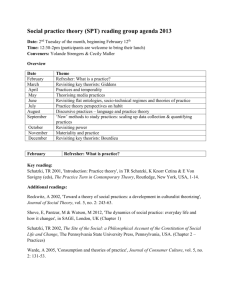

Against consensus. Material, symbolic and discursive struggles

advertisement