employees satisfaction [33]. The last contrast was related to working unit we found that participants who work in medical ICU are more involved in high burnout than who work in surgical ICU (30.2% versus 18.5%). Guntupalli et al., (2014) also found higher percentage of burnout in medical ICU when compared with the surgical. In our settings this could be explained by higher workload and more difficult to manage patients [24]. The only significant relation was encountered with the gender distribution (Table 3). High burnout relations with other score The Pearson correlation between Maslach burnout score for human social services and the rest of the other used instruments contained in (Table 4). We found significant correlation with age, CWEQ, WSC, ES, and LS by 2-tailed test. In our study lower score of CWEQ, was significantly associated with increase burnout, and this was statistically significant . Consequently, working conditions that allow data access, and resources as well as formal and informal empowerment could guard against the development of burnout syndrome. Kinzl, et al., (2005) mentioned that control over work conditions had a positive impact on practitioner's satisfaction [34]. However, in our study work condition were not the only influential factors for burnout. This was proportionate with finding of Lederer, et al., (2006) who indicated that job conditions and work environment contribute more than personality structure in the development of burnout [35]. Great importance had been attributed to changing of the work conditions in ameliorating burnout which act better than behavioral prevention in terms of advocating healthy behavior of the individual [36]. To identify the predictors for burnout among the condition at work linear regression was done between burnout measured by MBI and condition at work 12 effectiveness (table 5), where significant predictors for burnout accordingly were item 1 (challenging work), item 14 (seeking out ideas from professionals other than physicians), and item 6 (goals of management). Work related conditions account for 37.9% of the variation in burnout. According to Houkes, et al., (2001) it is possible to predict the outcome of stress and burnout when work conditions and characteristics are recognized [33]. On the other hand, challenging work assignments could be associated with the higher workload [37]. Physician burnout was studied by Gundersen, (2001) who confirmed that characters of the work that make it challenging as autonomy, social contacts and skill variation influence intrinsic work motivation. Emotional exhaustion could evolve with aspects of work demands, loss of social support [38]. The second instrument used in our study was the WSS. According to. In our study high burnout was significantly related to work stress scale. Zaghloul (2008), found that privacy inadequacy, shortage of staff, excess workload, fluctuation in workload, patient difficult to manage are the high initiating factors in this scale [14]. Zaghloul & El Enein (2009), found that health care practitioners suffered from stress exposure regardless of the organizational and hierarchical structure. Stress reduction and resources coping should be undertaken to reduce burnout. Job security and occupational health education seems to do better in this context [31]. According to Zaghloul (2008), the basic element for staff burnout is the workload which eventually could lead to increasing turnover. The used scale could be convenient as it is short reliable and could be used as a valuable tool for managers [14]. A statistical significant relation was found between leadership and burnout by tvalue for a Pearson correlation (table 4). The growing demands for decisions and actions in health care on robust evidence basis require promoting the staff autonomy seems to be a perfect goal. Al-Hamdan et al., (2013) mentioned that leaders decisions and organizational pursuit based on scientific evidence. Leadership scale looks to be usable to the Jordanian settings [17]. 