Walter, the one year old RTA cat, with a Vertebral Fracture

advertisement

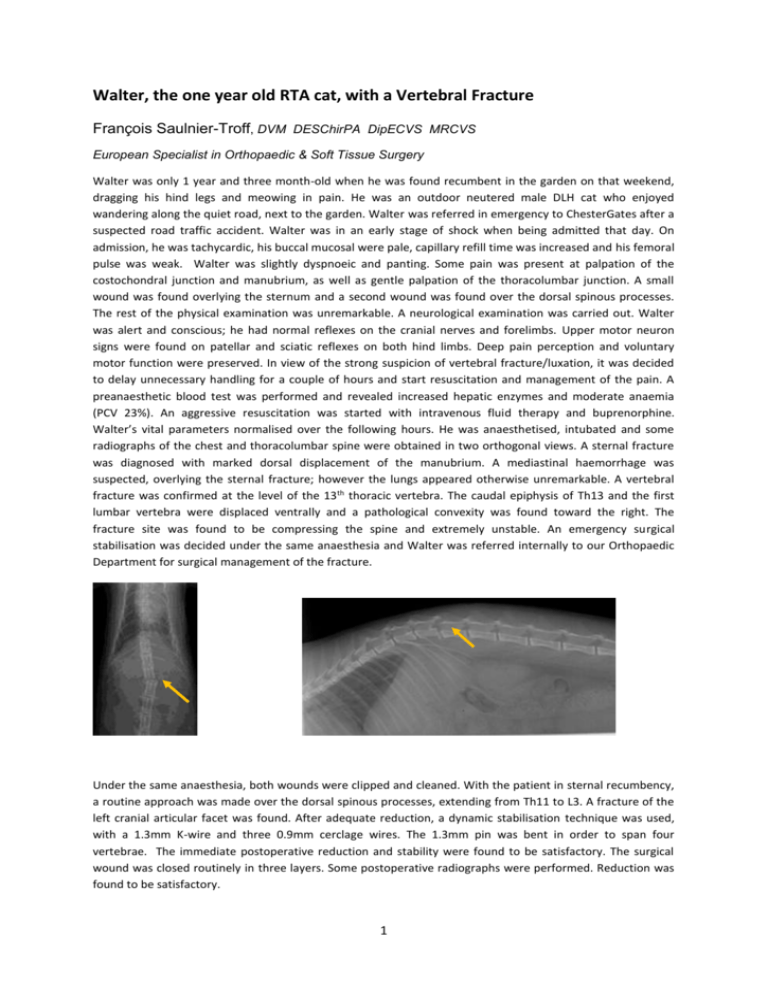

Walter, the one year old RTA cat, with a Vertebral Fracture François Saulnier-Troff, DVM DESChirPA DipECVS MRCVS European Specialist in Orthopaedic & Soft Tissue Surgery Walter was only 1 year and three month-old when he was found recumbent in the garden on that weekend, dragging his hind legs and meowing in pain. He was an outdoor neutered male DLH cat who enjoyed wandering along the quiet road, next to the garden. Walter was referred in emergency to ChesterGates after a suspected road traffic accident. Walter was in an early stage of shock when being admitted that day. On admission, he was tachycardic, his buccal mucosal were pale, capillary refill time was increased and his femoral pulse was weak. Walter was slightly dyspnoeic and panting. Some pain was present at palpation of the costochondral junction and manubrium, as well as gentle palpation of the thoracolumbar junction. A small wound was found overlying the sternum and a second wound was found over the dorsal spinous processes. The rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. A neurological examination was carried out. Walter was alert and conscious; he had normal reflexes on the cranial nerves and forelimbs. Upper motor neuron signs were found on patellar and sciatic reflexes on both hind limbs. Deep pain perception and voluntary motor function were preserved. In view of the strong suspicion of vertebral fracture/luxation, it was decided to delay unnecessary handling for a couple of hours and start resuscitation and management of the pain. A preanaesthetic blood test was performed and revealed increased hepatic enzymes and moderate anaemia (PCV 23%). An aggressive resuscitation was started with intravenous fluid therapy and buprenorphine. Walter’s vital parameters normalised over the following hours. He was anaesthetised, intubated and some radiographs of the chest and thoracolumbar spine were obtained in two orthogonal views. A sternal fracture was diagnosed with marked dorsal displacement of the manubrium. A mediastinal haemorrhage was suspected, overlying the sternal fracture; however the lungs appeared otherwise unremarkable. A vertebral fracture was confirmed at the level of the 13th thoracic vertebra. The caudal epiphysis of Th13 and the first lumbar vertebra were displaced ventrally and a pathological convexity was found toward the right. The fracture site was found to be compressing the spine and extremely unstable. An emergency surgical stabilisation was decided under the same anaesthesia and Walter was referred internally to our Orthopaedic Department for surgical management of the fracture. Under the same anaesthesia, both wounds were clipped and cleaned. With the patient in sternal recumbency, a routine approach was made over the dorsal spinous processes, extending from Th11 to L3. A fracture of the left cranial articular facet was found. After adequate reduction, a dynamic stabilisation technique was used, with a 1.3mm K-wire and three 0.9mm cerclage wires. The 1.3mm pin was bent in order to span four vertebrae. The immediate postoperative reduction and stability were found to be satisfactory. The surgical wound was closed routinely in three layers. Some postoperative radiographs were performed. Reduction was found to be satisfactory. 