13 Linear regression was attempted to draw relation between burnout measured by MBS and leadership subscale, where no significant predictors for burnout among the subscale (Table 6). Encouraging practitioner through certain action that promote autonomy was a high predictor for reducing burnout in Al-Hamdan et al., (2013) study [17]. Delegating 24-hours responsibility in decision-making in variable situations was noted. This was also similar to the report of Abdullah & Shaw (2007) who concluded that better outcome could be achieved with participative decisionmaking especially when practitioners got involved in capital planning which in turn enhance the given autonomy [39]. Also there is no identical study summarized the effect of leadership on burnout in different health care practitioners, Greco et al., (2006) found that leaders’ behaviors had an indirect effect on lowering emotional exhaustion and possible burnout [40]. Next the leadership influence on high burnout was studied with linear path analysis with burnout measured by MBI as an outcome variable and leadership as a predictor variable which statistically significant. However, r2 was .124, indicating that leadership accounted for only 12.4% of the variance in practitioners burnout (figure 2). Leaders perceived by the followers as the prominent individuals in the organizational environments. The practice of leaders makes a difference in the occurrence of burnout and got implications as well in its prevention (Stordeur, D'hoore & Vandenberghe, 2001). Close to our results is the multivariate analyses done by the authors, they found that more variation in emotional exhaustion is more likely to be explained by work stressors than with dimensions of leadership (22% vs. 9%). Work stressors identified were physical environments, social environments and role obscurity. [41] Empowerment had been defined as intrinsic task motivation in the work stings, so empowering symbolized by energizing, where tasks are basic targets, external circumstances and subjective interpretation (Thomas and Velthouse, 1990). Here is existing worldwide utilization of empowerment with variable tools and strategies [42]. 14 In a landmark study in health care was done by Laschinger et al., (2003) who tested the work empowerment predictive power for burnout in nurses [8]. They found direct empowerment effect on emotional exhaustion. In our study, we did linear path analysis with burnout as an outcome variable and empowerment as a predictor variable. We got significant relation where path coefficient was .35 (p<.006). However, r2 was .038, indicating that leadership accounted for only 3.8% of variance in practitioner's burnout (figure 3). Multiple achievements had been reported due to empowerment including decreased work Fewer manifestations of burnout and reduced leave days stress (Wåhlin, Ek & Idvall, 2010) [43], enhanced work satisfaction and commitment at work area (Kuokkanen, Leino-Kilpi & Katajisto, 2003)[44] and efficiency (Laschinger et al., 2001) [45]. Linear regression was attempted to draw relation between MBS and empowerment subscale (Table 7), to find the significant predictors for burnout, we found statistical relation with item 4 (My impact on what happens in my department is large) , and item 2 (The work that I do is important to me). Greco, Laschinger & Wong (2006), noted that strategies to enhance involvement and decrease burnout are essential improving work environments [40]. The later needed to be pushed by the leaders, which is reflected on the quality of care. Laschinger et al. (1999) concluded that empowering attitude by the leaders like boosting the work meaning, decision making involvement, smooth target achievements, providing autonomy, hasten bureaucratic boundaries and expressing confidence in high performance were associated with increased feelings of empowerment by practitioners in critical care settings [9]. Our results were similar to Kuokkanen, Leino-Kilpi & Katajisto, (2003) who found that strengthening and empowering ICU staff could be raised when there is feeling of doing something good suggesting the possible benefit from overwhelming prevention on basis of support and enabling good leadership [44]. Study limitation 15 A limitation of this study is a single center, done only in a single country. The number is relatively limited. A survey covering different organizations within the same territory or different countries could yield a better outcome. Conclusion: The reported high burnout rate among practitioners in ICU settings necessitates special attention in terms of positive leadership attitudes; empowerment could serve as an ameliorating factor. Further studies are required to countenance our findings in the same region and individual groups. List of abbreviations CWEQ: Condition of work effectiveness questionnaire; ES: Psychological Empowerment Scale; ICU: intensive care unit; LS: Leadership Behaviours scale: LS; MBI-HSS: Maslach Burnout Inventory human services survey; WSS: Occupational stress scale: Recommendation for future research: Key messages: 1) Prevalence of high burnout in Qatari ICUs. 2) Work empowerment could be utilized in this context. 3) High burnout relation with the leadership, empowerment, and work conditions, 4) Specific managerial action could ameliorate the resulting burnout. References 1) Miller KI, Ellis BH, Zook EG & Lyles JS. An integrated model of communication, stress, and burnout in the workplace. Communic Res. 1990; 17(3), 300-326. 16 2) Saini R, Kaur S & Das K. Assessment of stress and burnout among intensive care nurses at a tertiary care hospital. J Men Health Hum Beh. 2011; 16(1), 43-48. 3) Myhren, H., Ekeberg, Ø., & Stokland, O. Job satisfaction and burnout among intensive care unit nurses and physicians. Crit Care Res Prac. 2013; 2013: 786176. 4) McManus IC, Winder BC & Gordon D. The causal links between stress and burnout in a longitudinal study of UK doctors. Lancet 2002; 359(9323), 2089-2090. 5) Teixeira C, Ribeiro O, Fonseca AM & Carvalho AS. Burnout in intensive care units-a consideration of the possible prevalence and frequency of new risk factors: a descriptive correlational multicentre study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2013; 13(1), 38. 6) Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski JA, Busse R, Clarke H & Shamian J. Nurses’ reports on hospital care in five countries. Health affairs. 2001; 20(3), 43-53. 7) Stordeur S, D'hoore W & Vandenberghe C. Leadership, organizational stress, and emotional exhaustion among hospital nursing staff. J Adv Nurs. 2001; 35(4), 533542. 8) Laschinger HKS, Wong C, McMahon L & Kaufmann C. Leader behavior impact on staff nurse empowerment, job tension, and work effectiveness’. J Nurs Adm.1999; 29(5), 28-39. 9) Cummings G, Hayduk L & Estabrooks C. Mitigating the impact of hospital restructuring on nurses: the responsibility of emotionally intelligent leadership. Nurs Res. 2005; 54(1), 2-12. 10) Greco, P., Laschinger, H. K. S., & Wong, C. (2006). 'Leader empowering behaviours, staff nurse empowerment and work engagement/burnout'. Nursing Leadership, 19(4), 41-56 [Online]. 