1 Walter remained hospitalised for ten days for cage rest, pain relief and management of the mediastinal wounds. By the time of the discharge, Walter was able to stand on both hind limbs. He was continent but remained severely ataxic. Both wounds had healed uneventfully. Walter was admitted four weeks later for a repeat neurological examination and some repeat radiographs of the spine. On presentation that day, Walter was able to walk. A mild proprioceptive deficit was still present on both hind limbs and Walter would still have some difficulties on slippery floors. His ambulation was normal on a carpet. Some repeat radiographs were made under sedation that day. These radiographs demonstrated that all our implants were still adequately positioned. The fracture site was stable and adequately reduced and some early callus formation was visible between Th13 and its caudal epiphysis. The diameter of the vertebral canal was preserved. Walter has since then made an uneventful and complete recovery. His proprioception improved over the four following weeks and Walter resumed his happy outdoor cat’s life. Surgical Tips: Vertebral fractures in dogs and cats result most frequently from direct physical trauma. At injury, the spinal cord may be contused or lacerated, which may be followed by sustained compression or distraction if the integrity of the vertebral canal is not quickly restored, with early and adequate reduction/stabilisation. Most of these injuries occur with multiple organ traumas (haemorrhage, shock, airway obstruction, and pneumothorax) and will require preoperative investigation and medical management of the most lifethreatening conditions before any surgical procedure on the spine. Extreme care must be taken to avoid any further spinal injury secondary to patient movement. A thorough neurological examination will be performed. The most important prognostic factor after spinal cord trauma is the presence or absence of deep pain sensation, and therefore, analgesics should not be given 2 prior to this examination. Despite some severe abnormalities on the radiographs, Walter had some decreased voluntary motor function and some intact deep pain sensation prior to surgery. Approximately 20% of the patients with a fracture for less than 24 hours and without deep pain sensation will recover after a spinal surgery. The prognosis after adequate stabilisation is much better if the deep pain sensation was present prior to surgery, as for Walter. Subtle changes in respiratory rate, heart rate or size of the pupils should still be monitored and taken as signs of positive responses when the patient is too debilitated to react. Two orthogonal radiographs will always be required to assess the spinal cord and determine the best surgical option. Misalignment is not always obvious and other projections can be required to demonstrate instability (oblique, stressed, dynamic). Here at ChesterGates, if the deep pain sensation is absent, a preoperative MRI scan could still be performed to assess the severity of the damages to the spine and decide whether surgery is likely to help. Complete return to normal locomotion took three months to Walter. As in this example, animals in which any degree of pain perception is detected with certainty may be expected to be restored to locomotion. 3