11) Gibson CH. A concept analysis of empowerment. J Adv Nurs. 1991; 16(3), 354-361. 12) Wise CG & Billi JE. A model for practice guideline adaptation and implementation: empowerment of the physician. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1995; 21(9), 465-476. 13) Kanter RM. Men and women of the corporation. A Division of Harper Collins Publishers.1977;5049 14) Zaghloul AA. Developing and validating a tool to assess nurse stress’. The J Egypt Public Health Assoc.2007; 83(3-4), 223-237. 15) Maslach C, Jackson SE & Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Palo Alto, California. 1996; 3rd Ed 16) Spreitzer, G. M. (1995). ‘Psychological empowerment in the workplace: Dimensions, measurement, and validation’. Academy of manage Journal,38(5), 1442-1465 [Online]. 17) Al-Hamdan Z, Bawadi H, Bawadi H & Mrayyan MT. Nurse Managers’ Actions (NMAs) Scale to Promote Nurses’ Autonomy: Testing a New Research Instrument. Int J Humanities Soc Sci. 2013; 3(8), 271-278 18) Radhakrishna RB. Tips for developing and testing questionnaires/instruments. J Exten. 2007; 45(1), 1-4. 19) Klein KJ & Kozlowski SW. Multilevel theory, research, and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions. Jossey-Bass; 2000. 20) Embriaco N, Azoulay E, Barrau K, Kentish N, Pochard F, Loundou A & Papazian L. High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2007; 175(7), 686-692. 21) Merlani P, Verdon M, Businger A, Domenighetti G, Pargger H & Ricou B. Burnout in ICU caregivers: a multicenter study of factors associated to centers. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2011; 184(10), 1140-1146. 22) Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, Timsit JF, Pochard F & Azoulay E. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing. Am J Resp Crit Care Med.2007; 175(7), 698-704 [Online]. 23) Hoffman LA, Happ MB, Scharfenberg C, DiVirgilio-Thomas D & Tasota FJ. Perceptions of physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists about the role of acute care nurse practitioners. Am J Crit Care 2004; 13(6), 480-488 [Online]. 17 24) Guntupalli KK, Wachtel S, Mallampalli A & Surani S. Burnout in the intensive care unit professionals. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2014; 18(3), 139 [Online]. 25) Shelledy DC, Mikles SP, May DF & Youtsey JW. Analysis of job satisfaction, burnout, and intent of respiratory care practitioners to leave the field or the job. Resp Care. 1992; 37(1), 46-60. 26) Al-Turki HA, Al-Turki RA, Al-Dardas HA, Al-Gazal MR, Al-Maghrabi GH, AlEnizi NH & Ghareeb BA. Burnout syndrome among multinational nurses working in Saudi Arabia. Ann Afr Med. 2010; 9(4). 27) Shams T & El-Masry R. Job Stress and Burnout among Academic Career Anaesthesiologists at an Egyptian University Hospital’. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2013; 13(2), 287. 28) Abdulla L, Al-Qahtani DM & Al-Kuwari MG. Prevalence and determinants of burnout syndrome among primary healthcare physicians in Qatar. South Afr Fam Prac. 2011; 53(4), 380-383. 29) Koivula M, Paunonen M & Laippala P. Burnout among nursing staff in two Finnish hospitals. J Nurs Manage. 2000; 8(3), 149-158 . 30) Ilhan MN, Durukan E, Taner E, Maral, I & Bumin MA. Burnout and its correlates among nursing staff: questionnaire survey. J Adv Nurs. 2008; 61(1), 100-106. 31) Zaghloul AA & El Enein NYA. Nurse stress at two different organizational settings in Alexandria. J Multidiscip Healthc.2009; 2, 45. 32) Keane A, Ducette J & Adler DC. Stress in ICU and non-ICU nurses. Nurs Res 1985; 34(4), 231-236 [Online]. 33) Houkes I, Janssen PP, de Jonge J & Nijhuis FJ. Specific relationships between work characteristics and intrinsic work motivation, burnout and turnover intention: A multi-sample analysis. Europ J Work Organiz Psychol. 2001; 10(1), 1-23. 34) Kinzl JF, Knotzer H, Traweger C, Lederer W, Heidegger T & Benzer A. Influence of working conditions on job satisfaction in anaesthetists’. Br J Anaesth. 2005; 94(2). 35) Lederer W, Kinzl JF, Trefalt E, Traweger C & Benzer A. Significance of working conditions on burnout in anesthetists. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2006; 50(1), 58-63. 36) Ramirez AJ, Graham J, Richards MA, Gregory WM & Cull A. Mental health of hospital consultants: the effects of stress and satisfaction at work. Lancet. 1996; 347(9003), 724-728. 37) Janssen PP, De Jonge J & Bakker AB. Specific determinants of intrinsic work motivation, burnout and turnover intentions: a study among nurses. J Adv Nurs. 1999; 29(6), 1360-1369. 38) Gundersen L. Physician burnout. Ann Intern Med. 2001; 135(2), 145-148. 39) Abdullah MT & Shaw J. A review of the experience of hospital autonomy in Pakistan. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2007; 22(1), 45-62 [Online]. 40) Greco P, Laschinger HKS & Wong C. Leader empowering behaviours, staff nurse empowerment and work engagement/burnout. Nurs Leadersh 2006; 19(4), 41-56. 41) Stordeur S, D'hoore W & Vandenberghe C. Leadership, organizational stress, and emotional exhaustion among hospital nursing staff. J Adv Nurs. 2001; 35(4), 533542. 42) Thomas KW & Velthouse BA. Cognitive elements of empowerment: An “interpretive” model of intrinsic task motivation. Academy Manage Rev. 1990; 15(4), 666-681. 43) Wåhlin I, Ek AC & Idvall E. Staff empowerment in intensive care: nurses’ and physicians’ lived experiences. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2010; 26(5), 262-269. 44) Kuokkanen L, Leino-Kilpi H & Katajisto J. Nurse empowerment, job-related satisfaction, and organizational commitment. J Nurs Care Qual. 2003; 18(3), 184192. 18 45) Laschinger H.K.S., Finegan J., Shamian J. & Wilk P. (Impact of structural and psychological empowerment on job strain in nursing work settings’. J Nurs Adm. 2001; 31, 260–272. 19 Variable (s) Age Gender Marriage Years in profession Years in the hospital Years in the unit Working unit Highest education Profession Salary Satisfaction Description Range 26 Minimum-Maximum 25-51 Mean SD 36.36.7 Female 109 (54.5) Male 89 (45.5) Married 144 (72.5) Unmarried 55 (27.5) Range 24 Minimum-Maximum 1-25 Mean SD 10.516.2 Range 14 Minimum-Maximum 1-15 Mean SD 4.36.6 Range 13 Minimum-Maximum 1-14 Mean SD 2.83.2 Medical 106 (53) Surgical 65 (32) Both 26 (13) Diploma 48 (24) Bachelorette 97 (48.5) Master or higher 49 (24.5) Physician 65 (32.5) Nurse 96 (48) Respiratory therapist 28 (14) Strongly agree 6 (3) Agree 29 (14.5) Neither agree or disagree 77 (38.5) 20 Disagree 80 (40) Strongly disagree 6 (3) Table 1. Demographic variables among the studied group Reliability Validity Cronbach’s alpha ICC Rwg CWES .815 to .828 .83 0.61 WSS 704 to .785 .756 0.608 MBI-HSS 849 to .905 .899 1.57 LS 879 to .907 .881 .979 ES 815 to .896 .879 1.014 Table 2) Reliability and validity and r of the used instruments Adequate ICC is .72 but .8 is preferred denoting high-reliability level. The mean rwg (in group agreement) was 0.827 denoting adequate intergroup aggregation Based on the criteria, if the ICC was .60 and the rwg was .70, the instrument was considered to be in composition form. (Klein & Kozlowski, 2000) 21 High Burnout Moderate burnout Mild or no burnout Pvalue 0.229 Number (%) Age (years) 25-34 18 (25.4) 14 (19.7) 39 (54.9) 35-44 31 (26.7) 15 (12.9) 70 (60.3) 45-54 2 (15.4) 0 11 (84.6) Less than 5 years 8 (57.1) 2 (14.3) 4 (28.6) 5-10 years 28 (25.2) 17 (15.3) 66 (59.5) 11-15 9 (18.4) 8 (16.3) 32 (65.3) More than 15 6 (23.1) 2 (7.7) 18 (69.2) Less than 5 years 41 (25.5) 23 (14.3) 97 (60.2) More than 5 years 10 (25.6) 6 (15.4) 23 (59) Less than 3 years 34 (22.8) 25 (16.8) 90 (60.4) More than 3 years 16 (32.7) 4 (8.2) 29 (59.2) 0.193 Female 22 (20) 21 (19.1) 67 (60.9) 0.049 Male 28 (31.5) 8 (9) 53 (59.6) Married 34 (23.6) 19 (13.2) 91 (63.2) Unmarried 17 (30.9) 9 (16.4) 29 (52.7) Egyptian 8 (28.6) 5 (17.9) 15 (53.6) Indian 13 (16.2) 12 (15) 55 (68.8) Philippine 14 (26.9) 7 (13.5) 31 (59.6) Syrian 7 (43.8) 1 (6.2) 8 (50) Years of profession 0.107 Years within organization 0.983 Years within unit Gender Marital state 0.4 Nationality 0.29 22 Others 9 (37.5) 4 (16.7) 11 (45.8) Baccalaureate degree 28 (28.9) 16 (16.5) 53 (54.6) Diploma 8 (16.7) 9 (18.8) 31 (64.6) Master 14 (28.6) 4 (8.2) 31 (63.3) Medical CCU 32 (30.2) 16 (15.1) 58 (54.7) Surgical CT-ICU 12 (18.5) 10 (15.4) 43 (66.2) Both 5 (19.2) 2 (7.7) 19 (73.1) Physician 23 (35.4) 8 (12.3) 34 (52.3) Nurse 19 (19.8) 15 (15.6) 62 (64.6) Respiratory therapist 7 (25) 2 (7.1) 19 (67.9) Agree 17 (48.5) 5 (14.2) 13 (37.1) Neither agree or disagree 23 (29.8) 11 (14.2) 43 (55.8) Disagree 58 (57) 13 (15.1) 15 (17.4) Highest education level 0.289 Working unit 0.277 Profession 0.191 Salary satisfaction 0.46 Table 3. Burnout distribution among the studied group 23 Variable MBS Sig. (2-tailed) Age Pearson Correlation -.466** .000 CWES Pearson Correlation -.186** .008 WSS Pearson Correlation .469** .000 ES Pearson Correlation -.196** .006 LS Pearson Correlation -.353** .000 *. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).. Table 4. Burnout relation to the other scores and age. 24 Standardized t Sig. 95.0% Confidence Interval for B Coefficients Beta Lower Bound Upper Bound stress1 .270 3.335 .001 2.306 9.040 stress2 .009 .121 .904 -2.790 3.153 stress3 -.005 -.051 .959 -3.240 3.076 sresss4 .159 1.814 .072 -.268 6.133 stress5 -.103 -1.182 .240 -5.765 1.455 stress6 .194 2.159 .033 .282 6.497 stress7 -.020 -.223 .824 -3.404 2.716 stress8 .089 .958 .340 -1.750 5.032 stress9 -.001 -.014 .989 -3.970 3.915 stress10 .063 .618 .538 -2.560 4.883 stress11 .179 1.951 .053 -.051 7.144 stress12 -.048 -.595 .553 -3.404 1.831 stress13 -.174 -1.974 .051 -6.370 .008 stress14 .194 2.211 .029 .325 5.895 Table 5. Relation between work condition subscales and burnout 25 Standardized t Sig. 95.0% Confidence Interval for B Coefficients Beta Lower Bound (Constant) Upper Bound 8.768 .000 30.567 48.336 leader1 .013 .141 .888 -2.447 2.823 leader2 -.138 -1.325 .187 -4.965 .977 leader3 -.005 -.047 .962 -2.290 2.183 leader4 -.020 -.184 .854 -3.270 2.711 leader5 -.147 -1.242 .216 -4.977 1.133 leader6 .014 .132 .895 -2.649 3.030 leader7 -.068 -.514 .608 -4.173 2.450 leader8 -.130 -.963 .337 -4.914 1.692 leader9 -.046 -.441 .660 -3.238 2.055 leader10 .001 .014 .989 -1.979 2.007 Table 6. Relation between leadership subscales and burnout 26 Standardized t Sig. 95.0% Confidence Interval for B Coefficients Beta Lower Bound (Constant) Upper Bound 4.942 .000 17.803 41.548 emp1 -.268 -1.743 .084 -6.874 .433 emp2 .305 1.837 .048 -.265 7.197 emp3 .257 1.806 .073 -.210 4.643 emp4 -.455 -2.951 .004 -6.690 -1.322 emp5 .108 .912 .363 -1.049 2.845 emp6 -.087 -.743 .459 -3.124 1.417 emp7 .009 .069 .945 -2.513 2.696 emp8 -.193 -1.672 .097 -3.771 .316 emp9 -.072 -.668 .505 -2.443 1.209 emp10 -.103 -.941 .348 -2.806 .997 emp11 .134 1.114 .267 -.806 2.885 emp12 .076 .589 .557 -1.446 2.674 Table 7. Relation between empowerment subscales and burnout 27 Figure 1. Distribution of Scores for the Maslash Burnout Scale 28 Figure 2. linear relation between MBI and leadership scale (predicting burnout through leadership) 29 Figure 3. Linear relation between MBI and empowerment scale (predicting burnout through empowerment) 30